Counter-Insurgency and Modes of Disciplining in Northeast India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carrying Capacity Analysis in Mizoram Tourism

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January - June 2019), p. 30-37 Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN: 2456-3757 Vol. 04, No. 01 A Journal of Pachhunga University College Jan.-June, 2019 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Open Access https://senhrijournal.ac.in DOI: 10.36110/sjms.2019.04.01.004 CARRYING CAPACITY ANALYSIS IN MIZORAM TOURISM Ghanashyam Deka 1,* & Rintluanga Pachuau2 1Department of Geography, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 2Department of Geography & Resource Management, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Ghanashyam Deka: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5246-9682 ABSTRACT Tourism Carrying Capacity was defined by the World Tourism Organization as the highest number of visitors that may visit a tourist spot at the same time, without causing damage of the natural, economic, environmental, cultural environment and no decline in the class of visitors' happiness. Carrying capacity is a concept that has been extensively applied in tourism and leisure studies since the 1960s, but its appearance can be date back to the 1930s. It may be viewed as an important thought in the eventual emergence of sustainability discussion, it has become less important in recent years as sustainability and its associated concepts have come to dominate planning on the management of tourism and its impacts. But the study of carrying capacity analysis is still an important tool to know the potentiality and future impact in tourism sector. Thus, up to some extent carrying capacity analysis is important study for tourist destinations and states like Mizoram. Mizoram is a small and young state with few thousands of visitors that visit the state every year. -

Letter of Intent for Lease of Cold Storages at Champhai and Vairengte, Mizoram

LETTER OF INTENT FOR LEASE OF COLD STORAGES AT CHAMPHAI AND VAIRENGTE, MIZORAM NLUP IMPLEMENTING BOARD : MIZORAM; AIZAWL ……… 1 TERMS OF REFERENCE (For Lease of Cold Storages) SECTION-I Introduction: Development of Horticulture Sector and its produces is an integral part of NLUP Project highlighted in the Detailed Project Report (DPR) which has been approved by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) of the Government of India. Horticultural crops like Potato, Turmeric, Ginger, Squash, Passion fruit, Spices, M. Oranges, etc., are produced abundantly in the State every harvesting season. There is also a bright scope of market for these crops. The State Government through Agriculture Department and Horticulture Department, built up three Cold Storages at Champhai and Vairengte to preserve Horticultural Crops for further marketing. The State Government has now bestowed the responsibility of the Cold Storages to NLUP Implementing Board right from the implementation of the project till today. SECTION-II Methodology: NLUP Implementing Board, due to limited fund, lack of technical personnel and other infrastructural problems, decided to lease these Plants to capable Firm. According to this, the Firm selected to lease the Plants will debit an Annual Lease Fee to the Govt. of Mizoram during the last month of every financial year. For this, the Firm should know the context and their capacity to run the Cold Storages before making their bid. Specifically the job of the Firm, amongst others, would be as under: To collect harvest from the farmers in general and beneficiaries in particular. To motivate beneficiaries, farmers, etc and their level of confidence about the commitment of their Firm entrusted with lease programme. -

Notable Bird Records from Mizoram in North-East India (Forktail 22: 152-155)

152 SHORT NOTES Forktail 22 (2006) Notable bird records from Mizoram in north-east India ANWARUDDIN CHOUDHURY The state of Mizoram (21°58′–24°30′N 92°16′–93°25′E) northern Mizoram, in March 1986 (five days), February is located in the southern part of north-east India (Fig. 1). 1987 (seven days) and April 1988 (5 days) while based in Formerly referred to as the Lushai Hills of southern Assam, southern Assam. During 2–17 April 2000, I visited parts it covers an area of 21,081 km2. Mizoram falls in the Indo- of Aizawl, Kolasib, Lawngtlai, Lunglei, Mamit, Saiha, Burma global biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000) and Serchhip districts and surveyed Dampa Sanctuary and the Eastern Himalaya Endemic Bird Area and Tiger Reserve, Ngengpui Willdlife Sanctuary, (Stattersfield et al. 1998). The entire state is hilly and Phawngpui National Park and the fringe of Khawnglung mountainous. The highest ranges are towards east with Wildlife Sanctuary. This included 61 km of foot transect the peaks of Phawngpui (2,157 m; the highest point in along paths and streams, 2.5 km of boat transects along Mizoram) and Lengteng (2,141 m). The lowest elevation, the Ngengpui River and Palak Dil, and 1,847 km of road <100 m, is in the riverbeds near the borders with Assam transects. During 15–22 February 2001, I visited parts of and Bangladesh border. The climate is tropical monsoon- type with a hot wet summer and a cool dry winter. Table 1. Details of sites mentioned in the text. Temperatures range from 7° to 34°C; annual rainfall ranges from 2,000 to 4,000 mm. -

World Bank Document

MIZORAM HEALTH SYSTEMS Public Disclosure Authorized STRENGTHENING PROJECT (P173958) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Draft Report Public Disclosure Authorized November 2020 Table of Content Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. vi Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Environmental Profile of Mizoram ...................................................................................................... 1 Socio-Cultural and Demographic Profile of Mizoram ......................................................................... 3 Demographic Profile ....................................................................................................................... 3 Tribes of Mizoram ........................................................................................................................... 4 Autonomous District Councils in Mizoram ......................................................................................... 4 Protected Areas .................................................................................................................................. 4 Health Status -

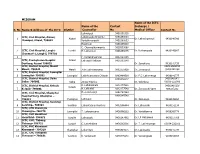

MIZORAM S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Name Of

MIZORAM Name of the ICTC Name of the Contact Incharge / S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Counsellor No Medical Officer Contact No Lalhriatpuii 9436192315 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Aizawl, Lalbiakzuala Khiangte 9856450813 1 Aizawl Dr. Lalhmingmawii 9436140396 Dawrpui, Aizawl, 796001 Vanlalhmangaihi 9436380833 Hauhnuni 9436199610 C. Chawngthanmawia 9615593068 2 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Lunglei Lunglei H. Lalnunpuii 9436159875 Dr. Rothangpuia 9436146067 Chanmari-1, Lunglei, 796701 3 F. Vanlalchhanhimi 9612323306 ICTC, Presbyterian Hospital Aizawl Lalrozuali Rokhum 9436383340 Durtlang, Aizawl 796025 Dr. Sanghluna 9436141739 ICTC, District Hospital, Mamit 0389-2565393 4 Mamit- 796441 Mamit John Lalmuanawma 9862355928 Dr. Zosangpuii /9436141094 ICTC, District Hospital, Lawngtlai 5 Lawngtlai- 796891 Lawngtlai Lalchhuanvawra Chinzah 9863464519 Dr. P.C. Lalramenga 9436141777 ICTC, District Hospital, Saiha 9436378247 9436148247/ 6 Saiha- 796901 Saiha Zingia Hlychho Dr. Vabeilysa 03835-222006 ICTC, District Hospital, Kolasib R. Lalhmunliani 9612177649 9436141929/ Kolasib 7 Kolasib- 796081 H. Lalthafeli 9612177548 Dr. Zorinsangi Varte 986387282 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Champhai H. Zonunsangi 9862787484 Hospital Veng, Champhai – 9436145548 8 796321 Champhai Lalhlupuii Dr. Zatluanga 9436145254 ICTC, District Hospital, Serchhip 9 Serchhip– 796181 Serchhip Lalnuntluangi Renthlei 9863398484 Dr. Lalbiakdiki 9436151136 ICTC, CHC Chawngte 10 Chawngte– 796770 Lawngtlai T. Lalengmuana 9436966222 Dr. Vanlallawma 9436360778 ICTC, CHC Hnahthial 11 Hnahthial– 796571 -

District Census Handbook, Mamit, Part a & B, Series-16, Mizoram

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES.. 16 MIZORAM DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Part - A & B MAMIT DISTRICT VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT P.K. Bhattacharjee of the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations, Mizoram Sanga Pa Thelret at Oampui Ngaw, Mamit Along the National Highway No. 44 between Dampui and Mamit District Hqtrs. lies a vast span of thick forest known as 'Dampui Ngaw"" which is the abode of different kinds of wildlife, countless varieties of flowers and rare orchids. Fore those who come to Mami~ the sweet melody ofthe singing bird and the humming insects along this cool virgin forest linger on for years together. Deep down in the middle of the forest and more than 1 km. away from the main road, stands a famous rubber tree known as ' Sanga Pa Thelret' which is . believed to have been planted at the tum of the 20th Century by a bereaved father 'Sanga Pa' , a villager of Zotlang ThinglubuI, in memory of his beloved one who passed away. The old magnificient trunk produces its brunches in all directions and every branch produces a number of branches downward which take roots on the gronnd and act as supporters to the main branches. The towering tree has not stopped growing and its ever widening branches now covers almost an acre of land. Few kilometers away from this Dampui Ngaw, largest wildlife sanctualy known as Dampa Sanctuary covering an overall area of 681 sq. km. had been set up. A variety of wildlife like Tiger, Elephant, Leopard, Bear, Deer, Sombre, Serow, Wlldpigs and a variety of birds are now enjoying sanctuary protection in this Dampa Tiger Forest Reserve. -

Political Turmoil in Mizoram

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Political Turmoil in Mizoram Resolving the Hmar Question ROLUAHPUIA Vol. 50, Issue No. 31, 01 Aug, 2015 Roluahpuia ([email protected]) is a doctoral candidate at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Guwahati, Assam. The seemingly intractable Hmar question in Mizoram has erupted again with the resuming of violent clashes between HPC (D) and the state government. Sporadic violence is becoming the norm in the state with the latest being the killing of three policemen by the Hmar militant outfits. Rather than looking at the logic of the struggle, the state government prefers to reply to such dissent through the use of force. On 29 March 2015, the convoy of three members of legislative assembly (MLAs) of Mizoram was ambushed by suspected militants belonging to Hmar People’s Convention (Democratic) [HPC (D)] in which three policemen lost their lives. The ambush took place in the northern part of Mizoram bordering Manipur, mostly inhabited by the Hmar tribe. HPC (D) is reported to have active operations in this part of the state. It is here that several outfits are demanding for separate autonomous councils for the Hmar tribe within the state of Mizoram. In short, it is the imagined territorial homeland which the HPC (D) refers to as “Sinlung.” The death of three policemen has caused wide uproar and resentment from the people of Mizoram. The ruling Congress government sent out a strong message to the outfit without delay and has promised to take stringent moves to counter such violent acts. The chief minister of the state, Lalthanhawla, stated that the Mizoram government had accepted the challenge of the HPC (D) and would respond to it. -

KOLASIB DISTRICT Inventory of Agriculture 2015

KOLASIB DISTRICT Inventory of Agriculture 2015 KOLASIB DISTRICT Inventory of Agriculture 2015 ICAR-ATARI-III, Umiam Page 2 Correct Citation: Bhalerao A.K., Kumar B., Singha A. K., Jat P.C., Bordoloi, R., Deka Bidyut C., 2015, Kolasib district inventory of Agriculture, ICAR-Agricultural Technology Application Research Institute, Umiam, Meghalaya, India Published by: The Director, ICAR-Agricultural Technology Application Research Institute, Umiam (Barapani), Meghalaya-793103 Email: [email protected] Website: http://icarzcu3.gov.in Phone no. 0364-2570081 Compiled By: Lalramengi, SMS (Agronomy) P.C.Lalrintluanga, SMS (Horticulture) C.Lalfakawma, SMS (Plant Prottection) Dr. Rebecca Lalmuanpuii, SMS (Agro- Dr. David Malsawmdawngliana, SMS Lallawmzuala, Programme Assistant (Computer) Edited by: Amol K. Bhalarao, Scientist (AE) Bagish Kumar, Scientist (AE) A. K. Singha, Pr. Scientist (AE) P. C. Jat, Sr. Scientist (Agro) R. Bordoloi, Pr. Scientist (AE)\ Bidyut C. Deka, Director, ATARI Umiam Contact: The Director of Agriculture Directorate of Agriculture (Research & Education) Government of Mizoram Aizawl, Mizoram Pin: 796001 Telephone Number: (03837) 220360 Mobile Number: 9436152440 Website: kvkkolasib.mizoram.gov.in Word Processing: Synshai Jana Cover Design: Johannes Wahlang Layout and Printing: Technical Cell, ICAR-ATARI, Umiam ICAR-ATARI-III, Umiam Page 3 FOREWORD The ICAR-Agricultural Technology Application Research institute, Zone-III with its headquarters at Umiam, Meghalaya is primarily responsible for monitoring and reviewing of technology -

Colonialism in Northeast India: an Environmental History of Forest Conflict in the Frontier of Lushai Hills 1850-1900

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 4 Issue 1 ǁ January. 2015 ǁ PP.67-75 Colonialism in Northeast India: An Environmental History of Forest Conflict in the Frontier of Lushai Hills 1850-1900 Robert Lalremtluanga Ralte Research Scholar, Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University ABSTRACT: The present study would deals with the interaction between the colonialist and the Mizos in the frontier areas of Lushai Hills. At a larger context, historical enquiry in this study is largely divided into two part viz., pre-colonial Mizo society and the intervention of colonial power. As anthropological studies show, there is an interesting connection between belief systems of the traditional societies and their knowledge of and attitude to the environment. In this sense, the proposed study would attempt to understand how the belief system of Mizo society shaped their attitude to the environment. An attempt will be made to understand the various knowledge systems of Mizo society before the intrusion of ‘colonial modernity’ in the region. On the other hand, the study also tries to understand how the ‘traditional knowledge’ of Mizo society had been structured by colonialism. Accordingly, the present study would try to substantiate how the colonial knowledge system, based on modern scientific rationality, perceived and transformed the traditional knowledge system and practices. Thus, it is an attempt to unpack the interaction between the two groups by studying forest conflict in the frontier which cover the period roughly from 1850 to1900. KEYWORDS: colonialism, frontier, forest, land, traditional, conflict, relation, intervention, community. -

Directorate of Information & Public Relations

DIRECTORATE OF INFORMATION & PUBLIC RELATIONS Government of Mizoram Page Links: https://dipr.mizoram.gov.in/post/daily-situation-report-on-covid-19-quarantine-facilitation-centre-kolasib-district-report-as-on- 090520201589123102p DAILY SITUATION REPORT ON COVID-19 QUARANTINE FACILITATION CENTRE KOLASIB DISTRICT REPORT AS ON 09.05.2020 No.962/2020-2021 Cumulative No. Inmates Admitted - 458 Cumulative No. of Inmates Released - 309 Cumulative No. of Inmates Released - 0 Total No of Inmates presently staying in Facilitation Centre - 149 No. of No. of No. of Facilitation Suspected Case Date Time Inmates Inmates Centre referred to Admitted Released Isolation Ward 9:00 pm - 12:00 0 0 0 noon SIRD Hostel, 12:00 noon-5:00pm 0 0 0 09.05.2020 Kolasib 12:00 noon-5:00pm 0 0 0 Total 0 0 0 Cumulative Report 14 14 0 No. of No. of No. of Facilitation Suspected Case Date Time Inmates Inmates Centre referred to Admitted Released Isolation Ward 9:00 pm - 12:00 0 0 0 noon Tourist Lodge 12:00 noon-5:00pm 0 0 0 09.05.2020 Kolasib 5:00pm - 9:00 pm 0 1 0 Total 0 1 0 Cumulative Report 75 42 0 No. of No. of No. of Facilitation Suspected Case Date Time Inmates Inmates Centre referred to Admitted Released Isolation Ward 9:00 pm - 12:00 0 0 0 noon DIET Hostel, 12:00 noon-5:00pm 0 0 0 09.05.2020 Kolasib 5:00pm - 9:00 pm 0 0 0 Total 0 0 0 Cumulative Report 31 18 0 No. -

Mizoram: Laboratory Mapping Human Samples Testing Labs, Mizoram

Mizoram: Laboratory Mapping Human Samples Testing Labs, Mizoram Name of the Testing facility: Culture test/ELISA/Rapid Lab/Facility(Lab Postal Address of the Sl. No. Name of Nodal Person Email ID of the Nodal Person Test/Molecular testing, etc categorization: Lab Human) Sakardai CHC, Sakawrdai CHC [email protected] Rapid Test/ 1 Sakawrdai, Dr. H.K. Lalruatfela Laboratory,Aizawl East [email protected] Molecular Test Pin : 796111 Darlawn PHC, Darlawn PHC Rapid Test/ 2 Darlawn, Dr. C. Vanlalremsiama [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East Molecular Test Pin : 796111 Khawruhlian PHC, Khawruhlian PHC Rapid Test/ 3 Khawruhlian. Dr. Shahnaz Zothanzami [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East Molecular Test Pin : 7960017 Suangpuilawn PHC, Suangpuilawn PHC [email protected] Rapid Test/ 4 Suangpuilawn, Dr. Isaac Lalrawngbawla Laboratory,Aizawl East [email protected] Molecular Test Pin : 796261 Phullen PHC Phullen PHC, Phullen, Rapid Test/ 5 Dr. Vanhmingliani Khiangte [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East Pin : 796261 Molecular Test Phuaibuang PHC, Phuaibuang PHC Phuaibuang, 6 Dr. B. Lalramhluna [email protected] Rapid Test Laboratory,Aizawl East Pin : 796261 P.O. : Saitual Thingsulthliah CHC, Thingsulthliah CHC Rapid Test/ 7 Thingsulthliah, Dr. Lalrinkimi Khiangte [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East Molecular Test Pin : 796161 Saitual CHC, Saitual CHC Rapid Test/ 8 Saitual, Dr. Lucy Lalsangpuii [email protected] Laboratory,Aizawl East, Molecular Test Pin : 796121 ITI UPHC, ITI ITI UHC Laboratory,Aizawl 9 Aizawl : Mizoram. Dr. Lalnunzira [email protected] Rapid Test East Pin : 796005 Zemabawk UPHC, Zemabawk, Zemabawk UHC Near Zemabawk Rapid Test/ 10 Dr. Lalbiaksangi Royte [email protected] Laboratory,,Aizawl East Thlanmual Molecular Test Aizawl : Mizoram Pin : 796017 Name of the Testing facility: Culture test/ELISA/Rapid Lab/Facility(Lab Postal Address of the Sl. -

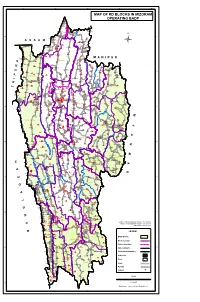

Map of Rd Blocks in Mizoram Operating Badp

92°20'0"E 92°40'0"E 93°60'0"E 93°20'0"E 93°40'0"E MAP OF RD BLOCKS IN MIZORAM Vairengte II OPERATING BADP Vairengte I Saihapui (V) Phainuam Chite Vakultui Saiphai Zokhawthiang North Chhimluang North Chawnpui Saipum Mauchar Phaisen Bilkhawthlir N 24°20'0"N 24°20'0"N Buhchang Bilkhawthlir S Chemphai North Thinglian Bukvannei I Tinghmun BuBkvIaLnKneHi IAI WTHLIR Parsenchhip Saihapui (K) Palsang Zohmun Builum Sakawrdai(Upper) Thinghlun(Lushaicherra) Hmaibiala Veng Rengtekawn Kanhmun South Chhimluang North Hlimen Khawpuar Lower Sakawrdai Luimawi KOLASIB N.Khawdungsei Vaitin Pangbalkawn Hriphaw Luakchhuah Thingsat Vervek E.Damdiai Bungthuam Bairabi New_Vervek Meidum North Thingdawl Thingthelh Lungsum Borai Saikhawthlir Rastali Dilzau H Thuampui(Zawlnuam) Suarhliap R Vengpuh i(Zawlnuam) i Chuhvel Sethawn a k DARLAWN g THINGDAWL Ratu n a Zamuang Kananthar L Bualpui Bukpui Zawlpui Damdiai Sunhluchhip Lungmawi Rengdil N.Khawlek Hortoki Sailutar Sihthiang R North Kawnpui I i R Daido a Vawngawnzo l Vanbawng v i Tlangkhang Kawnpui w u a T T v Mualvum North Chaltlang N.Serzawl i u u Chiahpui i N.E.Tlangnuam Khawkawn s T Darlawn a 24°60'0"N 24°60'0"N Lamherh R Kawrthah Khawlian Mimbung K Sarali North Sabual Sawleng Chilui Zanlawn N.E.Khawdungsei Saitlaw ZAWLNUAM Lungmuat Hrianghmun SuangpuilaPwnHULLEN Vengthar Tumpanglui Teikhang Venghlun Chhanchhuahna kepran Khamrang Tuidam Bazar Veng Nisapui MAMIT Phaizau Phuaibuang Liandophai(Bawngva) E.Phaileng Serkhan Luangpawn Mualkhang Darlak West Serzawl Pehlawn Zawngin Sotapa veng Sentlang T l Ngopa a Lungdai