CATALONIA BACKGROUND INFORMATION [SERIES E / 2013 / 6.1 / EN] Date: 02/07/2013 Author: Michael Keating*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Self-Determination in Times of Shared Sovereignty: Goals and Principles from Catalonia to Europe in the 21St Century

Informe National Self-determination in Times of Shared Sovereignty: Goals and Principles from Catalonia to Europe in the 21st Century AUTHOR: Simon Toubeau PEER REVIEWER: Pere Almeda Aquest informe forma part del programa Llegat Pasqual Maragall que rep el suport de: Contents Part I. The Sources of Deadlock 1. The Ambiguity of Sovereignty 2. Conflicting Claims to National Sovereignty 3. National Minorities have no Right to Self-determination 4. The Persistence of Claims to National Self-Determination 5. The Difficulties of Accommodating Multiple Identities 6. National Self-Determination is equated with Secession 7. Domestic Consent as the Condition for Recognition 8. Protecting the Constitutional Identity of EU Member-States Part II. Scenarios, Proposals and Pathways to Reform 1. An Ambitious Hope: Internal Enlargement in the EU 2. A Bad Alternative: External Secession 3. The Cost of the Status Quo: Informal Politics 4. Dis-Aggregating Sovereignty and Statehood 5. The European Framework: Differentiated Integration 6. A Realistic Proposal (I): Domestic Recognition and Tri-Partite Federalism 7. A Realistic Proposal (II): Functional and Relational Sovereignty in the EU 8. The International Autonomy and Recognition of Non-State Groups Conclusion Bibliography I. The Sources of Deadlock - There is right to national self-determination under international law - collective rights of nation- territorial cultural community (ethnic, linguistic, religious) to choose its own state - not exclusively belonging to nations that form states (e.g decolonization), can be about forging your own state. - about giving consent to form of government - democratic choice via referendum, exercising popular sovereignty - it is about a claim to a collective right about forms of government that are exercised through democratic mechanisms (elections, referendums). -

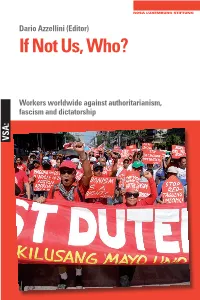

If Not Us, Who?

Dario Azzellini (Editor) If Not Us, Who? Workers worldwide against authoritarianism, fascism and dictatorship VSA: Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships The Editor Dario Azzellini is Professor of Development Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas in Mexico, and visiting scholar at Cornell University in the USA. He has conducted research into social transformation processes for more than 25 years. His primary research interests are industrial sociol- ogy and the sociology of labour, local and workers’ self-management, and so- cial movements and protest, with a focus on South America and Europe. He has published more than 20 books, 11 films, and a multitude of academic ar- ticles, many of which have been translated into a variety of languages. Among them are Vom Protest zum sozialen Prozess: Betriebsbesetzungen und Arbei ten in Selbstverwaltung (VSA 2018) and The Class Strikes Back: SelfOrganised Workers’ Struggles in the TwentyFirst Century (Haymarket 2019). Further in- formation can be found at www.azzellini.net. Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships A publication by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de www.rosalux.de This publication was financially supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung with funds from the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) of the Federal Republic of Germany. The publishers are solely respon- sible for the content of this publication; the opinions presented here do not reflect the position of the funders. Translations into English: Adrian Wilding (chapter 2) Translations by Gegensatz Translation Collective: Markus Fiebig (chapter 30), Louise Pain (chapter 1/4/21/28/29, CVs, cover text) Translation copy editing: Marty Hiatt English copy editing: Marty Hiatt Proofreading and editing: Dario Azzellini This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–Non- Commercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License. -

Special Issue Plurinationality, Federalism and Sovereignty in Spain

Annual Review 2 2017 2017 2 ― Journal on Culture, Power and Society Power ― Journal on Culture, Annual Review Special Issue Plurinationality, Federalism and Sovereignty in Spain: at the Crossroads Contributions Igor Calzada; Rafael Castelló; Germà Bel; Toni Rodon and Marc Sanjaume-Calvet; Mariano M. Zamorano; Luis Moreno Special Issue Cultural changes at university institutions: agentification and quality management Contributions Martí Parellada and Montserrat Álvarez; Manuel Pereira-Puga; Javier Paricio; Juan Arturo Rubio; ENG Cristina Sin, Orlanda Tavares and Alberto Amaral; ISSN: 0212-0585 Antonio Ariño; Andrea Moreno and Tatiana Sapena €6.00 Miscellaneous DEBATS — Journal on Culture, Power and Society Annual Review 2 2017 Annual Review, 2 2017 President of the Valencia Provincial Council [Diputació de València] Jorge Rodríguez Gramage Deputy for Culture Xavier Rius i Torres Director of The Institution of Alfonso The Magnanimous: The Valencian Centre for Research and Investigation (IAM–CVEI) [Institut Alfons el Magnànim. Centre Valencià d’Estudis i d’Investigació] Vicent Flor The opinions expressed in papers and other texts published in Debats. Revista de cultura, poder i societat [Debates. Journal on Culture, Power, and Society] are the sole responsibility of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the views ofDebats or IAM–CVEI/the Valencia Provincial Board. The authors undertake to abide by the Journal’s ethical rules and to only submit their own original work, and agree not to send the same manuscripts to other journals and to declare any conflicts of interest that may result from these manuscripts or articles. While Debats does its utmost to ensure good practices in the journal and to detect any bad practices and plagiarism, it shall not be held liable in any way, shape, or form for any disputes that may arise concerning the authorship of the articles and/or papers it publishes. -

Karl Marx and the Iwma Revisited 299 Jürgen Herres

“Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” <UN> Studies in Global Social History Editor Marcel van der Linden (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Sven Beckert (Harvard University, Cambridge, ma, usa) Dirk Hoerder (University of Arizona, Phoenix, ar, usa) Chitra Joshi (Indraprastha College, Delhi University, India) Amarjit Kaur (University of New England, Armidale, Australia) Barbara Weinstein (New York University, New York, ny, usa) volume 29 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/sgsh <UN> “Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” The First International in a Global Perspective Edited by Fabrice Bensimon Quentin Deluermoz Jeanne Moisand leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Cover illustration: Bannière de la Solidarité de Fayt (cover and back). Sources: Cornet Fidèle and Massart Théophile entries in Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier en Belgique en ligne : maitron-en -ligne.univ-paris1.fr. Copyright : Bibliothèque et Archives de l’IEV – Brussels. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bensimon, Fabrice, editor. | Deluermoz, Quentin, editor. | Moisand, Jeanne, 1978- editor. Title: “Arise ye wretched of the earth” : the First International in a global perspective / edited by Fabrice Bensimon, Quentin Deluermoz, Jeanne Moisand. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2018] | Series: Studies in global social history, issn 1874-6705 ; volume 29 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018002194 (print) | LCCN 2018004158 (ebook) | isbn 9789004335462 (E-book) | isbn 9789004335455 (hardback : alk. -

Spatial Justice and Geographic Scales Introduction a Textbook Case

07/2018 Spatial Justice and Geographic Scales Bernard Bret Translation : Laurent Chauvet Introduction This paper questions spatial justice as conceived in the complexity of a world where geographic scales interfere with one another and link facts produced globally. Because technological advances reduce distances, and because History modifies the politico-administrative network as well as the hierarchy of political territories, we must see these scales not as natural data, but as social constructs that transform over time. Under these conditions, what does a change in geographic scales mean? Is it simply a change in what is being focused on, making it possible to locate, in a reduced space, details that could not otherwise be seen in a wider visual field or, conversely, to sacrifice the details so as to benefit from an overall view? In photography, the term resolution is used to signify the fineness of the grain, and therefore the precision of the lines. However, the heuristic virtue of a multi-scalar approach is not bound to the quality of the description. Similar to where a photo of what is very small – the image given by a microscope – or very large – that given by a telescope – brings out realities that are invisible to the eye, the variations of geographic scales do not simply contextualise what could already be seen. They reveal new explanatory factors as well as new social actors. As such, a multi-scalar approach is less a process of exposure than a research method to explore and decrypt the complexity of reality. It is necessary to understand the imbrication of geographic scales in order to grasp what spatial justice is. -

Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction Within a Divided Catalonia

genealogy Article Parochial Linguistic Education: Patterns of an Enduring Friction within a Divided Catalonia Josep Maria Oller 1,*, Albert Satorra 2 and Adolf Tobeña 3 1 Department of Genetics, Microbiology and Statistics, University of Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 2 Department of Economics and Business, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 08005 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychiatry and Forensic Medicine, Institute of Neurosciences, Universitat Autònoma Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Amid the tensions created by the secession push in Catalonia (Spain), an important conflicting issue has been the “immersion linguistic educational system”, in which the Catalan language has precedence throughout all of the primary and secondary school curricula. Here, we present an analysis of a survey (n = 1002) addressing features of linguistic and political opinion profiles with reference to the mother language and feelings of national identity. The results show that the mother language is a factor that differentiated the participants in terms of common linguistic uses and opinions about the “immersion educational system”. These results were confirmed when segmenting respondents via their feelings of national self-identification. The most distinctive political opinions consisted of either asserting or denying the damage to social harmony produced by the secession campaign. Overall, the findings show that a major fraction of the Catalonian citizenry is subjected to an education system that does not meet their linguistic preferences. We discuss these findings, connecting them to an ethnolinguistic divide based mainly on mother language (Catalan vs. Spanish) and family origin—a complex frontier that has become the main factor determining Citation: Oller, Josep Maria, Albert alignment during the ongoing political conflict. -

Inside Spain Nr 146 19 December 2017 - 22 January 2018

Inside Spain Nr 146 19 December 2017 - 22 January 2018 William Chislett Summary Spain to boost defence spending and send more troops abroad. New Catalan parliament’s pro-independence speaker calls for deposed Puigdemont to be re-elected the region’s Premier. Catalan electoral success propels Ciudadanos towards national victory. Madrid fails to fully implement any of the Council of Europe’s anti-corruption measures. Spanish-built high-speed train in Saudi Arabia successfully completes first test run. Foreign Policy Spain to boost defence spending and send more troops abroad The government told NATO it would increase defence spending by more than 80% over the next seven years to around €18 billion, but it would still be below the guideline of 2% of GDP that NATO’s 28 members agreed for 2024 at their 2014 summit in Wales. Spain’s current military spending of 0.92% of GDP is among the lowest (see Figure 1). Only five countries meet the 2% target: the US, UK, Greece, Estonia and Poland. Figure 1. Defence expenditure as a share of GDP (%) (1) % of GDP US 3.58 UK 2.14 NATO guideline 2.00 France 1.79 Germany 1.22 Italy 1.13 Spain 0.92 Luxembourg 0.44 (1) Estimates for 2017. Source: NATO. 1 Inside Spain Nr 146 19 December 2017 - 22 January 2018 María Dolores de Cospedal, the Defence Minister, said more troops would be sent abroad to participate in international missions. The number in Mali will rise by 152, those in Afghanistan by 95 and in Iraq by 30. -

Learning the Lessons of the Catalan Rebellion As an 'Event'

LEARNING THE LESSONS OF THE CATALAN REBELLION AS AN ‘EVENT’ Ramón Grosfoguel What happened in Catalonia on October 1 and 3118 can be described as what the philosopher Alain Badiou calls the event, what the Marxist Walter Benjamin refers to as messianic time, and what indigenous Quechua people in Latin America call Pachakuti. These concepts all put a name to the eruption of something unexpected in a situation that interrupts the continuity, or the logic of reproduction in the structure of domination. 244 The structure of domination has a logic of monotonous- continuous reproduction until a social movement that nobody expects abruptly bursts into it, like, for example, a popular uprising or a mass popular reaction. These events are ephem- eral, they are never lasting. To endure, they must be have a political response that produces a genuinely innovative political discourse; one that can account for the new “subjectivity” and “truth” produced by the event. To this end the entire political discourse must be renewed; it must be updated in accordance with the new subjectivity that the event produced for people. The question to ask yourself about Catalonia is: What is the political response to October 1 and October 3? Opening a 118.October 3 refers to the general strike that saw more than two million people on the streets. debate about this is of utmost importance. There, in Catalonia something happened that had not been foreseen: a people emerged who were willing to defend their sovereignty, their right to decide, and their right to self-determination with their very bodies. -

Satire in the Service of History. on the Phenomenon of Tabarnia in Catalonia1

STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 22/2020 ISSN 2082-5951 DOI 10.14746/seg.2020.22.5 Filip Kubiaczyk (Poznań-Gniezno) https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4124-6480 SATIRE IN THE SERVICE OF HISTORY. ON THE PHENOMENON OF TABARNIA IN CATALONIA1 Abstract The paper analyzes the phenomenon of Tabarnia, a grassroots social movement aiming to ex- pose and counter the absurdities of the Catalan independence nationalism. The adherents of Tabar- nia employ irony, situational humour, performance and historical re-enactment to ridicule and neu- tralize the nationalist discourse. Key words Tabarnia, Catalonia, Tabarnia is not Catalonia, Albert Boadella, satire, irony, Catalonian na- tionalism, tabarneses, Tabarnexit There can be no doubt that Spain’s greatest political problem today is the sit- uation in Catalonia which, governed by the nationalist faction, clearly strives for secession. The Spanish State faces a serious structural problem, which stems from the traditional conflict between unionists and federalists. Although the Consti- tution of Spain of 1978 affirms it to be a united state based on autonomies, the example of Catalonia demonstrates that the issue persists. As a by-product of that process, a grassroots social movement emerged in Catalonia, whose goal is to counter the nationalist project by ridicule and tongue-in-cheek mimicking. Tabarnia, as the movement is called, has not only attracted numerous Catalans 1 This paper has been developed as part of the National Centre for Science grant (MINIATURA 1); no. 2017/01/X/HS3/00689. 90 Filip Kubiaczyk but also Spaniards. What started as a joke, transformed with time into a pow- erful social weapon, which stirred up nervous reactions among the nationalists. -

Identity and Nation in 21St Century Catalonia

Identity and Nation in 21st Century Catalonia Identity and Nation in 21st Century Catalonia: El Procés Edited by Steven Byrne Identity and Nation in 21st Century Catalonia: El Procés Edited by Steven Byrne This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Steven Byrne and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-7270-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-7270-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures.......................................................................................... viii List of Tables ............................................................................................. ix List of Images ............................................................................................. x Notes on Contributors ................................................................................ xi Acknowledgements ................................................................................ xvii Introduction ........................................................................................... xviii Steven Byrne Section One: Catalonia and Secessionism: Understanding Ongoing -

Preston, Paul, the Coming of the Spanish Civil War: Reform, Reaction and Revolution in the Second

THE COMING OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR The breakdown of democracy in Spain in the 1930s resulted in a torrent of political and military violence. In this thoroughly revised edition of his classic text, Paul Preston provides a deeply disturbing explanation of the democratic collapse, coherently and excitingly outlining the social and economic background. Spain was a backward agricultural country divided by the most brutal economic inequalities. The coming of the Second Republic in April 1931 was greeted by the Left as an opportunity to reform Spain’s antiquated social structure. Over the next two years, the Socialist members of a Republican—Socialist coalition pushed for reforms to alleviate the day-to- day misery of the great southern army of landless labourers. Paul Preston shows how the political activities of the Right, legal and conspiratorial, between 1931 and 1936, as well as the subsequent Nationalist war effort, were primarily a response to these reforming ambitions of the Left. His principal argument is that, although the Spanish Civil War encompassed many separate conflicts, the main cause of the breakdown of the Second Republic was the struggle between Socialists and the legalist Right to impose their respective views of social organisation on Spain by means of their control of the apparatus of state. The incompatible interests represented by these two mass parliamentary parties—those of the landless labourers and big landlords, of industrialists and workers—spilled over into social conflicts which could not be contained within the parliamentary arena. Since the first edition of this book was completed more than fifteen years ago, archives have been opened up, the diaries, letters and memoirs of major protagonists have been published, and there have been innumerable studies of the politics of the Republic, of parties, unions, elections and social conflict, both national and provincial. -

Spain: Works Councils Or Unions?

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Works Councils: Consultation, Representation, and Cooperation in Industrial Relations Volume Author/Editor: Joel Rogers and Wolfgang Streeck Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-72376-3 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/roge95-1 Conference Date: May 13-16, 1992 Publication Date: January 1995 Chapter Title: Spain: Works Councils or Unions? Chapter Author: Modesto Escobar Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11559 Chapter pages in book: (p. 153 - 188) Spain: Works Councils or Unions? Modesto Escobar 6.1 Introduction: Industrial Relations in Spain In Spain works councils are legally defined as unitary bodies for the repre- sentation of workers at the workplace. The law also regulates the existence of union sections inside the firm. In this sense, there is a dual system of worker representation in Spanish labor relations. However, in contrast to many other systems, the "second channel" of interest representation is especially salient in relation to the unions, which control the works councils and implement their policies at the firm level through them. One of the main questions that the Spanish case raises is precisely whether and to what extent it is possible for a union to pursue its policies effectively by means of an institution with union and nonunion duties. Another important question concerns the implications of a council representation system in a country with two main unions divided along ideological and political lines: the socialist Union General de Trabaja- dores (UGT—General Union of Workers) and the communist Comisiones Obreras (CCOO—Workers' Commissions).