Deconstructing the First Order/Second Order Distinction in Face And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Order 12985— Establishing the Armed Forces Service Medal

62 Jan. 12 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 1996 received in time for publication in the appropriate suitable device may be awarded to be worn issue. on the medal or ribbon as prescribed by ap- propriate regulations. Sec. 4. Posthumous Provision. The medal Executive Order 12985Ð may be awarded posthumously and, when so Establishing the Armed Forces awarded, may be presented to such rep- Service Medal resentative of the deceased as may be January 11, 1996 deemed appropriate by the Secretary of De- fense or the Secretary of Transportation. By the authority vested in me as President William J. Clinton by the Constitution and the laws of the Unit- ed States of America, including my authority The White House, as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces January 11, 1996. of the United States, it is hereby ordered as [Filed with the Office of the Federal Register, follows: 8:45 a.m., January 17, 1996] Section 1. Establishment. There is hereby established the Armed Forces Service Medal NOTE: This Executive order was released by the with accompanying ribbons and appur- Office of the Press Secretary on January 13, and it was published in the Federal Register on Janu- tenances, for award to members of the ary 18. Armed Forces of the United States who, on or after June 1, 1992, in the opinion of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: (a) Participate, or have Remarks to American Troops at participated, as members of United States Aviano Air Base, Italy military units in a United States military op- January 13, 1996 eration in which personnel of any Armed Force participate that is deemed to be signifi- The President. -

Undergraduate Degree Fields

Chapter: 2/Postsecondary Education Section: Programs, Courses, and Completions Undergraduate Degree Fields In 2017–18, over two-thirds of the 1.0 million associate’s degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions were concentrated in three fields of study: liberal arts and sciences, general studies, and humanities (398,000 degrees); health professions and related programs (181,000 degrees); and business (118,000 degrees). Of the 2.0 million bachelor’s degrees conferred in 2017–18, more than half were concentrated in five fields of study: business (386,000 degrees); health professions and related programs (245,000 degrees); social sciences and history (160,000 degrees); engineering (122,000 degrees); and biological and biomedical sciences (119,000 degrees). In academic year 2017–18, postsecondary institutions were the following: homeland security, law enforcement, conferred 1.0 million associate’s degrees. Over two- and firefighting (3 percent, or 35,300 degrees); computer thirds (69 percent) of these degrees were concentrated and information sciences and support services (3 percent, in three fields of study: liberal arts and sciences, general or 31,500 degrees); and multi/interdisciplinary studies2 studies, and humanities (39 percent, or 398,000 degrees); (3 percent, or 31,100 degrees). Overall, 85,300 associate’s health professions and related programs (18 percent, or degrees or certificates (8 percent) were conferred in 181,000 degrees); and business1 (12 percent, or 118,000 science, technology, engineering, and mathematics degrees). -

Labor Commissioner's Office

ASSIGNING YOUR THINGS TO REMEMBERLEGALFAQs TERMS TO JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT (ENGLISH) HELP YOU COLLECT JUDGMENT TO THE LABOR YOUR AWARD COMMISSIONER’S OFFICE The Labor ODA: Order, Decision or Award states the Labor The Labor Commissioner helps some workers collect their awards. ☐ Stay organized. Keep all your documents in one place, 1. What if my employer files for Commissioner’s Commissioner’s decision on your claim for unpaid wages and If this option is available to you, you will receive a form called and keep a journal of everything you have done to bankruptcy? the amount the employer must pay, if any. “Assignment of Judgment” to sign in person at any of the Labor collect your judgment. If you receive notice that your employer has filed for Offi ce, Commissioner’s offices or to have notarized. If you agree to assign PLAINTIFF & DEFENDANT: The court generally refers to wage bankruptcy, you can no longer file liens or use levies your judgment to the Labor Commissioner, you can no longer try ☐ Follow instructions for all court forms, and make claimants as plaintiffs and employers as defendants. Plaintiffs make a to collect your judgment. Instead, you must follow also called the Division of Labor Standards to collect the judgment on your own. If the Labor Commissioner copies of all forms before you submit them. legal claim that a defendant has violated the law. the bankruptcy court’s process for collecting your cannot assist you to collect your ODA amount, you will receive a Enforcement (DLSE), is part of the California ☐ On all forms, you are always the “creditor” and judgment, along with your employer’s other creditors. -

Articles of Chivalry

TThhee AArrttiicclleess ooff CChhiivvaallrryy We as Chivalric Knights of the Holy Order of the Fellow Soldiers of Jacques DeMolay, as we affix our signatures to this set of articles, do hereby agree to uphold them as a covenant upon which we wish to base our lives as Sir Knights. We further recognize that through the incorporation of these articles into our lives, we can better represent ourselves and the Order of DeMolay. We further assert our willingness to be removed from the roles of Knighthood should it ever be found that our conduct has been contrary to the principles herein set. Article 1 - A Sir Knight is Honorable 1. A Sir Knight must accept responsibility for the one thing that is within his control: himself. 2. A Sir Knight must always keep his word, realizing that a man who's word is as good as his bond is held in high esteem by all. 3. A Sir Knight must never speak harshly or critically of a Brother, unless it be in private and tempered with the love one Brother has for another, always speaking to him for the purpose of aiding him to be a better man. 4. A Sir Knight must always rely on his instincts and those lessons taught to him throughout the course of his DeMolay career when deciding right from wrong. Article 2 - A Sir Knight Shows Excellence 1. A Sir Knight must commit to excellence, and seek the highest level of excellence in all aspects of his life. 2. A Sir Knight must always excel in his education, putting forth his best effort in all his school works. -

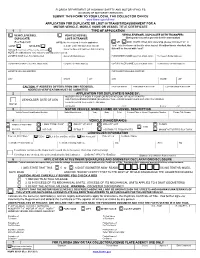

Application for Duplicate Or Lost in Transit / Reassignment for a Motor

FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF HIGHWAY SAFETY AND MOTOR VEHICLES DIVISION OF MOTORIST SERVICES SUBMIT THIS FORM TO YOUR LOCAL TAX COLLECTOR OFFICE www.flhsmv.gov/offices/ APPLICATION FOR DUPLICATE OR LOST IN TRANSIT/REASSIGNMENT FOR A MOTOR VEHICLE, MOBILE HOME OR VESSEL TITLE CERTIFICATE 1 TYPE OF APPLICATION VEHICLE/VESSEL VEHICLE/VESSEL VEHICLE/VESSEL DUPLICATE WITH TRANSFER: (Both parties must be present for this transaction) DUPLICATE: LOST IN TRANSIT: (Fee Required) NOTE: No fee required if vehicle application OR AND NOTE: When joint ownership, please indicate if “or” or is made within 180 days from last title “and” is to be shown on the title when issued. If neither box is checked, the LOST STOLEN title will be issued with “and”. Damaged (Certificate of Title must be submitted) issuance date and has been lost in mailing. NOTE: An indication of lost, stolen or damaged is required. OWNER’S NAME (Last, First, Middle Initial) Owner’s E-Mail Address PURCHASER’S NAME (Last, First, Middle Initial) Purchaser’s E-Mail Address CO-OWNER’S NAME (Last, First, Middle Initial) Co-Owner’s E-Mail Address CO-PURCHASER’S NAME (Last, First, Middle Initial) Co-Purchaser’s E-Mail Address OWNER’S MAILING ADDRESS PURCHASER’S MAILING ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CITY STATE ZIP DATE OF BIRTH PURCHASER’S DL/ID # CO-PURCHASER’S DL/ID# CAUTION: IF ADDRESS DIFFERS FROM DMV RECORDS, ADDRESS VERIFICATION MUST BE SUBMITTED 2 APPLICATION FOR DUPLICATE IS MADE BY: MOTOR VEHICLE MOBILE HOME OR RECREATIONAL VEHICLE DEALER/ DEALER/AUCTION LICENSE NUMBER DOES NOT APPLY TO VESSELS: -

The Purple Heart

The Purple Heart It is one of the most recognized and respected medals awarded to members of the U.S. armed forces. Introduced as the “Badge of Military Merit” by General George Washington in 1782, the Purple Heart is also the nation’s oldest military award. In military terms, the award had “broken service,” as it was ignored for nearly 150 years until it was re-introduced on February 22, 1932, on the 200th anniversary of George Washington’s birth. The medal’s plain inscription “FOR MILITARY MERIT” barely expresses its significance. --------------------------------- On August 7, 1782, from his headquarters in Newburgh, New York, General George Washington wrote: “The General ever desirous to cherish virtuous ambition in his soldiers, as well as to foster and encourage every species of Military merit, directs that whenever any singularly meritorious action is performed, the author of it shall be permitted to wear on his facings over the left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth, or silk, edged with narrow lace or binding. Not only instances of unusual gallantry, but also of extraordinary fidelity and essential Gen. George Washington’s instructions for service in any way shall meet with a due the Badge of Military Merit reward. Before this favour can be conferred on any man, the particular fact, or facts, on which it is to be grounded must be set forth to the Commander in chief accompanied with certificates from the Commanding officers of the regiment and brigade to which the Candidate for reward belonged, or other incontestable proofs, and upon granting it, the name and regiment of the person with the action so certified are to be enrolled in the book of merit which will be kept at the orderly office. -

Definitions: Fellow/Resident: a Physician Who Is Engaged in A

Roles, Responsibilities and Patient Care Activities of Fellows ADOLESCENT MEDICINE FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM Definitions: Fellow/Resident: A physician who is engaged in a graduate training program in medicine (which includes all specialties) and who participates in patient care under the direction of attending physicians (or licensed independent practitioners) as approved by each review committee. Note: The term “resident” may also be used interchangeably with fellow for training and includes all residents and fellows including individuals in their first year of training (PGY1), often referred to as “interns,” and individuals in approved subspecialty graduate medical education programs who historically have also been referred to as “fellows.” As part of their training program, fellows are given graded and progressive responsibility according to the individual fellow’s clinical experience, judgment, knowledge, and technical skill. Each fellow must know the limits of his/her scope of authority and the circumstances under which he/she is permitted to act with conditional independence. Fellows are responsible for asking for help from the supervising physician (or other appropriate licensed practitioner) for the service they are rotating on when they are uncertain of diagnosis, how to perform a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure, or how to implement an appropriate plan of care. Attending of Record (Attending) An identifiable, appropriately-credentialed and privileged attending physician or licensed practitioner (as approved by each Review Committee) who is ultimately responsible for the management of the individual patient and for the supervision of the fellows involved in the care of the patient, The attending delegates portion of care to fellow based on the needs of the patient and the skills of the fellow. -

Court Order Packet and Instructions

STEPS TO OBTAINING A COURT ORDERED CERTIFICATE OF TITLE Step Where To Go STEPS TO COMPLETE • Complete BMV 1173 Form and check the box “Last Known Address” and “Copy of Record” for the vehicle owner and remit the form to the BMV using the instructions provided on the form. The BMV will mail a BMV 2433 form to : you containing the results of the record search. • One BMV 1173 forms are available online at www.bmv.ohio.gov or by calling (614) 752-7671 Step (614) 752-7671 • A $5.00 record search fee will apply for each www.bmv.ohio.gov title record search. • Please allow at least 15 business days for processing. Vehicle Owner Record Search Record Owner Vehicle • Please retain BMV 2433 form to file with your petition as a necessary exhibit. • Mail a certified letter to the vehicle owner(s) and lien holder(s) using information provided by the BMV and Auto Title Division notifying them : of your intention to petition the Court for wo Certificate of Title. www.usps.gov • Please retain copies of the letters mailed as well Step T as the returned certified mail receipts to file Notifications Certified Mail Mail Certified with your petition as a necessary exhibit. • Please allow 15 days from the date of mailing for appropriate parties to respond. • Visit your local deputy registrar office to purchase an OSHP Inspection Receipt (HP105) : • The cost for the OSHP Inspection Receipt is $53.50. Three • Visit www.bmv.ohio.gov or call (614) 752-7671 for your nearest deputy registrar location. -

Displaying Your Credentials Proudly and Properly

National Certification Commission ® for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine Displaying Your Credentials Proudly and Properly By Kory Ward-Cook, Ph.D., CAE, MT (ASCP), Chief Executive Officer and Mina Larson, M.S., Deputy Director of NCCAOM One thing for certain about the credentials is a personal one. In most in the issuing state. Using the case above, acupuncture and Oriental medicine cases, one should list the lowest to the if Joe Smith is a licensed acupuncturist, (AOM) community is the number of highest degree earned, such as “Mary typically his designations would be impressive credentials that many AOM Smith, M.S., Ph.D.”. The preferred method displayed as Joe Smith, D.O.M., MBA, practitioners hold. Judging from the is to list only the highest academic degree, L.Ac. (or other similar designation). variety of ways these credentials are for example, only the Ph.D. even though Some states have also protected the titles displayed on business cards, publications, you may have earned a Masters degree they use in their regulations or statutes, and everywhere else, there is much as well. If you have also earned a Masters such as doctor of Oriental medicine confusion about how to use and list (M.S., MOM, MBA, etc.); however, you (D.O.M.). Although these titles are credentials correctly. AOM practitioners may want to highlight it if the degree is recognized for licensure, you cannot who devote years to earning their important to your career at the current use a protected credential in that state credentials should proudly display them; time. For example, you may have a D.O.M. -

Quiet Title Statute

QUIET TITLE STATUTE K.S.A. 60-1002: Quieting or determining title or interest in property (a) Right of action An action may be brought by any person claiming title or interest in personal or real property, including oil and gas leases, mineral or royalty interests, against any person who claims an estate or interest therein adverse to him or her, for the purpose of determining such adverse claim. (b) Action to bar lien claim, when When a lien on property has ceased to exist, or when an action to enforce a lien is barred by a statute of limitation or otherwise, the owner of the property may maintain an action to quiet title. RELATING TO PERSONAL PROPERTY, SUCH AS CARS, TRAVEL TRAILERS, MANUFACTURED HOMES(may also be known as mobile homes or trailers), ETC. When a person or business applies for a title with the Division of Motor Vehicles (DMV), there may be a problem that needs to be fixed. Often this is because the initial owner of the vehicle did not sign the title when handing it over to the new owner, and the new owner can’t find the person to fix the problem. From time to time it is because a wrecked or abandoned vehicle is restored and the owner can’t be found. These are just a couple of possible reasons. To fix these snags, you would file a QUIET TITLE ACTION /CASE. If you need to transfer a vehicle belonging to a family member who is deceased, you can do so with these forms: http://www.ksrevenue.org/pdf/tr83.pdf or http://www.ksrevenue.org/pdf/tr83b.pdf if either is proper. -

Higher-Order Modules and the Phase Distinction

Higher-Order Modules and the Phase Distinction Robert Harper1 John C. Mitchell2 Eugenio Moggi3 October 1989 CMU-CS-89-197 School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 This report is an expanded version of a paper to be presented at the 17th Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages, San Francisco, CA, January, 1990. 1Supported by the Office of Naval Research under contract N00014-84-K-0415 and by the Defense Ad- vanced Research Projects Agency (DOD), ARPA Order No. 5404, monitored by the Office of Naval Research under the same contract. 2Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. Partially supported by an NSF PYI Award, matching funds from Digital Equipment Corporation, Xerox Corporation and the Powell Foundation and by NSF grant CCR-8814921. 3University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3QG, UK. Supported by ESPRIT Basic Research Action No. 3003, Categorical Logic In Computer Science. Abstract In earlier work, we used a typed function calculus, XML, with dependent types to analyze several aspects of the Standard ML type system. In this paper, we introduce a refinement of XML with a clear compile-time/run-time phase distinction, and a direct compile-time type checking algorithm. The calculus uses a finer separation of types into universes than XML and enforces the phase distinction using a nonstandard equational theory for module and signature expressions. While unusual from a type-theoretic point of view, the nonstandard equational theory arises naturally from the well-known Grothendieck construction on an indexed category. 1 Introduction The module system of Standard ML [HMM86] provides a convenient mechanism for factor- ing ML programs into separate but interrelated program units. -

19101 Through the Supporting Installation

Department of the Army – Medal of Heroism Medal of Heroism Medal of Heroism, is a U.S. military decoration awarded by the Department of the Army (DA) to a JROTC cadet who performs an act of heroism. The achievement must be an accomplishment so exceptional and outstanding that it clearly sets the individual apart from fellow students or from other persons in similar circumstances. The performance must have involved the acceptance of danger and extraordinary responsibilities, exemplifying praiseworthy fortitude and courage. Nominations will be: • Initiated by the SAI based on achievements described in a above. Such acts may have been accomplished while on or off the institution property. • Submitted by the SAI to the appropriate subordinate commander concerned for approval or disapproval. A DA Form 638 (Recommendation for Award) or a letter will be used. Statements of eyewitnesses (preferably in the form of certificates, affidavits, or sworn statements), extracts from official records, sketches, maps, diagrams, or photographs will be attached to support and amplify stated facts. The final approval authority is the Brigade Commander. Requisitions for the medals may be submitted to Defense Personnel Support Center, ATTN: DPSC–T, 2800 South 20th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19101 through the supporting installation. Presentation of this award will be made during an appropriate ceremony by a general officer or other senior officer of the Active Army. Department of the Army – Superior JROTC Cadet Superior Cadet - JROTC Superior Cadet Decoration, is an U.S. military decoration awarded by DA and limited to one outstanding cadet in each LET level in each JROTC institution. To be considered eligible for this award, an individual must be: • A JROTC cadet.