Skills Shortages in the Global Oil and Gas Industry How to Close the Gap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Success, Angola-Style

J. of Modern African Studies, 45, 4 (2007), pp. 595–619. f 2007 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0022278X07002893 Printed in the United Kingdom Business success,Angola-style: postcolonial politics and the rise and rise of Sonangol RICARDO SOARES DE OLIVEIRA Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford, Manor Road, Oxford OX1 3UQ, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper investigates a paradoxical case of business success in one of the world’s worst-governed states, Angola. Founded in 1976 as the essential tool of the Angolan end of the oil business, Sonangol, the national oil company, was from the very start protected from the dominant (both predatory and centrally planned) logic of Angola’s political economy. Throughout its first years, the pragmatic senior management of Sonangol accumulated technical and mana- gerial experience, often in partnership with Western oil and consulting firms. By the time the ruling party dropped Marxism in the early 1990s, Sonangol was the key domestic actor in the economy, an island of competence thriving in tandem with the implosion of most other Angolan state institutions. However, the grow- ing sophistication of Sonangol (now employing thousands of people, active in four continents, and controlling a vast parallel budget of offshore accounts and myriad assets) has not led to the benign developmental outcomes one would expect from the successful ‘capacity building’ of the last thirty years. Instead, Sonangol has primarily been at the service of the presidency and its rentier ambitions. Amongst other themes, the paper seeks to highlight the extent to which a nominal ‘failed state’ can be successful amidst widespread human destitution, provided that basic tools for elite empowerment (in this case, Sonangol and the means of coercion) exist to ensure the viability of incumbents. -

Massive and Misunderstood Data-Driven Insights Into National Oil Companies

Massive and Misunderstood Data-Driven Insights into National Oil Companies Patrick R. P. Heller and David Mihalyi APRIL 2019 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 1 I. UNDER-ANALYZED BEHEMOTHS ......................................................................................................... 6 II. THE NATIONAL OIL COMPANY DATABASE .....................................................................................10 III. SIZE AND IMPACT OF NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES .....................................................................15 IV. BENCHMARKING NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES BY VALUE ADDITION .....................................29 V. TRANSPARENCY AND NATIONAL OIL COMPANY REPORTING .................................................54 VI. CONCLUSIONS AND STEPS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH ............................................................61 APPENDIX 1. NOCs IN NRGI’S NATIONAL OIL COMPANY DATABASE ..........................................62 APPENDIX 2. CHANGES IN NOC ECONOMIC DATA AS REVENUES CHANGED..........................66 Key messages • National oil companies (NOCs) produce the majority of the world’s oil and gas. They dominate the production landscape in some of the world’s most oil-rich countries, including Saudi Arabia, Mexico, Venezuela and Iran, and play a central role in the oil and gas sector in many emerging producers. In 2017, NOCs that published data on their assets reported combined assets of $3.1 trillion. -

Resource V15 LIVE ANGOLA REPORT 0.Pdf

FEBRUARY 2011 OIL REVENUES IN ANGOLA MUCH MORE INFORMATION BUT NOT ENOUGH TRANSPARENCY GLOBAL WITNESS | OSISA ANGOLA | OIL REVENUES IN ANGOLA 2 Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa-Angola (OSISA-Angola): VISION: Building Vibrant and Tolerant Democracies in Southern Africa (Angola). MISSION: To promote societies that are open, tolerant, democratic, participatory and transparent and that respect and uphold the rule of law, freedom of the press and information, human rights and good governance. Global Witness Global Witness is a UK-based non-governmental organisation which investigates the role of natural resources in funding conflict and corruption around the world. References to Global Witness Note on the February 2011 edition: in this report are to Global Witness The first edition of this report, Limited, a company limited by published in December 2010, included guarantee and incorporated in a comparison between published England (Company No. 2871809) Angolan oil prices and an average value for Sonangol’s oil exports. This comparison has been removed from the new edition because it drew on data Global Witness Limited from Sonangol’s accounts which were Buchanan House based on technical cost estimates, not 30 Holborn on market prices, and were therefore London not comparable to market prices United Kingdom published by other entities. EC1N 2HS This edition also contains added points Email: [email protected] of information on the distinction between Sonangol’s oil exports as an agent of the Angolan state, and as a participant in concession agreements. GLOBAL WITNESS | OSISA ANGOLA | OIL REVENUES IN ANGOLA 3 CONTENTS Contents 9. How much money does Angola receive 37 from oil bonuses? Executive summary 4 9.a Signature bonuses 38 9.b Signature bonuses in 2006 38 Introduction 7 9.c “Social bonuses” 39 Why oil revenue transparency matters in Angola 7 9.d Sonangol’s reporting on bonuses in 2008 39 Are the Angolan government’s data reliable? 9 Systemic problems with the official data 10 10. -

OPEC Chief Says Oil Market Responding Well to Record OPEC+

May 21, 2020 OPEC chief says oil market responding well to "Chinese refiners have lost lots of money on refined oil record OPEC+ cut exports as demand in overseas markets was hit badly by the coronavirus," said Ding Xu of China-based Sublime OPEC is encouraged by a rally in oil prices and strong Info, adding that they would rather focus on the home adherence to its latest output cut, its secretary general market. said, although sources say the group has not ruled For the past two months, a complex refinery was losing out further steps to support the market. money producing gasoline as demand crashed following The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting lockdowns to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Countries, Russia and other allies, a group known as China's retail fuel prices are protected by a minimum Brent OPEC+, are cutting supply by a record 9.7 million crude price of $40 a barrel, however, and home demand barrels per day (bpd) from May 1 to offset a slump in has recovered swiftly, denting exports, said Kostantsa prices and demand caused by the coronavirus Rangelova of JBC Energy. outbreak. Expectations of lower Chinese petrol exports and optimism Oil prices have more than doubled since hitting a 21- over global demand recovery flipped Asia's refining margin year low below $16 in April. So far in May, OPEC+ to a small premium of 4 cents to Brent crude on Tuesday has cut oil exports by about 6 million bpd, according for the first time in about two months. -

Oiling Economic Growth and Development: Sonangol and the Governance of Oil Revenues in Angola

Development Planning Division Working Paper Series No. 21 Oiling economic growth and development: Sonangol and the governance of oil revenues in Angola George C Lwanda 2011 Development Planning Division Working Paper Series No. 21 Published by Development Planning Division Development Bank of Southern Africa PO Box 1234 Halfway House 1685 South Africa Telephone: +27 11 313 3048 Telefax: +27 11 206 3048 Email: [email protected] Intellectual Property and Copyright © Development Bank of Southern Africa Limited This document is part of the knowledge products and services of the Development Bank of Southern Africa Limited and is therefore the intellectual property of the Development Bank of Southern Africa. All rights are reserved. This document may be reproduced for non-profit and teaching purposes. Whether this document is used or cited in part or in its entirety, users are requested to acknowledge this source. Please use the suggested citation given above. Legal Disclaimer The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Development Bank of Southern Africa. Nor do they indicate that the DBSA endorses the views of the authors. In quoting from this document, users are advised to attribute the source of this information to the author(s) concerned and not to the DBSA. In the preparation of this document, every effort was made to offer the most current, correct and clearly expressed information possible. Nonetheless, inadvertent errors can occur, and applicable laws, rules and regulations may change. The Development Bank of Southern Africa makes its documentation available without warranty of any kind and accepts no responsibility for its accuracy or for any consequences of its use. -

Thirst for African

Thirst for African Oil: Asian National Oil Companies in Nigeria and Angola Alex Vines, Lillian Wong, Markus Weimer, Indira Campos Thirst for African Oil Asian National Oil Companies in Nigeria and Angola A Chatham House Report Alex Vines, Lillian Wong, Markus Weimer and Indira Campos Chatham House, 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0)20 7957 5700 E: [email protected] www.chathamhouse.org.uk F: +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration Number: 208223 Thirst for African Oil Asian National Oil Companies in Nigeria and Angola A Chatham House Report Alex Vines, Lillian Wong, Markus Weimer and Indira Campos www.chathamhouse.org.uk i www.chathamhouse.org.uk Chatham House has been the home of the Royal Institute of International Affairs for over eight decades. Our mission is to be a world-leading source of independent analysis, informed debate and influential ideas on how to build a prosperous and secure world for all. © Royal Institute of International Affairs, August 2009 Chatham House (the Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinion of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London, SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: +44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration No. -

Revitalising Oilfields Luanda's Arts Festival

SONANGOL UNIVERSO UISSUE 49 | APRILn 2016 iverso www.universo-magazine.com 40 Years of Success UPSTREAM CULTURE SOCIAL ACTION ISSUE 49 – REVITALISING LUANDA’S CHEVRON’S APRIL 2016 OILFIELDS ARTS FESTIVAL CSR EXPERIENCE Board president Francisco de Lemos José Maria at the anniversary event CONTENTS Universo is the international magazine of Sonangol President Francisco de Lemos José Maria Endiama Executive administrators: Anabela Soares de Brito da Fonseca, 4 3 NEWS BRIEFING Ana Joaquina Van-Dúnem Alves da Costa, Fernandes Gaspar Bernardo Mateus, Fernando Joaquim Roberto, A roundup of national and international news concerning Mateus Sebastião Francisco Neto, Sonangol and Angola Paulino Fernando Carvalho Jerónimo Non-executive administrators: Albina Assis Africano, José Gime, 4 André Lelo, José Paiva 10 3 PUMPING IS UP Sonangol Department for Communication & Image Director Angola output reaches 1.78 million bopd José Quarenta Mateus Cristóvão Benza SONANGOL: Shutterstock Corporate Communications Assistants Nadiejda Santos, Paula Almeida, FOUR DYNAMIC DECADES Hélder Sirgado, Kimesso Kissoka 12 3 SONANGOL RETROSPECTIVE Publisher: Sheila O’Callaghan he fortunes of Angola and Sonangol have been intimately Looking back on four decades of success 12 Editor: John Kolodziejski entwined over the past 40 years. Since its foundation on Managing Editor: Mauro Perillo February 25, 1976, the company has been the mainstay of T Shutterstock Art Director: Tony Hill the country’s economy. The oil industry that Sonangol leads so 22 3 WEATHERFORD WATCHING Sub Editor: Brian MacReamoinn dynamically has accounted for more than 90 per cent of export Profile of a leading oil services company Proofreading: Gail Nelson-Bonebrake earnings during the past four decades. -

Report and Consolidated 2017

MANAGEMENT REPORT AND CONSOLIDATED ACCOUNTS 2017 SUMMARY OF GENERAL INDEX 1 LETTER TO THE SHAREHOLDERS .......................................................................................................................................4 2 SONANGOL E.P. ...................................................................................................................................................................8 2.1 BUSINESS MODEL OF SONANGOL, E.P. .......................................................................................................................10 2.2 CORPORATE BODIES .....................................................................................................................................................14 3 PERFORMANCE SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................................................18 3.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................20 3.2 OPERATING PERFORMANCE – EBITDA ........................................................................................................................21 3.3 OPERATING PERFORMANCE – NET INCOME ................................................................................................................22 3.4 INVESTMENTS ..............................................................................................................................................................22 -

The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’S Extractive Industries

ACSS SPECIAL REPORT A PUBLICATION OF THE AFRICA CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’s Extractive Industries J.R. Mailey May 2015 The Africa Center for Strategic Studies The Africa Center is an academic institution established by the U.S. Department of Defense and funded by Congress for the study of security issues relating to Africa. It serves as a forum for bilateral and multilateral research, communication, and the exchange of ideas. The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’s Extractive Industries ACSS Special Report No. 3 J.R. Mailey May 2015 Africa Center for Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. The Africa Center would appreciate a courtesy copy of reprints or reviews. First printing, May 2015. For additional publications of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, visit the Center’s Web site at http://africacenter.org. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................1 Part 1: Africa’s Natural Resource Challenge ...........................................5 Natural Resource Wealth and -

Membership and IGU Marketing Plan

IGU Executive Committee Meeting in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 5 October 2009, Agenda item 4 IGU Council Meeting in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 5 October 2009, Agenda item 9 Membership and IGU Marketing Plan IGU Executive Committee Meeting in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 5 October 2009, Agenda item 4 IGU Council Meeting in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 5 October 2009, Agenda item 9 Part I: Membership 1. Charter Members Currently the number of Charter members is 72. The attached enclosure 1 gives the total list of Charter members. We are pleased to inform that Saudi Arabia has reconfirmed their Charter membership by Saudi Aramco. Unfortunately the Charter Member from Hungary has informed the Secretariat about their inten- tion of termination of IGU Membership as of 1 January 2010. This decision was based on reduc- tion of expenses of the Hungarian Gas Association. New Charter Members Sonangol Gás Natural (Sonagas), Angola Sonangol is a state owned company whose mission was the management of hydrocarbon resource exploration in Angola. Despite having the government as the sole shareholder, Sonangol has always been governed as a private company and is under strict performance standards to ensure efficiency and productivity. Focusing on diversifying its business activities, Sonangol has developed joint- ventures and established companies that promote both the social development of Angola and the expansion of Sonangol. Prioritizing the management of hydrocarbons, environmental protection and industrial safety, Sonangol has created a diversified business that is centred around oil and gas. More than 30 subsidiaries and joint venture companies are now part of Sonangol Group. In September 2004 Sonangol Natural Gás is created, as part of the Sonangol Group, with as main objective to explore, evaluate, produce, process, store, transport and to commercialize natural gas and its derivatives. -

National Oil Company Database Methodology Guide Updated December 2019

National Oil Company Database Methodology Guide Updated December 2019 Charlotte Huebner and Patrick R.P. Heller Contents I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Research process ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 A. SOURCES .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 B. SELECTION OF INDICATORS ........................................................................................................................................ 4 C. DEFINITION AND SELECTION OF NOCS....................................................................................................................... 6 III. Data gathering and interpretation decisions .............................................................................................................. 8 IV. Data challenges and mitigation approaches ............................................................................................................... 9 A. DATA AVAILABILITY .................................................................................................................................................... 9 B. DATA RELIABILITY ...................................................................................................................................................... -

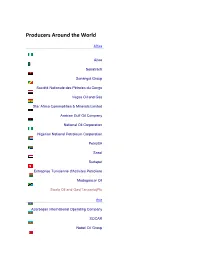

Producers Around the World

Producers Around the World Africa Aiteo Sonatrach Sonangol Group Société Nationale des Pétroles du Congo Vegas Oil and Gas Star Africa Commodities & Minerals Limited Arabian Gulf Oil Company National Oil Corporation Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation PetroSA Sasol Sudapet Entreprise Tunisienne d'Activites Petroliere Madagascar Oil Swala Oil and Gas(Tanzania)Plc Asia Azerbaijan International Operating Company SOCAR Nobel Oil Group Bahrain Petroleum Company Petrobangla Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise CEFC China Energy CNOOC China National Petroleum Corporation CITIC Resources Geo-Jade Petroleum Shaanxi Yanchang Petroleum Sinochem Sinopec Towngas United Energy Pakistan Gujarat State Petroleum Corporation Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Oil India Essar Oil Reliance Industries Cairn India MedcoEnergi Pertamina Energi Mega Persada National Iranian Oil Company National Iranian South Oil Company Iranian Central Oil Fields Company Iranian Offshore Oil Company North Oil Company South Oil Company Missan Oil Company Midland Oil Company Delek Isramco Modiin Energy Inpex JAPEX Nippon Oil KazMunayGas Kuwait Oil Company Consolidated Contractors Company Petronas Petroleum Development Oman Oil and Gas Development Company Pakistan Petroleum Pakistan Oilfields Mari Petroleum Company Limited Petron Corporation Philippine National Oil Company Qatar Petroleum Saudi Aramco KrisEnergy Singapore Petroleum Company Ceylon Petroleum Corporation Korea National Oil Corporation Korea Gas Corporation CPC Corporation PTT Thai Oil Türkiye Petrolleri Anonim Ortaklığı Çalık Enerji Abu Dhabi National Oil Company Emirates National Oil Company Uzbekneftegaz Petrovietnam Vietsovpetro Europe OMV RAG Petrol AD INA – Industrija Nafte Moravské naftové doly DONG Energy Atlantic Petroleum Total S.A. Engie DEA AG Wintershall Hellenic Petroleum MOL Group Maxol Anonima Petroli Italiana Edison Edoardo Raffinerie Garrone Eni Saras S.p.A.