Auto Retailing: Why the Franchise System Works Best

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation and Intermediaries in the Music Industry

CREATe Working Paper 2017/07 (June 2017) Digitalisation and intermediaries in the Music Industry Authors Morten Hviid Sabine Jacques Sofia Izquierdo Sanchez Centre for Competition Policy, Centre for Competition Policy, Department of Accountancy, Finance, University of East Anglia University of East Anglia and Economics, University of Huddersfield [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] CREATe Working Paper Series DOI:10.5281/zenodo.809949 This release was supported by the RCUK funded Centre for Copyright and New Business Models in the Creative Economy (CREATe), AHRC Grant Number AH/K000179/1. Abstract Prior to digitalisation, the vertical structure of the market for recorded music could be described as a large number of artists [composers, lyricists and musicians] supplying creative expressions to a small number of larger record labels and publishers who funded, produced, and marketed the resulting recorded music to subsequently sell these works to consumers through a fragmented retail sector. We argue that digitalisation has led to a new structure in which the retail segment has also become concentrated. Such a structure, with successive oligopolistic segments, can lead to higher consumer prices through double marginalisation. We further question whether a combination of disintermediation of the record labels function combined with “self- publishing” by artists, will lead to the demise of powerful firms in the record label segment, thus shifting market power from the record label and publisher segment to the retail segment, rather than increasing the number of segments with market power. i Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 2. How the advancement of technologies shapes the music industry ................................. -

General Rental Information

GENERAL RENTAL INFORMATION Our rates include: unlimited mileage (except when indicated differently), reduction for damage and theft, car radio, VAT road tax, preparation of the vehicle, registration fees. Our rates do not include: total elimination of penalty reduction for damage and theft, fuel, refuelling service charge, fines, optional clauses (Mini Kasko, Pai, Super Kasko, Gold Kasko, Road Assistance and Plus), extras, supplements, fees for additional services related to fines, tolls, parking tickets and any penalties or charges imposed by authorities, entities, dealers in relation to the circulation of the vehicle, and anything not expressly included. Please note: Vehicles must be returned during office opening hours. If the customer returns the vehicle during the closure of the local office, he will be held liable for all damage to the vehicle that could be caused during the time between the vehicle has been parked and the opening of our office when our local staff collect it. If the rental period exceeds 30 days, you must complete the procedure and accept the obligations deriving from article 94, paragraph 4 bis of the Italian Road Traffic Code, referring to the update of the Vehicles National Register. JOPARKING SRL is not responsible for anything that may occur in the event of non- compliance with these obligations. The vehicle is delivered in perfect condition and it has to return back in the same conditions. Minimum and maximum age: Minimum age allowed for car rental is 23 years. If the driver's age is between 19-20 years of age, upon payment of the "Young Driver", at a cost of € 24.59 + VAT per day, it is possible to rent cars belonging to the groups A/B/C. -

Daimler Annual Report 2014

Annual Report 2014. Key Figures. Daimler Group 2014 2013 2012 14/13 Amounts in millions of euros % change Revenue 129,872 117,982 114,297 +10 1 Western Europe 43,722 41,123 39,377 +6 thereof Germany 20,449 20,227 19,722 +1 NAFTA 38,025 32,925 31,914 +15 thereof United States 33,310 28,597 27,233 +16 Asia 29,446 24,481 25,126 +20 thereof China 13,294 10,705 10,782 +24 Other markets 18,679 19,453 17,880 -4 Investment in property, plant and equipment 4,844 4,975 4,827 -3 Research and development expenditure 2 5,680 5,489 5,644 +3 thereof capitalized 1,148 1,284 1,465 -11 Free cash flow of the industrial business 5,479 4,842 1,452 +13 EBIT 3 10,752 10,815 8,820 -1 Value added 3 4,416 5,921 4,300 -25 Net profit 3 7,290 8,720 6,830 -16 Earnings per share (in €) 3 6.51 6.40 6.02 +2 Total dividend 2,621 2,407 2,349 +9 Dividend per share (in €) 2.45 2.25 2.20 +9 Employees (December 31) 279,972 274,616 275,087 +2 1 Adjusted for the effects of currency translation, revenue increased by 12%. 2 For the year 2013, the figures have been adjusted due to reclassifications within functional costs. 3 For the year 2012, the figures have been adjusted, primarily for effects arising from application of the amended version of IAS 19. Cover photo: Mercedes-Benz Future Truck 2025. -

2002 Ford Motor Company Annual Report

2228.FordAnnualCovers 4/26/03 2:31 PM Page 1 Ford Motor Company Ford 2002 ANNUAL REPORT STARTING OUR SECOND CENTURY STARTING “I will build a motorcar for the great multitude.” Henry Ford 2002 Annual Report STARTING OUR SECOND CENTURY www.ford.com Ford Motor Company G One American Road G Dearborn, Michigan 48126 2228.FordAnnualCovers 4/26/03 2:31 PM Page 2 Information for Shareholders n the 20th century, no company had a greater impact on the lives of everyday people than Shareholder Services I Ford. Ford Motor Company put the world on wheels with such great products as the Model T, Ford Shareholder Services Group Telephone: and brought freedom and prosperity to millions with innovations that included the moving EquiServe Trust Company, N.A. Within the U.S. and Canada: (800) 279-1237 P.O. Box 43087 Outside the U.S. and Canada: (781) 575-2692 assembly line and the “$5 day.” In this, our centennial year, we honor our past, but embrace Providence, Rhode Island 02940-3087 E-mail: [email protected] EquiServe Trust Company N.A. offers the DirectSERVICE™ Investment and Stock Purchase Program. This shareholder- paid program provides a low-cost alternative to traditional retail brokerage methods of purchasing, holding and selling Ford Common Stock. Company Information The URL to our online Investor Center is www.shareholder.ford.com. Alternatively, individual investors may contact: Ford Motor Company Telephone: Shareholder Relations Within the U.S. and Canada: (800) 555-5259 One American Road Outside the U.S. and Canada: (313) 845-8540 Dearborn, Michigan 48126-2798 Facsimile: (313) 845-6073 E-mail: [email protected] Security analysts and institutional investors may contact: Ford Motor Company Telephone: (313) 323-8221 or (313) 390-4563 Investor Relations Facsimile: (313) 845-6073 One American Road Dearborn, Michigan 48126-2798 E-mail: [email protected] To view the Ford Motor Company Fund and the Ford Corporate Citizenship annual reports, go to www.ford.com. -

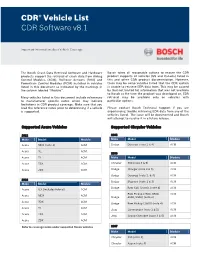

V8.1 Supported Vehicle List

® CDR Vehicle List CDR Software v8.1 Important Information about Vehicle Coverage The Bosch Crash Data Retrieval Software and Hardware Bosch takes all reasonable actions to ensure the CDR products support the retrieval of crash data from Airbag product supports all vehicles (US and Canada) listed in Control Modules (ACM), Roll-over Sensors (ROS) and this and other CDR product documentation. However, Powertrain Control Modules (PCM) installed in vehicles there may be some vehicles listed that the CDR system listed in this document as indicated by the markings in is unable to retrieve EDR data from. This may be caused the column labeled ‘‘Module’’. by (but not limited to) information that was not available to Bosch at the time the product was developed or, EDR Many vehicles listed in this document include references retrieval may be available only on vehicles with to manufacturer specific notes which may indicate particular options. limitations in CDR product coverage. Make sure that you read the reference notes prior to determining if a vehicle Please contact Bosch Technical Support if you are is supported. experiencing trouble retrieving EDR data from any of the vehicles listed. The issue will be documented and Bosch will attempt to resolve it in a future release. Supported Acura Vehicles Supported Chrysler Vehicles 2012 2005 Make Model Module Make Model Module Acura MDX (note 1) ACM Dodge Durango (note 2 & 4) ACM Acura RL ACM 2006 Acura TL ACM Make Model Module Acura TSX ACM Chrysler 300 (note 3 & 5) ACM Acura ZDX ACM Dodge Charger (note -

Mobile Air Conditioner Leakage Rates Model Year 2016 (Alphabetical List)

Mobile Air Conditioner Leakage Rates Model Year 2016 (Alphabetical List) Leakage Rate AC Charge Size Percentage loss per Make Model (MY 2016) Type of Vehicle (grams/year) (grams) year Ford Fusion 1.6L GDTI Passenger Car 7.8 570 1.4 Ford Fusion 2.5L iVCT Passenger Car 8.7 680 1.3 Ford Escape 1.6L GTDI SUV 8.4 680 1.2 Ford Escape 2.5L SUV 8.0 680 1.2 Ford Police Interceptor Sedan 3.5 GTDI Passenger Car 9.6 740 1.3 Ford Police Interceptor Sedan 3.5L/3.7L TiVCT Passenger Car 9.8 650 1.5 Ford Ford Focus RS 2.3L GDTI RS Passenger Car 7.4 600 1.2 Ford Mustang Shelby GT500 5.2L Passenger Car 7.1 650 1.1 Ford Transit 3.5L GTDI V6 148" wheelbase ext body (dual) Van 8.1 1190 0.7 Ford Transit 3.5L GTDI V6 148" wheelbase (dual) Van 8.0 1190 0.7 Ford Transit 3.5L GTDI V6 130" wheelbase (dual) Van 7.9 1190 0.7 Ford Transit 3.7L TIVCT V6 148" wheelbase ext body (dual) Van 8.1 1110 0.7 Ford Transit 3.7L TIVCT V6 148" wheelbase (dual) Van 8.0 1110 0.7 Ford Transit 3.7L TIVCT V6 130" wheelbase (dual) Van 7.9 1110 0.7 Ford Trainsit 3.7L TIVCT And 3.5L GTDI V6 Van 7.2 790 0.9 Ford Transit 3.2L Diesle I5, 148" wheelbase ext body (dual) Van 8.3 1110 0.7 Ford Transit 3.2L Diesel I5, 148" wheelbase (dual) Van 8.2 1110 0.7 Ford Transit 3.2L Diesel I5, 130" wheelbase (dual) Van 8.1 1110 0.7 Ford Transit 3.2L Diesel I5 Van 7.4 790 0.9 Ford Fiesta 1.0L TiVCT GDTI Passenger Car 7.4 680 1.1 Ford Fiesta 1.6L TiVCT GDTI Passenger Car 7.4 680 1.1 Ford Fiesta 1.6L TiVCT Passenger Car 7.4 600 1.2 Ford Transit Connect 2.5L (Dual) Van 7.8 880 0.9 Ford Transit Connect 2.5L Van 7.3 680 1.1 Ford Transit Connect 1.6L GTDI (Dual) Van 7.9 880 0.9 Ford Transit Connect 1.6L GTDI Van 7.4 680 1.1 Ford Edge 3.5L V6 TiVCT SUV 8.4 680 1.2 Ford MKX 3.7L V6 TiVCT SUV 8.4 680 1.2 Ford Edge 2.0L I4 GTDI SUV 8.7 680 1.3 Ford Police Interceptor Utility 3.5L GTDI SUV 10.3 960 1.1 Ford Police Interceptor utility 3.7L TiVCT SUV 10.4 740 1.4 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency • 520 Lafayette Rd. -

Value Growth and the Music Industry: the Untold Story of Digital Success by Maud Sacquet October 2017

RESEARCH PAPER Value Growth and the Music Industry: The Untold Story of Digital Success By Maud Sacquet October 2017 Executive Summary societies’ collections increased 26% globally between 2007 and 2015. Meanwhile, European consumers and For music listeners, digitisation and the internet tell a businesses are the highest contributors globally to story of increased consumer welfare1. Today, consumers collecting societies’ revenues. have access to a greater choice of music than ever before and can listen to music anywhere, anytime, on a broad range of devices. And with all these increased These figures undermine the case for an alleged “value choices has come an explosion of sharing and creativity. gap”, showing instead healthy rises in revenue. These figures demonstrate that digital’s efficiency savings are From the creative industry side, the internet has also passed on to both consumers and record labels — and enabled new business models for creators and the hence that digital streaming services enable massive emergence of new artists and music intermediaries. It value growth. has also allowed independent labels to thrive — in Adele’s producer’s own words, digital music is a “more level playing field”2. The supply side of music is more Introduction diverse and competitive than ever. The current debate in the European Union on copyright Have these gains been achieved at the expense of reform is in part focused on an alleged “value gap”, legacy music players, such as major labels and defined in May 2016 by the International Federation collecting societies? of the Phonographic Industry (“IFPI”) as “the dramatic contrast between the proportionate revenues In this paper, we look at data from major record labels generated by user upload services and by paid and from collecting societies to answer this question. -

AALA2009 Percentages R1.Xls 8/7/2009

Page 1 AALA2009 Percentages_r1.xls 8/7/2009 Passenger car Other Vehicle Type Manufactured in: Manufactured in: Percent Content US/ US/ US/ Manufacturers Makes Carlines Models Canada Canada Outside Canada Outside American Honda Acura RL 0% X American Honda Acura TSX 0% X American Honda Honda Fit 0% X American Honda Honda S2000 0% X American Suzuki Motor Suzuki Grand Vitara 0% X American Suzuki Motor Suzuki SX4 0% X 612 Scaglietti, Scaglietti F1 & 599 GTB Fiat Ferrari Fiorano/F1 0% X F430/F430 F1, F430 Spider, F430 Spider F1, 430 Scuderia & Fiat Ferrari Scuderia Spider 16M 0% X Fuyi Heavy Industries Subaru Forester 0% X Fuyi Heavy Industries Subaru Impreza 0% X Lotus Lotus Elise/Exige0%X Mazda Motor Corp. Mazda CX-7 0% X Mazda3 - 4D Sedan & Mazda Motor Corp. Mazda Hatchback 0% Mazda Motor Corp. Mazda Mazda5 0% X Mazda Motor Corp. Mazda MX-5 Miata 0% X Mazda Motor Corp. Mazda RX-8 0% X Mercedes Benz Mercedes C-Class 0% X Mercedes Benz Mercedes CL & CLS 0% X CLK-Class, Mercedes Benz Mercedes Cabriolet/Coupe 0% X Mercedes Benz Mercedes E-Class 0% X Mercedes Benz Mercedes G-Class 0% X Mercedes Benz Mercedes Maybach 0% X Mercedes Benz Mercedes S & SL Class 0% X Mercedes Benz Mercedes SLK-Class 0% X Mercedes Benz Mercedes SLR 0% X Mitsubishi Motors Mitsubishi Lancer 0% X Mitsubishi Motors Mitsubishi Outlander 0% X Nissan North America Infiniti EX35 0% X Nissan North America Infiniti FX35/50 0% X G37 Sedan, Coupe, Nissan North America Infiniti Convertible 0% X Nissan North America Infiniti M35/45 0% X Nissan North America Nissan 350Z Convertible -

Toyota in the World 2011

"Toyota in the World 2011" is intended to provide an overview of Toyota, including a look at its latest activities relating to R&D (Research & Development), manufacturing, sales and exports from January to December 2010. It is hoped that this handbook will be useful to those seeking to gain a better understanding of Toyota's corporate activities. Research & Development Production, Sales and Exports Domestic and Overseas R&D Sites Overseas Production Companies North America/ Latin America: Market/Toyota Sales and Production Technological Development Europe/Africa: Market/Toyota Sales and Production Asia: Market/Toyota Sales and Production History of Technological Development (from 1990) Oceania & Middle East: Market/Toyota Sales and Production Operations in Japan Vehicle Production, Sales and Exports by Region Overseas Model Lineup by Country & Region Toyota Group & Supplier Organizations Japanese Production and Dealer Sites Chronology Number of Vehicles Produced in Japan by Model Product Lineup U.S.A. JAPAN Toyota Motor Engineering and Manufacturing North Head Office Toyota Technical Center America, Inc. Establishment 1954 Establishment 1977 Activities: Product planning, design, Locations: Michigan, prototype development, vehicle California, evaluation Arizona, Washington D.C. Activities: Product planning, Vehicle Engineering & Evaluation Basic Research Shibetsu Proving Ground Establishment 1984 Activities: Vehicle testing and evaluation at high speed and under cold Calty Design Research, Inc. conditions Establishment 1973 Locations: California, Michigan Activities: Exterior, Interior and Color Design Higashi-Fuji Technical Center Establishment 1966 Activities: New technology research for vehicles and engines Toyota Central Research & Development Laboratories, Inc. Establishment 1960 Activities: Fundamental research for the Toyota Group Europe Asia Pacific Toyota Motor Europe NV/SA Toyota Motor Asia Pacific Engineering and Manfacturing Co., Ltd. -

11 Electric Vehicle Stocks to Buy for 2021

INVESTOR PLACE 11 ELECTRIC VEHICLE STOCKS TO BUY FOR 2021 LUKE LANGO How to turn the electric disruption of transportation into your million-dollar opportunity When it comes to identifying next-generation breakthrough investments that could rise 100%, 200%, 500%, or more, I always come back to one saying. Where there’s disruption, there’s opportunity. Case-in-point: The internet. Throughout the 1990s, the emergence of the internet rapidly disrupted how people across the globe worked, communicated, and played. For many, it was a scary time. Change is never easy. For many more, it was an exciting time, as the internet was unlocking a new world of possibilities. But… for investors… it was an opportunity. Specifically, it was a once-in-a-decade opportunity to invest early in emerging titans of the internet industry. Like Amazon (AMZN)… when it was a $438 million company in 1997… It’s a $1.6 TRILLION company today – representing a whopping 365,000% return. That means a mere $1,000 investment in Amazon in 1997 would be worth more than $3.6 million today. 2 Luke Lango’s Hypergrowth Investing Need I say more? Where there’s disruption, there’s opportunity – and the bigger the disruption, the bigger the opportunity. Right now, we are on the cusp of an enormous disruption. This disruption will fundamentally and entirely change the world’s multi-trillion-dollar transportation work. In its wake, it will create new hundred-billion-dollar titans of the auto industry – most of whom are just tiny companies today. What disruption am I talking about specifically? The shift toward electric vehicles. -

The Struggle for Dominance in the Automobile Market: the Early Years of Ford and General Motors

The Struggle for Dominance in the Automobile Market: The Early Years of Ford and General Motors Richard S. Tedlow Harvard University This paper contrasts the business strategics of Henry Ford and Alfred P. Sloan,Jr. in the automobilemarket of the 1920s.1 The thesisis that HenryFord epitomized the method of competition most familiar to ncoclassical economics. That is to say, his key competitive weapon was price. Alfred P. Sloan, Jr. beat Ford because hc understood that the nature of the market had changed and that new tools wcrc nccdcd for success in the modern world of oligopolistic competition. Henry Ford and the Old Competition In the world of ncoclassical economics, the business landscape is studdcd with anonymous, small producers and merchants and the consumer has perfect information. Buyers do not know other buyers; buyers do not know sellers;scllcrs do not know other sellers. No scllcr can, without collusion, raise price by restricting output. It is a world of commodities. All products arc undiffcrcntiatcd. Prices arc established through the mechanism of an impersonal market, where the "invisible hand" ensures consumer welfare. Producers in an untrammeled market system have no choice but to accept "the lowest [pricc] which can bc taken" [19, p. 61]. In Adam $mith's world, business people do not lose sleep over the issue of whether or not to compete on price. Pricc is compctition's defining characteristic. Conditions approximating this description may have existed in the United States prior to the railroad revolution of the 1840s [6, pp. 13-78]. With thc building of the railroad network, however, the context of businessactivity began to change. -

Collisions with Passenger Cars and Moose, Sweden U

Collisions with Passenger Cars and Moose, Sweden U. BJORNSTIG, MD, PHD, A. ERIKSSON, MD, PHD, J. THORSON, MD, PHD, AND P-O BYLUND, UC The passenger car sizes have been classified according Abstract: The number of collisions between motor vehicles and to weight, with "small" denoting <1,100 kg, "medium- moose is increasing in many countries. Collisions with large, high sized" from 1,100-1,450 kg, and "large" cars >1,450 kg. animals such as moose cause typical rear- and downward deforma- The percentage of cars of different sizes was 38 per cent, 53 tion of the windshield pillars and front roof, most pronounced for per cent and 10 per cent, respectively. small passenger cars; the injury risk increases with the deformation The persons interviewed usually had a clear idea of the of the car. A strengthening of the windshield pillars and front roof deformation ofthe windshield pillars (A-pillars) and car roof; and the use of antilacerative windshields would reduce the injury 15 per cent had taken photographs which verified the accu- risk to car occupants. (Am J Public Health 1986; 76:460462.) racy of the answers given. All data presented have been projected to reflect 650 accidents involving 1,309 car occupants (of whom 989 were Introduction injured). In the Figures 2-4, numbers superimposed on vertical bars denote this projected number. Sampling uncer- In Sweden, the number of reported road accidents tainty ranges from ±2.5 per cent at the 5-95 per cent end to involving large wildlife and motor vehicles has increased ±5.8 per cent at the 50 per cent end.