Folksongs As an Epistemic Resource: Understanding Bhojpuri Women's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Diaspora and Sundar Popo's Chutney Lyrics As Indo

Mohabir, R 2019 Chutneyed Poetics: Reading Diaspora and Sundar Popo’s Chutney Lyrics as Indo-Caribbean Postcolonial Literature. Anthurium, 15(1): 4, 1–17. ARTICLE Chutneyed Poetics: Reading Diaspora and Sundar Popo’s Chutney Lyrics as Indo-Caribbean Postcolonial Literature Rajiv Mohabir Auburn University, US [email protected] It is my intent for these new readings of Sundar Popo’s song lyrics to not only challenge modern epistemic violence perpetrated against the deemed frivolity of Chutney (as a genre’s) lyrics, but also to utilize the original texts to understand these songs as an essential postcolonial Indo-Caribbean literature. Since the archive of Caribbean literature includes predominantly English, Spanish, French, and various nation languages, I posit the inclusion of Caribbean Hindi as a neglected archive is worth exploring given its rich significations as literature. I engage chutney music, a form of popular music, as poetry to illustrate the construction of Indo-Caribbean identity through the linguistic and poetic features of its lyrics as a cultural production that are created by the syncretisms of the Caribbean. This paper is written in four sections: 1. A Chutneyed Diaspora, 2. Methods and Approach, 3. Chutney Translation and Analysis: Bends Towards Meaning and 4. Diaspora as Chutney. The first section provides a historical stage for the emergence of Chutney music, concentrating on an introduction to the trends of its study by contemporary ethnomusicologists. The second section introduces my own approach to the study of oral traditions as literature and my engagement with my subjective postcolonial positioning as an individual of Indo-Caribbean origin. -

Bhojpuri Media at a Crossroads Madhusri Shrivastava, [email protected]

Sleaze, Slur… and the Search for a Sanitized Identity: Bhojpuri Media at a Crossroads Madhusri Shrivastava, [email protected] Volume 5.1 (2015) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2015.130 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract This article offers perspectives on those who control the Bhojpuri media industry in Mumbai, India, and delimit what is to be shown. Bhojpuri is a dialect of Hindi spoken in parts of the north Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The influx of migrants from these regions to different parts of India has led to a resurgence of interest in the Bhojpuri media, and has drawn fly-by-night operators to the industry. To cater to the migrants’ needs, ribald action romances are produced; but this very bawdiness hamstrings attempts to widen the audience base. The article examines the issues that plague the industry, and explores the ways in which the industry is struggling to carve a sanitized, yet distinctive identity. Keywords: Bhojpuri; media industry; ribald; sanitized; migrants New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Sleaze, Slur… and the Search for a Sanitized Identity: Bhojpuri Media at a Crossroads Madhusri Shrivastava This article seeks to explore the perspective of those who control the Bhojpuri culture industry, and delimit what is to be shown. It is part of a comprehensive research on the manner in which Bhojpuri media help north Indian migrants in Mumbai remain anchored to their traditions and values. -

3-Peter Manuel.Pmd

Man In India, 93 (1) : 45-56 © Serials Publications RETENTION AND INVENTION IN BHOJPURI DIASPORIC MUSIC CULTURE: PERSPECTIVES FROM THE CARIBBEAN, INDIA, AND FIJI Peter Manuel Bhojpuri diasporic culture, especially as constituted in the Caribbean, Fiji, and secondary diasporic sites, exhibits striking consistency in its patterns of neo-traditional music making. Based on extensive research in North India and the Caribbean (including Suriname), and with Indo- Fijian communities in the USA, in this paper I explore some of the socio-musical dynamics which have conditioned music culture in the diaspora. I also explore relations of musical genres and entities to their counterparts and sources in the Bhojpuri region. I suggest a categorization of neo-traditional music entities into such groups as: marginal survivals (such as the Caribbean birha style), orthogenetic neo-traditional genres (local-classical music, tassa drumming), and entities which, though derived from India, have declined in that country and became disproportionately more widespread in the diaspora (such as chowtal and the dantal). I suggest ways in which the Bhojpuri diasporic traditional music cultures of Fiji and the Caribbean, though isolated from each other (and from Bhojpuri India), exhibit similar patterns of differentiation from ancestral North Indian Bhojpuri music culture. It has become commonplace to observe that diasporic cultures, rather than constituting miniature or diluted versions of their ancestral homeland counterparts, possess their own independent character, vitality, and legitimacy. In pointing out these distinctive features, scholars and others generally celebrate the syncretic and innovative dynamism of diasporic and border cultures. Hence, for example, chutney- soca is often hailed as a reflection of the more creative and inclusive aspect of Indo-Caribbean music culture, as opposed to genres like birha or chowtal that are merely derivatives of Indian predecessors, or as opposed to local amateur renditions of Bollywood hits. -

Retention and Invention in Bhojpuri Diasporic Music Culture: Perspectives from the Caribbean, India, and Fiji

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2013 Retention and invention in Bhojpuri diasporic music culture: Perspectives from the Caribbean, India, and Fiji Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/23 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 3 PETER MANUEL It has become commonplace to observe that diasporic cultures, rather than constituting miniature or diluted versions of their ancestral homeland counterparts, possess their own independent character, vitality, and legitimacy. In pointing out these distinctive features, scholars and others generally celebrate the syncretic and innovative dynamism of diasporic and border cultures. Hence, for example, chutney-soca is often hailed as a reflection of the more creative and inclusive aspect of Indo-Caribbean music culture, as opposed to genres like birha or chowtal that are merely derivatives of Indian predecessors, or as opposed to local amateur renditions of Bollywood hits. The dynamism of a genre like chutney- soca, and the way in which it makes Indo-Caribbean culture distinctive, are typically seen as located precisely in the way that it embodies creolization, or syncretism with a local non-Indian genre. While not challenging the accuracy or importance of these perspectives, in this paper I wish to focus on the more traditional and neo-traditional stratum of Bhojpuri diasporic music culture in the Caribbean, with passing reference to Indo-Fijian music culture. -

From Cassette Culture to Cyberculture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2014 The Regional North Indian Popular Music Industry in 2014: From Cassette Culture to Cyberculture Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/299 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Popular Music (2014) Volume 33/3. © Cambridge University Press 2014, pp. 389–412 doi:10.1017/S0261143014000592 The regional North Indian popular music industry in 2014: from cassette culture to cyberculture PETER MANUEL Art & Music Department, John Jay College, New York, NY 10018 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article explores the current state of the regional vernacular popular music industry in North India, assessing the changes that have occurred since around 2000 with the advent of digital tech- nologies, including DVD format, and especially the Internet, cellphones and ‘pen-drives’. It provides a cursory overview of the regional music scene as a whole, and then focuses, as a case study, on a particular genre, namely the languriya songs of the Braj region, south of Delhi. It discusses how com- mercial music production is adapting, or failing to adapt, to recent technological developments, and it notes the vigorous and persistent flowering of regional music scenes such as that in the Braj region. In my 1993 book, Cassette Culture: Popular Music and Technology in North India, I endeavoured to present a holistic study of the revolutionary impact of audio cas- settes on vernacular Indian music production, content and consumption during the years around 1990. -

Transnational Chowtal: Bhojpuri Folksong from North India to the Caribbean, Fiji, and Beyond

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2009 Transnational Chowtal: Bhojpuri Folksong from North India to the Caribbean, Fiji, and Beyond Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/308 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Transnational Chowtal: Bhojpuri Folk Song from North India to the Caribbean, Fiji, and Beyond Peter Manuel In mid-February of 2007, I attended some lively sessions of chowtal (Hindi, cautāl), a boisterous Bhojpuri folk song genre, in a Hindu temple in a small town a few hours from Banaras (Varanasi), North India.1 Th e following weekend I was singing chowtal, in an identical style, with an Indo-Guyanese ensemble in Queens, New York City. In the subsequent season of the vernal Holi (Hindi, holī) festival, in March 2008, I found myself singing along with a group of Indo-Fijians in Sacramento, California, as they performed a similar version of one of the same chowtal songs. Despite the nearly identical styles of the three song sessions, they were separated not only by thousands of miles, but more signifi cantly, by the more than 90 years that have elapsed since indentured emigration from the Bhojpuri region ceased. Subsequently, cultural contacts between that region and its diasporic communities in the Caribbean and Fiji became minimal, and those between the latter two sites have been practically nil. -

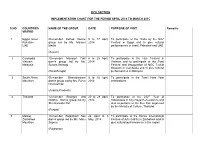

Ocd Section Implementation Chart for the Period April

OCD SECTION IMPLEMENTATION CHART FOR THE PERIOD APRIL 2014 TO MARCH 2015 S.NO. COUNTRIES NAME OF THE GROUP DATE PURPOSE OF VISIT Remarks VISITED 1 Egypt, Israel 06-member Kathak Dance 5 to 17 April, To participate at the “India by the Nile” Palestine group led by Ms. Marami 2014 Festival in Egypt and to give cultural UAE Medhi performances in Israel, Palestine and UAE (Assam) 2 Cambodia 10-member Manipuri Folk 6 to 25 April, To participate in the Hue Festival in Vietnam dance group led by Ms. 2014 Vietnam and to participate at the Food Malaysia Suman Sarawgi Festival and inauguration of MGC Textile Museum in Cambodia and to give cultural (West Bengal) performances in Malaysia 3 South Africa 05-member Bharatnatyam 8 to 18 April, To participate in the Tamil New Year Mauritius dance group led by Ms. Purva 2014 celebrations Dhanashree (Andhra Pradesh) 4 Thailand 12-member Bhangra and 20 to 28 April, To participate at the 232nd Year of Giddha Dance group led by 2014 Rattanakos in City Royal Benevolence and Shri Harinder Pal also to perform at the Fun Fair organized by the Ministry of Culture, Thailand (Punjab) 5 Malawi 10-member Rajasthani folk 24 April to 9 To participate at the Harare International Zimbabwe dance group led by Ms. Moru May, 2014 Festival of Arts (HIFA) in Zimbabwe and to Mauritius Sapera give cultural performances in the region (Rajasthan) 6 Switzerland, 06-member Kathak Dance 12 May to 9 To participate at the Trade Fair in Germany group led by Ms. Rujuta June, 2014 Belgrade and to give cultural Serbia, Soman performances in the region Montenegro Austria, Croatia (Maharashtra) Spain 7 Japan 08-member Kathakali dance 15 May to 1st To participate at the Commemorative China group led by Shri M. -

Kumar, Akshaya (2015) Provincialising Bollywood: Bhojpuri Cinema and the Vernacularisation of North Indian Media. Phd Thesis. Ht

Kumar, Akshaya (2015) Provincialising Bollywood: Bhojpuri cinema and the vernacularisation of North Indian media. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/6520/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Provincialising Bollywood: Bhojpuri Cinema and the Vernacularisation of North Indian Media Akshaya Kumar Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow School of Culture and Creative Arts July 2015 © Akshaya Kumar 2015 Abstract This thesis is an investigation of the explosive growth of Bhojpuri cinema alongside the vernacularisation of north Indian media in the last decade. As these developments take place under the shadow of Bollywood, the thesis also studies the aesthetic, political, and infrastructural nature of the relationship between vernacular media industries – Bhojpuri in particular – and Bollywood. The thesis then argues that Bhojpuri cinema, even as it provincialises Bollywood, aspires to sit beside it instead of displacing it. The outrightly confrontational readings notwithstanding, the thesis grapples with the ways in which the vernacular departs from its corresponding cosmopolitan form and how it negotiates cultural representation as an industry. -

Folksongs As an Epistemic Resource: Understanding Bhojpuri Women's

Public Arguments – 3 Tata Institute of Social Sciences Patna Centre Folksongs as an Epistemic Resource: Understanding Bhojpuri Women’s Articulations of Migration Asha Singh February 2017 Tata Institute of Social Sciences Patna Centre Folksongs as an Epistemic Resource: Understanding Bhojpuri Women’s Articulations of Migration Asha Singh February 2017 Public Arguments Publication: 2017 Publisher: Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Patna Centre Takshila Campus DPS Senior Wing Village: Chandmari, Danapur Cantonment Patna – 801502 (Bihar) INDIA Website: www.tiss.edu e-mail: [email protected] This publication is part of a lecture series on ‘migration’. We express our gratitude to Takshila Educational Society for supporting the lecture series. Folksongs as an Epistemic Resource: Understanding Bhojpuri Women’s Articulations of Migration Asha Singh1 Since centuries, women in Bhojpuri-speaking peasant society of western Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh have been experiencing out-migration of their men. The process of labour out-migration, in Bhojpuri peasant society, marks a creative peak in the history of oral cultural productions (especially folksongs).2 Bhojpuri society is so deeply characterised by migration that it has become a frame of reference for all its cultural formulations. It has produced creative subjects. In Bhojpuri folksongs, the ‘migrant’ and his ‘left-behind wife’ are significant examples of such creative subjects. The latter being the protagonist in most of the Bhojpuri folksongs sung by women and men. This essay is a result of my doctoral work on Bhojpuri women’s folksongs in the context of male out-migration. It captures crucial sociological insights that I gathered in the journey of my studies. -

Indian Folk Music and ‘Tropical Body Language’: the Case of Mauritian Chutney

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Free-Standing Articles | 2011 Indian Folk Music and ‘Tropical Body Language’: The Case of Mauritian Chutney Catherine Servan-Schreiber Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3111 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.3111 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Catherine Servan-Schreiber, « Indian Folk Music and ‘Tropical Body Language’: The Case of Mauritian Chutney », South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], Free-Standing Articles, Online since 24 January 2011, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3111 ; DOI : 10.4000/samaj.3111 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Servan-Schreiber, Catherine (2011) ‘Indian Folk Music and ‘Tropical Body Language’: The Case of Mauritian Chutney’, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal. URL: http://samaj.revues.org/index3111.html To quote a passage, use paragraph (§). Indian Folk Music and ‘Tropical Body Language’: The Case of Mauritian Chutney Catherine Servan-Schreiber Abstract. In Mauritius, the meeting between Indian worlds and Creole worlds, through the migration of the indentured labour which followed the abolition of slavery in 1834, gave birth to a style of music called ‘chutney’. As a result of the African influence on an Indian folk genre, chutney music embodies the transformation of a music for listening into a music for dancing. In this article, the innovations brought into the choreographical dimension of the chutney groups will be taken as a key to understanding the adaptation of Indian rural migrants to a new ‘Indian-oceanic’ way of life through the experience of diaspora. -

PDF Download

International Journal of Education and Social Science Research ISSN 2581-5148 Vol. 3, No. 03; 2020 TOWARDS A SAFEGUARDING CONCEPT OF THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN MAURITIUS Mr Jayganesh DAWOSING Lecturer, Department of Bhojpuri, Folklore and Oral Traditions Mahatma Gandhi Institute (Mauritius) http://dx.doi.org/10.37500/IJESSR.2020.302263 ABSTRACT Recently, the word ‘Heritage’ has become a scholarship field with multiple issues. An integral part of human cultures, heritage interests today both the decision maker, the researcher, the public but also the international organizations. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) inscribed the Bhojpuri folk songs from Mauritius known as “Geet Gawai” to the representative list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in December 2016. Within these two years, this Intangible Heritage, deemed worthy of preservation, is often regarded as traditional culture that reflects the identity of a particular nation or group. This paper is aimed at defining the concept of intangible cultural heritage in the context of safeguarding of Bhojpuri folk songs and its evolution after the inscription in the list of the world Intangible Cultural Heritage. Through documentary research on the various ways to preserve heritage and empirical data collected in ethnographic research, both related to the context of the preservation of intangible heritage in Mauritius, we came to findings that reveal certain problems involving the transformation of the performance of the Mauritian Geet Gawai as an alternative to the preservation of local cultural traditions. Furthermore, idealization of certain forms and periods of heritage conflicts with the spirit and principles of the Convention. KEYWORDS: Safeguarding, Intangible Cultural Heritage, Bhojpuri, Geet-Gawai, Evolution, Traditions. -

Annexure-I Implementation Chart for the Period April

ANNEXURE-I IMPLEMENTATION CHART FOR THE PERIOD APRIL 2014 TO MARCH 2015 S. COUNTRIES NAME OF THE GROUP DATE PURPOSE OF VISIT Remarks NO. VISITED 1 Egypt, Israel 06-member Kathak Dance group led by Ms. 5 to 17 April, To participate at the “India by the Nile” Festival in Egypt and Palestine Marami Medhi 2014 to give cultural performances in Israel, Palestine and UAE UAE (Assam) 2 Cambodia 10-member Manipuri Folk dance group led by 6 to 25 April, To participate in the Hue Festival in Vietnam and to participate Vietnam Ms. Suman Sarawgi 2014 at the Food Festival and inauguration of MGC Textile Museum Malaysia (West Bengal) in Cambodia and to give cultural performances in Malaysia 3 South Africa 05-member Bharatnatyam dance group led by 8 to 18 April, To participate in the Tamil New Year celebrations Mauritius Ms. Purva Dhanashree 2014 (Andhra Pradesh) 4 Thailand 12-member Bhangra and Giddha Dance group 20 to 28 April, To participate at the 232nd Year of Rattanakos in City Royal led by Shri Harinder Pal (Punjab) 2014 Benevolence and also to perform at the Fun Fair organized by the Ministry of Culture, Thailand 5 Malawi 10-member Rajasthani folk dance group led by 24 April to 9 To participate at the Harare International Festival of Arts Zimbabwe Ms. Moru Sapera May, 2014 (HIFA) in Zimbabwe and to give cultural performances in the Mauritius (Rajasthan) region 6 Switzerland, 06-member Kathak Dance group led by Ms. 12 May to 9 To participate at the Trade Fair in Belgrade and to give cultural Germany Rujuta Soman June, 2014 performances in the region Serbia, Montenegro Austria, Croatia (Maharashtra) Spain 7 Japan 08-member Kathakali dance group led by Shri 15 May to 1st To participate at the Commemorative Lecture and music China M.