Ending Allotment on Indigenous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vrijheid En Veiligheid in Het Politieke Debat Omtrent Vrijheidbeperkende Wetgeving

Stagerapport Vrijheid en Veiligheid in het politieke debat omtrent vrijheidbeperkende wetgeving Jeske Weerheijm Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd in opdracht van Bits of Freedom, in het kader van een stage voor de masteropleiding Cultural History aan de Universiteit Utrecht. De stage is begeleid door Daphne van der Kroft van Bits of Freedom en Joris van Eijnatten van de Universiteit Utrecht. Dit werk is gelicenseerd onder een Creative Commons Naamsvermelding-NietCommercieel- GelijkDelen 4.0 Internationaal licentie. Bezoek http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ om een kopie te zien van de licentie of stuur een brief naar Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. INHOUDSOPGAVE 1. inleiding 1 1.1 vrijheidbeperkende wetgeving 1 1.2 veiligheid en vrijheid 3 1.3 een historische golfbeweging 4 1.4 argumenten 6 1.5 selectiecriteria wetten 7 1.6 bronnen en beperking 7 1.7 stemmingsoverzichten 8 1.8 structuur 8 2. algemene beschouwing 9 2.1 politieke partijen 9 2.2 tijdlijn 17 3. wetten 19 3.1 wet op de Inlichtingen- en veiligheidsdiensten 19 3.2 wet justitiële en strafvorderlijke gegevens 24 3.3 wet eu-rechtshulp – wet vorderen gegevens telecommunicatie 25 3.4 wet computercriminaliteit II 28 3.5 wet opsporing en vervolging terroristische misdrijven 32 3.6 wijziging telecommunicatiewet inzake instellen antenneregister 37 3.7 initiatiefvoorstel-waalkens verbod seks met dieren 39 3.8 wet politiegegevens 39 3.9 wet bewaarplicht telecommunicatiegegevens 44 4. conclusie 50 4.1 verschil tweede en eerste Kamer 50 4.2 politieke -

Carnegie Peacebuilding Conversations Programme

Carnegie Peacebuilding Conversations –Programme Carnegie PeaceBuilding Conversations 24 - 26 September 2018 Programme Monday 24 September 2018 Time Description Location Speakers Organising lead 1:00 – Arrival and registration guests Academy 2:00 pm Building, Peace Palace 2:00 – Word of Welcome Auditorium, Erik de Baedts Carnegie 2:10 pm Peace Palace Director of the Carnegie Foundation - Peace Palace Foundation 2:10 – The Peace Palace: Auditorium, Hugo von Meijenfeldt Carnegie 2:30 pm SDG 16 House Peace Palace SDG Coordinator of The Netherlands, working for of the Ministry of Foundation Foreign Affairs of The Netherlands Dr. Bernard Bot Chairman of the Carnegie Foundation – Peace Palace and Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of The Netherlands Missing Chapter 2:30 – A Children’s Vision on Auditorium, Her Royal Highness Princess Laurentien of The Netherlands Foundation 3:00 pm Peacebuilding Peace Palace Founder of the Missing Chapter Foundation 3:00 – Why are we here: The legacy of Auditorium, Professor David Nasaw Carnegie 3:40 pm Andrew Carnegie in 2018 Peace Palace History Professor at City University of New York Foundation Carnegie Corporation of New York Page 1 of 10 Carnegie Peacebuilding Conversations –Programme 3:40 – Break 4:10 pm 4:10 – Carnegie Institutions Auditorium, High-Level Panel: Carnegie 5:45 pm Worldwide: Peace Palace Foundation Dr. Joel Rosenthal Forging the Future President of the Carnegie Council for Etnics in International Affairs Dr. Eric Isaacs President of the Carnegie Institution for Science Sir John Elvidge -

De Hofvijver Is Een Uitgave Van Hoe Het CDA Anders Tegen De Islam Is Gaan Aankijken

Nieuwsbrief jaargang 1, nummer 8, 31 oktober 2011 'In het diepe...' Agenda Een minister-president krijgt in zijn eerste jaar vaak te maken met nieuwe, november/december 2011, grote en soms zelfs onverwachte problemen en andere tegenvallers. Uit een Den Haag onderzoek van het Parlementair Documentatiecentrum blijkt dat premier Rutte 'Immigratiepolitiek in niet de eerste is die kort na de start van zijn kabinet 'overvallen' wordt met een Nederland en Europa' lastige kwestie: de Eurocrisis. Het blijkt vaker voorgekomen te zijn, zo laat Bert - collegereeks van den Braak op parlement.com zien. 15 november 2011, De Haag Premier Den Uyl kreeg binnen een jaar te maken met de oliecrisis (1973), zijn 'Waar visie ontbreekt, verre voorganger Drees werd geconfronteerd met de Indonesische kwestie komt het volk om' (1948) en premier De Quay liep binnen de kortste keren tegen 'Nieuw-Guinea' - presentatie parlementair aan (1960). Premiers als Marijnen en Cals kregen problemen met het jaarboek koningshuis (Irene, Beatrix & Claus). Het kabinet-Biesheuvel bezweek al in het eerste jaar, net als Balkenende I, de kabinetten-Van Agt tuimelden van het ene 18/19 november 2011, in het andere conflict en als premier had Lubbers de handen vol aan de Groningen sanering van de overheidsfinanciën. 'De voorzitters van de Europese Commissie' 'De wijze waarop 'jonge' premiers die problemen aanpakten, verschilde sterk', - conferentie analyseert Van den Braak. 'Tamelijk nieuwelingen als De Quay en Balkenende Uitgebreide agenda > waren aanvankelijk nog wat onwennig.' Hoewel Rutte al redelijk wat Haagse ervaring had, heeft hij ook te maken met een andere, onbekende risicofactor: de PVV. Cartoon lees verder > Scheepsrecht voor Europa? Plaat van de maand Premier De Quay had het van meet af aan erg moeilijk. -

2017 ECOSOC Forum on Financing for Development Follow-Up

2017 ECOSOC Forum on Financing for Development follow -up Interactive dialogue with intergovernmental bodies of major institutional stakeholders TENTATIVE PROGRAMME Monday, 22 May 2017, 3-6 p.m., Trusteeship Council Chamber, United Nations, New York 3:00 -3:20 p.m. Opening remarks • H.E. Mr. Frederick Musiiwa Makamure Shava, President of ECOSOC (Zimbabwe) • Mr. Herve De Villeroche, Co-Dean of the Board of Executive Directors, World Bank Group • Mr. Hazem Beblawi, Executive Director, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Maldives, Oman, Qatar, Syria, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen, IMF • H.E. Mr. Christopher Onyanga Aparr, President, Trade and Development Board, UNCTAD 3:20 – 5:50 p.m. Interactive discussions Moderator: Ms. Sara Eisen, CNBC 3:20 – 4:35 p.m. Segment 1: Fostering policy coherence in the implementation of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda Remarks by lead discussants (20 minutes) • Mr. Frank Heemskerk, Executive Director, Cyprus, Israel, and Netherlands, World Bank Group • Mr. Daouda Sembene, Chair, Executive Board Committee for Liaison with the World Bank, the United Nations and other International Organizations, IMF • H.E. Mr. Nabeel Munir, Vice President of ECOSOC (Pakistan) Interactive discussions (55 minutes) 4:35 – 5:50 p.m. Segment 2: Inequalities and inclusive growth Remarks by lead discussants (20 minutes) • Ms. Patience Bongiwe Kunene, Executive Director, Angola, Nigeria, and South Africa, World Bank Group • Ms. Nancy Gail Horsman, Executive Directors, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Canada, Dominica, Grenada, Ireland, Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, IMF • Mr. Masaaki Kaizuka, Executive Director, Japan, IMF • H.E. -

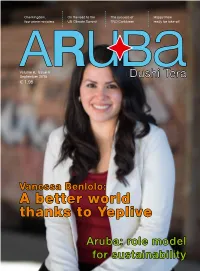

A Better World Thanks to Yeplive

One Kingdom, On the road to the The success of Happy Flow four prime ministers UN Climate Summit TNO Caribbean ready for take-off AVolume 6, Issue 4 R B September 2015 u Dushia Tera 1.95 Vanessa Benlolo: A better world thanks to Yeplive Aruba: role model for sustainability Aruba Dushi Tera is a two-monthly publication for everyone who is interested CONTENTS in the country and people of Aruba. The magazine’s name echoes the opening Sharing best practices 3 lines of Aruba’s national anthem in Papiamento (‘Aruba, Sweet Land’). Working towards a sustainable Aruba 7 Production: ADCaribbean BV TEDxAruba: the world is watching 10 Contributors to this issue: Yeplive makes the world a better place 12 Marjanne Havelaar Myriam Tonk-Croes Rethinking education 14 René Zwart Nico van der Ven Climate: the facts don’t lie 15 Santiago Cortes Elnathan Hijmering Why the Dutch flag waves in the Caribbean 16 Noel Werleman Marko Espinoza The Kingdom: a reliable partner 18 Pedro Diaz Sidney Kock The watchful eye of the Coastguard 22 Tera Group On the road to the UN Climate Summit 24 Translation: Translation Department (AVT), Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs One kingdom, four prime ministers 26 Design and print: The World Bank supports sustainability 28 Schotanus & Jens BV Parlatino: truly inspiring 29 Circulation: 2,500 Sustainability Week 31 All authorial rights reserved. Articles may be reprinted with reference to the source. A test-bed for innovation 33 SUBSCRIBE Dutch maritime tradition chooses Aruba 36 If you would like to receive a copy of Aruba Dushi Tera at your home or work Happy Flow launch 38 address, please email [email protected] ADVERTISE For information about the opportunities and fees for advertising in Aruba Dushi Tera, email: [email protected] Arubahuis R.J. -

Speech from the Throne’ Outlines Plans for the Future

Reports online: www.unitedinternationalpress.com THE NETHERLANDS Queen’s ‘Speech from the Throne’ Outlines Plans for the Future Beatrix Wilhelmina Armgard (born January 31, 1938) has been queen of the Kingdom of the Netherlands since April 1980, when her mother, Queen Juliana, abdicated. As queen, Beatrix has more power than most other reigning monarchs in Europe. While local government is handled by elected offi cials, the queen plays a key role in the country’s international relations and serves as an offi cial spokesperson for the country. The queen gives the ‘Speech from the Throne’ every year in September in an event called ‘Prinsjesdag’, during which she speaks to parliament in the Ridderzaal at the Binnenhof in The Hague. The ‘Speech from the Throne’ sets out the government’s plans for the coming year. In last year’s speech, the queen referred to the global fi nancial crisis and its impact on the Netherlands. She said, “The times we are living in demand determination and a willingness to change. The global fi nancial and economic crisis has hit countries hard, including the Netherlands. The consequences will be felt for a long time to come…. The government's ambition is to turn uncertainty into recovery. The changes required can strengthen the Netherlands economically and socially. We have much to offer our country and one another by standing together and holding fast to the tradition of freedom, responsible citizenship and active European and international engagement.” The queen pointed out that the government had submitted a ‘Crisis and Recovery’ bill aimed at accelerating procedures for infrastructure projects. -

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development International Finance Corporation International Development Association

Page 1 of 2 INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS AND ALTERNATES Executive Director Alternate Appointed by: Shixin CHEN Jiandi YE China Hervé de VILLEROCHÉ Arnaud DELAUNAY France Melanie ROBINSON Clare ROBERTS United Kingdom Masahiro KAN Daiho FUJII Japan Ursula MUELLER Claus HAPPE Germany Matthew MCGUIRE (VACANT) United States Executive Director Alternate Elected by the votes of: Khalid ALKHUDAIRY Turki ALMUTAIRI Saudi Arabia (Saudi Arabia) (Saudi Arabia) Sung-Soo EUN Jason ALLFORD Australia New Zealand (Korea, Republic of) (Australia) Cambodia Palau Kiribati Papua New Guinea Korea, Republic of Samoa Marshall Islands Solomon Islands Micronesia, Federated States of Tuvalu * Mongolia Vanuatu Alejandro FOXLEY Daniel KOSTZER Argentina Paraguay (Chile) (Argentina) Bolivia Peru Chile Uruguay + Jorg FRIEDEN Wieslaw SZCZUKA Azerbaijan Switzerland (Switzerland) (Poland) Kazakhstan Tajikistan Kyrgyz Republic Turkmenistan + Poland Uzbekistán Serbia Subhash Chandra GARG Mohammad TAREQUE Bangladesh India (India) (Bangladesh) Bhutan Sri Lanka Franciscus GODTS Gulsum YAZGANARIKAN Austria Kosovo (Belgium) (Turkey) Belarus + Luxembourg Belgium Slovak Republic Czech Republic Slovenia Hungary Turkey Merza HASAN Karim WISSA Bahrain + Libya (Kuwait) (Egypt, Arab Republic of) Egypt, Arab Republic of Maldives Iraq Oman Jordan Qatar + Kuwait United Arab Emirates Lebanon Yemen, Republic of Frank HEEMSKERK Claudiu DOLTU Armenia Macedonia, former Yugoslav -

1 India-Netherlands Relations General Indo-Dutch Contacts Go

India-Netherlands Relations General Indo-Dutch contacts go back to more than 400 years. Official relations, which were established in 1947, have been cordial and friendly. India's economic growth, its large market, its pool of knowledge workers are of interest to the Netherlands. The main plank of the bilateral ties has been the strong economic and commercial relations. The two countries also share common ideals of democracy, pluralism and the rule of law. Since the early 1980s, the Dutch Government has identified India as an important economic partner. The bilateral relations underwent further intensification after India’s economic liberalization in the early 1990s. In 2006, former Prime Minister Balkenende's Government declared India, along with China and Russia, as priority countries in Dutch foreign policy. Rutte-2, with Frans Timmermans as the Foreign Minister, is committed to continuing the policy of maintaining warm bilateral relations with India. Today, relations between India and the Netherlands have become multifaceted and encompass cooperation in various areas. Political and Economic Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh visited the Netherlands in 2004. The Dutch Prime Minister Mr. Peter Balkenende visited India in January 2006. The second State visit of Queen Beatrix to India took place in 2007. Dutch Foreign Minister Rosenthal visited India in 2011. Other Ministerial level visits from both sides have taken place fairly regularly in the last two years (list of visits is attached at Annex. I). A number of Bilateral Agreements and MOUs have been concluded in diverse areas covering economic and commercial cooperation, culture, science and technology and education (list is attached at Annex. -

Personalization of Political Newspaper Coverage: a Longitudinal Study in the Dutch Context Since 1950

Personalization of political newspaper coverage: a longitudinal study in the Dutch context since 1950 Ellis Aizenberg, Wouter van Atteveldt, Chantal van Son, Franz-Xaver Geiger VU University, Amsterdam This study analyses whether personalization in Dutch political newspaper coverage has increased since 1950. In spite of the assumption that personalization increased over time in The Netherlands, earlier studies on this phenomenon in the Dutch context led to a scattered image. Through automatic and manual content analyses and regression analyses this study shows that personalization did increase in The Netherlands during the last century, the changes toward that increase however, occurred earlier on than expected at first. This study also shows that the focus of reporting on politics is increasingly put on the politician as an individual, the coverage in which these politicians are mentioned however became more substantive and politically relevant. Keywords: Personalization, content analysis, political news coverage, individualization, privatization Introduction When personalization occurs a focus is put on politicians and party leaders as individuals. The context of the news coverage in which they are mentioned becomes more private as their love lives, upbringing, hobbies and characteristics of personal nature seem increasingly thoroughly discussed. An article published in 1984 in the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf forms a good example here, where a horse race betting event, which is attended by several ministers accompanied by their wives and girlfriends is carefully discussed1. Nowadays personalization is a much-discussed phenomenon in the field of political communication. It can simply be seen as: ‘a process in which the political weight of the individual actor in the political process increases 1 Ererondje (17 juli 1984). -

India – Netherlands Relations Since 1947, Indo-Dutch Relations Have

India – Netherlands Relations Since 1947, Indo-Dutch relations have been excellent, marked by strong economic and commercial ties, based on foundation of shared democratic ideals, pluralism, multiculturalism and rule of law. Indo-Dutch relations have been multi-faceted and encompass close cooperation in various areas including political, economy, academics and culture. Since the early 1980s, the Dutch Government has identified India as an important economic partner. The relations underwent further intensification after India’s economic liberalisation in the 1990s with growing recognition of India as an attractive trade and investment partner. In light of convergence of economic and political interests, both countries see value in enhanced dialogue and have constantly striven to strengthen bilateral relations by leveraging each other’s strengths and are currently collaborating in strengthening and expanding the framework of cooperation in various areas like trade and investment, science and technology, information and communication technology, education and culture. There have been periodic high-level exchanges including the visit of Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh to Netherlands in 2004, followed by visits of Dutch Prime Minister Mr. Jan Peter Balkenende in January 2006 and the second State visit of Queen Beatrix to India in 2007. Other visits include:- Visits from Netherlands: November 2007: Foreign Trade Minister Mr. Frank Heemskerk. February 2008: Transport & Water Mgmt Minister Mr. Camiel Eurlings February 2009: Foreign Trade Minister Mr. Frank Heemskerk October 2009: Social Affairs & Employment Minister Mr. Piet H. Donner February, 2011: Mayor of Rotterdam, Mr. A. Aboutaleb April 2011: Infrastructure/Environment Minister Mrs. Melanie Schultz VHaegen. May 2011: Mayor of Amsterdam, Mr. -

Boek Over Totstandkoming Kabinet-Balkenende IV

Het kabinet Balkenende IV werken COALITIEAKKOORD, SAMEN REGERINGSVERKLARING, BEWINDSPERSONEN, FORMATIEVERLOOP samen LE VEN Het kabinet Balkenende IV werken COALITIEAKKOORD, SAMEN REGERINGSVERKLARING, BEWINDSPERSONEN, FORMATIEVERLOOP samen LE VEN ©2007 Rijksvoorlichtingsdienst, Den Haag Foto’s omslag: © RVD Den Haag Vormgeving en druk: Koninklijke De Swart Foto’s: © RVD, ANP: Cynthia Boll (blz. 120), Evert-Jan Daniëls (blz. 110, 13), Rob Keeris (blz. 108), Olaf Kraak (blz. 118), Robin Utrecht (blz. 10) en Robert Vos (blz. 66) Hoewel aan de totstandkoming van deze uitgave de uiterste zorg is besteed, kan voor de aanwezigheid van eventuele (druk)fouten en onvolledigheden niet worden ingestaan en aanvaarden de auteur(s), redacteur(en) en drukker deswege geen aansprakelijkheid voor de gevolgen van eventueel voorkomende fouten en onvolledigheden. While every effort has been made tot ensure the reliability of the information presentend in this publication, Koninklijke De Swart neither guarantees the accuracy of the data contained herein nor accepts responsibility for errors or omissions or their consequences. De officiële documenten behorende bij de kabinetsformatie, zoals Coalitieakkoord, Regeringsverklaring en verslagen van de (in)formateur(s) aan de Koningin, kunt u ook terugvinden via www.regering.nl en www.kabinetsformatie20062007.nl Koninklijke De Swart Thieme GrafiMedia Groep Kobaltstraat 27 Postbus 5318 2505 AD Den Haag Inhoudsopgave Voorwoord 7 Coalitieakkoord 9 Regeringsverklaring 65 CV’s Ministers 77 CV’s Staatssecretarissen 95 Formatieverloop 109 Informatieopdracht Hoekstra 111 Eindverslag Hoekstra 112 Informatieopdracht Wijffels 119 Eindverslag Wijffels 121 Formatieopdracht Balkenende 123 Eindverslag Balkenende 125 Portefeuilles kabinet 128 5 6 Voorwoord ‘Samen werken, samen leven’. Dat is het motto van het kabinet dat op 22 februari 2007 door de Koningin werd beëdigd. -

The Dutch Debate on Enlargement

Communicating Europe Manual: The Netherlands Information and contacts on the Dutch debate on the EU and enlargement to the Western Balkans Supported by the Strategic Programme Fund of the UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office 23 November 2009 www.esiweb.org 2 Communicating Europe: The Netherlands Manual ABOUT THIS MANUAL Who shapes the debate on the future of EU enlargement in The Netherlands today? This manual aims to provide an overview by introducing the key people and key institutions. It starts with a summary of core facts about the Netherlands. It also offers an overview of the policy debates in The Netherlands on the EU, on future enlargement and the Western Balkans. Space is also given to the media landscape; TV, radio and print media and the internet-based media. Any debate in a vibrant democracy is characterised by a range of views. Nonetheless, when it comes to Dutch views on EU enlargement, the people included in this manual are certainly among the most influential. This manual draws on detailed research carried out by ESI from 2005 to 2006 on enlargement fatigue in the Netherlands and on the Dutch debate on Turkey. Fresh research has also been carried out in 2009 especially for the Communicating Europe workshop co-sponsored by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, with the Robert Bosch Stiftung and the European Fund for the Balkans. This text is the sole responsibility of ESI. ESI, Amsterdam, November 2009. www.esiweb.org Communicating Europe: The Netherlands Manual 3 CONTENTS ABOUT THIS MANUAL .................................................................................................................... 2 KEY FACTS ......................................................................................................................................... 5 THE DUTCH POLITICAL PARTIES............................................................................................... 6 DUTCH ATTITUDES TO THE EU - THE 2005 REFERENDUM AND BEYOND .....................