Daimler AG, Formerly Known As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) Coding Summary (Internal Use Only)

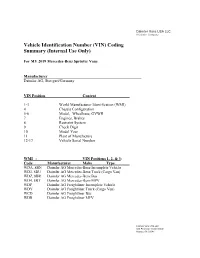

Daimler Vans USA LLC A Daimler Company Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) Coding Summary (Internal Use Only) For MY 2019 Mercedes-Benz Sprinter Vans Manufacturer Daimler AG, Stuttgart/Germany VIN Position Content 1-3 World Manufacturer Identification (WMI) 4 Chassis Configuration 5-6 Model, Wheelbase, GVWR 7 Engines, Brakes 8 Restraint System 9 Check Digit 10 Model Year 11 Plant of Manufacture 12-17 Vehicle Serial Number WMI - VIN Positions 1, 2, & 3: Code Manufacturer Make Type WDA, 8BN Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz Incomplete Vehicle WD3, 8BU Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz Truck (Cargo Van) WDZ, 8BR Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz Bus WD4, 8BT Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz MPV WDP Daimler AG Freightliner Incomplete Vehicle WDY Daimler AG Freightliner Truck (Cargo Van) WCD Daimler AG Freightliner Bus WDR Daimler AG Freightliner MPV Daimler Vans USA LLC 303 Perimeter Center North Atlanta, GA 30346 Daimler Vans USA LLC A Daimler Company Chassis Configuration - VIN Position 4: Code Chassis Configuration / Intended Market P All 4x2 Vehicle Types / U.S. B All 4x2 Vehicle Types / Canada F All 4x4 Vehicle Types / U.S. C All 4x4 Vehicle Types / Canada Model, Wheelbase, GVWR - VIN Positions 5 & 6: Code Model Wheelbase GVWR E7 C1500/C2500/P1500 3665 mm/ 144 in. 8,000 lbs. to 9,000 lbs. Class G E8 C2500/P2500 4325 mm/ 170 in. 8,000 lbs. to 9,000 lbs. Class G F0 C2500/C3500 3665 mm/ 144 in. 9,000 lbs. to 10,000 lbs. Class H F1 C2500/C3500 4325 mm/ 170 in. 9,000 lbs. to 10,000 lbs. Class H F3 C4500/C3500 3665 mm/ 144 in. -

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

Case: 15-1914 Document: 48 Page: 1 Filed: 12/21/2015 2015-1914, -1919 United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ALTERA CORPORATION, XILINX, INC., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. PAPST LICENSING GMBH & CO. KG, Defendant-Appellee. Appeals from the United States District Court for the Northern District of California in Case Nos. 5:14-cv-04794-LHK and 5:14-cv-04963-LHK, Judge Lucy H. Koh BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE AO KASPERSKY LAB, LIMELIGHT NETWORKS, INC., QVC, INC., SAS INSTITUTE INC., SYMMETRY LLC, AND VIZIO, INC. IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT XILINX, INC. STEVEN D. MOORE DARIUS SAMEROTTE KILPATRICK TOWNSEND & STOCKTON LLP Eighth Floor, Two Embarcadero Center San Francisco, CA 94111 Telephone: 415 576 0200 Attorneys for AMICI CURIAE DECEMBER 21, 2015 COUNSEL PRESS, LLC (888) 277-3259 Case: 15-1914 Document: 48 Page: 2 Filed: 12/21/2015 CERTIFICATE OF INTEREST Counsel for amici certifies the following: 1. The full name of every party or amicus represented by me is: AO Kaspersky Lab, Limelight Networks, Inc., QVC, Inc., SAS Institute Inc., Symmetry LLC, and VIZIO, Inc. 2. The name of the real party in interest represented by us is: N/A 3. All parent corporations and any public companies that own 10 percent or more of the stock of the parties represented by me are: AO Kaspersky Lab is a wholly owned subsidiary of Kaspersky Lab Ltd. Investment entities affiliated with Goldman, Sachs & Co. own over 10 percent of Limelight Networks, Inc. QVC is a wholly owned subsidiary of Liberty Interactive Corporation. SAS Institute Inc. and Symmetry LLC have no parent corporations, and there are no public companies that own 10% or more of them. -

European Commission

C 268/18 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union 14.8.2020 PROCEDURES RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY EUROPEAN COMMISSION Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9572 – BMW/Daimler/Ford/Porsche/Hyundai/Kia/IONITY) Candidate case for simplified procedure (Text with EEA relevance) (2020/C 268/06) 1. On 7 August 2020, the Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (1). This notification concerns the following undertakings: — BMW AG (‘BMW’, Germany), — Daimler AG (‘Daimler’, Germany), — Ford Motor Company (‘Ford’, USA), — Dr Ing. h.c. F. Porsche Aktiengesellschaft (‘Porsche’, Germany). Porsche is part of the Volkswagen Group, — Hyundai Motor Company (‘Hyundai’, South Korea), which indirectly controls Kia Motor Corporation (‘Kia’, South Korea). Hyundai and Kia (together ‘Hyundai’) both belong to the Hyundai Motor Group (South Korea). BMW, Daimler, Ford, Porsche and Hyundai acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) and Article 3(4) of the Merger Regulation joint control of the whole of IONITY Holding GmbH & Co. KG (‘IONITY’, Germany), a full function joint venture established in 2017 by BMW, Daimler, Ford and Porsche. The concentration is accomplished by way of purchase of shares. 2. The business activities of the undertakings concerned are: — for BMW: is globally active in the development, production and marketing of passenger cars and motorbikes. BMW and its affiliates also provide financial services for private and business customers, -

Daimler Truck North America Launche Reward Program

Daimler Truck North America Launche Reward Program 03 26, 2014 Contact: [email protected] LOUISVILLE, Ky., – (March 26, 2014) – Daimler Trucks North America (DTNA) is pleased to announce the official launch of its new customer rewards program for those who are searching for quality commercial truck and bus parts and services. The Truck Bucks℠ rewards program, rewards customers that shop within the DTNA network of Freightliner, Western Star, Detroit™ and Thomas Built Buses retail locations, while opening up a new channel of communication with its aftermarket customers across all brands. Through the Truck Bucks℠ rewards program, customers who are members of the program receive special incentives throughout the year. Specials include discounts on select parts and services, which are automatically deducted at checkout without the need for coupons or further action by the customer. “Truck Bucks℠ is a great opportunity for us to reward our customers for the parts and services that they purchase every day,” explains Paul Tuomi, director dealer and fleet parts sales, Daimler Trucks North America. “This rewards program will allow us to get closer to our best customers, and help us provide a better aftermarket experience.” With close to 800 retail locations, DTNA is one of the largest retail networks in the industry. DTNA has taken great lengths to improve the customer experience through the integration of new technologies and operational efficiencies at every stage of the customer ownership cycle. “We recognize that today, fleets and owneroperators are very conscious of their total cost of ownership,” added Tuomi. “To us, that means our parts and service operations have to be exceptional and provide value to our customers; this rewards program keeps us focused on that goal.” Customers are able to sign up for Truck Bucks online starting April 1 at www.MyTruckBucks.com or at any Freightliner, Western Star, Detroit™ or Thomas Built Buses retail location across the country. -

01 14 Canada Sales by Model.Qxp

Canada light-vehicle sales by nameplate, January 2014 Vehicles are domestic unless noted. Jan. Jan. Jan. Jan. Jan. Jan. Jan. Jan. 2014 2013 2014 2013 2014 2013 2014 2013 1 series (I) ........................................... 94 42 LaCrosse.............................................. 26 52 Rondo (I) ............................................. 387 216 IS (I)..................................................... 177 52 1 series (I) ........................................... 1 94 Regal.................................................... 43 98 Sedona (I)............................................ 36 78 LFA (I) .................................................. – 1 3 series (I) ........................................... 374 676 Verano.................................................. 222 226 Sorento ................................................ 864 753 LS (I).................................................... 12 11 4 series (I) ........................................... 111 – Total Buick car............................ 291 376 Sportage (I) ......................................... 413 422 Total Lexus car (I) ....................... 392 359 5 series (I) ........................................... 187 191 Enclave................................................. 167 195 Kia truck (D) .............................. 864 753 GX (I) ................................................... 60 26 6 series (I) ........................................... 27 18 Encore (I)............................................. 232 1 Kia truck (I) .............................. -

General Purchase Conditions Production Material and Spare Parts for Motor Vehicles Version 10/2018

General Purchase Conditions Production Material and Spare Parts for Motor Vehicles Version 10/2018 Exclusively for use with business persons acting in the course of invoice must be issued for each delivery note. Standard delivery notes business when concluding the contract. (DIN 4991) are to be used for all deliveries. 3.6 Invoices of Supplier shall only become due if the requirements of clause 1 Governing Conditions 3.5 are fulfilled. 1.1 These General Purchase Conditions apply to the supply of parts, spare parts, components, aggregates, and /or systems, including software 4 Notification of Defects contained therein or related software, for the use for motor vehicles. Daimler shall notify the Supplier of defects without undue delay as soon 1.2 The legal relations between Daimler AG, Stuttgart, or between one of its as they are discovered within the ordinary course of business. In so far affiliated companies (§15 of the German Stock Corporation Act (AktG)) the Supplier waives its right to object to the notification of defects on (hereinafter referred to as 'Daimler') and the Supplier (hereinafter the grounds of delay. collectively referred to as the 'Parties') shall, unless agreed otherwise, be governed by these General Purchase Conditions and the Mercedes- 5 Confidentiality, Use of Results Benz Special Terms (MBST) which are an integral part of these General 5.1 The Parties undertake to treat as business secrets all commercial and Purchase Conditions (hereinafter collectively referred to as 'Purchase technical details that become known to them in the course of the Conditions'). business relationship and that are not already in the public domain. -

Daimler at a Glance Financial Year 2017

Daimler at a Glance Financial Year 2017 www.daimler.com Daimler at a Glance 3 Group 4 Mercedes-Benz Cars 6 Daimler Trucks 12 Mercedes-Benz Vans 18 Daimler Buses 22 Daimler Financial Services 26 Our Brands and Divisions 30 All information in this brochure is current as of the publication date (February 2018). DAIMLER AT A GLANCE 3 Daimler at a Glance Daimler AG is one of the world’s most success- of the world and has production facilities in ful automotive companies. With its divisions Europe, North and South America, Asia, and Mercedes-Benz Cars, Daimler Trucks, Merce- Africa. des-Benz Vans, Daimler Buses and Daimler Financial Services, the Daimler Group is one Its current brand portfolio includes, in addi- of the biggest producers of premium cars tion to the world’s most valuable premium and the world’s biggest manufacturer of com- automotive brand, Mercedes-Benz (Source: mercial vehicles with a global reach. Daimler Interbrand-Study „The Anatomy of Growth“, Financial Services provides fi nancing, leasing, 10/5/2016), as well as Mercedes-AMG, fl eet management, insurance, fi nancial invest- Mercedes-Maybach and Mercedes me, the ments, credit cards, and innovative mobility brands smart, EQ, Freightliner, Western Star, services. BharatBenz, FUSO, Setra and Thomas Built Buses, and Daimler Financial Services’ brands: The company’s founders, Gottlieb Daimler Mercedes-Benz Bank, Mercedes-Benz Financial and Carl Benz, made history with the invention Services, Daimler Truck Financial, moovel, of the automobile in the year 1886. As a pio- car2go and mytaxi. The company is listed on neer of automotive engineering, it is a motiva- the stock exchanges of Frankfurt and Stuttgart tion and commitment of Daimler to shape (stock exchange symbol DAI). -

19-368 Ford Motor Co. V. Montana Eighth Judicial

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus FORD MOTOR CO. v. MONTANA EIGHTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF MONTANA No. 19–368. Argued October 7, 2020—Decided March 25, 2021* Ford Motor Company is a global auto company, incorporated in Delaware and headquartered in Michigan. Ford markets, sells, and services its products across the United States and overseas. The company also encourages a resale market for its vehicles. In each of these two cases, a state court exercised jurisdiction over Ford in a products-liability suit stemming from a car accident that injured a resident in the State. The first suit alleged that a 1996 Ford Explorer had malfunctioned, killing Markkaya Gullett near her home in Montana. In the second suit, Adam Bandemer claimed that he was injured in a collision on a Min- nesota road involving a defective 1994 Crown Victoria. Ford moved to dismiss both suits for lack of personal jurisdiction. It argued that each state court had jurisdiction only if the company’s conduct in the State had given rise to the plaintiff’s claims. And that causal link existed, according to Ford, only if the company had designed, manufactured, or sold in the State the particular vehicle involved in the accident. -

World Ex U.S. Value Portfolio

World Ex U.S. Value Portfolio As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings are subject to change. The information below represents the portfolio's holdings (excluding cash and cash equivalents) as of the date indicated, and may not be representative of the current or future investments of the portfolio. The information below should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any security. This listing of portfolio holdings is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed a recommendation to buy the securities. The holdings information below does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The holdings information has not been audited. By viewing this listing of portfolio holdings, you are agreeing to not redistribute the information and to not misuse this information to the detriment of portfolio shareholders. Misuse of this information includes, but is not limited to, (i) purchasing or selling any securities listed in the portfolio holdings solely in reliance upon this information; (ii) trading against any of the portfolios or (iii) knowingly engaging in any trading practices that are damaging to Dimensional or one of the portfolios. Investors should consider the portfolio's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses, which are contained in the Prospectus. Investors should read it carefully before investing. This fund operates as a fund-of-funds and generally allocates its assets among other mutual funds, but has the ability to invest in securities and derivatives directly. The holdings listed below contain both the investment holdings of the corresponding underlying funds as well as any direct investments of the fund. -

Tesla Motors: a Silicon Valley Version of the Automotive Business Model Tesla Motors – Revolutionizing the Driving Experience

Tesla Motors: A Silicon Valley Version of the Automotive Business Model Tesla Motors – Revolutionizing the Driving Experience What does it take to drive a revolution and Tesla is an American auto maker that revolutionize how we drive? It requires a makes luxury electric vehicles that Tesla has adopted digital company that is willing to radically re- retail anywhere between $70,000 and think a century-old automobile industry. A $100,000. The company has, to date, technologies like a true company that does not hold any aspects launched two models and announced digital native. of the traditional industry value chain multiple more. It has seen significant as sacred. This is about transforming appetite for its second model, Model S. everything: customer relations, the In overseas markets, such as Norway, mechanics of the car, and the accepted there were months where the model was business model. And consider that among the top-sellers1. The company all this is being done by a decade-old has also seen strong demand in its home company in a segment that is notoriously market (see Figure 1). difficult to penetrate – the luxury sedan market. That company is Tesla Motors, founded by Elon Musk, 43, a co-founder of payments company PayPal. Figure 1: Luxury Sedan Car Sales in the U.S. in 2013 18,000 13,303 10,932 10,727 6,300 5,421 Tesla Mercedes S-Class BMW 7-Series Lexus LS Audi A8 Porsche Panamera Model S Sedan Source: Forbes, “Tesla Sales Blow Past Competitors, But With Success Comes Scrutiny”, January 2014; Tesla Motors, “Tesla Motors Investor Presentation”, 2013 2 Tesla is determined to do things Tesla’s competitors have reportedly set differently. -

09 08 Light Truck Sales.Qxp

U.S. light-truck sales, September & 9 months 2008 Vehicles are domestic unless noted. Sept. Sept. 9 mos. 9 mos. Sept. Sept. 9 mos. 9 mos. Sept. Sept. 9 mos. 9 mos. 2008 2007 2008 2007 2008 2007 2008 2007 2008 2007 2008 2007 X3 (I) ....................................... 1,400 2,151 14,620 22,258 H1............................................ – 2 17 116 Grand Vitara (I)........................ 868 1,578 10,384 15,710 X5 ............................................ 2,316 2,293 24,663 24,319 H2............................................ 473 1,379 5,228 9,355 Vitara ....................................... – – – 1 X6 ............................................ 476 – 3,362 – H3............................................ 1,825 3,699 17,248 33,289 XL-7 (D)................................. 361 1,620 19,655 18,356 Total BMW Group (D) ............. 2,792 2,293 28,025 24,319 Total Hummer ...................... 2,298 5,080 22,493 42,760 XL7 (I) ................................... – 6 6 508 Total BMW Group (I) .............. 1,400 2,151 14,620 22,258 Aztek........................................ – – – 25 Total XL-7/XL7......................... 361 1,626 19,661 18,864 BMW GROUP ........................ 4,192 4,444 42,645 46,577 Montana................................... – – – 26 Suzuki (D)........................... 361 1,620 19,655 18,357 Aspen....................................... 1,313 3,875 17,681 22,468 Montana SV6 ........................... – 39 64 1,270 Suzuki (I)............................ 868 1,584 10,390 16,218 Pacifica .................................... 544 4,183 5,621 42,874 Torrent ..................................... 1,486 3,403 16,854 26,141 SUZUKI ............................... 1,229 3,204 30,045 34,575 Town & Country....................... 9,229 8,681 95,287 99,134 Total Pontiac ....................... 1,486 3,442 16,918 27,462 Freelander (I) ........................... – – – 1 Total Chrysler Division............ 11,086 16,739 118,589 164,476 Outlook ...................................