Creating Perspective in Narrative Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Cambridge Companion Shakespeare on Film

This page intentionally left blank Film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays are increasingly popular and now figure prominently in the study of his work and its reception. This lively Companion is a collection of critical and historical essays on the films adapted from, and inspired by, Shakespeare’s plays. An international team of leading scholars discuss Shakespearean films from a variety of perspectives:as works of art in their own right; as products of the international movie industry; in terms of cinematic and theatrical genres; and as the work of particular directors from Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles to Franco Zeffirelli and Kenneth Branagh. They also consider specific issues such as the portrayal of Shakespeare’s women and the supernatural. The emphasis is on feature films for cinema, rather than television, with strong cov- erage of Hamlet, Richard III, Macbeth, King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. A guide to further reading and a useful filmography are also provided. Russell Jackson is Reader in Shakespeare Studies and Deputy Director of the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. He has worked as a textual adviser on several feature films including Shakespeare in Love and Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V, Much Ado About Nothing, Hamlet and Love’s Labour’s Lost. He is co-editor of Shakespeare: An Illustrated Stage History (1996) and two volumes in the Players of Shakespeare series. He has also edited Oscar Wilde’s plays. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO SHAKESPEARE ON FILM CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Old English The Cambridge Companion to William Literature Faulkner edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Philip M. -

Narrowing the Gap Between Imaginary and Real Artifacts: a Process for Making and Filming Diegetic Prototypes

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Narrowing the Gap Between Imaginary and Real Artifacts: A Process for Making and Filming Diegetic Prototypes Al Hussein Wanas Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3142 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Al Hussein Wanas 2013 All Rights Reserved 2 Approval certificate for Al Hussein Wanas for the thesis project entitled Narrowing The Gap Between Imaginary And Real Artifacts: A Process For Making And Filming Diegetic Prototypes. Submitted to the faculty of the Master of Fine Arts in Design Studies of Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar in partial fulfillment for the degree, Master of Fine Arts in Design Studies. Al Hussein Wanas, BFA In Graphic Design, Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar, Doha Qatar, May 2011. Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar, Doha Qatar, May 2013 Diane Derr ______________________ Primary Advisor, Assistant Professor Master of Fine Arts in Design Studies Patty Paine ______________________ Secondary Advisor, Reader, Assistant Professor Liberal Arts and Science Levi Hammett ______________________ Secondary -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2015 "We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form Kendall G. Pack Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pack, Kendall G., ""We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form" (2015). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4247. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4247 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “WE WANT TO GET DOWN TO THE NITTY-GRITTY”: THE MODERN HARDBOILED DETECTIVE IN THE NOVELLA FORM by Kendall G. Pack A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in English (Literature and Writing) Approved: ____________________________ ____________________________ Charles Waugh Brian McCuskey Major Professor Committee Member ____________________________ ____________________________ Benjamin Gunsberg Mark McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2015 ii Copyright © Kendall Pack 2015 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “We want to get down to the nitty-gritty”: The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form by Kendall G. Pack, Master of Science Utah State University, 2015 Major Professor: Dr. Charles Waugh Department: English This thesis approaches the issue of the detective in the 21st century through the parodic novella form. -

The Effects of Diegetic and Nondiegetic Music on Viewers’ Interpretations of a Film Scene

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Psychology: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 6-2017 The Effects of Diegetic and Nondiegetic Music on Viewers’ Interpretations of a Film Scene Elizabeth M. Wakefield Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Siu-Lan Tan Kalamazoo College Matthew P. Spackman Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/psychology_facpubs Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Wakefield, Elizabeth M.; an,T Siu-Lan; and Spackman, Matthew P.. The Effects of Diegetic and Nondiegetic Music on Viewers’ Interpretations of a Film Scene. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 34, 5: 605-623, 2017. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, Psychology: Faculty Publications and Other Works, http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/mp.2017.34.5.605 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © The Regents of the University of California 2017 Effects of Diegetic and Nondiegetic Music 605 THE EFFECTS OF DIEGETIC AND NONDIEGETIC MUSIC ON VIEWERS’ INTERPRETATIONS OF A FILM SCENE SIU-LAN TAN supposed or proposed by the film’s fiction’’ (Souriau, Kalamazoo College as cited by Gorbman, 1987, p. 21). Film music is often described with respect to its relation to this fictional MATTHEW P. S PACKMAN universe. Diegetic music is ‘‘produced within the implied Brigham Young University world of the film’’ (Kassabian, 2001, p. -

The Marriage of Mimesis and Diegesis in "White Teeth"

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 2019 Award Winners - Hulsman Undergraduate Jim & Mary Lois Hulsman Undergraduate Library Library Research Award Research Award Spring 2019 The aM rriage of Mimesis and Diegesis in "White Teeth" Brittany R. Raymond University of New Mexico, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ugresearchaward_2019 Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Raymond, Brittany R.. "The aM rriage of Mimesis and Diegesis in "White Teeth"." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ ugresearchaward_2019/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jim & Mary Lois Hulsman Undergraduate Library Research Award at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2019 Award Winners - Hulsman Undergraduate Library Research Award by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Raymond 1 Brittany Raymond Professor Woodward ENGL 250 28 April 2018 The Marriage of Mimesis and Diegesis in White Teeth Zadie Smith’s literary masterpiece, White Teeth, employs a yin-yang relationship between Mimesis and Diegesis, shifting the style of narration as Smith skillfully maneuvers between the past and present. As the novel is unfolding, two distinctive writing styles complement each other; we are given both brief summaries and long play-by-play descriptions of the plot, depending on the scene. Especially as the story reaches its climax with Irie, Magid and Millat, Smith begins to interchange the styles more frequently, weaving them together in the same scenes. These two literary styles are grounded in Structuralist theory, which focuses on the function of the language itself. -

Brakhage Program 2012

The Brakhage Center Symposium 2012 Quickly becoming a tradition in the world of avant-garde filmmaking and artistry, the Brakhage Center Symposium will again be hosted this year by the University of Colorado at Boulder. In a weekend dedicated to the exploration of new ideas in cinema art, guest programmer Kathy Geritz explores Experimental Narrative. Presenters will include Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Amie Siegel, J.J. Murphy, Chris Sullivan, and Stacey Steers with musical guests The Boulder Laptop Orchestra (BLOrk). Program of Events Friday, March 16 (Muenzinger Auditorium on the CU Campus) 7:00- Multiple and Repeated Narratives 10:00 Screening: Syndromes and A Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2006) Apichatpong Weerasethakul in Person. Saturday, March 17 (Visual Arts Complex 1B20 on the CU Campus) 10:00- Narratives Remade, Reused, and Revisited 12:00 Amie Siegel and Stacey Steers in Person. 1:30- Andy Warhol and Narrative 4:00 Filmmaker and critic J.J. Murphy will lecture on Warhol and narrative. 5:00- Lumière Revisited: Documentary and Narrative Hybrids 7:30 Amie Siegel, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and J. J. Murphy in Person. Sunday, March 18 (Visual Arts Complex 1B20 on the CU Campus) 10:30- Animation and Personal Journeys 1:30 Stacey Steers and Chris Sullivan in Person. 3:00- Méliès Revisited: Dreams and Fantasies 4:30 J.J. Murphy, Chris Sullivan, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul in Person. Special guest performance by BLOrk. (Boulder Laptop Orchestra) Topic: Experimental Narrative "We know what a narrative film is, and what an experimental film is, but what is an experimental narrative? Programmer Profile The selection of films and videos presented in this year’s Kathy Geritz symposium will present various ways filmmakers are Kathy Geritz is a film curator at Pacific Film Archive, exploring this terrain. -

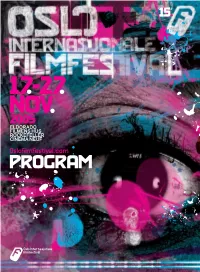

Programmagasin 2005

15. oslO INTERNASJONALE FILMFESTIVal 17.-27. november 2005 VELKOMMEN TIL 15. OSLO INTERNASJONALE FILMFESTIVAL 17.-27 NOVEMBER 2005 Velkommen til ny runde med filmfestdager i Oslo. På nytt kan vi tilby et fantastisk program med aktuelle og spennende filmer. Som tidligere vil vi underholde, forarge, skremme og utfordre. Sjekk det beste vi har funnet via godt samarbeid med norske filmimportører. Opplev også filmer som du kanskje aldri seinere får se i Norge. En haug med internasjonale prisvinnere fra Sundance, Berlin, Cannes, Venezia med flere. Vi åpner med en nordisk premiere av George Clooneys filmregi nr. 2: Good Night, and Good Luck. Om legendariske nyhetsjournalister på 50-tallet som ikke vek unna for fokus på rasisme og maktmisbruk. Og hvordan misbruk av frykt som våpen da som nå er en trussel for ethvert demokrati. Kritikerpris, pluss beste manus og skuespiller i Venezia. Åpningsfilm i New York, avslutning i London. Japansk film er på sitt beste i Canary med et gripende portrett av barns verden. Støymusikk lanseres som effektivt middel mot virustrusler i Eli, Eli,..Ny fantasiferd innen japapansk animé med Mind Game. Nordisk festivalpremiere i spesialvisning: Walk the Line, sterkt og vakkert. Suverent tolker Joaquin Phoenix og Reese Witherspoon våre helter Johnny Cash og June Carter. Mer musikk blir det i dypt personlige og inspirerende portretter av unike musikere og kulthelter som Townes Van Zandt, Roky Erickson (regibesøk) og Billy Childish. Og all slags metal får sitt kart og sin fanbegeistrede hyllest i Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey. Fantasifullt, absurd og/eller sprøtt blir møtet med Mirrormask, Bangkok Loco, The District! og Night Watch. -

The End of the Tour

Two men bare their souls as they struggle with life, creative expression, addiction, culture and depression. The End of the Tour The End of the Tour received accolades from Vanity Fair, Sundance Film Festival, the movie critic Roger Ebert, the New York Times and many more. Tour the film locations and explore the places where actors Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg spent their downtime. Get the scoop and discover entertaining, behind-the-scene stories and more. The End of the Tour follows true events and the relationship between acclaimed author David Foster Wallace and Rolling Stone reporter David Lipsky. Jason Segel plays David Foster Wallace who committed suicide in 2008, while Jesse Eisenberg plays the Rolling Stone reporter who followed Wallace around the country for five days as he promoted his book, Infinite Jest. right before the bookstore opened up again. All the books on the shelves had to come down and were replaced by books that were best sellers and poplar at the time the story line took place. Schuler Books has a fireplace against one wall which was covered up with shelving and books and used as the backdrop for the scene. Schuler Books & Music is one of the nation’s largest independent bookstores. The bookstore boasts a large selection of music, DVDs, gift items, and a gourmet café. PHOTO: EMILY STAVROU-SCHAEFER, SCHULER BOOKS STAVROU-SCHAEFER, PHOTO: EMILY PHOTO: JANET KASIC DAVID FOSTER WALLACE’S HOUSE 5910 72nd Avenue, Hudsonville Head over to the house that served as the “home” of David Foster Wallace. This home (15 miles from Grand Rapids) is where all house scenes were filmed. -

Film Culture in Transition

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art ERIKA BALSOM Amsterdam University Press Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Erika Balsom This book is published in print and online through the online OAPEN library (www.oapen.org) OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative in- itiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. Sections of chapter one have previously appeared as a part of “Screening Rooms: The Movie Theatre in/and the Gallery,” in Public: Art/Culture/Ideas (), -. Sections of chapter two have previously appeared as “A Cinema in the Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins,” Screen : (December ), -. Cover illustration (front): Pierre Bismuth, Following the Right Hand of Louise Brooks in Beauty Contest, . Marker pen on Plexiglas with c-print, x inches. Courtesy of the artist and Team Gallery, New York. Cover illustration (back): Simon Starling, Wilhelm Noack oHG, . Installation view at neugerriemschneider, Berlin, . Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy of the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, and Casey Kaplan, New York. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: JAPES, Amsterdam isbn e-isbn (pdf) e-isbn (ePub) nur / © E. Balsom / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Hollywood Cinema Walter C

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Publications Department of Cinema and Photography 2006 Hollywood Cinema Walter C. Metz Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/cp_articles Recommended Citation Metz, Walter C. "Hollywood Cinema." The Cambridge Companion to Modern American Culture. Ed. Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. (Jan 2006): 374-391. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Cinema and Photography at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Hollywood Cinema” By Walter Metz Published in: The Cambridge Companion to Modern American Culture. Ed. Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006. 374-391. Hollywood, soon to become the United States’ national film industry, was founded in the early teens by a group of film companies which came to Los Angeles at first to escape the winter conditions of their New York- and Chicago-based production locations. However, the advantages of production in southern California—particularly the varied landscapes in the region crucial for exterior, on-location photography—soon made Hollywood the dominant film production center in the country.i Hollywood, of course, is not synonymous with filmmaking in the United States. Before the early 1910s, American filmmaking was mostly New York-based, and specialized in the production of short films (circa 1909, a one-reel short, or approximately 10 minutes). At the time, French film companies dominated global film distribution, and it was more likely that one would see a French film in the United States than an American-produced one.