19-368 Ford Motor Co. V. Montana Eighth Judicial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collecting Money from a Small Claims Judgment

If the defendant is not present at the fies the defendant and his/her property. trial, the court will send a copy of the small claims judgment to the defendant. The • If you have the information described judgment will order the defendant to pay above, you can start the process for an you in full within 21 days or tell you and the order to seize property or for garnishment. court where s/he works and the location of his/her bank accounts. • If you don't have the information described above, you will need to order the 3. If the defendant doesn't pay the defendant to appear in court for questioning judgment as ordered, you will have to through a process called discovery. You can collect your money through a seizure of start this process by filing a discovery subpoena. property or a garnishment. Filing a Discovery Subpoena COLLECTING MONEY FROM A What Is Seizure of Property? You must wait 21 days after your small SMALL CLAIMS JUDGMENT Seizure of property is a court procedure claims judgment was signed before you can allowing a court officer to seize property file a discovery subpoena. Form MC 11, If you sued someone for money and belonging to the defendant which can be sold Subpoena (Order to Appear), can be used. received a judgment against that person, you to pay for your judgment. If you want to file a have the right to collect the money. request to seize property, you may use form Contact the court for an appearance date MC 19, Request and Order to Seize Property. -

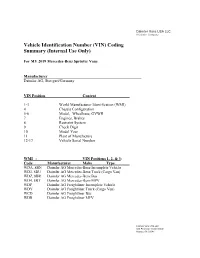

Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) Coding Summary (Internal Use Only)

Daimler Vans USA LLC A Daimler Company Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) Coding Summary (Internal Use Only) For MY 2019 Mercedes-Benz Sprinter Vans Manufacturer Daimler AG, Stuttgart/Germany VIN Position Content 1-3 World Manufacturer Identification (WMI) 4 Chassis Configuration 5-6 Model, Wheelbase, GVWR 7 Engines, Brakes 8 Restraint System 9 Check Digit 10 Model Year 11 Plant of Manufacture 12-17 Vehicle Serial Number WMI - VIN Positions 1, 2, & 3: Code Manufacturer Make Type WDA, 8BN Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz Incomplete Vehicle WD3, 8BU Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz Truck (Cargo Van) WDZ, 8BR Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz Bus WD4, 8BT Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz MPV WDP Daimler AG Freightliner Incomplete Vehicle WDY Daimler AG Freightliner Truck (Cargo Van) WCD Daimler AG Freightliner Bus WDR Daimler AG Freightliner MPV Daimler Vans USA LLC 303 Perimeter Center North Atlanta, GA 30346 Daimler Vans USA LLC A Daimler Company Chassis Configuration - VIN Position 4: Code Chassis Configuration / Intended Market P All 4x2 Vehicle Types / U.S. B All 4x2 Vehicle Types / Canada F All 4x4 Vehicle Types / U.S. C All 4x4 Vehicle Types / Canada Model, Wheelbase, GVWR - VIN Positions 5 & 6: Code Model Wheelbase GVWR E7 C1500/C2500/P1500 3665 mm/ 144 in. 8,000 lbs. to 9,000 lbs. Class G E8 C2500/P2500 4325 mm/ 170 in. 8,000 lbs. to 9,000 lbs. Class G F0 C2500/C3500 3665 mm/ 144 in. 9,000 lbs. to 10,000 lbs. Class H F1 C2500/C3500 4325 mm/ 170 in. 9,000 lbs. to 10,000 lbs. Class H F3 C4500/C3500 3665 mm/ 144 in. -

Daimler AG, Formerly Known As

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION, 100 F Street,NE Washington, DC 20549-6030 Case: 1:10-cv-00473 Plaintiff, Ass~gned To : Leon, RichardJ-.- ASSIgn. Date: 3/22/2010 v. Description: General Civil DAIMLERAG, .Mercedesstrasse 137 70327 . Stuttgart, Germany Defendant. COMPLAINT PlaintiffUnited States Securities and Exchange Commission ("Commission") alleges that: SUMMARY OF THE ACTION 1. From at least 1998 through 2008, Daimler AG, formerly knoWn as DaimlerChrysler AG ("Daimler" or the "Company"), and certain ofits subsidiaries and affiliates, violated the anti-bribery, books and records and internal controls provisions ofthe Foreign _ Corrupt Practices Act (the "FCPA") by making illicit payments, directly or indirectly, to foreign government officials in order to secure and maintain business worldWide. 2. During this time period, Daimler paid bribes to government officials to further government sales in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe and the Middle East. In connection With at least 51 transactions, Daimler violated the anti-bribery provision of the FCPA by paying tens of millions of dollars in corrupt payments to foreign government officials to secure business in · Russia,Chilia,Vietnam, Nigeria, Hungary, Latvia, Croatia and Bosnia. These corrupt payments were made through the use ofU.S. mails or the means or instrumentality ofU.S. interstate commerce. 3. Daimler also violated the FCPA's books and records and internal controls provisions in connection with the 51 transactions and at least an additional 154 transactions, in which it made improper payments totaling atleast $56 million to secure business in 22 countries, including, among others, Russia, China, Nigeria, Vietnam, Egypt, Greece, Hungary, North Korea, andIndonesia. -

Auto Retailing: Why the Franchise System Works Best

AUTO RETAILING: WHY THE FRANCHISE SYSTEM WORKS BEST Q Executive Summary or manufacturers and consumers alike, the automotive and communities—were much more highly motivated and franchise system is the best method for distributing and successful retailers than factory employees or contractors. F selling new cars and trucks. For consumers, new-car That’s still true today, as evidenced by some key findings franchises create intra-brand competition that lowers prices; of this study: generate extra accountability for consumers in warranty and • Today, the average dealership requires an investment of safety recall situations; and provide enormous local eco- $11.3 million, including physical facilities, land, inventory nomic benefits, from well-paying jobs to billions in local taxes. and working capital. For manufacturers, the franchise system is simply the • Nationwide, dealers have invested nearly $200 billion in most efficient and effective way to distribute and sell automo- dealership facilities. biles nationwide. Franchised dealers invest millions of dollars Annual operating costs totaled $81.5 billion in 2013, of private capital in their retail outlets to provide top sales and • an average of $4.6 million per dealership. These service experiences, allowing auto manufacturers to concen- costs include personnel, utilities, advertising and trate their capital in their core areas: designing, building and regulatory compliance. marketing vehicles. Throughout the history of the auto industry, manufactur- • The vast majority—95.6 percent—of the 17,663 ers have experimented with selling directly to consumers. In individual franchised retail automotive outlets are locally fact, in the early years of the industry, manufacturers used and privately owned. -

“Law of Precedent”

1 Summary of papers written by Judicial Officers on the subje ct: ªLAW OF PRECEDENTº Introduction :- A precedent is a statement of law found in the decision of a superior Court, which decision has to be followed by that court and by the courts inferior to it. Precedent is a previous decision upon which the judges have to follow the past decisions carefully in the cases before them as a guide for all present or future decisions. In other words, `Judicial Precedent' means a judgment of a Court of law cited as an authority for deciding a similar set of facts, a case which serves as authority for the legal principle embodied in its decision. A judicial precedent is a decision of the Court used as a source for future decision making. Meaning :- A precedent is a statement of law found in decision of a Superior Court. Though law making is the work of the legislature, Judges make law through the precedent. 2 Inferior courts must follow such laws. Decisions based on a question of law are precedents. Decisions based on question of facts are not precedents. Judges must follow the binding decisions of Superior or the same court. Following previous binding decisions brings uniformity in decision making, not following would result in confusion. It is well settled that Article 141 of the Constitution empowers the Supreme Court to declare the law and not to enact the law, which essentially is the function of the legislature. To declare the law means to interpret the law. This interpretation of law is binding on all the Courts in India. -

Guidelines to Help Lawyers Practicing in the Court of Chancery

GUIDELINES TO HELP LAWYERS PRACTICING IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY The vast majority of attorneys who litigate in and appear before the Court conduct themselves in accordance with the highest traditions of Chancery practice. These Guidelines are intended to ensure that all attorneys are aware of the expectations of the Court and to provide helpful guidance in practicing in our Court. These Guidelines are not binding Court Rules, they are intended as a practice aid that will allow our excellent Bar to handle cases even more smoothly and to minimize disputes over process, rather than the substantive merits. These Guidelines do not establish a “standard of conduct” or a “standard of care” by which the performance of attorneys in a given case can or should be measured. The Guidelines are not intended to be used as a sword to wound adversaries. To the contrary, they are intended to reduce conflicts among counsel and parties over non-merits issues, and allow them to more efficiently and less contentiously handle their disputes in this Court. Accordingly, the Court does not intend that these Guidelines, or the sample forms attached hereto, be cited as authority in the context of any dispute before the Court. These guidelines reflect some suggested best practices for moving cases forward to completion in the Court of Chancery. They have been developed jointly by the Court and its Rules Committee to provide help to practitioners. The members of the Court and its Rules Committee recognize that a particular situation may call for the parties to proceed in a different manner. -

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

Examples of Meritorious Summary Judgment Motions

Examples of meritorious summary judgment motions By: Douglas H. Wilkins and Daniel I. Small February 13, 2020 Our last two columns addressed the real problem of overuse of summary judgment. Underuse is vanishingly rare. Even rarer (perhaps non-existent) is the case in which underuse ends up making a difference in the long run. But there are lessons to be learned by identifying cases in which you really should move for summary judgment. It is important to provide a reference point for evaluating the wisdom of filing a summary judgment motion. Here are some non-exclusive examples of good summary judgment candidates. Unambiguous written document: Perhaps the most common subject matter for a successful summary judgment motion is the contracts case or collections matter in which the whole dispute turns upon the unambiguous terms of a written note, contract, lease, insurance policy, trust or other document. See, e.g. United States Trust Co. of New York v. Herriott, 10 Mass. App. Ct. 131 (1980). The courts have said, quite generally, that “interpretation of the meaning of a term in a contract” is a question of law for the court. EventMonitor, Inc. v. Leness, 473 Mass. 540, 549 (2016). That doesn’t mean all questions of contract interpretation — just the unambiguous language. When the language of a contract is ambiguous, it is for the fact-finder to ascertain and give effect to the intention of the parties. See Acushnet Company v. Beam, Inc., 92 Mass. App. Ct. 687, 697 (2018). Ambiguous contracts are therefore not fodder for summary judgment. Ironically, there may be some confusion about what “unambiguous” means. -

Daimler Annual Report 2014

Annual Report 2014. Key Figures. Daimler Group 2014 2013 2012 14/13 Amounts in millions of euros % change Revenue 129,872 117,982 114,297 +10 1 Western Europe 43,722 41,123 39,377 +6 thereof Germany 20,449 20,227 19,722 +1 NAFTA 38,025 32,925 31,914 +15 thereof United States 33,310 28,597 27,233 +16 Asia 29,446 24,481 25,126 +20 thereof China 13,294 10,705 10,782 +24 Other markets 18,679 19,453 17,880 -4 Investment in property, plant and equipment 4,844 4,975 4,827 -3 Research and development expenditure 2 5,680 5,489 5,644 +3 thereof capitalized 1,148 1,284 1,465 -11 Free cash flow of the industrial business 5,479 4,842 1,452 +13 EBIT 3 10,752 10,815 8,820 -1 Value added 3 4,416 5,921 4,300 -25 Net profit 3 7,290 8,720 6,830 -16 Earnings per share (in €) 3 6.51 6.40 6.02 +2 Total dividend 2,621 2,407 2,349 +9 Dividend per share (in €) 2.45 2.25 2.20 +9 Employees (December 31) 279,972 274,616 275,087 +2 1 Adjusted for the effects of currency translation, revenue increased by 12%. 2 For the year 2013, the figures have been adjusted due to reclassifications within functional costs. 3 For the year 2012, the figures have been adjusted, primarily for effects arising from application of the amended version of IAS 19. Cover photo: Mercedes-Benz Future Truck 2025. -

2002 Ford Motor Company Annual Report

2228.FordAnnualCovers 4/26/03 2:31 PM Page 1 Ford Motor Company Ford 2002 ANNUAL REPORT STARTING OUR SECOND CENTURY STARTING “I will build a motorcar for the great multitude.” Henry Ford 2002 Annual Report STARTING OUR SECOND CENTURY www.ford.com Ford Motor Company G One American Road G Dearborn, Michigan 48126 2228.FordAnnualCovers 4/26/03 2:31 PM Page 2 Information for Shareholders n the 20th century, no company had a greater impact on the lives of everyday people than Shareholder Services I Ford. Ford Motor Company put the world on wheels with such great products as the Model T, Ford Shareholder Services Group Telephone: and brought freedom and prosperity to millions with innovations that included the moving EquiServe Trust Company, N.A. Within the U.S. and Canada: (800) 279-1237 P.O. Box 43087 Outside the U.S. and Canada: (781) 575-2692 assembly line and the “$5 day.” In this, our centennial year, we honor our past, but embrace Providence, Rhode Island 02940-3087 E-mail: [email protected] EquiServe Trust Company N.A. offers the DirectSERVICE™ Investment and Stock Purchase Program. This shareholder- paid program provides a low-cost alternative to traditional retail brokerage methods of purchasing, holding and selling Ford Common Stock. Company Information The URL to our online Investor Center is www.shareholder.ford.com. Alternatively, individual investors may contact: Ford Motor Company Telephone: Shareholder Relations Within the U.S. and Canada: (800) 555-5259 One American Road Outside the U.S. and Canada: (313) 845-8540 Dearborn, Michigan 48126-2798 Facsimile: (313) 845-6073 E-mail: [email protected] Security analysts and institutional investors may contact: Ford Motor Company Telephone: (313) 323-8221 or (313) 390-4563 Investor Relations Facsimile: (313) 845-6073 One American Road Dearborn, Michigan 48126-2798 E-mail: [email protected] To view the Ford Motor Company Fund and the Ford Corporate Citizenship annual reports, go to www.ford.com. -

MONTANA BIRTH CERTIFICATE APPLICATION Cascade County Clerk & Recorder, 121 4Th St N Ste 1B1 Great Falls, MT 59401 406-454-6718 IDENTIFICATION IS REQUIRED Picture I.D

INSTRUCTIONS FOR ORDERING A BIRTH RECORD 1. Print, Fill out completely, and Sign application. (see below for who can order) 2. Provide proof of Identity (see acceptable methods below) 3. Enclose cashier’s check or money order (see Fees below) 4. Enclose a stamped self-addressed return envelope. (enclose a pre-paid envelope from express mail/UPS/FEDEX etc. for expedited service. We do not track mail once it leaves our office - keep all tracking info) 5. Mail application, I.D., payment, and return envelope to Cascade County Clerk and Recorder, 121 4th St N, Suite 1B1 Great Falls, MT 59401 WHO CAN ORDER A CERTIFIED BIRTH CERTIFICATE? Only those authorized by 50-15-121 MCA, which includes the registrant (14 years old or older) the registrant’s spouse, children, parents or guardian or an authorized representative, may obtain a certified copy of a birth record. Proof of relationship, guardianship or authorization is required. Step-relatives, in-laws, grandparents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins, ex-spouses, and a natural parent of an adoptive child or others are NOT eligible to receive a certified copy of a birth certificate. Non-certified informational/genealogy copies are available to anyone if record is more than 30 years old. Montana birth certificates are full size paper with a raised seal. Wallet size cards are not available. IDENTIFICATION IS REQUIRED •The person signing the request must provide an enlarged legible photocopy of both sides of their valid driver’s license or other legal picture identification with a signature, or the requestor must have the application notarized. -

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La.