Serbian Orthodox Church in the Context of State's History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference List

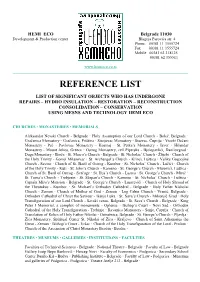

HEMI ECO Belgrade 11030 Development & Production center Blagoja Parovića str. 4 Phone 00381 11 3555724 Fax 00381 11 3555724 Mobile 00381 63 318125 00381 62 355511 www.hemieco.co.rs _______________________________________________________________________________________ REFERENCE LIST LIST OF SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS WHO HAS UNDERGONE REPAIRS – HYDRO INSULATION – RESTORATION – RECONSTRUCTION CONSOLIDATION – CONSERVATION USING MESNS AND TECHNOLOGY HEMI ECO CHURCHES • MONASTERIES • MEMORIALS Aleksandar Nevski Church - Belgrade · Holy Assumption of our Lord Church - Boleč, Belgrade · Gračanica Monastery - Gračanica, Priština · Sisojevac Monastery - Sisevac, Ćuprija · Visoki Dečani Monastery - Peć · Pavlovac Monastery - Kosmaj · St. Petka’s Monastery - Izvor · Hilandar Monastery - Mount Athos, Greece · Ostrog Monastery, cell Piperska - Bjelopavlići, Danilovgrad · Duga Monastery - Bioča · St. Marco’s Church - Belgrade · St. Nicholas’ Church - Žlijebi · Church of the Holy Trinity - Gornji Milanovac · St. Archangel’s Church - Klinci, Luštica · Velike Gospojine Church - Savine · Church of St. Basil of Ostrog - Kumbor · St. Nicholas’ Church - Lučići · Church of the Holy Trinity - Kuti · St. John’s Church - Kameno · St. George’s Church - Marovići, Luštica · Church of St. Basil of Ostrog - Svrčuge · St. Ilija’s Church - Lastva · St. George’s Church - Mirač · St. Toma’s Church - Trebjesin · St. Šćepan’s Church - Kameno · St. Nicholas’ Church - Luštica · Captain Miša’s Mansion - Belgrade · St. George’s Church - Lazarevići · Church of Holy Shroud of the Theotokos -

Akathist to Saint Sava First Archbishop of Serbia

Akathist to Saint Sava First Archbishop of Serbia Kontakion 1 Chosen by the King of All Power, Lord Jesus Christ, and called by grace from royal lineage into monasticism and archbishoprics, first saint of the Serbian Church, God bearing Father Savo, allow us to praise you with love, God given shepherd and teacher. And you, who has freedom before the Lord, ceaselessly pray with your Father and Brother according to the flesh, Simeon the Myhrrgusher and Venerable Simon, for the salvation of your descendants, the Serbian Orthodox people, and for us sinners, redeeming us from all evil, troubles and sorrows. We exclaim to you: Rejoice St Savo First Serbian teacher and wonderful miracle worker! Ikos l Falling in love from your youth in angelic purity, blessed Savo, you showed yourself as a great ascetic of piety, thus that all wondered to the honesty and piety of your soul, but you as a lad and prince by birth tamed your flesh with fasting, vigil, and prayers. For this, hear our praising songs: Rejoice you, who is loved by God, son of a pious father and a good‐hearted mother. Rejoice you, who with all your heart fell in love with God. Rejoice you, who with your birth consoled your parents and solved their barrenness. Rejoice you, blessed fruit obtained by many prayers. Rejoice you, offspring of the royal lineage of Nemanja. Rejoice spiritual beauty of Serbian land. Rejoice comfort and joy of your parents in their old age. Rejoice you, whom they loved more than other children. Rejoice you, who rejected pleasures of the flesh even in your youth. -

Type: Charming Village Culture Historic Monuments Scenic Drive

Type: Charming Village Culture Historic Monuments Scenic Drive See the best parts of Montenegro on this mini tour! We take you to visit three places with a great history - three places with a soul. This is tour where you will learn about the old customs in Montenegro, and also those who maintain till today. See the incredible landscapes and old buildings that will not leave you indifferent. Type: Charming Village, Culture, Historic Monuments, Scenic Drive Length: 6 Hours Walking: Medium Mobility: No wheelchairs Guide: Licensed Guide Language: English, Italian, French, German, Russian (other languages upon request) Every Montenegrin will say: "Who didn't saw Cetinje, haven't been in Montenegro!" So don't miss to visit the most significant city in the history and culture of Montenegro and it's numerous monuments: The Cetinje monastery, from which Montenegrin bishops ruled through the centuries; Palace of King Nikola, Montenegrin king who together with his daughters made connection with 4 European courts; Vladin Dom, art museum with huge collection of art paintings and historical symbols, numerous embassies and museums... After meeting your guide at the pier, you walk to your awaiting vehicle which will take you to Njegusi, a quiet mountain village. Njegusi Njegusi is a village located on the slopes of mount Lovcen. This village is best known as birthplace of Montenegro's royal dynasty of Petrovic, which ruled Montenegro from 1696 to 1918. Njegusi is a birthplace of famous Montenegrin bishop and writer – Petar II Petrovic Njegos. The village is also significant for its well- preserved traditional folk architecture. Cheese and smoked ham (prosciutto) from Njegusi are made solely in area around Njegusi, are genuine contributions to Montenegrin cuisine. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy o f the original document. While the most advai peed technological meant to photograph and reproduce this document have been useJ the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The followini explanation o f techniques is provided to help you understand markings or pattei“ims which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target" for pages apparently lacking from die document phoiographed is “Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This| may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Wheji an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is ar indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have mo1vad during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. Wheh a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in 'sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to righj in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until com alete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, ho we ver, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "ph btographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich. Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich

Photo courtesy Alaska State Library, Michael Z. Vinokouroff Collection P243-1-082. Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich. Sebastian Archimandrite Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich. Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich SERBIAN ORTHODOX APOSTLE TO AMERICA by Hieromonk Damascene . A A U S during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, Archimandrite B Sebastian Dabovich has the distinction of being the first person born in the United States of America to be ordained as an Orthodox priest, 1 and also the first native-born American to be tonsured as an Orthodox monk. His greatest distinction, however, lies in the tremen- dous apostolic, pastoral, and literary work that he accomplished dur- ing the forty-eight years of his priestly ministry. Known as the “Father of Serbian Orthodoxy in America,” 2 he was responsible for the found- ing of the first Serbian churches in the New World. This, however, was only one part of his life’s work, for he tirelessly and zealously sought to spread the Orthodox Faith to all peoples, wherever he was called. He was an Orthodox apostle of universal significance. Describing the vast scope of Fr. Sebastian’s missionary activity, Bishop Irinej (Dobrijevic) of Australia and New Zealand has written: 1 Alaskan-born priests were ordained before Fr. Sebastian, but this was when Alaska was still part of Russia. 2 Mirko Dobrijevic (later Irinej, Bishop of Australia and New Zealand), “The First American Serbian Apostle—Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich,” Again, vol. 16, no. 4 (December 1993), pp. 13–14. THE ORTHODOX WORD “Without any outside funding or organizational support, he carried the gospel of peace from country to country…. -

Smilja Marjanović-Dušanić, L'écriture Et La Sainteté Dans La Serbie

Cahiers de civilisation médiévale Xe-XIIe siècle 240 bis | 2017 Hors-série 2 Smilja MARJANOVIĆ-DUŠANIĆ, L’écriture et la sainteté dans la Serbie médiévale : étude d’hagiographie Marie-Céline Isaïa Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ccm/5533 DOI : 10.4000/ccm.5533 ISSN : 2119-1026 Éditeur Centre d'études supérieures de civilisation médiévale Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 décembre 2017 Pagination : 509-511 ISBN : 978-2-490783-02-1 ISSN : 0007-9731 Référence électronique Marie-Céline Isaïa, « Smilja MARJANOVIĆ-DUŠANIĆ, L’écriture et la sainteté dans la Serbie médiévale : étude d’hagiographie », Cahiers de civilisation médiévale [En ligne], 240 bis | 2017, mis en ligne le 01 décembre 2019, consulté le 19 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ccm/5533 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/ccm.5533 La revue Cahiers de civilisation médiévale est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 741190090_INT_CCM 240 bis.pdf - Novembre 27, 2019 - 16:27:55 - 63 sur 112 - 210 x 270 mm - BAT DILA ALFONSO MARINI (éd.) 509 Smilja Marjanović-Dušanić, L’écriture et la sainteté sa mort ; son≈fils saint Sava doit à l’excellence de dans la Serbie médiévale : étude d’hagiographie, ses relations avec Constantinople le privilège de Turnhout, Brepols (Bibliothèque de l’École des relever le monastère de Chilandar sur l’Athos selon hautes études. Sciences religieuses, 179), 2017. ses deux Vies ; de l’autre côté du spectre chrono- logique, Constantin le Philosophe ou de Kostenec, Smilja Marjanović-Dušanić a donné avec Свети formé dans le monastère bulgare de Bačkovo, donne Краљ. -

Danilo Radojević

ideologija MISTIFIKACIJE I ASIMILATORSKI SMISAO IDEOLOGIJE SVETOSAVLJA Danilo Radojević Critical historiography has come to some important answers concerning the essence of the Serbian church-national ideology of svetosavlje and the manner of its spreading. Using old and making up new forgeries, some authors from the circle of the Serbian Orthodox Church are continuing to create a false image of this ideology. This text deals with researching propaganda methods of the so called svetosavlje. U novije vrijeme kritička istoriografija došla je do bitnijih odgo - vora, kada je u pitanju suština srpske crkveno-državne ideologije svetosavlja i način njenoga širenja, što neke autore iz kruga Srpske pravoslavne crkve sili da, koristeći stare i smišljajući nove falsifi - kate, stvaraju lažnu sliku i negiraju razarajuće rezultate asimila - torskoga pohoda ove ideologije na kulturno-povijesni i duhovni identitet jednoga dijela balkanskih naroda. Proučavanjem metoda propagande tzv. svetosavlja otkrivaju se glavni ciljevi te ideologi - je i dolazi do saznanja o korijenima i uzrocima razvoja animozite - ta kod jednog dijela Crnogoraca prema inovjercima. Ideologija svetosavlja , nastala prije više od stoljeća i po, a izme - đu dva svjetska rata, iz srpskoga crkvenoga vrha proklamovana u www. maticacrnogorska.me MATICA, ljeto 2012. 153 Danilo Radojević obliku političkoga modela imperijalnoga etnofiletizma, 1 oslonje - noga na lik jednoga nacionalnoga sveca, kamuflažno je zadržava - na u okvirima hrišćanske dogme, da bi trajnije i jače djelovala. Ta ideologija postala je oprobano sredstvo asimilatorskoga plavljenja svijesti kod pravoslavnijih dijelova (Srbima okolnih) naroda koji su se, poslije Prvoga svjetskoga rata, našli u granicama Kraljevine SHS. 2 Po svojem karakteru svetosavlje se naslanja na ideju o „iza - branom narodu“ što ga svrstava među ideologije rasizma. -

Political Rights of the Serbs in the Region 2018 REPORT SUMMARY

Political rights of the Serbs in the region 2018 REPORT SUMMARY Belgrade, 2018. POLITICAL RIGHTS OF THE SERBS IN THE REGION 2018 REPORT SUMMARY Publisher NGO Progresive club Zahumska 23B/86, 11 000 Belgrade, Serbia www.napredniklub.org, [email protected] For publisher Čedomir Antić Editor Čedomir Antić Written by Čedomir Antić Milan Dinić Ivana Leščen Miloš Vulević Vladimir Stanisavljev Aleksa Negić Branislav Tođer Aleksandar Ćurić Branko Okiljević Igor Vuković Translated by Miljana Protić Editorial board Miljan Premović Print and graphic design Pavle Halupa Jovana Vuković Printed by Shprint ISSN 1821-200X Print in: 1000 copies Progressive club POLITICAL RIGHTS OF THE SERBS IN THE REGION 2018 REPORT SUMMARY (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Republic of Croatia, Montenegro, Republic of Macedonia (FYRM), Albania, Republic Slovenia, Hungary, Romania, Kosovo and Metohija – Kosovo - UNMIK) Report for 2017/2018. No. 10 Belgrade, 2018. CONTENTS: Introduction . 7 Republic of Albania . 18 Bosnia and Hezegovina – The Republic of Srpska . 32 Republic of Croatia . .65 Hungary . .97 Kosovo and Metohija – Kosovo-UNMIK . 109 Republic of Macedonia (Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia) . 119 Montenegro . 153 Romania . 171 Republic of Slovenia . 181 Conclusion . 190 6 INTRODUCTION The Progressive Club, a Belgrade-based civil society organization, has been publishing reports on the political rights of the Serbian people in the region since 2009. This is its tenth annual report. Serbs are the largest nation based and concentrated in the territory of the Balkans, a large peninsula in Southeast Europe. The Balkans is the only European peninsula where geographic and historical reasons have always precluded the creation of a unified and functional modern state gov- erned by the domicile population. -

Proceedings Template

2020-4020-AJHIS 1 Serbian Royal Right to the Throne of Hungary at the Basis of the 2 Formation of Medieval Romanian Orthodox States 3 4 This paper shows that the overall situation in the Pannonian-Balkan area led 5 to the facts in the 14th -16th centuries on the background of which the 6 Romanian medieval states were formed and consolidated. The origins of 7 these facts derive from the interactions between the first Hungarian tribes 8 who came to the Pannonian area and the situation encountered here, which 9 can be staged as follows. The first stage is related to the arrival of the 10 Hungarian tribes from the northern part of Europe and the conquest of the 11 territory between the eastern Alps and the Dniester. The second stage is the 12 period between the Christianization of the Hungarian King Stephen and the 13 arrival of the Angevins. The second and the third period, post-Angevin or 14 better Sigismundian-Lazarević are, are epochs of colonization of different 15 population from the Germanic, North Pontic or Balkan space that are 16 integrated into the noble structure of the Kingdom, consolidating its 17 authority. The expansion of Serbian civilization after the claim to the throne 18 of Hungary of the Serbian King Stefan Dragutin when Árpád dynasty came 19 to end. Thus, the medieval Romanian Orthodox states, The Romanian 20 Country-Wallachia and Moldavia are the rest of Andrew III’s, the last 21 Árp{dian’s posterity, of his Serbian posterity, and catholic Hungary, the rest 22 of his Angevin Posterity. -

University of Copenhagen

The self-proclaimed Montenegrin Orthodox Church A paper tiger or a resurgent church? Hilton Saggau, Emil Published in: Religion in Contemporary Society/ Publication date: 2017 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Hilton Saggau, E. (2017). The self-proclaimed Montenegrin Orthodox Church: A paper tiger or a resurgent church? In M. Blagojevic, & Z. Matic (Eds.), Religion in Contemporary Society/ (pp. 31-54). Institute of Social Sciences, Department of Education and Culture,Serbian Orthodox Diocese of Branicevo, Pozarevac. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Emil Hilton Saggau Univezity of Copehagen Sektion for Church History The self-proclaimed Montenegrin OrthodoX Church – A paper tiger or A resurgent church? Abstract: During the early nineties, a so-called nationalized and traditional Orthodox community has been revived in the republic of Montenegro. This community calls itself the Montenegrin Orthodox Church and claims to be the representative of a resurgent form of the traditional Orthodox Church in Montenegro, which according to themselves vanished in the formation of Yu- goslavia in 1918. Since 1993 they have therefore tried to claim local traditions, customs and places as part of their revitalized “Montenegrin” version of East- ern Orthodoxy. Up until now the research on this community has been limited and has only focused on the – often violent – struggle between this community and the Ser- bian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral. It is difficult to grasp the reach and extent of the Montenegrin Orthodox Church in these studies – is the community a paper tiger or an actual existing and thriving church? This study will focus on a selection of religio-sociological key findings on this community in order to provide a more nuanced description of them. -

Knjiga ENGLESKI Layout 1

АSSOCIATION OF FAMILIES OF KIDNAPPED AND MISSING PERSONS IN KOSOVO AND METOHIJA ABDUCTED TRUTH Monograph is published on the occasion of 17 YEARS SINCE THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE ASSOCIATION OF FAMILIES OF KIDNAPPED AND MISSING PERSONS IN KOSOVO AND METOHIJA BELGRADE, 2017. ABDUCTED TRUTH 1 ABDUCTED TRUTH he Association of Families of Kidnapped and Missing persons in Kosovo − Metohija (hereinafter referred to as Association) was established Monograph of Association of Families of Kidnapped and Missing Persons in Kosovo - Metohija on 14 March 2000 with its main office in Belgrade and sub-offices in Niš, Kraljevo, Gračanica, Kosovska Mitrovica and Velika Hoča. Unsuccessful, months-long individual attempts of famillies to find their relatives who disappeared in a situation of general violence in T Kosovo − Metohija was the main impetus for this Association to be established. Kidnappings and disappearances of our family members took place everywhere. They were kidnapped under threat on the streets, from their workplaces (hospitals, factories, offices, etc.), on the roads (from trains, buses, cars). Upon the establishment of the Association, our first task was to gather data on missing persons, circumstances of their disappearances and to make a list of kidnapped and missing persons based on reports of families of internaly displaced persons from Kosovo – Metohija, where violence continued to spread like a wildfire. In 2004, the Association began to publish and send free copies of the magazine Kidnapped Truth to the addresses of kidnapped and -

The Confessor's Tongue for April 29, A. D. 2018

The Confessor’s Tongue for April 29, A. D. 2018 Fourth Sunday of Pascha: Paralytic In honor of St. Maximus the Confessor, whose tongue and right hand were cut off in an attempt by compromising authorities to silence his uncompromising confession of Christ’s full humanity & divinity. Le Midfeast Pentecost From Thrace in Greece, the peasant Timothy was On Wednesday of the fourth week we celebrate married and had two daughters. At this time, in the the Mid-Feast of Pentecost, i.e. half of the period early 1800s, shortly before the Greek Revolution, from Pascha to Pentecost. This day we commemorate Thrace was ruled by Muslim Turks. A Muslim that event from the life of the Savior, when He on the neighbor conceived a lust for Timothy’s wife, and, Mid- feast of the Tabernacles taught in the temple unable to contain his passion, he took her away by about His Own Divine ministry and the mystery of force. Somehow he persuaded her to become a water, under which we understand the beneficial Muslim and to be added to his harem. teaching of Christ and the beneficial gifts of the Holy Timothy, whose given name was Triantaphylos, Spirit. was deeply grieved by his wife’s double tragedy of The last, the eighth, day of the Old Testament losing both her marriage and her faith. As Christians feast of the Tabernacles, commemorating the forty under the Turkish yoke had no legal rights in such year wandering of the Jews in the desert (that is why cases against Muslims, he had no hope of getting her the people during this feast lived in tabernacles, i.e.