The Pact of Geryon: an Italian Theory of Ethics and Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

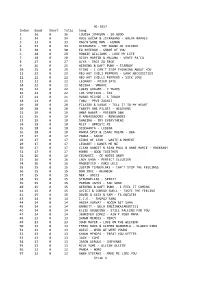

01-2017 Index Good Short Total Song 1 36 0 36 LOUISA JOHNSON

01-2017 Index Good Short Total Song 1 36 0 36 LOUISA JOHNSON - SO GOOD 2 34 0 34 RUDI BUČAR & ISTRABAND - GREVA NAPREJ 3 33 0 33 RAG'N'BONE MAN - HUMAN 4 33 0 33 DISTURBED - THE SOUND OF SILENCE 5 30 0 30 ED SHEERAN - SHAPE OF YOU 6 28 0 28 ROBBIE WILLIAMS - LOVE MY LIFE 7 28 0 28 RICKY MARTIN & MALUMA - VENTE PA'CA 8 27 0 27 ALYA - SRCE ZA SRCE 9 26 0 26 WEEKEND & DAFT PUNK - STARBOY 10 25 0 25 STING - I CAN'T STOP THINKING ABOUT YOU 11 23 0 23 RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS - DARK NECESSITIES 12 22 0 22 RED HOT CHILLI PEPPERS - SICK LOVE 13 22 0 22 LEONART - POJEM ZATE 14 22 0 22 NEISHA - VRHOVI 15 22 0 22 LUKAS GRAHAM - 7 YEARS 16 22 0 22 LOS VENTILOS - ČAS 17 21 0 21 RUSKO RICHIE - S TOBOM 18 21 0 21 TABU - PRVI ZADNJI 19 20 0 20 FILATOV & KARAS - TELL IT TO MY HEART 20 20 0 20 TWENTY ONE PILOTS - HEATHENS 21 19 0 19 OMAR NABER - POSEBEN DAN 22 19 0 19 X AMBASSADORS - RENEGADES 23 19 0 19 SHAKIRA - TRY EVERYTHING 24 18 0 18 NIET - OPROSTI MI 25 18 0 18 SIDDHARTA - LEDENA 26 18 0 18 MANCA ŠPIK & ISAAC PALMA - OBA 27 17 0 17 PANDA - SANJE 28 17 0 17 KINGS OF LEON - WASTE A MOMENT 29 17 0 17 LEONART - DANES ME NI 30 17 0 17 CLEAN BANDIT & SEAN PAUL & ANNE MARIE - ROCKBABY 31 17 0 17 HONNE - GOOD TOGETHER 32 16 0 16 ČEDAHUČI - ČE HOČEŠ GREM 33 16 0 16 LADY GAGA - PERFECT ILLUSION 34 16 0 16 MAGNIFICO - KUKU LELE 35 15 0 15 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE - CAN'T STOP THE FEELINGS 36 15 0 15 BON JOVI - REUNION 37 15 0 15 NEK - UNICI 38 15 0 15 STRUMBELLAS - SPIRIT 39 15 0 15 PARSON JAMES - SAD SONG 40 15 0 15 WEEKEND & DAFT PUNK - I FEEL IT COMING 41 15 0 15 AVIICI & CONRAD SWELL - TASTE THE FEELING 42 15 0 15 DAVID & ALEX & SAM - TA OBČUTEK 43 14 0 14 I.C.E. -

Part III Workshops & Competitions Entries

Part III Workshops & Competitions Entries recall – european conflict archaeological landscape reappropriation — 119 About REcall seeks to formulate a new role of the architectural environment based on invigorated research on the cultural landscapes of WWI and WWII, and to strengthen the attention on the management, documenta- tion and fruition of such a heritage. The project regards heritage as a dynamic process, involving the declara- tion of our memory of past events and actions that have been refashioned for present day purposes such as identity, community, legalisation of pow- er and authority. According to the project group, any cultural landscape or urbanscape is characterised by its dynamism, temporality and chang- ing priorities in social perception. We stress that the research we develop will generate the values to be pro- tected tomorrow. On the strength of this account, our project proposes the development of sustainable and innovative architectural practices for reuse, valorisation and communication of the XXth Century European Conflict Heritage. æ Project Description The project provides improved knowledge and advancement in the state of the art of Cultural Heritage diversity in Europe. By establishing syn- ergies between leading national and local institutions, the project brings together diverse theoretical, methodological, phenomenological and op- erative contributions on the interpretation of Conflict Heritage. Such synergies provide a framework to develop innovative research strategies based on the power of doing. Indeed, the main objective of our project is the reuse and reappropriation of difficult heritage through the reconcilia- tion of people and their memories. This operation will support European policies in Cultural Landscape Interpretation in relation to the citizen- ship formation processes of post-national societies. -

Young Howard the Making of a Male Lesbian a Novel by T.L. Winslow (C) Copyright 2000 by T.L. Winslow. All Rights Reserved. This

C:\younghoward\younghoward.txt Friday, June 07, 2013 2:30 PM Young Howard The Making Of A Male Lesbian A Novel by T.L. Winslow (C) Copyright 2000 by T.L. Winslow. All Rights Reserved. This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. -1- C:\younghoward\younghoward.txt Friday, June 07, 2013 2:30 PM PREFACE This is my secret autobiography of my childhood. I keep it in encrypted form on my personal computer where only I can get at it. My password is pAtTypUkE. I don't want it to be published or known while I'm alive, but kept only for my private masturbation fantasies. I will supply the password to it in my will, with instructions to my lawyer to release it fifty years after my death. In case anybody cracks it, beware of the curse of Tutankhamen and respect its privacy. In the extremely unlikely event that somebody does crack it and publish it, I'm warning you: at least have the human decency to obliterate my name and label it as fiction. I make millions a year and can hire detectives and sue your ass off can't I? Labelled as fiction about a fictional character, I have plausible deniability and so do you. Humor me, okay? Note from the Editor. This document was indeed hacked and then mutilated as it circulated furiously around the Howard fan sites on the Web, with many Billy Shakespeares making anonymous additions. -

Journal of Italian Translation

Journal of Italian Translation Journal of Italian Translation is an international journal devoted to the translation of literary works Editor from and into Italian-English-Italian dialects. All Luigi Bonaffini translations are published with the original text. It also publishes essays and reviews dealing with Italian Associate Editors translation. It is published twice a year. Gaetano Cipolla Michael Palma Submissions should be in electronic form. Trans- Joseph Perricone lations must be accompanied by the original texts Assistant Editor and brief profiles of the translator and the author. Paul D’Agostino Original texts and translations should be in separate files. All inquiries should be addressed to Journal of Editorial Board Italian Translation, Dept. of Modern Languages and Adria Bernardi Literatures, 2900 Bedford Ave. Brooklyn, NY 11210 Geoffrey Brock or [email protected] Franco Buffoni Barbara Carle Book reviews should be sent to Joseph Perricone, Peter Carravetta John Du Val Dept. of Modern Language and Literature, Fordham Anna Maria Farabbi University, Columbus Ave & 60th Street, New York, Rina Ferrarelli NY 10023 or [email protected] Luigi Fontanella Irene Marchegiani Website: www.jitonline.org Francesco Marroni Subscription rates: U.S. and Canada. Sebastiano Martelli Individuals $30.00 a year, $50 for 2 years. Adeodato Piazza Institutions $35.00 a year. Nicolai Single copies $18.00. Stephen Sartarelli Achille Serrao Cosma Siani For all mailing abroad please add $10 per issue. Marco Sonzogni Payments in U.S. dollars. Joseph Tusiani Make checks payable to Journal of Italian Trans- Lawrence Venuti lation Pasquale Verdicchio Journal of Italian Translation is grateful to the Paolo Valesio Sonia Raiziss Giop Charitable Foundation for its Justin Vitiello generous support. -

Cairoli Merda

Voci di Corridoio Numero 50—Anno III settimanale fraccarotto 15 novembre 2007 CAIROLI MERDA LA SOMIGLIANZA E CHI L’AVREBBE MAI DETTO? Abito al piano terra, per cui non devo più fare punto di Gotta’, mentre il dibattito sulle que- tutti quegli scalini. Oltretutto, è assai raro che stioni d’attualità si faceva sempre più serrato. LO SBERLEFFO un vicino di casa ostacoli il mio cammino Si poteva approfittare dei consigli eat&drink verso la porta di casa. Tutto è molto meno di Giuliano e Turconi, o perdersi nei racconti Quando si usa internet bisogna fare sempre faticoso. di De Barbieri. molta attenzione: non tanto a come lo si usa, Nascevano anche infausti appuntamenti, co- piuttosto a chi si ha a fianco quando lo si usa. E così, Voci di Corridoio è arrivato a quota 50. me ‘Il grande bordello’ o l’indimenticabile Maragliano è un ragazzo di cui bisogna stare Chi l’avrebbe mai detto? A partire da quel meteora ‘Sem Cumasch’, iniziative apprezzate attenti sempre (nel senso buono, s’intende!). in ogni caso dai E’ uno di quegli elementi disposti a tutto pur lettori più grosso- di spezzare la ripetitività dei giorni di novem- lani. bre. E se una sera manda qualche capellone a E, a proposito di iniziative, quelle recapitare un pacco “importante” nelle mani della redazione di Idro, può anche darsi che due giorni dopo si sono sempre state inventi una storiella ad hoc capace di cataliz- originali e diver- zare l’attenzione del collegio e non solo. Basta tenti, a partire dal una sbirciata alla rete, una somiglianza azzec- semplice ma irri- cata e comincia il divertimento. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2015

Jan 15 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) gathered in New York to celebrate the Great Detective's 161st birthday during the long weekend from Jan. 7 to Jan. 11. The festivities began with the traditional ASH Wednesday dinner sponsored by The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes at Annie Moore's, and continued with the Christopher Morley Walk led by Jim Cox and Dore Nash on Thursday morn- ing, followed by the usual lunch at McSorley's. The Baker Street Irregulars' Distinguished Speaker at the Midtown Executive Club on Thursday evening was Alan Bradley, co-author of MS. HOLMES OF BAKER STREET (2004), and author of the award-winning "Flavia de Luce" series; the title of his talk was "Ha! The Stars Are Out and the Wind Has Fallen" (his paper will be published in the next issue of The Baker Street Journal). The William Gillette Luncheon at Moran's Restaurant was well attended, as always, and the Friends of Bogie's at Baker Street (Paul Singleton and An- drew Joffe) entertained the audience with an updated version of "The Sher- lock Holmes Cable Network" (2000). The luncheon also was the occasion for Al Gregory's presentation of the annual Jan Whimsey Award (named in memory of his wife Jan Stauber), which honors the most whimsical piece in The Ser- pentine Muse last year: the winner (Jenn Eaker) received a certificate and a check for the Canonical sum of $221.17. And Otto Penzler's traditional open house at the Mysterious Bookshop provided the usual opportunities to browse and buy. -

See 2019 Festival Program for Review

Celebrating 10 years in the Media Capital of the World September 5th - 9th September 5, 2018 Dear Friends: On behalf of the City of Los Angeles, welcome to the 2018 Burbank International Film Festival. Since 2009, the Burbank International Film Festival has promoted up-and-coming filmmakers from around the world by providing a gateway to expand their careers in the entertainment industry. I applaud the efforts of the Festival’s organizers and sponsors to create an event that generates an appreciation of storytelling through film. Thank you for your contributions to the vibrant artistic culture of Los Angeles. Congratulations to all the Industry Icon honorees. I send my best wishes for what is sure to be a successful and memorable event. Sincerely, ERIC GARCETTI Mayor September 5, 2018 Dear Friends, Welcome to the 2018 Burbank International Film Festival as we celebrate 10 successful years in "The Media Capitol of the World." The Burbank International Film Festival has given a platform to promising filmmakers, sharing their hard work with an eager audience and providing the means to expand their budding careers. As champions of independent filmmaking, the Festival organizers represent true benefactors to the colorful Los Angeles arts scene that we all enjoy. Congratulations to all the Festival honorees at this pivotal point in their careers. We appreciate your dedication and the contribution it makes to our arts culture. Sincerely, ANTHONY J. PORTANTINO Senator 25th Senate District Board of Directors Jeff Rector President / Festival Director Jeff is an award-winning filmmaker and working actor. His feature film “Revamped” which he wrote, directed and produced, is currently being distributed worldwide. -

The Daily Egyptian, December 05, 1994

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC December 1994 Daily Egyptian 1994 12-5-1994 The aiD ly Egyptian, December 05, 1994 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_December1994 Volume 80, Issue 68 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1994 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in December 1994 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DailyEgxJJlil!J.n Southern Illinois University at Carbondale .:' ~-~~~:;;;~:Monday, ~~ber 5, 1994, Vol. 80, No. 68, 16 Pages Clinton, GOP Historic Carbondale- e_i(~lotc:J leaders clash Tour showcases over Bosnia Los Angeles Times old homes, carols WASHINGTON-The Clinton By Dean Weaver administration clashed sharply with Senior Reporter top GOP lawmakers Sunday over U.S. policy in Bosnia. as the The Old Carhondak Sparkks Tour on Republicans called for the with Sunday provided participants with holiday drawal of U.N. peacekeepers and d1ecr.sm11bined with the flavor ofyesteryq,.,, the bombing of the Serbian nation Thci (our. sponsored by the Carbondale I I alists and key Cabinet members Convention and Tourism Bureau. gave countered that such moves would Carbondale residents and tourists a chance to mean a wider war. S<.'C historic Carhondale homes decorated with In a day of cross-fire on the garlands and lights. and 10 hear carols sung by Sunday television talk shows. a local church choir. incoming Senate Majority Leader Debbie Moore. director of the Carbondale Bob Dole. R-Kan .. and House Convention and Tourism Bureau. -

FARM for SALE: FARM for SALE: 000 Maple Hill RD

Manhattan Commission Company -13 Grass & Grain, October 16, 2018 Page 13 Sow lifetime productivity provides a more complete picture It’s time to rethink sow from the time she becomes fore exiting the farrowing This year, the Nation- productivity measures breeding eligible until she stall. al Pork Board expanded Sow lifetime produc- leaves the herd. But too “We need to look at its sow longevity efforts tivity (SLP) is defined as many sows leave the herd sow data differently,” said by organizing the Pig Sur- the total number of qual- too soon. Research shows Chris Hostetler, animal vivability Working Group. ity pigs that a sow weans that one in 40 sows die be- science director for Pork The Pork Checkoff’s ani- Checkoff. “Pigs per sow mal science committee has per year not only fails to committed nearly 80 per- address the sow’s longevi- cent of its 2018 research KB Classen 4517 won reserve supreme champion ty; it does not account for budget to the effort, with piglet quality or viability.” the animal welfare and overall breeds and grand champion owned female In 2010, the National swine health committees at the 2018 Kansas State Fair Junior Angus Show, Pork Board’s producer-led bringing total Checkoff Sept. 9 in Hutchinson. Ashley Kennedy, Satanta, committees created the funding to $1 million. Iowa owns the March 2017 daughter of EXAR Classen Sow Lifetime Productivi- State University research- 1422B. ty Task Force to identify ers, headed by Jason Ross, and fund research to ad- Iowa Pork Industry Center dress areas that affect SLP. -

The PACT of Patient Engagement: Unraveling the Meaning Of

The PACT of Patient Engagement: Unraveling the Meaning of Engagement with Hybrid Concept Analysis Tracy Higgins Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Tracy Higgins All rights reserved ABSTRACT The PACT of Patient Engagement: Unraveling the Meaning of Engagement with Hybrid Concept Analysis Tracy Higgins Patient engagement has become a widely used term, but remains a poorly understood concept in healthcare. Citations for the term during the past two decades have increased markedly throughout the healthcare-related disciplines without a common definition. Patient engagement has been credited for contributing to improved outcomes and experiences of care. Means of identifying and evaluating practices that facilitate patient engagement in care have become an ethical imperative for patient-centered care. This process begins with a definition of the concept. Concept analysis is a means of establishing a common definition of a concept through identification of its attributes, antecedents and consequences within the context of its use. Concept analysis is a methodology that has been used in social science and nursing as a means to resolve conceptual barriers to theory development in an evolving field. The methodological theory was based in the analytic philosophical tradition and sustained during the 20th century by the strength of philosophical positivism in the health sciences. This concept analysis is guided procedurally by Rogers’ evolutionary approach that incorporates postmodern philosophical principles and well-defined techniques. This dissertation is informed by the expanded and updated perspective of the neo-modern era in nursing research, which advances the concept analysis methodology further. -

Did Pope Pius XII Help the Jews?

Did Pope Pius XII Help the Jews? by Margherita Marchione 1 Contents Part I - Overview………………………3 Did Pius XII help Jews? Part II - Yad Vashem …………………6 Does Pius XII deserve this honor? Part III - Testimonials…………………11 Is Jewish testimony available? Part IV - Four Hundred Visas……….16 Did Pius XII obtain these visas? Part V - Documentation………………19 When will vilification of Pius XII end? Part VI - World Press………………...23 How has the press responded? Part VII - Jewish Survivors…………...31 Have Survivors acknowledged help? Part VIII - Bombing of Rome…………34 Did the Pope help stop bombing? Part IX - Nazis and Jews Speak Out…37 Did Nazis and Jews speak out? Part X - Conclusion…………………....42 Should Yad Vashem honor Pius XII? 2 Part I - Overview Did Pius XII help Jews? In his book Adolf Hitler (Doubleday, 1976, Volume II, p. 865), John Toland wrote: "The Church, under the Pope's guidance [Pius XII], had (by June, 1943) already saved the lives of more Jews than all other churches, religious institutions and rescue organizations combined, and was presently hiding thousands of Jews in monasteries, convents and Vatican City itself. …The British and Americans, despite lofty pronouncements, had not only avoided taking any meaningful action but gave sanctuary to few persecuted Jews." It is historically correct to say that Pope Pius XII, through his bishops, nuncios, and local priests, mobilized Catholics to assist Jews, Allied soldiers, and prisoners of war. There is a considerable body of scholarly opinion that is convinced Pius XII is responsible for having saved 500,000 to 800,000 Jewish lives. -

Celebrating 50Years of the Prisoner

THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION www.infinitymagazine.co.uk THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION 6 DOUBLE-SIDED POSTER INSIDE! “I AM NOT A NUMBER!” CELEBRATING 50 YEARS PLUS: OF THE PRISONER • CHRISTY MARIE - COSPLAY QUEEN • SPACECRAFT KITS • IAIN M. BANKS • THE VALLEY OF GWANGI • NEWS • SATURDAY MORNING SUPERHEROES • CHILDREN’S FILM FOUNDATION AND MUCH, MUCH MORE… FUTURE SHOCK! THE HISTORY OF 2000 AD AN ARRESTING CONCEPT - TAKE A TRIP IN ROBOCOP THE TIME TUNNEL WRITER INFINITY ISSUE 6 - £3.99 06 THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION www.infinitymagazine.co.uk 6 THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION DOUBLE-SIDED POSTER INSIDE! 8 14 “I AM NOT A 38 NUMBER!”50 YEARS CELEBRATING OF THE PRISONER • SPACECRAFT KITS PLUS: • NEWS • CHRISTY MARIE• THE - COSPLAY VALLEY QUEEN OF GWANGI• CHILDREN’S • IAIN M. BANKS • SATURDAY MORNING SUPERHEROES FILM FOUNDATION AND MUCH, MUCH MORE… FUTURE SHOCK! AN ARRESTING THE HISTORY OF CONCEPT - 2000 AD ROBOCOP WRITER TAKE A TRIP IN THE TIME TUNNEL INFINITY ISSUE 6 - £3.99 Prisoner cover art by Mark Maddox (www.maddoxplanet.com) 19 44 08: CONFESSIONS OF A CONVENTION QUEEN Pat Jankiewicz discovers how Star Wars FanGirl Christy Marie became a media phenomenon! 14: SATURDAY MORNING SUPER-HEROES Jon Abbott looks at Hanna-Barbera’s Super TV Heroes line of animated adventurers. 19: UNLOCKING THE PRISONER Don’t miss this amazing 11-page special feature on Patrick McGoohan’s cult favourite from the 1960s. 38: MODEL BEHAVIOUR Sci-fi & Fantasy Modeller’s Andy Pearson indulges his weakness for spacecraft kits… 40 40: FUTURE SHOCK! John Martin talks to Paul Goodwin, director of an acclaimed documentary on the history of 2000 AD.