Mizo Hills Revisiting the Early Phase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

Carrying Capacity Analysis in Mizoram Tourism

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January - June 2019), p. 30-37 Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN: 2456-3757 Vol. 04, No. 01 A Journal of Pachhunga University College Jan.-June, 2019 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Open Access https://senhrijournal.ac.in DOI: 10.36110/sjms.2019.04.01.004 CARRYING CAPACITY ANALYSIS IN MIZORAM TOURISM Ghanashyam Deka 1,* & Rintluanga Pachuau2 1Department of Geography, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 2Department of Geography & Resource Management, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Ghanashyam Deka: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5246-9682 ABSTRACT Tourism Carrying Capacity was defined by the World Tourism Organization as the highest number of visitors that may visit a tourist spot at the same time, without causing damage of the natural, economic, environmental, cultural environment and no decline in the class of visitors' happiness. Carrying capacity is a concept that has been extensively applied in tourism and leisure studies since the 1960s, but its appearance can be date back to the 1930s. It may be viewed as an important thought in the eventual emergence of sustainability discussion, it has become less important in recent years as sustainability and its associated concepts have come to dominate planning on the management of tourism and its impacts. But the study of carrying capacity analysis is still an important tool to know the potentiality and future impact in tourism sector. Thus, up to some extent carrying capacity analysis is important study for tourist destinations and states like Mizoram. Mizoram is a small and young state with few thousands of visitors that visit the state every year. -

Letter of Intent for Lease of Cold Storages at Champhai and Vairengte, Mizoram

LETTER OF INTENT FOR LEASE OF COLD STORAGES AT CHAMPHAI AND VAIRENGTE, MIZORAM NLUP IMPLEMENTING BOARD : MIZORAM; AIZAWL ……… 1 TERMS OF REFERENCE (For Lease of Cold Storages) SECTION-I Introduction: Development of Horticulture Sector and its produces is an integral part of NLUP Project highlighted in the Detailed Project Report (DPR) which has been approved by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) of the Government of India. Horticultural crops like Potato, Turmeric, Ginger, Squash, Passion fruit, Spices, M. Oranges, etc., are produced abundantly in the State every harvesting season. There is also a bright scope of market for these crops. The State Government through Agriculture Department and Horticulture Department, built up three Cold Storages at Champhai and Vairengte to preserve Horticultural Crops for further marketing. The State Government has now bestowed the responsibility of the Cold Storages to NLUP Implementing Board right from the implementation of the project till today. SECTION-II Methodology: NLUP Implementing Board, due to limited fund, lack of technical personnel and other infrastructural problems, decided to lease these Plants to capable Firm. According to this, the Firm selected to lease the Plants will debit an Annual Lease Fee to the Govt. of Mizoram during the last month of every financial year. For this, the Firm should know the context and their capacity to run the Cold Storages before making their bid. Specifically the job of the Firm, amongst others, would be as under: To collect harvest from the farmers in general and beneficiaries in particular. To motivate beneficiaries, farmers, etc and their level of confidence about the commitment of their Firm entrusted with lease programme. -

Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project

Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project A preliminary report from the Arakan Rivers Network (ARN) Preliminary Report on the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project November 2009 Copies - 500 Written & Published by Arakan Rivers Network (ARN) P.O Box - 135 Mae Sot Tak - 63110 Thailand Phone: + 66(0)55506618 Emails: [email protected] or [email protected] www.arakanrivers.net Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary …………………………………......................... 1 2. Technical Specifications ………………………………...................... 1 2.1. Development Overview…………………….............................. 1 2.2. Construction Stages…………………….................................... 2 3. Companies and Authorities Involved …………………....................... 3 4. Finance ………………………………………………......................... 3 4.1. Projected Costs........................................................................... 3 4.2. Who will pay? ........................................................................... 4 5. Who will use it? ………………………………………....................... 4 6. Concerns ………………………………………………...................... 4 6.1. Devastation of Local Livelihoods.............................................. 4 6.2. Human rights.............................................................................. 7 6.3. Environmental Damage............................................................. 10 7. India- Burma (Myanmar) Relations...................................................... 19 8. Our Aims and Recommendations to the media................................... -

Article on Experience of My NCC Life Today I Am Going to Share My NCC Life Experience with You

Reg. No. AS18SDA133163 CSUO BISHAL DAS 4th ASSAM BATTALION NCC, KARIMGANJ KARIMGANJ COLLEGE, KARIMGANJ (ASSAM) Pin- 788710 Group SILCHAR NER DIRECTORATE Article on Experience of my NCC life Today I am going to share my NCC life experience with you. I had a dream to serve the country. That's why I want to join the Indian Army. When I passed HS, I first applied for recruitment in the Indian Army. 3rd January 2018 I was my first recruitment then I was physical and medical clear then I was very happy then gave us the date of written examination by recruitment agencie. I and one of my brothers, both, had passed, together, we both started preparing for the written examination. When we went to take the exam, my brother had a C-Certificate of NCC, that is why he did not have to give his written examination and I had to give the exam. When the results came, there was no Mara name in that list, but my brother's name was, My brother got a job in the Indian Army. Then I thought I would also join NCC. Then I reported in which college NCC is very good in our district. I got 4th Assam BN NCC at Karimganj in Karimganj College. Then I first joined the college, and to join the NCC, I approached the unit and told them to talk to the college's ANO. Then I saw the NCC enrollment notice in the college notic board and I contacted them and filed the form for joining NCC.He gave me the date of NCC selection 5th August 2018 I was very pleased. -

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

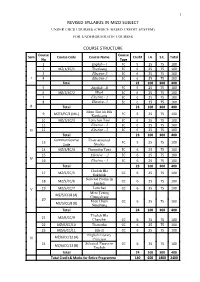

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

Eighth Legislative Assembly of Mizoram (Fourth Session)

1 EIGHTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MIZORAM (FOURTH SESSION) LIST OF BUSINESS FOR FIRST SITTING ON TUESDAY, THE 19th NOVEMBER, 2019 (Time 10:30 A.M. to 1:00 P.M. and 2:00 P.M. to 4:00 P.M.) OBITUARY 1. PU ZORAMTHANGA, hon. Chief Minister to make Obituary reference on the demise of Pu Thankima, former Member of Mizoram Legislative Assembly. QUESTIONS 2. Questions entered in separate list to be asked and oral answers given. ANNOUNCEMENT 3. THE SPEAKER to announce Panel of Chairmen. LAYING OF PAPERS 4. Dr. K. PACHHUNGA, to lay on the Table of the House a copy of Statement of Action Taken on the further recommendation of Committee on Estimates contained in the First Report of 2019 relating to State Investment Programme Management Implementation Unit (SIPMIU) under Urban Development & Poverty Alleviation Department Government of Mizoram. 5. Dr. ZR. THIAMSANGA, to lay on the Table of the House a a copy Statement of Actions Taken by the Government against further recommendations contained in the Third Report, 2019 of Subject Committee-III relating to HIV/AIDS under Health & Family Welfare Department. PRESENTATION OF REPORTS 6. THE SPEAKER to present to the House the Third Report of Business Advisory Committee. 7. PU LALDUHOMA to present to the House the following Reports of Public Accounts Committee : 2 i) First Report on the Report of Comptroller & Auditor General of India for the year 2011-12, 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15 and 2015-16 relating to Taxation Department. ii) Second Report on the Report of Comptroller & Auditor General of India for the year 2014-15 and 2015-16 relating to Food, Civil Supplies and Consumer Affairs Department. -

Notable Bird Records from Mizoram in North-East India (Forktail 22: 152-155)

152 SHORT NOTES Forktail 22 (2006) Notable bird records from Mizoram in north-east India ANWARUDDIN CHOUDHURY The state of Mizoram (21°58′–24°30′N 92°16′–93°25′E) northern Mizoram, in March 1986 (five days), February is located in the southern part of north-east India (Fig. 1). 1987 (seven days) and April 1988 (5 days) while based in Formerly referred to as the Lushai Hills of southern Assam, southern Assam. During 2–17 April 2000, I visited parts it covers an area of 21,081 km2. Mizoram falls in the Indo- of Aizawl, Kolasib, Lawngtlai, Lunglei, Mamit, Saiha, Burma global biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000) and Serchhip districts and surveyed Dampa Sanctuary and the Eastern Himalaya Endemic Bird Area and Tiger Reserve, Ngengpui Willdlife Sanctuary, (Stattersfield et al. 1998). The entire state is hilly and Phawngpui National Park and the fringe of Khawnglung mountainous. The highest ranges are towards east with Wildlife Sanctuary. This included 61 km of foot transect the peaks of Phawngpui (2,157 m; the highest point in along paths and streams, 2.5 km of boat transects along Mizoram) and Lengteng (2,141 m). The lowest elevation, the Ngengpui River and Palak Dil, and 1,847 km of road <100 m, is in the riverbeds near the borders with Assam transects. During 15–22 February 2001, I visited parts of and Bangladesh border. The climate is tropical monsoon- type with a hot wet summer and a cool dry winter. Table 1. Details of sites mentioned in the text. Temperatures range from 7° to 34°C; annual rainfall ranges from 2,000 to 4,000 mm. -

Synod 2017 Bulletin 3

INKHAWMPUI VAWI 94-NA December 5 - 10, 2017 Bungkawn Pastor Bial : Bungkawn Kohhran Biak In INKHAWMPUI CHANCHINBU CHHUAH THUMNA DECEMBER 10, 2017 (PATHIANNI) LAWMTHU SAWINA SYNOD INKHAWMPUI VAWI 94-NA Synod Vawi 94-na chu tluang takin kan TLUANG TAKA HMAN MEK ZEL A NI lo zo dawn ta a. Inkhawmpui tluang taka min hruaitu Pathian hnenah te, Bungkawn Synod Inkhawmpui Vawi 94-na chu tluang taka hman mek zel a ni. A thlengtu Pastor Bial chhunga Kohhran hrang Bungkawn Pastor Bialin nghakhlel taka kan lo thlir chu a bul kan tan dawn chauh hrangte chungah te, Sub-Committtee emaw kan tih laiin zaninah a lo tiak dawn ta reng mai. Hei hi Palai zawng zawngte hrang hrangte chungah leh mimal chanvo kan mangthana che u ni nghal mai se, mahni khua leh veng lam kan pan hunah dam neitu kohhran member-te chungah taka in haw a, tluang taka rawng in bawl zel theih nan duhsakna sang ber kan hlan a lawmthu kan sawi a. Synod Inkhawmpui che u. Tin, 2018 Synod Inkhawmpui Electric Veng Biak Ina neih tur atan Electric kan thlenna kawnga kan mamawh phal Veng Pastor Bial pawh duhsakna sang ber kan hlan nghal bawk a ni. taka min hmantirtu hrang hrangte hnenah Inkhawmpui rorel tluang taka neih chu dar 1:30 ah tan a ni dawn a. lawmthu kan sawi bawk a, chungte chu - niin nimin, Inrinni khan rorel zawh hman Chawhnu inkhawmah Lalpa Zanriah 1) Mizoram State Sports Council a nih loh avangin nizan inkhawm ban Sakramen kilho a ni ang a. He hunah - Mattress 100 nos. -

World Bank Document

MIZORAM HEALTH SYSTEMS Public Disclosure Authorized STRENGTHENING PROJECT (P173958) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Draft Report Public Disclosure Authorized November 2020 Table of Content Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. vi Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Environmental Profile of Mizoram ...................................................................................................... 1 Socio-Cultural and Demographic Profile of Mizoram ......................................................................... 3 Demographic Profile ....................................................................................................................... 3 Tribes of Mizoram ........................................................................................................................... 4 Autonomous District Councils in Mizoram ......................................................................................... 4 Protected Areas .................................................................................................................................. 4 Health Status -

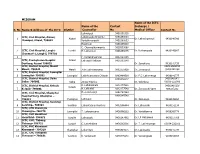

MIZORAM S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Name Of

MIZORAM Name of the ICTC Name of the Contact Incharge / S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Counsellor No Medical Officer Contact No Lalhriatpuii 9436192315 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Aizawl, Lalbiakzuala Khiangte 9856450813 1 Aizawl Dr. Lalhmingmawii 9436140396 Dawrpui, Aizawl, 796001 Vanlalhmangaihi 9436380833 Hauhnuni 9436199610 C. Chawngthanmawia 9615593068 2 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Lunglei Lunglei H. Lalnunpuii 9436159875 Dr. Rothangpuia 9436146067 Chanmari-1, Lunglei, 796701 3 F. Vanlalchhanhimi 9612323306 ICTC, Presbyterian Hospital Aizawl Lalrozuali Rokhum 9436383340 Durtlang, Aizawl 796025 Dr. Sanghluna 9436141739 ICTC, District Hospital, Mamit 0389-2565393 4 Mamit- 796441 Mamit John Lalmuanawma 9862355928 Dr. Zosangpuii /9436141094 ICTC, District Hospital, Lawngtlai 5 Lawngtlai- 796891 Lawngtlai Lalchhuanvawra Chinzah 9863464519 Dr. P.C. Lalramenga 9436141777 ICTC, District Hospital, Saiha 9436378247 9436148247/ 6 Saiha- 796901 Saiha Zingia Hlychho Dr. Vabeilysa 03835-222006 ICTC, District Hospital, Kolasib R. Lalhmunliani 9612177649 9436141929/ Kolasib 7 Kolasib- 796081 H. Lalthafeli 9612177548 Dr. Zorinsangi Varte 986387282 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Champhai H. Zonunsangi 9862787484 Hospital Veng, Champhai – 9436145548 8 796321 Champhai Lalhlupuii Dr. Zatluanga 9436145254 ICTC, District Hospital, Serchhip 9 Serchhip– 796181 Serchhip Lalnuntluangi Renthlei 9863398484 Dr. Lalbiakdiki 9436151136 ICTC, CHC Chawngte 10 Chawngte– 796770 Lawngtlai T. Lalengmuana 9436966222 Dr. Vanlallawma 9436360778 ICTC, CHC Hnahthial 11 Hnahthial– 796571