Discussion Guide for METROPOLIS Fritz Lang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ein Deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme Und Der Deutschen Not

Jörg Hackfurth (Gießen) Ein deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme und der Deutschen Not 1. Einleitung In From Caligari to Hitler formuliert der Soziologe Siegfried Kracauer die These, daß „mittels einer Analyse der deutschen Filme tiefenpsychologi- sche Dispositionen, wie sie in Deutschland von 1918 bis 1933 herrschten, aufzudecken sind: Dispositionen, die den Lauf der Ereignisse zu jener Zeit beeinflussen und mit denen in der Zeit nach Hitler zu rechnen sein wird".1 Kracauers analytische Methode beruht auf einigen Prämissen, die hier noch einmal in ihrem originalen Wortlaut wiedergegeben werden sollen: „Die Filme einer Nation reflektieren ihre Mentalität unvermittelter als an- dere künstlerische Medien, und das aus zwei Gründen: Erstens sind Filme niemals das Produkt eines Individuums. [...] Da jeder Filmproduktionsstab eine Mischung heterogener Interessen und Neigungen verkörpert, tendiert die Teamarbeit auf diesem Gebiet dazu, willkürliche Handhabung des Filmmaterials auszuschließen und individuelle Eigenheiten zugunsten jener zu unterdrücken, die vielen Leuten gemeinsam sind. Zweitens richten sich Filme an die anonyme Menge und sprechen sie an. Von populären Filmen [...] ist daher anzunehmen, daß sie herrschende Massenbedürfnisse befrie- digen“2 Daraus resultiert ein Mechanismus, der sowohl in Hollywood als auch in Deutschland Geltung hat: „Hollywood kann es sich nicht leisten, Sponta- neität auf Seiten des Publikums zu ignorieren. Allgemeine Unzufriedenheit zeigt sich in rückläufigen Kasseneinnahmen, und die Filmindustrie, für die Profitinteresse eine Existenzfrage ist, muß sich so weit wie möglich den Veränderungen des geistigen Klimas anpassen".3 Ferner gilt: „Was die Filme reflektieren, sind weniger explizite Überzeu- gungen als psychologische Dispositionen – jene Tiefenschichten der Kol- lektivmentalität, die sich mehr oder weniger unterhalb der Bewußtseins- dimension erstrecken. -

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

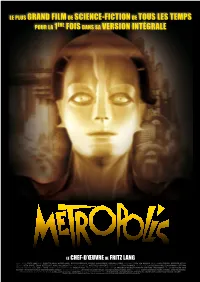

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

From Iron Age Myth to Idealized National Landscape: Human-Nature Relationships and Environmental Racism in Fritz Lang’S Die Nibelungen

FROM IRON AGE MYTH TO IDEALIZED NATIONAL LANDSCAPE: HUMAN-NATURE RELATIONSHIPS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM IN FRITZ LANG’S DIE NIBELUNGEN Susan Power Bratton Whitworth College Abstract From the Iron Age to the modern period, authors have repeatedly restructured the ecomythology of the Siegfried saga. Fritz Lang’s Weimar lm production (released in 1924-1925) of Die Nibelungen presents an ascendant humanist Siegfried, who dom- inates over nature in his dragon slaying. Lang removes the strong family relation- ships typical of earlier versions, and portrays Siegfried as a son of the German landscape rather than of an aristocratic, human lineage. Unlike The Saga of the Volsungs, which casts the dwarf Andvari as a shape-shifting sh, and thereby indis- tinguishable from productive, living nature, both Richard Wagner and Lang create dwarves who live in subterranean or inorganic habitats, and use environmental ideals to convey anti-Semitic images, including negative contrasts between Jewish stereo- types and healthy or organic nature. Lang’s Siegfried is a technocrat, who, rather than receiving a magic sword from mystic sources, begins the lm by fashioning his own. Admired by Adolf Hitler, Die Nibelungen idealizes the material and the organic in a way that allows the modern “hero” to romanticize himself and, with- out the aid of deities, to become superhuman. Introduction As one of the great gures of Weimar German cinema, Fritz Lang directed an astonishing variety of lms, ranging from the thriller, M, to the urban critique, Metropolis. 1 Of all Lang’s silent lms, his two part interpretation of Das Nibelungenlied: Siegfried’s Tod, lmed in 1922, and Kriemhilds Rache, lmed in 1923,2 had the greatest impression on National Socialist leaders, including Adolf Hitler. -

Heng-Moduleawk7-Metropolis.Pdf

Phone: (02) 8007 6824 DUX Email: [email protected] Web: dc.edu.au 2018 HIGHER SCHOOL CERTIFICATE COURSE MATERIALS HSC English Advanced Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 Name ………………………………………………………. Class day and time ………………………………………… Teacher name ……………………………………………... HSC English Advanced - Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 1 DUX Term 1 – Week 7 – Theory • Film Analysis • Homework FILM ANALYSIS SEGMENT SIX (THE MACHINE-MAN) After discovering the workers' clandestine meeting, Freder's controlling, glacial father conspires with mad scientist Rotwang to create an evil, robotic Maria duplicate, in order to manipulate his workers and preach riot and rebellion. Fredersen could then use force against his rebellious workers that would be interpreted as justified, causing their self-destruction and elimination. Ultimately, robots would be capable of replacing the human worker, but for the time being, the robot would first put a stop to their revolutionary activities led by the good Maria: "Rotwang, give the Machine-Man the likeness of that girl. I shall sow discord between them and her! I shall destroy their belief in this woman --!" After Joh Fredersen leaves to return above ground, Rotwang predicts doom for Joh's son, knowing that he will be the workers' mediator against his own father: "You fool! Now you will lose the one remaining thing you have from Hel - your son!" Rotwang comes out of hiding, and confronts Maria, who is now alone deep in the catacombs (with open graves and skeletal remains surrounding her). He pursues her - in the expressionistic scene, he chases her with the beam of light from his bright flashlight, then corners her, and captures her when she cannot escape at a dead-end. -

Cinema 2: the Time-Image

m The Time-Image Gilles Deleuze Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Caleta M IN University of Minnesota Press HE so Minneapolis fA t \1.1 \ \ I U III , L 1\) 1/ ES I /%~ ~ ' . 1 9 -08- 2000 ) kOTUPHA\'-\t. r'Y'f . ~ Copyrigh t © ~1989 The A't1tl ----resP-- First published as Cinema 2, L1111age-temps Copyright © 1985 by Les Editions de Minuit, Paris. ,5eJ\ Published by the University of Minnesota Press III Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 f'tJ Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 1'::>55 Fifth printing 1997 :])'''::''531 ~ Library of Congress Number 85-28898 ISBN 0-8166-1676-0 (v. 2) \ ~~.6 ISBN 0-8166-1677-9 (pbk.; v. 2) IJ" 2. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or othenvise, ,vithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Preface to the English Edition Xl Translators'Introduction XV Chapter 1 Beyond the movement-image 1 How is neo-realism defined? - Optical and sound situations, in contrast to sensory-motor situations: Rossellini, De Sica - Opsigns and sonsigns; objectivism subjectivism, real-imaginary - The new wave: Godard and Rivette - Tactisigns (Bresson) 2 Ozu, the inventor of pure optical and sound images Everyday banality - Empty spaces and stilllifes - Time as unchanging form 13 3 The intolerable and clairvoyance - From cliches to the image - Beyond movement: not merely opsigns and sonsigns, but chronosigns, lectosigns, noosigns - The example of Antonioni 18 Chapter 2 ~ecaPitulation of images and szgns 1 Cinema, semiology and language - Objects and images 25 2 Pure semiotics: Peirce and the system of images and signs - The movement-image, signaletic material and non-linguistic features of expression (the internal monologue). -

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism By

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anton Kaes, Chair Professor Martin Jay Professor Linda Williams Fall 2015 Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism © 2015 by Nicholas Walter Baer Abstract Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Anton Kaes, Chair This dissertation intervenes in the extensive literature within Cinema and Media Studies on the relationship between film and history. Challenging apparatus theory of the 1970s, which had presumed a basic uniformity and historical continuity in cinematic style and spectatorship, the ‘historical turn’ of recent decades has prompted greater attention to transformations in technology and modes of sensory perception and experience. In my view, while film scholarship has subsequently emphasized the historicity of moving images, from their conditions of production to their contexts of reception, it has all too often left the very concept of history underexamined and insufficiently historicized. In my project, I propose a more reflexive model of historiography—one that acknowledges shifts in conceptions of time and history—as well as an approach to studying film in conjunction with historical-philosophical concerns. My project stages this intervention through a close examination of the ‘crisis of historicism,’ which was widely diagnosed by German-speaking intellectuals in the interwar period. -

Creacion Y Produccion Nº 1

Creación y Producción en Diseño y Comunicación Universidad de Palermo [Trabajos de estudiantes y egresados] Universidad de Palermo. Rector Facultad de Diseño y Comunicación. Ricardo Popovsky Centro de Estudios en Diseño y Comunicación. Mario Bravo 1050. Facultad de Diseño y Comunicación C1175ABT. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Decano Argentina. [email protected] Oscar Echevarría Director Escuela de Diseño Oscar Echevarría Secretario Académico Jorge Gaitto Editor Estela Pagani Escuela de Comunicación Secretario Académico Coordinador del Nº 1 Jorge Surraco Alejandro Cristian Fernández Comité Editorial Centro de Estudios en Diseño y Comunicación María Elsa Bettendorff. Universidad de Palermo, Argentina. Coordinador Allan Castelnuovo. Market Research Society. Londres. Estela Pagani Reino Unido. Raúl Castro. Universidad de Palermo. Argentina. Centro de Producción en Diseño y Comunicación Michael Dinwiddie. New York University. EE.UU. Coordinador Marcelo Ghio. Universidad de Palermo. Argentina. Marcelo Ghío Andrea Noble. University of Durham. Reino Unido. Joanna Page. Cambridge University, CELA. Reino Unido. Hugo Pardo. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. España. Ernesto Pesci Gaytán. Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas. México. Daissy Piccinni. Universidad de San Pablo. Brasil. Fernando Rolando. Universidad de Palermo. Argentina. Comité de Arbitraje Pablo Barilari. Profesor del Departamento de Diseño Gráfico. Alberto Farina. Profesor del Departamento de Cine y Televisión. Patricia Iurcovich. Profesor del Departamento de Relaciones Públicas. Fabiola Knop. Profesor del Departamento de Publicidad. Carlos Morán. Profesor del Departamento de Diseño Gráfico. Estela Reca. Profesor del Departamento de Diseño de Interiores. Pedro Reissig. Profesor del Departamento de Diseño Industrial. Viviana Suárez. Profesor del Departamento de Diseño Gráfico. Textos en Inglés Diana Divasto Textos en Portugués Daniela Scalco Piñeiro Diseño Constanza Togni Web Natalia Filippini Juan Miguel Franco 1º Edición. -

Towards a History of the Serial Killer in German Film History

FOCUS ON GERMAN STUDIES 14 51 “Warte, warte noch ein Weilchen...” – Towards a History of the Serial Killer in German Film History JÜRGEN SCHACHERL Warte, warte noch ein Weilchen, dann kommt Haarmann auch zu dir, mit dem Hackehackebeilchen macht er Leberwurst aus dir. - German nursery rhyme t is not an unknown tendency for dark events to be contained and to find expression in nursery rhymes and children’s verses, such as I the well-known German children’s rhyme above. At first instance seemingly no more than a mean, whiny playground chant, it in fact alludes to a notorious serial killer who preyed on young male prostitutes and homeless boys. Placed in this context, the possible vulgar connotations arising from Leberwurst become all the more difficult to avoid recognizing. The gravity of these events often becomes drowned out by the sing-song iambics of these verses; their teasing melodic catchiness facilitates the overlooking of their lyrical textual content, effectively down-playing the severity of the actual events. Moreover, the containment in common fairy tale-like verses serves to mythologize the subject matter, rendering it gradually more fictitious until it becomes an ahistorical prototype upon a pedestal. Serial killer and horror films have to an arguably large extent undergone this fate – all too often simply compartmentalized in the gnarly pedestal category of “gore and guts” – in the course of the respective genres’ development and propagation, particularly in the American popular film industry: Hollywood. The gravity and severity of the serial murder phenomenon become drowned in an indifferent bloody splattering of gory effects. -

Fritz Lang Und Genitiv-Schlüssel

Fritz Lang und Genitiv—Drehbuchautor, Regisseur, adaptiert von http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/biografien/LangFritz/ Deutsch 4 Name______________________ Bitte die Lücken ergänzen, um das richtige Form des Genitivs zu machen. 1890 5. Dezember: Fritz Lang wird als Sohn des____ Architekten_____Anton Lang und dessen Frau Paula (geb. Schlesinger) in Wien geboren. 1907 Nach dem Besuch der___Realschule_/___ beginnt Lang auf Wunsch des_____Vaters____ ein Bauingenieurstudium an der Technischen Hochschule in Wien. 1908 Er wechselt zum Studium der______ Malerei__/__ an die Wiener Akademie der______ Graphischen_____ Künste ___/___. Neben dem Studium tritt er als Kabarettist auf. ab 1910 Er unternimmt größere Reisen, die ihn unter anderem in Mittelmeerländer und nach Afrika führen. 1911 Lang geht nach München, um an der Kunstgewerbeschule zu studieren. Dort bleibt er jedoch nur für kurze Zeit, da er wieder auf Reisen geht. 1913/14 Er setzt seine Ausbildung in Paris bei dem Maler Maurice Denis (1870-1943) fort. Durch das französische Kino findet er intensiven Zugang zum neuen Medium Film. 1914 Mit Beginn des_ Erst_en____ Welkrieg_es____ kehrt Lang nach Wien zurück, um sich als Kriegsfreiwilliger zu melden. 1916 Nach einer Kriegsverletzung kommt er zum Genesungsurlaub wieder nach Wien. Lang knüpft erste Kontakte zu Filmleuten und beginnt als Drehbuchautor zu arbeiten. 1917 Lang muß nach seiner Genesung an die Front zurück. 1918 Er wird nach einer zweiten Verwundung für kriegsuntauglich erklärt. Bei einem Schauspiel im Rahmen der_____ Truppenbetreuung___/____ arbeitet er zum ersten Mal als Regisseur. Lang siedelt nach Berlin über, um als Dramaturg tätig zu werden. 1919 Mit dem in fünf Tagen gedrehten Stummfilm "Halbblut" hat Lang sein Regiedebüt.