PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Peoples/Ethnic Minorities and Poverty Reduction: Regional Report

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES/ETHNIC MINORITIES AND POVERTY REDUCTION REGIONAL REPORT Roger Plant Environment and Social Safeguard Division Regional and Sustainable Development Department Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines June 2002 © Asian Development Bank 2002 All rights reserved Published June 2002 The views and interpretations in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asian Development Bank. ISBN No. 971-561-438-8 Publication Stock No. 030702 Published by the Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980, Manila, Philippines FOREWORD his publication was prepared in conjunction with an Asian Development Bank (ADB) regional technical assistance (RETA) project on Capacity Building for Indigenous Peoples/ T Ethnic Minority Issues and Poverty Reduction (RETA 5953), covering four developing member countries (DMCs) in the region, namely, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, and Viet Nam. The project is aimed at strengthening national capacities to combat poverty and at improving the quality of ADB’s interventions as they affect indigenous peoples. The project was coordinated and supervised by Dr. Indira Simbolon, Social Development Specialist and Focal Point for Indigenous Peoples, ADB. The project was undertaken by a team headed by the author, Mr. Roger Plant, and composed of consultants from the four participating DMCs. Provincial and national workshops, as well as extensive fieldwork and consultations with high-level government representatives, nongovernment organizations (NGOs), and indigenous peoples themselves, provided the basis for poverty assessment as well as an examination of the law and policy framework and other issues relating to indigenous peoples. Country reports containing the principal findings of the project were presented at a regional workshop held in Manila on 25–26 October 2001, which was attended by representatives from the four participating DMCs, NGOs, ADB, and other finance institutions. -

11 Cambodia's Highlanders

1 1 CAMBODIA’S HIGHLANDERS Land, Livelihoods, and the Politics of Indigeneity Jonathan Padwe Throughout Southeast Asia, a distinction can be made between the inhabitants of lowland “state” societies and those of remote upland areas. This divide between hill and valley is one of the enduring social arrangements in the region—one that organizes much research on Southeast Asian society (Scott 2009). In Cambodia, highland people number some 200,000 individuals, or about 1.4 percent of the national population of approximately 15 million (IWGIA 2010). Located in the foothills of the Annamite Mountains in Cambodia’s northeast highlands, in the Cardamom Mountains to the southwest and in several other small enclaves throughout the country, Cambodia’s highland groups include, among others, the Tampuan, Brao, Jarai, Bunong, Kuy, and Poar. These groups share in common a distinction from lowland Khmer society based on language, religious practices, livelihood practices, forms of social organization, and shared histories of marginalization. This chapter provides an overview of research and writ- ing about key issues concerning Cambodia’s highlanders. The focus is on research undertaken since the 1992–1993 United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), when an improved security situation allowed for a resumption of research with and about highland people. Important areas of concern for research on the highlands have included questions about highlanders’ experience of war and genocide, environmental knowledge, access to land and natural resources and problems of “indigeneity” within the politics of identity and ethnicity in Cambodia. Early ethnography of the highlands The earliest written records of highland people in the region are ninth- to twelfth-century inscriptions from the Po Nagar temple near present-day Phan Rang, in Vietnam, which describe the conquests of Cham rulers “against the Radé, the Madas [Jarai], and other barbarians” (Schweyer 2004, 124). -

The Silent Emergency

Master Thesis The silent emergency: ”You are what you eat!‘ (The perceptions of Tampuan mothers about a healthy well nourished body in relationship to their daily food patterns and food habits) Ratanakiri province Cambodia Margriet G. Muurling-Wilbrink Amsterdam Master‘s in Medical Anthropology Faculty of Social & Behavioural Sciences Universiteit van Amsterdam Supervisor: Pieter Streefland, Ph.D. Barneveld 2005 The silent emergency: ”You are what you eat!‘ 1 Preface ”I am old, my skin is dark because of the sun, my face is wrinkled and I am tired of my life. You are young, beautiful and fat, but I am old, ugly and skinny! What can I do, all the days of my life are the same and I do not have good food to eat like others, like Khmer people or Lao, or ”Barang‘ (literally French man, but used as a word for every foreigner), I am just Tampuan. I am small and our people will get smaller and smaller until we will disappear. Before we were happy to be smaller, because it was easier to climb into the tree to get the fruit from the tree, but nowadays we feel ourselves as very small people. We can not read and write and we do not have the alphabet, because it got eaten by the dog and we lost it. What should we do?‘ ”We do not have the energy and we don‘t have the power to change our lives. Other people are better than us. My husband is still alive, he is working in the field and he is a good husband, because he works hard on the field. -

Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: Phd

Access to Electronic Thesis Author: Lonán Ó Briain Thesis title: Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: PhD This electronic thesis is protected by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No reproduction is permitted without consent of the author. It is also protected by the Creative Commons Licence allowing Attributions-Non-commercial-No derivatives. If this electronic thesis has been edited by the author it will be indicated as such on the title page and in the text. Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain May 2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music University of Sheffield © 2012 Lonán Ó Briain All Rights Reserved Abstract Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain While previous studies of Hmong music in Vietnam have focused solely on traditional music, this thesis aims to counteract those limited representations through an examination of multiple forms of music used by the Vietnamese-Hmong. My research shows that in contemporary Vietnam, the lives and musical activities of the Hmong are constantly changing, and their musical traditions are thoroughly integrated with and impacted by modernity. Presentational performances and high fidelity recordings are becoming more prominent in this cultural sphere, increasing numbers are turning to predominantly foreign- produced Hmong popular music, and elements of Hmong traditional music have been appropriated and reinvented as part of Vietnam’s national musical heritage and tourism industry. Depending on the context, these musics can be used to either support the political ideologies of the Party or enable individuals to resist them. -

IPDF: Regional: Greater Mekong Subregion Biodiversity

Greater Mekong Subregion Biodiversity Conservation Corridors Project (RRP REG 40253) SUMMARY OF THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES1 DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK A. Project Description 1. The expected impact of the investment project is for climate resilient transboundary biodiversity conservation corridors sustaining livelihoods and investments in Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Viet Nam. As an outcome of the investment project, it is envisaged that by 2018, GMS Biodiversity Conservation Corridors are established with supportive policy and regulatory framework in Cambodia, Lao PDR and Viet Nam maintaining ecosystem connectivity and services. The project includes measures for (i) Institutional and community strengthening for biodiversity corridor management, (ii) Biodiversity corridors restoration, ecosystem services protection, and sustainable management by local resource managers, (iii) Livelihood improvement and small scale infrastructure support in target villages and communes, and (iv) Project management and support services. 2. BCI 2 builds on experiences of Phase I that has been assessed to be a pro-poor, pro- indigenous peoples project focused on remote mountain areas. Under BCI 2, biodiversity corridors or multiple use areas will allow for current, existing forest blocks as allocated by the three Governments to remain protected as they are under various status of state protection. Connectivity between forest-blocks will be restored as a result of broad community support generated through appropriate consultation and participation modalities. Stakeholder guidance will be imperative for establishment of i) linear forest links or ii) stepping stone forest blocks to establish connectivity in the corridors. 3. Intensive capacity building across project cycle, and ensuring broad community support in subproject prioritization, planning, selection, and implementation will be observed. -

Photo by Chan Sokheng.

(Photo by Chan Sokheng.) Livelihoods in the Srepok River Basin in Cambodia: A Baseline Survey Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ii Acknowledgements iii Map of the Srepok River Basin iv Map of the Major Rivers of Cambodia v Executive Summary vi 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Methodology 1 1.2 Scope and limitations 3 2. The Srepok River and Tributaries 4 3. Protected Areas 7 4. Settlement and Ethnicity 8 5. Land and the Concept of Village 12 6. Water Regime 14 7. Transport 17 8. Livelihoods 19 8.1 Lowland (wet) rice cultivation 19 8.2 Other cultivation of crops 22 8.3 Animal raising 25 8.4 Fishing 27 8.5 Wildlife collection 42 8.6 Collection of forest products 43 8.7 Mining 47 8.8 Tourism 49 8.9 Labor 49 8.10 Water supply 50 8.11 Health 51 9. Implications for Development Practitioners and Directions for Future Research 52 Annex 1. Survey Villages and Ethnicity 55 Annex 2. Data Collection Guides Used During Fieldwork 56 Annex 3. Maximum Sizes (kg) of Selected Fish Species Encountered in Past Two Years 70 References 71 i Livelihoods in the Srepok River Basin in Cambodia: A Baseline Survey List of Figures and Tables Figure 1: Map of the Srepok basin in Cambodia and target villages 2 Figure 2: Rapids on the upper Srepok 4 Figure 3: Water levels in the Srepok River 4 Figure 4: The Srepok River, main tributaries, and deep-water pools on the Srepok 17 Figure 5: Protected areas in the Srepok River basin 7 Figure 6: Ethnic groups in the Srepok River basin in Cambodia 11 Figure 7: Annual spirit ceremony in Chi Klap 12 Figure 8: Trends in flood levels 14 Figure 9: Existing and proposed hydropower dam sites within the basin 15 Figure 10: Road construction, Pu Chry Commune (Pech Roda District, Mondulkiri) 17 Figure 11: Dikes on tributaries of the Srepok 21 Figure 12. -

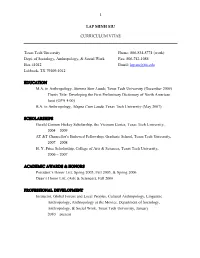

LAP MINH SIU CURRICULUM VITAE Texas Tech University Phone: 806

1 LAP MINH SIU CURRICULUM VITAE Texas Tech University Phone: 806-834-8774 (work) Dept. of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work Fax: 806-742-1088 Box 41012 Email: [email protected] Lubbock, TX 79409-1012 EDUCATION M.A. in Anthropology, Summa Sum Laude, Texas Tech University (December 2009) Thesis Title: Developing the First Preliminary Dictionary of North American Jarai (GPA 4.00) B.A. in Anthropology, Magna Cum Laude, Texas Tech University (May 2007) SCHOLARSHIPS Gerald Cannon Hickey Scholarship, the Vietnam Center, Texas Tech University, 2004 – 2009 AT &T Chancellor’s Endowed Fellowship, Graduate School, Texas Tech University, 2007 – 2008 H. Y. Price Scholarship, College of Arts & Sciences, Texas Tech University, 2006 – 2007 ACADEMIC AWARDS & HONORS President’s Honor List, Spring 2005, Fall 2005, & Spring 2006 Dean’s Honor List, (Arts & Sciences), Fall 2006 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Instructor, Global Forces and Local Peoples, Cultural Anthropology, Linguistic Anthropology, Anthropology at the Movies. Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, January 2010 – present 2 Research Assistant/Language Consultant (Jarai). Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, June 2007 – December 2009 Collaborating on development of descriptive and pedagogical grammar of Jarai language – an indigenous language of Vietnam and spoken by over 3000 refugees in the United States and Canada. Jarai-Rhade Language Fonts Consultant. Linguist’s Software, Inc., July – September 2008 Assisted with the development and implementation of fonts for the Jarai and Rhade languages (www.linguistsoftware.com). Student/Language Consultant (Jarai). The Vietnam Center and Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, January – May 2007 Collaborating on development of descriptive and pedagogical grammar of Jarai language – an indigenous language of Vietnam and spoken by over 3000 refugees in the United States and Canada. -

GAPE Newsletter-Vol. 4 #4-Spring 2006.Doc

The Global Association for People and the Environment (GAPE) Newsletter Vol. 4 # 4 Spring 2006 “Helping People in an Environmentally Friendly Way, Helping the Environment in a People Friendly Way.” GAPE Organises Study Trip to Champasak Province, Southern Laos for Ethnic Brao People from Ratanakiri Province, Northeast Cambodia By Ian G. Baird Accomplished master musician Phon Dao, an ethnic Kreung (a Brao sub-group) man playing a traditional Brao melody on a ‘mem’ . We are sorry to report that in April 2006, just two weeks after returning to Ratanakiri, Cambodia from performing traditional music in Brao villages in Champasak province, Laos, Phon Dao passed away. (photo by M. Sly) In 2005 GAPE arranged for 11 ethnic Brao people from Pathoumphone district, Champasak province to visit Brao villages in Ratanakiri province, northeast Cambodia. In 2006 GAPE organised a reciprocal visit of 12 Brao people from Ratanakiri province to Champasak province. The group was in Laos from late March until early April 2006, and had the chance to visit seven ethnic Brao villages and one ethnic Nya Heun village. Ian Baird and Ethnic Culture officer Khampanh Keovilaysak led the group. The Brao from Cambodia and the Brao from Laos had the chance to meet and exchange information about relatives and various other topics, including protected area management, music, cultural protection, swidden agriculture tree plantations and land protection. The Brao from Cambodia were especially impressed to find that ethnic Brao people in Laos are allowed to reside in protected areas, like Xe Pian National Protected Area, and that they have considerable rights and responsibilities in terms of natural resource management compared to the more centralized protected area management in Cambodia. -

Behind the Lens

BEHIND THE LENS Synopsis On the banks of the Mekong, where access to education is a daily struggle, six children of different ages dream of a better future. Like the pieces of a puzzle, the paths taken by Prin, Myu Lat Awng, Phout, Pagna, Thookolo and Juliet fit together to tell the amazing story of WHEN I GROW UP. WHEN I GROW UP is first and foremost a story of a coming together. A coming together of a charity, Children of the Mekong, which has been helping to educate disadvantaged children since 1958; with a committed audio-visual production company, Aloest; with a film director, Jill Coulon, in love with Asia and with stories with a strong human interest; with a pair of world-famous musicians, Yaël Naïm and David Donatien. These multiple talents have collaborated to produce a wonderful piece of cinema designed to inform as many people as possible of the plight of these children and of the benefits of getting an education. Find out more at www.childrenofthemekong.org Credits: A film by Jill Coulon Produced by François-Hugues de Vaumas and Xavier de Lauzanne Director: Jill Coulon Assistant Director: Antoine Besson Editing: Daniel Darmon Audio mixing: Eric Rey Colour grading: Jean-Maxime Besset Music : Yaël Naïm and David Donatien Subtitles: Raphaële Sambardier Translation: Garvin Lambert Graphic design: Dare Pixel Executive Production Company: Aloest films Associate Production Company: Children of the Mekong INTERVIEW WITH THE DIRECTOR Jill Coulon A professional film director with a passion for all things Asia, Jill Coulon put her talent at the disposal of the six narrators of WHEN I GROW UP so they could tell their stories to an international audience. -

Vietnam: Torture, Arrests of Montagnard Christians Cambodia Slams the Door on New Asylum Seekers

Vietnam: Torture, Arrests of Montagnard Christians Cambodia Slams the Door on New Asylum Seekers A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper January 2005 I. Introduction ..........................................................................................................2 II. Recent Arrests and harassment ...........................................................................5 Arrests of Church Leaders and Suspected Dega Activists.................................. 6 Detention of Families of Refugees...................................................................... 7 Mistreatment of Returnees from Cambodia ........................................................ 8 III. Torture and abuse in Detention and police custody.........................................13 Torture of Suspected Activists .......................................................................... 13 Mistreatment of Deportees from Cambodia...................................................... 15 Arrest, Beating, and Imprisonment of Guides for Asylum Seekers.................. 16 IV. The 2004 Easter Crackdown............................................................................18 V. Religious Persecution........................................................................................21 Pressure on Church Leaders.............................................................................. 21 VI. New Refugee Flow ..........................................................................................22 VII. Recommendations ..........................................................................................24 -

The Plight of the Montagnards,” Hearing Before the Committee of Foreign Relations United States Senate, One Hundred Fifth Congress, Second Session (Washington DC: U.S

Notes 1 Introduction and Afterword 1. Senator Jesse Helms, “The Plight of the Montagnards,” Hearing Before The Committee Of Foreign Relations United States Senate, One Hundred Fifth Congress, Second Session (Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, March 10, 1988), 1, http://frwebgate. access.gpo.gov/cg...senate_hearings&docid=f:47 64.wais, 10-5-99. 2. Ibid., 3. 3. Y’Hin Nie, in ibid., 24. 4. The word “Dega” is used by the refugees in both singular and plural constructions (e.g., “A Dega family arrived from Vietnam this week,” as well as “Many Dega gathered for church.”). 5. For a recent analysis of the historical emergence of names for popula- tion groups in the highlands of Southeast Asia, including the central highlands of Vietnam, see Keyes, “The Peoples of Asia,” 1163–1203. 6. There are no published studies of the Dega refugee community, but see: Cecily Cook, “The Montagnard-Dega Community of North Carolina” (University of North Carolina: MA Thesis in Folklore Studies, 1994); Cheyney Hales and Kay Reibold, Living in Exile, Raleigh (a film pro- duced by the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1994); and David L. Driscoll, “We Are the Dega: Ethnic Identification in a Refugee Community” (Wake Forest University: MA Thesis in Anthropology, 1994). Studies of the Hmong include: Robert Downing and D. Olney, eds., The Hmong in the West (Minneapolis: Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, 1982); Shelly R. Adler, “Ethnomedical Pathogenesis and Hmong Immigrants’ Sudden Nocturnal Deaths,” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 18 (1994): 23–59; Kathleen M. McInnis, Helen E. Petracchi, and Mel Morgenbesser, The Hmong in America: Providing Ethnic-Sensitive Health, Education, and Human Services (Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1990); and Anne Fadiman, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998). -

Ÿþh I S O R I C a L I M a G I N a T I O N , D I a S P O R I C I D E N T I T Y a N D I

Historical Imagination, Diasporic Identity And Islamicity Among The Cham Muslims of Cambodia by Alberto Pérez Pereiro A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved November 2012 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Hjorleifur Jonsson, Co-Chair James Eder, Co-Chair Mark Woodward ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2012 ABSTRACT Since the departure of the UN Transitional Authority (UNTAC) in 1993, the Cambodian Muslim community has undergone a rapid transformation from being an Islamic minority on the periphery of the Muslim world to being the object of intense proselytization by foreign Islamic organizations, charities and development organizations. This has led to a period of religious as well as political ferment in which Cambodian Muslims are reassessing their relationships to other Muslim communities in the country, fellow Muslims outside of the country, and an officially Buddhist state. This dissertation explores the ways in which the Cham Muslims of Cambodia have deployed notions of nationality, citizenship, history, ethnicity and religion in Cambodia’s new political and economic climate. It is the product of a multi-sited ethnographic study conducted in Phnom Penh and Kampong Chhnang as well as Kampong Cham and Ratanakiri. While all Cham have some ethnic and linguistic connection to each other, there have been a number of reactions to the exposure of the community to outside influences. This dissertation examines how ideas and ideologies of history are formed among the Cham and how these notions then inform their acceptance or rejection of foreign Muslims as well as of each other. This understanding of the Cham principally rests on an appreciation of the way in which geographic space and historical events are transformed into moral symbols that bind groups of people or divide them.