Lectward M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documenting the University of Pennsylvania's Connection to Slavery

Documenting the University of Pennsylvania’s Connection to Slavery Clay Scott Graubard The University of Pennsylvania, Class of 2019 April 19, 2018 © 2018 CLAY SCOTT GRAUBARD ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 2 OVERVIEW 3 LABOR AND CONSTRUCTION 4 PRIMER ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLLEGE AND ACADEMY OF PHILADELPHIA 5 EBENEZER KINNERSLEY (1711 – 1778) 7 ROBERT SMITH (1722 – 1777) 9 THOMAS LEECH (1685 – 1762) 11 BENJAMIN LOXLEY (1720 – 1801) 13 JOHN COATS (FL. 1719) 13 OTHERS 13 LABOR AND CONSTRUCTION CONCLUSION 15 FINANCIAL ASPECTS 17 WEST INDIES FUNDRAISING 18 SOUTH CAROLINA FUNDRAISING 25 TRUSTEES OF THE COLLEGE AND ACADEMY OF PHILADELPHIA 31 WILLIAM ALLEN (1704 – 1780) AND JOSEPH TURNER (1701 – 1783): FOUNDERS AND TRUSTEES 31 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN (1706 – 1790): FOUNDER, PRESIDENT, AND TRUSTEE 32 EDWARD SHIPPEN (1729 – 1806): TREASURER OF THE TRUSTEES AND TRUSTEE 33 BENJAMIN CHEW SR. (1722 – 1810): TRUSTEE 34 WILLIAM SHIPPEN (1712 – 1801): FOUNDER AND TRUSTEE 35 JAMES TILGHMAN (1716 – 1793): TRUSTEE 35 NOTE REGARDING THE TRUSTEES 36 FINANCIAL ASPECTS CONCLUSION 37 CONCLUSION 39 THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 40 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 42 BIBLIOGRAPHY 43 DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 2 INTRODUCTION DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 3 Overview The goal of this paper is to present the facts regarding the University of Pennsylvania’s (then the College and Academy of Philadelphia) significant connections to slavery and the slave trade. The first section of the paper will cover the construction and operation of the College and Academy in the early years. As slavery was integral to the economy of British North America, to fully understand the University’s connection to slavery the second section will cover the financial aspects of the College and Academy, its Trustees, and its fundraising. -

Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: an Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1992 Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991) Frederick Lee Richards University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Richards, Frederick Lee, "Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991)" (1992). Theses (Historic Preservation). 349. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/349 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Richards, Frederick Lee (1992). Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991). (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/349 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991) Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Richards, Frederick Lee (1992). Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: -

Philadelphia, the Indispensable City of the American Founding the FPRI Ginsburg—Satell Lecture 2020 Colonial Philadelphia

Philadelphia, the Indispensable City of the American Founding The FPRI Ginsburg—Satell Lecture 2020 Colonial Philadelphia Though its population was only 35,000 to 40,000 around 1776 Philadelphia was the largest city in North America and the second-largest English- speaking city in the world! Its harbor and central location made it a natural crossroads for the 13 British colonies. Its population was also unusually diverse, since the original Quaker colonists had become a dwindling minority among other English, Scottish, and Welsh inhabitants, a large admixture of Germans, plus French Huguenots, Dutchmen, and Sephardic Jews. But Beware of Prolepsis! Despite the city’s key position its centrality to the American Revolution was by no means inevitable. For that matter, American independence itself was by no means inevitable. For instance, William Penn (above) and Benjamin Franklin (below) were both ardent imperial patriots. We learned of Franklin’s loyalty to King George III last time…. Benjamin Franklin … … and the Crisis of the British Empire The FPRI Ginsburg-Satell Lecture 2019 The First Continental Congress met at Carpenters Hall in Philadelphia where representatives of 12 of the colonies met to protest Parliament’s Coercive Acts, deemed “Intolerable” by Americans. But Congress (narrowly) rejected the Galloway Plan under which Americans would form their own legislature and tax themselves on behalf of the British crown. Hence, “no taxation without representation” wasn’t really the issue. WHAT IF… The Redcoats had won the Battle of Bunker Hill (left)? The Continental Army had not escaped capture on Long Island (right)? Washington had been shot at the Battle of Brandywine (left)? Or dared not undertake the risky Yorktown campaign (right)? Why did King Charles II grant William Penn a charter for a New World colony nearly as large as England itself? Nobody knows, but his intention was to found a Quaker colony dedicated to peace, religious toleration, and prosperity. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

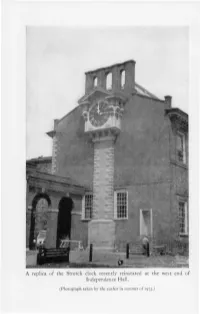

A Replica of the Stretch Clock Recently Reinstated at the West End of Independence Hall

A replica of the Stretch clock recently reinstated at the west end of Independence Hall. (Photograph taken by the author in summer of 197J.) THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Stretch Qlock and its "Bell at the State House URING the spring of 1973, workmen completed the construc- tion of a replica of a large clock dial and masonry clock D case at the west end of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the original of which had been installed there in 1753 by a local clockmaker, Thomas Stretch. That equipment, which resembled a giant grandfather's clock, had been removed in about 1830, with no other subsequent effort having been made to reconstruct it. It therefore seems an opportune time to assemble the scattered in- formation regarding the history of that clock and its bell and to present their stories. The acquisition of the original clock and bell by the Pennsylvania colonial Assembly is closely related to the acquisition of the Liberty Bell. Because of this, most historians have tended to focus their writings on that more famous bell, and to pay but little attention to the hard-working, more durable, and equally large clock bell. They have also had a tendency either to claim or imply that the Liberty Bell and the clock bell had been procured in connection with a plan to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary, or "Jubilee Year," of the granting of the Charter of Privileges to the colony by William Penn. But, with one exception, nothing has been found among the surviving records which would support such a contention. -

Chapter 5 the Americans.Pdf

Washington (on the far right) addressing the Constitutional Congress 1785 New York state outlaws slavery. 1784 Russians found 1785 The Treaty 1781 The Articles of 1783 The Treaty of colony in Alaska. of Hopewell Confederation, which Paris at the end of concerning John Dickinson helped the Revolutionary War 1784 Spain closes the Native American write five years earli- recognizes United Mississippi River to lands er, go into effect. States independence. American commerce. is signed. USA 1782 1784 WORLD 1782 1784 1781 Joseph II 1782 Rama I 1783 Russia annexes 1785 Jean-Pierre allows religious founds a new the Crimean Peninsula. Blanchard and toleration in Austria. dynasty in Siam, John Jeffries with Bangkok 1783 Ludwig van cross the English as the capital. Beethoven’s first works Channel in a are published. balloon. 130 CHAPTER 5 INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1787. You have recently helped your fellow patriots overthrow decades of oppressive British rule. However, it is easier to destroy an old system of government than to create a new one. In a world of kings and tyrants, your new republic struggles to find its place. How much power should the national government have? Examine the Issues • Which should have more power—the states or the national government? • How can the new nation avoid a return to tyranny? • How can the rights of all people be protected? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 5 links for more information about Shaping a New Nation. 1786 Daniel Shays leads a rebellion of farmers in Massachusetts. 1786 The Annapolis Convention is held. -

1 the Story of the Faulkner Murals by Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. the Story Of

The Story of the Faulkner Murals By Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. The story of the Faulkner murals in the Rotunda begins on October 23, 1933. On this date, the chief architect of the National Archives, John Russell Pope, recommended the approval of a two- year competing United States Government contract to hire a noted American muralist, Barry Faulkner, to paint a mural for the Exhibit Hall in the planned National Archives Building.1 The recommendation initiated a three-year project that produced two murals, now viewed and admired by more than a million people annually who make the pilgrimage to the National Archives in Washington, DC, to view two of the Charters of Freedom documents they commemorate: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America. The two-year contract provided $36,000 in costs plus $6,000 for incidental expenses.* The contract ended one year before the projected date for completion of the Archives Building’s construction, providing Faulkner with an additional year to complete the project. The contract’s only guidance of an artistic nature specified that “The work shall be in character with and appropriate to the particular design of this building.” Pope served as the contract supervisor. Louis Simon, the supervising architect for the Treasury Department, was brought in as the government representative. All work on the murals needed approval by both architects. Also, The United States Commission of Fine Arts served in an advisory capacity to the project and provided input critical to the final composition. The contract team had expertise in art, architecture, painting, and sculpture. -

Joseph Saxton

MEMOIR OP JOSEPH SAXTON. 1799-1873. BY JOSEPH HENRY. HEAD BEFOEB THB NATIONAL ACADEMY, OCT. 4,1874. 28T BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JOSEPH SAXTON. MR. PRESIDENT AND GENTLEMEN OF THE ACADEMY :— AT the last session of the National Academy of Sciences I was appointed to prepare an account of the life and labors of our lamented associate, Joseph Saxton, whose death we have been called to mourn. From long acquaintance and friendly relations with the deceased, the discharge of the duty thus devolved upon me has been a labor of love, but had he been personally unknown to me, the preparation of the eulogy would have been none the less a sacred duty, which I was not at liberty on any account to neglect. It is an obligation we owe to the Academy and the world to cherish the memory of our departed associates; their reputation is a precious inheritance to the Academy which exalts its character and extends its usefulness. Man is a sympathetic and imitative being, and through these characteristics of his nature the memories of good men produce an important influence on posterity, and therefore should be cherished and perpetuated. Moreover, the certainty of having a just tribute paid to our memory after our departure is one of the most powerful inducements to purity of life and propriety of deportment. The object of the National Academy is the advancement of science, and no one is considered eligible for membership who has not made positive additions to the sum of human knowledge, or in other words, has not done something to entitle him to the appellation of scientific. -

Chapter 2: Above the Roof: Exquisite Miniature

Above the Roof 35 Figure 1 18th Century Engraving of Philadelphia Skyline, Nicholas Scull engraver Chapter 2: Above the Roof: Exquisite Miniature The late Alfred Kazin, one of New York’s intelligentsia, mused as he looked out the window toward the city, “I feel I am dreaming aloud as I look at the rooftops, at the sky, at the massed white skyline of New York. The view across the rooftops is as charged as the indented black words on the white page. The mass and pressure of the bulging skyline are wild.”1 As ships at sea, as inscriptions on a page, yet full as the body of an animal, wild, the city skyline revealed the “beautiful bedlam and chaos of New York” in a profile that flattens the mass of buildings into a cipher. The same buildings when seen from below and close at hand, thicken into squat forms distorted by foreshortening. Vitruvius acknowledged the mutability of scale in the design of upper story columns or sculpture, recommending that they be elongated proportionally so they would not appear to be pitching forward.2 He also advised reducing the upper tier of military towers by one fifth so they would not seem top-heavy when seen from below. The smaller and taller proportions of aerial architecture take into account the position of a viewer, addressing the eye more than the body. Alberti towers are excellent ornament In the 15th century, Leon Battista Alberti wrote that watchtowers were “an excellent ornament” for the profile of a building. He proposed exaggerating the apparent height through a proportional reduction in the size of each successive tier of a tower. -

National Historical Park Pennsylvania

INDEPENDENCE National Historical Park Pennsylvania Hall was begun in the spring of 1732, when from this third casting is the one you see In May 1775, the Second Continental Con The Constitutional Convention, 1787 where Federal Hall National Memorial now ground was broken. today.) gress met in the Pennsylvania State House stands. Then, in 1790, it came to Philadel Edmund Woolley, master carpenter, and As the official bell of the Pennsylvania (Independence Hall) and decided to move The Articles of Confederation and Perpet phia for 10 years. Congress sat in the new INDEPENDENCE ual Union were drafted while the war was in Andrew Hamilton, lawyer, planned the State House, the Liberty Bell was intended to from protest to resistance. Warfare between County Court House (now known as Con building and supervised its construction. It be rung on public occasions. During the the colonists and British troops already had progress. They were agreed to by the last of gress Hall) and the United States Supreme NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK was designed in the dignity of the Georgian Revolution, when the British Army occupied begun in Massachusetts. In June the Con the Thirteen States and went into effect in Court in the new City Hall. In Congress period. Independence Hall, with its wings, Philadelphia in 1777, the bell was removed gress chose George Washington to be Gen the final year of the war. Under the Arti Hall, George Washington was inaugurated has long been considered one of the most to Allentown, where it was hidden for almost eral and Commander in Chief of the Army, cles, the Congress met in various towns, only for his second term as President. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

Form No. ^0-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Independence National Historical Park AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 313 Walnut Street CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT t Philadelphia __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE PA 19106 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM -BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —^COMMERCIAL 2LPARK .STRUCTURE 2EBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —XEDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED ^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: REGIONAL HEADQUABIER REGION STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE PHILA.,PA 19106 VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, ____________PhiladelphiaREGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. _, . - , - , Ctffv.^ Hall- - STREET & NUMBER n^ MayTftat" CITY. TOWN STATE Philadelphia, PA 19107 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL CITY. TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2S.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD h^b Jk* SANWJIt's ALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Description: In June 1948, with passage of Public Law 795, Independence National Historical Park was established to preserve certain historic resources "of outstanding national significance associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States." The Park's 39.53 acres of urban property lie in Philadelphia, the fourth largest city in the country. All but .73 acres of the park lie in downtown Phila-* delphia, within or near the Society Hill and Old City Historic Districts (National Register entries as of June 23, 1971, and May 5, 1972, respectively). -

George Washington's Farewell Address My Account | Register | Help

George Washington's farewell address My Account | Register | Help My Dashboard Get Published Home Books Search Support About Get Published Us Most Popular New Releases Top Picks eBook Finder... SEARCH G E O R G E W A S H I N G T O N ' S F A R E W E L L A D D R E S S Article Id: WHEBN0001291578 Reproduction Date: Title: George Washington's Farewell Address Author: World Heritage Encyclopedia Language: English Subject: Collection: Publisher: World Heritage Encyclopedia Publication Date: Flag as Inappropriate Email this Article GEORGE WASHINGTON'S FAREWELL ADDRESS George Washington's Farewell Address is a letter written by the first American [1] Washington wrote the This article is part of a series about letter near the end of his second term as President, before his retirement to his home Mount Vernon. George Washington Originally published in Daved Claypole's American Daily Advertiser on September 19, 1796, under the title "The Address of General Washington To The People of The United States on his declining of the Presidency of the United States," the letter was almost immediately reprinted in newspapers across the country and later in a pamphlet form.[2] The work was later named a "Farewell Address," as it was Washington's valedictory after 20 years of service to the new nation. It is a classic statement of republicanism, warning Americans of the political dangers they can and must avoid if they are to remain true to their values. The first draft was originally prepared in 1792 with the assistance of James Madison,[3] as Washington prepared to retire following a single term in office.