Metropolis Fritz Lang, D 1925 / 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

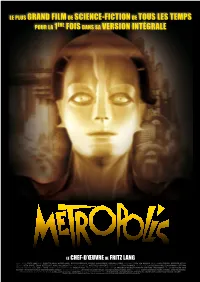

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1

* pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. These films shed light on the way Ger- many chose to remember its recent past. A body of twenty-five films is analysed. For insight into the understanding and reception of these films at the time, hundreds of film reviews, censorship re- ports and some popular history books are discussed. This is the first rigorous study of these hitherto unacknowledged war films. The chapters are ordered themati- cally: war documentaries, films on the causes of the war, the front life, the war at sea and the home front. Bernadette Kester is a researcher at the Institute of Military History (RNLA) in the Netherlands and teaches at the International School for Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Am- sterdam. She received her PhD in History FilmFilm FrontFront of Society at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. She has regular publications on subjects concerning historical representation. WeimarWeimar Representations of the First World War ISBN 90-5356-597-3 -

From Iron Age Myth to Idealized National Landscape: Human-Nature Relationships and Environmental Racism in Fritz Lang’S Die Nibelungen

FROM IRON AGE MYTH TO IDEALIZED NATIONAL LANDSCAPE: HUMAN-NATURE RELATIONSHIPS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM IN FRITZ LANG’S DIE NIBELUNGEN Susan Power Bratton Whitworth College Abstract From the Iron Age to the modern period, authors have repeatedly restructured the ecomythology of the Siegfried saga. Fritz Lang’s Weimar lm production (released in 1924-1925) of Die Nibelungen presents an ascendant humanist Siegfried, who dom- inates over nature in his dragon slaying. Lang removes the strong family relation- ships typical of earlier versions, and portrays Siegfried as a son of the German landscape rather than of an aristocratic, human lineage. Unlike The Saga of the Volsungs, which casts the dwarf Andvari as a shape-shifting sh, and thereby indis- tinguishable from productive, living nature, both Richard Wagner and Lang create dwarves who live in subterranean or inorganic habitats, and use environmental ideals to convey anti-Semitic images, including negative contrasts between Jewish stereo- types and healthy or organic nature. Lang’s Siegfried is a technocrat, who, rather than receiving a magic sword from mystic sources, begins the lm by fashioning his own. Admired by Adolf Hitler, Die Nibelungen idealizes the material and the organic in a way that allows the modern “hero” to romanticize himself and, with- out the aid of deities, to become superhuman. Introduction As one of the great gures of Weimar German cinema, Fritz Lang directed an astonishing variety of lms, ranging from the thriller, M, to the urban critique, Metropolis. 1 Of all Lang’s silent lms, his two part interpretation of Das Nibelungenlied: Siegfried’s Tod, lmed in 1922, and Kriemhilds Rache, lmed in 1923,2 had the greatest impression on National Socialist leaders, including Adolf Hitler. -

Heng-Moduleawk7-Metropolis.Pdf

Phone: (02) 8007 6824 DUX Email: [email protected] Web: dc.edu.au 2018 HIGHER SCHOOL CERTIFICATE COURSE MATERIALS HSC English Advanced Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 Name ………………………………………………………. Class day and time ………………………………………… Teacher name ……………………………………………... HSC English Advanced - Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 1 DUX Term 1 – Week 7 – Theory • Film Analysis • Homework FILM ANALYSIS SEGMENT SIX (THE MACHINE-MAN) After discovering the workers' clandestine meeting, Freder's controlling, glacial father conspires with mad scientist Rotwang to create an evil, robotic Maria duplicate, in order to manipulate his workers and preach riot and rebellion. Fredersen could then use force against his rebellious workers that would be interpreted as justified, causing their self-destruction and elimination. Ultimately, robots would be capable of replacing the human worker, but for the time being, the robot would first put a stop to their revolutionary activities led by the good Maria: "Rotwang, give the Machine-Man the likeness of that girl. I shall sow discord between them and her! I shall destroy their belief in this woman --!" After Joh Fredersen leaves to return above ground, Rotwang predicts doom for Joh's son, knowing that he will be the workers' mediator against his own father: "You fool! Now you will lose the one remaining thing you have from Hel - your son!" Rotwang comes out of hiding, and confronts Maria, who is now alone deep in the catacombs (with open graves and skeletal remains surrounding her). He pursues her - in the expressionistic scene, he chases her with the beam of light from his bright flashlight, then corners her, and captures her when she cannot escape at a dead-end. -

Cinema 2: the Time-Image

m The Time-Image Gilles Deleuze Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Caleta M IN University of Minnesota Press HE so Minneapolis fA t \1.1 \ \ I U III , L 1\) 1/ ES I /%~ ~ ' . 1 9 -08- 2000 ) kOTUPHA\'-\t. r'Y'f . ~ Copyrigh t © ~1989 The A't1tl ----resP-- First published as Cinema 2, L1111age-temps Copyright © 1985 by Les Editions de Minuit, Paris. ,5eJ\ Published by the University of Minnesota Press III Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 f'tJ Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 1'::>55 Fifth printing 1997 :])'''::''531 ~ Library of Congress Number 85-28898 ISBN 0-8166-1676-0 (v. 2) \ ~~.6 ISBN 0-8166-1677-9 (pbk.; v. 2) IJ" 2. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or othenvise, ,vithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Preface to the English Edition Xl Translators'Introduction XV Chapter 1 Beyond the movement-image 1 How is neo-realism defined? - Optical and sound situations, in contrast to sensory-motor situations: Rossellini, De Sica - Opsigns and sonsigns; objectivism subjectivism, real-imaginary - The new wave: Godard and Rivette - Tactisigns (Bresson) 2 Ozu, the inventor of pure optical and sound images Everyday banality - Empty spaces and stilllifes - Time as unchanging form 13 3 The intolerable and clairvoyance - From cliches to the image - Beyond movement: not merely opsigns and sonsigns, but chronosigns, lectosigns, noosigns - The example of Antonioni 18 Chapter 2 ~ecaPitulation of images and szgns 1 Cinema, semiology and language - Objects and images 25 2 Pure semiotics: Peirce and the system of images and signs - The movement-image, signaletic material and non-linguistic features of expression (the internal monologue). -

Verlängert Bis 25. Mai 2008

Verlängert bis 25. Mai 2008 WENN ICH SONNTAGS IN MEIN KINO GEH’. TON-FILM-MUSIK 1929-1933 Sonderausstellung der Deutschen Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen Lilian Harvey, um 1930, Quelle: Deutsche Kinemathek Ausstellung 20. Dezember 07 bis 27. April 08 Ort Museum für Film und Fernsehen im Filmhaus, 1. OG Potsdamer Straße 2, 10785 Berlin www.deutsche-kinemathek.de Filmreihe ab 20. Dezember 07 Kino Arsenal im Filmhaus, 2. UG www.fdk-berlin.de Publikationen Begleitbuch „Wenn ich sonntags in mein Kino geh’. Ton-Film-Musik 1929-1933“ inklusive CD „Wenn ich sonntags in mein Kino geh’. Ton-Film-Musik 1929-1933“ Gefördert durch www.deutsche-kinemathek.de/Pressestelle T. 030/300903-820 WENN ICH SONNTAGS IN MEIN KINO GEH’. TON-FILM-MUSIK 1929-1933 20. Dezember 07 bis 27. April 08 DATEN Ausstellungsort Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen Filmhaus, 1. OG, Potsdamer Straße 2, 10785 Berlin Informationen Tel. 030/300903-0, Fax 030/300903-13 www.deutsche-kinemathek.de Publikation Begleitbuch inkl. Audio-CD „Wenn ich sonntags in mein Kino geh’. Ton-Film-Musik 1929-1933“, Museumsausgabe: 18,90 € Öffnungszeiten Dienstag bis Sonntag 10 bis 18 Uhr, Donnerstag 10 bis 20 Uhr Feiertage 24.12. geschlossen, 25., 26., 31.12. geöffnet, 1.1.08 ab 12 Uhr Eintritt 4 Euro / 3 Euro ermäßigt 6 Euro / 4,50 Euro ermäßigt inkl. Ständige Ausstellungen 3 Euro Schüler 12 Euro Familienticket (2 Erwachsene mit Kindern) 6 Euro Kleines Familienticket (1 Erwachsener mit Kindern) Führungen Anmeldung »FührungsNetz«: T 030/24749-888 Ausstellungsfläche 450 Quadratmeter Exponate ca. 230 Idee und Leitung Rainer Rother Projektsteuerung Peter Mänz Kuratorenteam Peter Jammerthal, Peter Mänz, Vera Thomas, Nils Warnecke Kuratorische Mitarbeit Ursula Breymayer, Judith Prokasky AV Medienprogramm Nils Warnecke Ausstellungsorganisation Vera Thomas Wiss. -

Transatlantica, 2 | 2006 Film and Art : on the German Expressionist and the Disney Exhibitions 2

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 2 | 2006 Révolution Film and Art : On the German Expressionist and the Disney Exhibitions Penny Starfield Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/1192 DOI : 10.4000/transatlantica.1192 ISSN : 1765-2766 Éditeur AFEA Référence électronique Penny Starfield, « Film and Art : On the German Expressionist and the Disney Exhibitions », Transatlantica [En ligne], 2 | 2006, mis en ligne le 23 janvier 2007, consulté le 29 avril 2021. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/1192 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.1192 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 29 avril 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Film and Art : On the German Expressionist and the Disney Exhibitions 1 Film and Art : On the German Expressionist and the Disney Exhibitions Penny Starfield Le Cinéma expressionniste allemand, La Cinémathèque française, curators : Marianne de Fleury and Laurent Mannoni, October 26, 2006-January 22, 2007. Il était une fois Walt Disney, aux sources de l’art des studios Disney, curator : Bruno Girveau, Le Grand Palais, September 16, 2006-January 15, 2007 ; Musée des Beaux- Arts, Montréal, 8 March-24 June 2007. 1 Two major exhibitions in Paris delve into the relationship between the artistic and the film worlds. The German Expressionists in Film celebrates the seventieth anniversary of the French Cinémathèque, founded by Henri Langlois in 1936. It is housed in the temporary exhibition space on the fifth floor of the recently-inaugurated Cinémathèque, which moved from its historic site at the Palais de Chaillot to the luminous building conceived by Frank Gehry on the far eastern side of the right bank. -

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism By

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anton Kaes, Chair Professor Martin Jay Professor Linda Williams Fall 2015 Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism © 2015 by Nicholas Walter Baer Abstract Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Anton Kaes, Chair This dissertation intervenes in the extensive literature within Cinema and Media Studies on the relationship between film and history. Challenging apparatus theory of the 1970s, which had presumed a basic uniformity and historical continuity in cinematic style and spectatorship, the ‘historical turn’ of recent decades has prompted greater attention to transformations in technology and modes of sensory perception and experience. In my view, while film scholarship has subsequently emphasized the historicity of moving images, from their conditions of production to their contexts of reception, it has all too often left the very concept of history underexamined and insufficiently historicized. In my project, I propose a more reflexive model of historiography—one that acknowledges shifts in conceptions of time and history—as well as an approach to studying film in conjunction with historical-philosophical concerns. My project stages this intervention through a close examination of the ‘crisis of historicism,’ which was widely diagnosed by German-speaking intellectuals in the interwar period. -

Metropolis DVD Study Edition

Metropolis DVD Study Edition Film institute | DVD as a medium for critical film editions 2 Table of Contents Preface | Heinz Emigholz 3 Preface | Hortensia Völckers 4 Preface | Friedemann Beyer 5 DVD: Old films, new readings | Enno Patalas 6 Edition of a torso | Anna Bohn 8 Le tableau disparu | Björn Speidel 12 Navigare necesse est | Gunter Krüger 15 Navigation-Model 18 New Tower Metropolis | Enno Patalas 20 Making the invisible “visible” | Franziska Latell & Antje Michna 23 Metropolis, 1927 | Gottfried Huppertz 26 Metropolis, 2005 | Mark Pogolski & Aljioscha Zimmermann 27 Metropolis – Synopsis 28 Film Specifications 29 Contributors 30 Imprint 33 Thanks 35 3 Preface Many versions and editions exist of the film Metropolis, dating back to its very first screening in 1927. Commercial distribution practice at the time of the premiere cut films after their initial screening and recompiled them according to real or imaginary demands. Even the technical requirements for production of different language versions of the film raise the question just which “original” is to be protected or reconstructed. In other fields of the arts the stature and authority that even a scratched original exudes is not given in the “history of film”. There may be many of the kind, and gene- rations of copies make only for a cluster of “originals”. Reconstruction work is therefore essentially also the perception of a com- plex and viable happening only to be understood in terms of a timeline – linear and simultaneous at one and the same time. The consumer’s wish for a re-constructible film history following regular channels and self-con- tained units cannot, by its very nature, be satisfied; it is, quite simply, not logically possible.