Ecology and Management of Pinyon-Juniper Communities Within the Interior West: Overview of the "Resource Values Session" of the Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juniperus Communis L.) Essential Oil

Antioxidants 2014, 3, 81-98; doi:10.3390/antiox3010081 OPEN ACCESS antioxidants ISSN 2076-3921 www.mdpi.com/journal/antioxidants Article Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Juniper Berry (Juniperus communis L.) Essential Oil. Action of the Essential Oil on the Antioxidant Protection of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Model Organism Martina Höferl 1,*, Ivanka Stoilova 2, Erich Schmidt 1, Jürgen Wanner 3, Leopold Jirovetz 1, Dora Trifonova 2, Lutsian Krastev 4 and Albert Krastanov 2 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Division of Clinical Pharmacy and Diagnostics, University of Vienna, Vienna 1090, Austria; E-Mails: [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (L.J.) 2 Department Biotechnology, University of Food Technologies, Plovdiv 4002, Bulgaria; E-Mails: [email protected] (I.S.); [email protected] (D.T.); [email protected] (A.K.) 3 Kurt Kitzing Co., Wallerstein 86757, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 University Laboratory for Food Analyses, University of Food Technologies, Plovdiv 4002, Bulgaria; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-1-4277-55555; Fax: +43-1-4277-855555. Received: 11 December 2013; in revised form: 26 January 2014 / Accepted: 28 January 2014 / Published: 24 February 2014 Abstract: The essential oil of juniper berries (Juniperus communis L., Cupressaceae) is traditionally used for medicinal and flavoring purposes. As elucidated by gas chromatography/flame ionization detector (GC/FID) and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS methods), the juniper berry oil from Bulgaria is largely comprised of monoterpene hydrocarbons such as α-pinene (51.4%), myrcene (8.3%), sabinene (5.8%), limonene (5.1%) and β-pinene (5.0%). -

A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus Communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine

© 2021 JETIR March 2021, Volume 8, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine. A Review * Dr. Aafiya Nargis 1, Dr. Ansari Bilquees Mohammad Yunus 2, Dr. Sharique Zohaib 3, Dr. Qutbuddin Shaikh 4, Dr. Naeem Ahmed Shaikh 5 *1 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Niswan wa Qabalat, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon 2 Associate professor, Dept. Tashreeh ul Badan, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon. 3 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Saidla, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Manssoora, Malegaon 4 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Tahaffuzi wa Samaji Tibb, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. 5 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Ain, Uzn, Anf, Halaq wa Asnan, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. Abstract:- Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are 훼-pinene, 훽-pinene, apigenin, sabinene, 훽-sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others Juniperus communis L. (Abhal) is an evergreen aromatic shrub with high therapeutic potential in human diseases. This plant is loaded with nutrition and is rich in aromatic oils and their concentration differ in different parts of the plant (berries, leaves, aerial parts, and root). The fruit berries contain essential oil, invert sugars, resin, catechin , organic acid, terpenic acids, leucoanthocyanidin besides bitter compound (Juniperine), flavonoids, tannins, gums, lignins, wax, etc. -

Tips for Cooking with Juniper Hunt Country Marinade

Recipes Tips for Cooking with Juniper • Juniper berries can be used fresh and are commonly sold dried as well. • Add juniper berries to brines and dry rubs for turkey, pork, beef, and wild game. • Berries are typically crushed before added to marinades and sauces. Hunt Country Marinade ¾ cup Cabernet Sauvignon or other dry red wine 3 large garlic cloves, minced ¼ cup balsamic vinegar 3 2x1-inch strips orange peel (orange part only) 3 tablespoons olive oil 3 2x1-inch strips lemon peel (yellow part only) 2 tablespoons unsulfured (light) molasses 8 whole cloves 2 tablespoons chopped fresh thyme or 2 8 whole black peppercorns teaspoons dried 2 bay leaves, broken in half 2 tablespoons chopped fresh rosemary or 2 ¾ teaspoon sa teaspoons dried 1 tablespoon crushed juniper berries or 2 tablespoons gin Mix all ingredients in a medium bowl. (Can be made 2 days ahead. Cover; chill.) Marinate poultry 2 to 4 hours and meat 6 to 12 hours in refrigerator. Drain marinade into saucepan. Boil 1 minute. Pat meat or poultry dry. Grill, basting occasionally with marinade. — Bon Appetit July 1995 via epicurious.com ©2016 by The Herb Society of America www.herbsociety.org 440-256-0514 9019 Kirtland Chardon Road, Kirtland, OH 44094 Recipes Pecan-Crusted Beef Tenderloin with Juniper Jus Two 2 ½ - pound well-trimmed center-cut 1 cup pecans, very finely chopped beef tenderloins, not tied 3 shallots, thinly sliced Salt and freshly ground pepper 1 carrot, thinly sliced 4 tablespoons unsalted butter 1 tablespoon tomato paste 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil 2 teaspoons dried juniper berries, crushed ¼ cup ketchup 1 ½ cups full-bodied red wine, such as Syrah ¼ cup Dijon mustard 1 cup beef demiglace (see Note) 4 large egg yolks Preheat the oven to 425°F. -

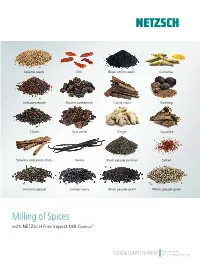

Milling of Spices with NETZSCH Impact Mills Condux

Sesame seeds Chili Black onion seeds Curcuma Sichuan pepper Brown cardamom Cassia sticks Nutmeg Cloves Star anise Ginger Liquorice Srilanka cinnamon sticks Vanila Black pepper powder Safran Jamaica pepper Juniper berry Black pepper grain White pepper grain Milling of Spices with NETZSCH Fine Impact Mill CONDUX® a Business Field of FOOD & CONFECTIONERY NETZSCH Grinding & Dispersing Milling of Spices with Fine Impact Mill CONDUX® Processing and refi ning are the actual tasks of the spice industry – a product which is “suitable for consumption” must be manufac- tured from the raw spices. One of the main tasks is the grinding of the raw materials. As the fl avouring components – mainly essential oils – are very volatile, a particularly gentle grinding procedure must be used. This task can be carried out easily using the NETZSCH Fine Impact Mill CONDUX®. Combine your excellent spices with our high quality machines and your success will be inevitable! NETZSCH Fine Impact Mill CONDUX® 680 Processing Spices Spices enrich our life with taste. It is a long way Your Advantages at a Glance from the seed to the ready packed powder in our kitchen. To preserve a maximum of taste a Impact mill for various types of lot of processes must be considered. ∙ spices Various grinding tools One key process in this procedure is the ∙ High fineness particle size reduction. A low particle size ∙ Low temperatures distribution means great taste and beautiful ∙ Sturdy design color. However, if the temperature increase ∙ Easy to clean during processing is too great, the taste and ∙ color of the spice su er. Especially for such sensitive products we have developed some special machines, which enable high grinding e ciency combined with a very low temperature increase. -

Combining Herbs and Essential Oils This Presentation Explores How

Hawthorn University Holistic Health and Nutrition Webinar Series 2017 www.hawthornuniversity.org Presented by David Crow, L.Ac. Combining Herbs and Essential Oils This presentation explores how essential oils and aromatherapy can be integrated with herbal treatments for added therapeutic effects and benefits. It explores which essential oils can be safely combined, and how, with herbs according to therapeutic functions: ) Expectorant, mucolytic, decongestant and antitussive herbs ) Nervine relaxant, sedative and anxiolytic herbs ) Demulcent herbs ) Anti-spasmotic and analgesic herbs ) Antimicrobial herbs ) Cholagogue and laxative herbs ) Immune modulating and immune stimulating herbs ) Adaptogen, trophorestorative and neuroendocrine regulating herbs ) Antiinflammatory herbs ) Emmenagogue and uterine tonic herbs Learning Objectives: ) When and how essential oils and aromatherapy are a primary, adjunct or contraindicated treatment ) To understand the compatibility or lack of compatibility of specific groups and species of essential oils and specific groups and species of herbs ) Simple combinations of herbs and essential oils for specific therapeutic benefits Introduction ) General suggestions for how to use safely therapeutic groups of essential oils in combinations with groups of herbs. ) Does not give detailed methods of use of the oils. ) Does not give any specific dosages or uses of herbs. ) Please do not use herbs without studying them in detail. ) Please use essential oils according to safe methods of applications ) Do not take internally ) Do not apply undiluted to the skin Difficulties classifying essential oils into therapeutic categories Where do the claims about therapeutic actions of essential oils come from? 1. Empirical evidence from long history of use of aromatic plants 2. Modern scientific studies 3. Claims made about essential oils through MLM companies and spread on the internet Many claims about the functions of essential oils are not substantiated or established. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0295860 A1 DAGHER Et Al

US 2016O295860A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0295860 A1 DAGHER et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 13, 2016 (54) A NOVEL COMPOSITION AND METHOD OF AOIN 25/00 (2006.01) USE TO CONTROL PATHOGENS AND AOIN 31/02 (2006.01) PREVENT DISEASES IN SEEDS (52) U.S. Cl. CPC ............... A0IN 37/16 (2013.01); A0IN 25/00 (71) Applicant: AGRI-NEO INC., Toronto (CA) (2013.01): A0IN 31/02 (2013.01); A23B 9/26 (2013.01); A23B 9/30 (2013.01); A23V (72) Inventors: Fadi DAGHER, Laval (CA); Nicholas 2002/00 (2013.01) DILLON, Toronto (CA); Kenneth Sherman UNGAR, Scarborough (CA) (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: AGRI-NEO INC., Toronto, ON (CA) The invention relates to a composition of water-soluble ingredients (CWSI) which when solubilized in water (W) (21) Appl. No.: 15/038,211 and either in the presence of a wetting agent and/or in the presence of at least one agriculturally acceptable solvent, (22) PCT Fed: Nov. 13, 2014 forms a synergistic composition useful for the control of (86) PCT No.: PCT/CA2O14/051088 pathogens and/or the prevention of diseases associated with the presence of said pathogens in and/or on seeds. Said S 371 (c)(1), composition of water-soluble ingredients (CWSI) comprises (2) Date: May 20, 2016 at least one oxidizer in liquid form or solid form, or a precursor thereof in liquid or solid form, said at least one Related U.S. Application Data agriculturally acceptable solvent is soluble in water (W); the (60) Provisional application No. -

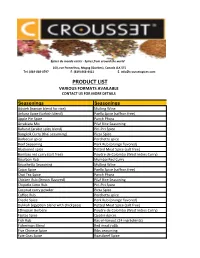

Product List Various Formats Available Contact Us for More Details

Épices du monde entier - Spices from around the world 160, rue Pomerleau, Magog (Quebec), Canada J1X 5T5 Tel. (819-868-0797 F. (819) 868-4411 E. [email protected] PRODUCT LIST VARIOUS FORMATS AVAILABLE CONTACT US FOR MORE DETAILS Seasonings Seasonings Advieh (iranian blend for rice) Mulling Wine Ankara Spice (turkish blend) Paella Spice (saffron free) Apple Pie Spice Panch Phora Arrabiata Mix Pilaf Rice Seasoning Baharat (arabic spicy blend) Piri-Piri Spice Bangkok Curry (thai seasoning) Pizza Spice Barbecue spice Porchetta spice Beef Seasoning Pork Rub (orange flavored) Blackened spice Potted Meat Spice (salt free) Bombay red curry (salt free) Poudre de Colombo (West Indies Curry) Bourbon Rub Mumbai Red Curry Bruschetta Seasoning Mulling Wine Cajun Spice Paella Spice (saffron free) Chai Tea Spice Panch Phora Chicken Rub (lemon flavored) Pilaf Rice Seasoning Chipotle-Lime Rub Piri-Piri Spice Coconut curry powder Pizza Spice Coffee Rub Porchetta spice Creole Spice Pork Rub (orange flavored) Dukkah (egyptian blend with chickpeas) Potted Meat Spice (salt free) Ethiopian Berbéré Poudre de Colombo (West Indies Curry) Fajitas Spice Quatre épices Fish Rub Ras-el-hanout (24 ingrédients) Fisherman Blend Red meat ru8b Five Chinese Spice Ribs seasoning Foie Gras Spice Roastbeef Spice Game Herb Salad Seasoning Game Spice Salmon Spice Garam masala Sap House Blend Garam masala balti Satay Spice Garam masala classic (whole spices) Scallop spice (pernod flavor) Garlic pepper Seafood seasoning Gingerbread Spice Seven Japanese Spice Greek Spice Seven -

Beautiful Blends

beautiful blends YOUR HOME SANCTUARY: 4d lime + 3 grapefruit + 2 clary sage A HOME FILLED WITH LOVE: 3 frankincense + 2 clary sage + 4 grapefruit BEAUTIFUL EVE BLEND: 3 Lime + 2 Bergamot + 2 Arborvitae ANTHROPOLOGIE: 2 drops each of Siberian Fir + Grapefruit + Citrus Bliss VOLCANO: 3 Grapefruit + Wild Orange, 2 Lime, 1 Geranium + Black Spruce SUNSET BLISS: 3 grapefruit, 3 lemon, 1 ylang ylang, 1 spearmint TAHITI: 3 wild orange + 2 ginger + 2 ylang ylang PARADISE: 3 citrus bliss + 2 sandalwood + 3 grapefruit SUMMER HOME: 2 drops each: sandalwood + lemon + lavender HAPPY HIPPY: 3 arborvitae + 2 sandalwood + 2 wild orange SWEET SUMMER SUNSET: 4 Juniper Berry + 2 Grapefruit + 2 Bergamot + 1 Ylang Ylang SUMMER: 1 Patchouli + 2 Bergamot + 3 Wild Orange SUNRISE SESSION: 3 Peppermint + 3 Lemon + 2 Frankincense AUTUMNS SUNRISE: 3 Wild Orange + 2 Cardamom + 2 Cinnamon SLEEPING IN THE MOUNTAINS: 2 drops each Siberian Fir + Lavender GLOW BABE: 4 Citrus Bliss + 2 Whisper (the blend of the HOL:FIT x Rocking Vibe Glow Piece) LEGACY: 4 tangerine, 3 frankincense, 2 wild orange, 2 clary sage, 2 marjoram, 1 ylang clang, 1 Siberian fir (the blend of the HOL:FIT x Rocking Vibe Legacy Piece) BEACH BABE: 3 Whisper + 2 Geranium + 2 Ylang Ylang LOVE: 2 Ylang Ylang + 2 Geranium + 3 Lemon LOVEBIRDS: 2 drops each: Coriander + Wild Orange + Ylang Ylang + Sandalwood SWEETHEARTS: 2 Citrus Bliss + 2 Serenity Blend + 1 Wild Orange BLISS: 2 Serenity + 2 Lime MERMAID COVE: 3 Citrus Bliss + 2 Sandalwood + 3 Grapefruit HARMONY: 3 Patchouli, 2 White Fir, 2 Cinnamon RENEWAL: -

Chicken Breasts in Juniper Berry Gin Cream Sauce

Chicken Breasts in Juniper Berry Gin Cream Sauce 4 boneless, skinless chicken breasts Serves 4 ½ tsp salt ¼ tsp pepper 1 /8 tsp garlic powder 1 TBL butter ½ small red onion, chopped fine ¼ cup gin 1 ½ cups chicken broth ¼ cup loosely packed sage leaves, roughly chopped 1 cup heavy cream 2 TBL dried juniper berries, some lightly crushed 1 tsp fresh lemon juice ½ tsp Dijon mustard 2 TBL Parmesan cheese, finely grated Brought to you by San Antonio Herb Market Association www.sanantonioherbmarket.org Chicken in Juniper Berry Cream Sauce Gently pound the chicken breasts to a uniform thickness. Heat a large skillet over medium-high heat and spray with cooking spray. Season chicken breasts with the salt, pepper, and garlic powder then add to the hot skillet. Cook for 7-8 minutes per side until cooked. Remove to a plate and tent with foil to keep warm. To Make The Cream Sauce: Reduce the heat to medium low and melt the butter in the skillet. Add onion and sauté, stirring occasionally until tender. Increase the heat to medium high and stir in the gin deglazing the skillet and scraping bits on the bottom of the pan. Add the chicken broth and sage. Simmer 10 minutes, lowering the heat as necessary to keep the sauce at a low boil. After 10 minutes stir in the cream and juniper berries. Lower the heat to simmer. Cook, stirring occasionally until the sauce is reduced and thick like heavy cream. Remove the skillet and whisk in the Parmesan cheese, mustard and lemon juice until the cheese has melted. -

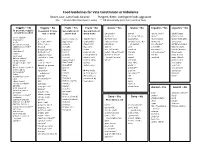

Diet Guidelines for Vata Chart

Food Guidelines for Vata Constitution or Imbalance Sweet, sour, salty foods balance --- Pungent, Bitter, Astringent foods aggravate Key: * OK in moderation (twice a week) ** OK occasionally (once every week or two) Veggies – Yes Veggies – No Fruits – Yes Fruits – No Grains – Yes Grains – No Legumes –Yes Legumes – No In general, veggies In general frozen, Generally most Generally most should be cooked raw or dried sweet fruit dried fruits amaranth* barley lentils (red)* aduki beans couscous bread (yeasted) miso** black beans acorn squash artichoke apples (cooked) apples (raw) durham flour buckwheat mung beans black-eyed peas asparagus beets beet greens** applesauce cranberries oats (cooked) cereals (cold, dry mung dal chick peas butternut squash bitter melon apricots dates (dry) pancakes or puffed) soy cheese* garbanzo beans cabbage (cooked)* broccoli avocado figs (dry) quinoa corn soy milk* kidney beans carrots brussel sprouts bananas pears rice (all kinds) crackers soy sauce* lentils (brown) cauliflower* burdock root berries persimmons seitan (wheat meat) granola soy sausages* lima beans cilantro cabbage (raw) cherries pomegranates sprouted wheat millet tur dal navy beans cucumber raisins (dry) bread (essene) museli peas (dried) daikon radish* cauliflower (raw) coconut urad dal fennel (anise) celery dates (fresh) prunes (dry) wheat oat bran pinto beans fenugreek greens* corn (fresh)** figs (fresh) quince oats (dry) soy beans garlic dandelion greens grapefruit watermelon pasta** soy flour green beans (cooked) eggplant grapes polenta** soy powder green chilies jerusalem kiwi Note: fruits popcorn split peas horseradish* artichoke* lemons & fruit juices rice cakes** tempeh leeks limes mustard greens* jicama* Are best con- rye tofu* okra horseradish** mangoes consumed by sago olives, black kale melons (sweet) themelves. -

0315 Ingredients Column

[INGREDIENTS] by Karen Nachay Spicing Up Food Formulating cuisines continue to have a big impact on culinary applications and consumer packaged food and bever- age products. Using authentic ingredients and drawing inspiration from regional cuisines within larger geographical regions is reflected in menu options and consumer product goods. In addition to global cuisine influencing consumers’ preferences and product development, bold, unusual, or unexpected flavors and ingredients have an effect as well. Many consumers want something different from their food, and ingredi- ents like spices and herbs can give these consumers the taste sensa- tions like heat, sweet, umami, herbaceous, warm, smoke, and more, and allow them to experience the foods and flavors of cuisines from around the world right in their own dining rooms or at local restaurants. “Eating is always an experience for people,” says AnnMarie Kraszewski, Spices and herbs are o plane ticket? No problem. For developers, and home cooks con- food scientist at Wixon Inc., St. global ingredients used a trip around the world, look no tinue to use spices and herbs for Francis, Wis. (www.wixon.com), who for centuries in food further than your spice rack. these purposes, but they also incor- explains that the more complex the preparation. N © Krzysztof Slusarczyk/ There you will find cinnamon from porate these ingredients in flavor profiles are in a food product, iStock/Thinkstock Sri Lanka, Aleppo pepper from Syria, formulations and recipes to differen- the more the consumer will enjoy the saffron from Spain, and so much tiate products, add global or regional product. Product developers and more. -

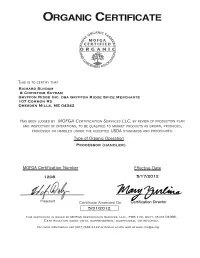

Gryffon Ridge Orgcert3.Pdf

MOFGA CERTIFICATION SERVICES, LLC. ORGANIC PRODUCT VERIFICATION Richard Suydam MOFGA Certification Number: & Christine Suydam Gryffon Ridge Inc. dba Gryffon Ridge Spice 1208 Merchants List Amended On 6/4/2012 11:07:53 AM 107 Common Rd Dresden Mills, ME 04342 The following are certified organic products grown, produced or handled by this certified operation. We have certified them as organic to the USDA National Organic Program (NOP) Standards: Processed Products - Organic Herbs & Spices: Acacia Powder Angelica Root Acai Powder Angelica Root Powder Acerola Powder Angelica Root Powder Afghan Spice Blend Anise Seed Agrimony Anise Seed Agrimony Anise Seed Ajwain Seed Anise Seed Powder Alfalfa Leaf Anise Seed Powder Alfalfa Leaf Anise Star Pod Powder Alfalfa Leaf Powder Anise Star Pods Alfalfa Seed Anise, Star Whole Alflafa Powder Annatto Powder Allspice Ground Annatto Seed, Powder Allspice Powder Annatto Seed, Whole Allspice Powder Annatto Seed, Whole Allspice Whole Apple Pie Spice Allspice Whole Arjuna Powder Allspice Whole Arnica Flowers Whole Amla Powder Arrowroot Powder Amla, Whole Artichoke Leaf Ancho Chile Powder Artichoke Leaf Angelica Root Artichoke Powder Effective Through 5/16/2013 Page - 1 THIS PRODUCT VERIFICATION IS ISSUED BY MOFGA CERTIFICATION SERVICES, LLC. POB 170, UNITY, MAINE 04988 For more information call (207) 568-4142 or find us on the web at www.mofga.org. MOFGA CERTIFICATION SERVICES, LLC. ORGANIC PRODUCT VERIFICATION Richard Suydam MOFGA Certification Number: & Christine Suydam Gryffon Ridge Inc. dba Gryffon Ridge Spice 1208 Merchants List Amended On 6/4/2012 11:07:53 AM 107 Common Rd Dresden Mills, ME 04342 The following are certified organic products grown, produced or handled by this certified operation.