The Charterhouse of the Transfiguration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Latin Mass Society

Ordo 2010 Compiled by Gordon Dimon Principal Master of Ceremonies assisted by William Tomlinson for the Latin Mass Society © The Latin Mass Society The Latin Mass Society 11–13 Macklin Street, London WC2B 5NH Tel: 020 7404 7284 Fax: 020 7831 5585 Email: [email protected] www.latin-mass-society.org INTRODUCTION +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Omnia autem honeste et secundum ordinem fiant. 1 Cor. 14, 40. This liturgical calendar, together with these introductory notes, has been compiled in accordance with the Motu Proprio Rubricarum Instructum issued by Pope B John XXIII on 25th July 1960, the Roman Breviary of 1961 and the Roman Missal of 1962. For the universal calendar that to be found at the beginning of the Roman Breviary and Missal has been used. For the diocesan calendars no such straightforward procedure is possible. The decree of the Sacred Congregation of Rites of 26th July 1960 at paragraph (6) required all diocesan calendars to conform with the new rubrics and be approved by that Congregation. The diocesan calendars in use on 1st January 1961 (the date set for the new rubrics to come into force) were substantially those previously in use but with varying adjustments and presumably as yet to re-approved. Indeed those calendars in use immediately prior to that date were by no means identical to those previously approved by the Congregation, since there had been various changes to the rubrics made by Pope Pius XII. Hence it is not a simple matter to ascertain in complete and exact detail the classifications and dates of all diocesan feasts as they were, or should have been, observed at 1st January 1961. -

Profession Class of 2020 Survey

January 2021 Women and Men Professing Perpetual Vows in Religious Life: The Profession Class of 2020 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Professing Perpetual Vows in Religious Life: The Profession Class of 2020 A Report to the Secretariat of Clergy, Consecrated Life and Vocations United States Conference of Catholic Bishops January 2021 Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Thomas P. Gaunt, SJ, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 6 Institutes Reporting Perpetual Professions .................................................................................... 7 Age of Professed ............................................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to the United States ................................................................. 9 Race and Ethnic Background......................................................................................................... 10 Family Background ....................................................................................................................... -

The Profession Class of 2015

January 2016 New Sisters and Brothers Professing Perpetual Vows in Religious Life: The Profession Class of 2015 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC New Sisters and Brothers Professing Perpetual Vows in Religious Life: The Profession Class of 2015 A Report to the Secretariat of Clergy, Consecrated Life and Vocations United States Conference of Catholic Bishops January 2016 Mary L. Gautier, Ph.D. Thomas P. Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Major Findings ............................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Institutes Reporting Perpetual Professions ..................................................................................... 6 Age of Professed ............................................................................................................................. 7 Race and Ethnic Background .......................................................................................................... 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to United States ....................................................................... 9 Family Background ...................................................................................................................... -

Chinese Catholic Nuns and the Organization of Religious Life in Contemporary China

religions Article Chinese Catholic Nuns and the Organization of Religious Life in Contemporary China Michel Chambon Anthropology Department, Hanover College, Hanover, IN 47243, USA; [email protected] Received: 25 June 2019; Accepted: 19 July 2019; Published: 23 July 2019 Abstract: This article explores the evolution of female religious life within the Catholic Church in China today. Through ethnographic observation, it establishes a spectrum of practices between two main traditions, namely the antique beatas and the modern missionary congregations. The article argues that Chinese nuns create forms of religious life that are quite distinct from more universal Catholic standards: their congregations are always diocesan and involved in multiple forms of apostolate. Despite the little attention they receive, Chinese nuns demonstrate how Chinese Catholics are creative in their appropriation of Christian traditions and their response to social and economic changes. Keywords: christianity in China; catholicism; religious life; gender studies Surveys from 2015 suggest that in the People’s Republic of China, there are 3170 Catholic religious women who belong to 87 registered religious congregations, while 1400 women belong to 37 unregistered ones.1 Thus, there are approximately 4570 Catholics nuns in China, for a general Catholic population that fluctuates between eight to ten million. However, little is known about these women and their forms of religious life, the challenges of their lifestyle, and their current difficulties. Who are those women? How does their religious life manifest and evolve within a rapidly changing Chinese society? What do they tell us about the Catholic Church in China? This paper explores the various forms of religious life in Catholic China to understand how Chinese women appropriate and translate Catholic religious ideals. -

Women and Men Entering Religious Life: the Entrance Class of 2018

February 2019 Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 February 2019 Mary L. Gautier, Ph.D. Hellen A. Bandiho, STH, Ed.D. Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Characteristics of Responding Institutes and Their Entrants Institutes Reporting New Entrants in 2018 ..................................................................................... 7 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Age of the Entrance Class of 2018 ................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to United States ....................................................................... 9 Race and Ethnic Background ........................................................................................................ 10 Religious Background .................................................................................................................. -

A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St

Clemson University TigerPrints Master of Architecture Terminal Projects Non-thesis final projects 12-1986 A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield ounC ty, South Carolina Timothy Lee Maguire Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp Recommended Citation Maguire, Timothy Lee, "A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield County, South Carolina" (1986). Master of Architecture Terminal Projects. 26. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp/26 This Terminal Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Non-thesis final projects at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Architecture Terminal Projects by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MONASTERY FOR THE BROTHERS OF THE ORDER OF CISTERCIANS OF THE STRICT OBSERVANCE OF THE RULE OF ST. BENEDICT. Fairfield County, South Carolina A terminal project presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University in partial fulfillment for the professional degree Master of Architecture. Timothy Lee Maguire December 1986 Peter R. Lee e Id Wa er Committee Chairman Committee Member JI shimoto Ken th Russo ommittee Member Head, Architectural Studies Eve yn C. Voelker Ja Committee Member De of Architecture • ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . J Special thanks to Professor Peter Lee for his criticism throughout this project. Special thanks also to Dale Hutton. And a hearty thanks to: Roy Smith Becky Wiegman Vince Wiegman Bob Tallarico Matthew Rice Bill Cheney Binford Jennings Tim Brown Thomas Merton DEDICATION . -

Proquest Dissertations

Readers, Sanctity, and History in Early Modern Spain Pedro de Ribadeneyra, the Flos sanctorum, and Catholic Community by Jonathan Edward Greenwood A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2011 Jonathan Edward Greenwood Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your rile Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83071-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83071-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land The maronite church of Our Lady of Annunciation in Nazareth Deacon Habib Sandy from Haifa, in Israel, presents in this article one of the Catholic communities of the Holy Land, the Maronites. The Maronite Church was founded between the late 4th and early 5th century in Antioch (in the north of present-day Syria). Its founder, St. Maron, was a monk around whom a community began to grow. Over the centuries, the Maronite Church was the only Eastern Church to always be in full communion of faith with the Apostolic See of Rome. This is a Catholic Eastern Rite (Syrian-Antiochian). Today, there are about three million Maronites worldwide, including nearly a million in Lebanon. Present times are particularly severe for Eastern Christians. While we are monitoring the situation in Syria and Iraq on a daily basis, we are very concerned about the situation of Christians in other countries like Libya and Egypt. It’s true that the situation of Christians in the Holy Land is acceptable in terms of safety, however, there is cause for concern given the events that took place against Churches and monasteries, and the recent fire, an act committed against the Tabgha Monastery on the Sea of Galilee. Unfortunately in Israeli society there are some Jewish fanatics, encouraged by figures such as Bentsi Gopstein declaring his animosity against Christians and calling his followers to eradicate all that is not Jewish in the Holy Land. This last statement is especially serious and threatens the Christian presence which makes up only 2% of the population in Israel and Palestine. -

Frederica Law Became First “Sister of Color” of the Missionary Franciscans

Thursday, February 5, 2004 FEATURE Southern Cross,Page 3 Frederica Law became first “sister of color” of the Missionary Franciscans of the Immaculate Conception hough life was somewhat austere at the Industrial School for Colored Children at Harrisonville Tnear Augusta, many of the pupils who attended the Franciscan Sisters’ boarding school there later remembered it with affection. Frederica Law, one of the students who shared the sisters’ Spartan life and living conditions at the school, was so impressed by her teachers’ efforts that she went on to join their order. Said by one source to have been Articles of Agreement born into slavery, Frederica Law The sisters’ duties at the boarding school of Savannah ventured to included more than teaching. They were to . Harrisonville in the late repair the ramshackle buildings, till the soil and 1870s to study under Mother milk a cow owned by the community. Mary Ignatius Hayes, Somewhere—between farm upkeep and mainte- foundress of the Missionary nance—they were to find time and energy to Franciscan Sisters of the teach the young girls attending their boarding Immaculate Conception. school, among whom was future Franciscan Fre- In the Shadow of His Wings In the Shadow English by birth and former- derica Law. The children’s daily regimen at the , Rita H. DeLorme OSF ly an Anglican nun, Mother boarding school was set out in the “Articles of Ignatius (nee Elizabeth Hayes) converted to Agreement” written by Bishop Gross and signed Catholicism, embraced the penitential life style by Mother Ignatius. Students were to attend of Saint Francis and—founding her own order— daily Mass, followed by instruction in household took a vow of dedication to the foreign missions duties such as washing, ironing, cooking and in addition to vows of poverty, chastity and obe- mending, which—in Bishop Gross’ words— dience. -

The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses During the Middle Ages

Geography and circulation of artistic models The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses during the Middle Ages Cristina DAGALITA ABSTRACT In 1084, Bruno of Cologne established the Grande Chartreuse in the Alps, a monastery promoting hermitic solitude. Other charterhouses were founded beginning in the twelfth century. Over time, this community distinguished itself through the ideal purity of its contemplative life. Kings, princes, bishops, and popes built charterhouses in a number of European countries. As a result, and in contradiction with their initial calling, Carthusians drew closer to cities and began to welcome within their monasteries many works of art, which present similarities that constitute the identity of Carthusians across borders. Jean de Marville and Claus Sluter, Portal of the Chartreuse de Champmol monastery church, 1386-1401 The founding of the Grande Chartreuse in 1084 near Grenoble took place within a context of monastic reform, marked by a return to more strict observance. Bruno, a former teacher at the cathedral school of Reims, instilled a new way of life there, which was original in that it tempered hermitic existence with moments of collective celebration. Monks lived there in silence, withdrawn in cells arranged around a large cloister. A second, smaller cloister connected conventual buildings, the church, refectory, and chapter room. In the early twelfth century, many communities of monks asked to follow the customs of the Carthusians, and a monastic order was established in 1155. The Carthusians, whose calling is to devote themselves to contemplative exercises based on reading, meditation, and prayer, in an effort to draw as close to the divine world as possible, quickly aroused the interest of monarchs. -

Into Great Silence Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Into Great Silence Discussion Guide Director: Philip Gröning Year: 2005 Time: 169 min You might know this director from: The Policeman’s Wife (2013) Into Great Silence Love, Money, Love (2000) Philosophie (1998) Die Terroristen! (1992) Sommer (1988) FILM SUMMARY In 1984, director Philip Gröning wrote to the Carthusian monks with a proposal to film a documentary on their unique life of secluded spirituality at the magnificently austere Grande Chartreuse monastery, located deep in the remoteness of the French Alps. Sixteen years later, he received an unlikely reply in which he was invited to film if he was still interested. Ordinarily visitors are not permitted at the monastery, so Gröning accepted under the stringent terms that he would live and work as the monks do, in silence, filming only in his free time. Over a six month period, the director filmed the daily routine of the monks as they live by the Carthusian statutes, which calls for the solitary contemplation of the holy in order to unite one’s life to charity and purity of heart. Devout in this endeavor, each of these men spend their days studying scripture and praying in the seclusion of their own living quarters, only venturing out to complete their portion of the daily chores or to convene for communal worship. Though they appear grateful for their asceticly spiritual lifestyle, to the outside onlooker it may appear more an exercise in mental endurance than a modus of divine deliverance. Bathed in natural light and the reverberating hymns that provide a haunting aural counterbalance to the overbearing silence that pervades the film, Gröning’s documentation of the Carthusians is an entrancing meditation on time, devotion, faith and contemplation itself. -

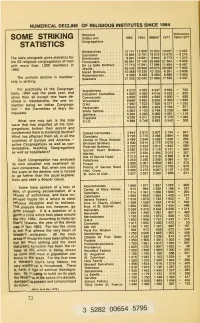

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ...