~I~ E DO NOT REMOVE from IFES RESOURCE CENTER! I' //:IES International Foundation for Election Systems I ~ 110115Th STREET, NW.' THIRD Floor ' WASHINGTON, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITE DES SCIENCES ET TECHNOLOGIES DE LILLE 1 Faculté Des Sciences Economiques Et Sociales Institut De Sociologie

N° d’ordre : 4311 UNIVERSITE DES SCIENCES ET TECHNOLOGIES DE LILLE 1 Faculté des Sciences Economiques et Sociales Institut de Sociologie Doctorat Changement social – option Ethnologie Mélanie SOIRON LA LONGEVITÉ POLITIQUE. Ou les fondements symboliques du pouvoir politique au Gabon. Sous la direction de Rémy BAZENGUISSA-GANGA Professeur de Sociologie, Université de Lille 1 Membres du Jury : Joseph TONDA (rapporteur et Président du Jury), Professeur de Sociologie et d’Anthropologie, Université de Libreville, Gabon. André MARY (rapporteur), Professeur d’Anthropologie. Directeur de recherches au CNRS. Alban BENSA, Professeur d’Anthropologie. Directeur d’études à l’EHESS. Bruno MARTINELLI, Professeur d’Anthropologie, Université de Provence. Thèse soutenue publiquement le 28 janvier 2009 Tome 1 sur 2 Résumé A partir d’une question initiale portant sur les raisons de la longévité politique du président de la République gabonaise, nous avons mis en lumière les fondements symboliques du pouvoir politique au Gabon. Ceux-ci sont perceptibles au sein des quatre principales institutions étatiques. Ainsi, une étude détaillée des conditions de création, et d’évolution de ces institutions, nous a permis de découvrir la logique de l’autochtonie au cœur de l’Assemblée nationale, celle de l’ancestralité au sein du Sénat, tandis qu’au gouvernement se déploie celle de la filiation (fictive et réelle), et que le symbolisme du corps présidentiel est porté par diverses représentations. A ce sujet, nous pouvons distinguer d’une part, une analogie entre les deux corps présidentiels qui se sont succédés et d’autre part, le fait que le chef de l’Etat actuel incarne des dynamiques qui lui sont antérieures et qui le dépassent. -

Jeremy Mcmaster Rich

Jeremy McMaster Rich Associate Professor, Department of Social Sciences Marywood University 2300 Adams Avenue, Scranton, PA 18509 570-348-6211 extension 2617 [email protected] EDUCATION Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. Ph.D., History, June 2002 Thesis: “Eating Disorders: A Social History of Food Supply and Consumption in Colonial Libreville, 1840-1960.” Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Phyllis Martin Major Field: African history. Minor Fields: Modern West European history, African Studies Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. M.A., History, December 1994 University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. B.A. with Honors, History, June 1993 Dean’s List 1990-1991, 1992-1993 TEACHING Marywood University, Scranton, PA. Associate Professor, Dept. of Social Sciences, 2011- Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN. Associate Professor, Dept. of History, 2007-2011 Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN. Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, 2006-2007 University of Maine at Machias, Machias, ME. Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, 2005-2006 Cabrini College, Radnor, PA. Assistant Professor (term contract), Dept. of History, 2002-2004 Colby College, Waterville, ME. Visiting Instructor, Dept. of History, 2001-2002 CLASSES TAUGHT African History survey, African-American History survey (2 semesters), Atlantic Slave Trade, Christianity in Modern Africa (online and on-site), College Success, Contemporary Africa, France and the Middle East, Gender in Modern Africa, Global Environmental History in the Twentieth Century, Historical Methods (graduate course only), Historiography, Modern Middle East History, US History survey to 1877 and 1877-present (2 semesters), Women in Modern Africa (online and on-site courses), Twentieth Century Global History, World History survey to 1500 and 1500 to present (2 semesters, distance and on-site courses) BOOKS With Douglas Yates. -

Etat D'avancement Des Travaux De These

UNIVERSITE BORDEAUX SEGALEN FACULTE DES SCIENCES DU SPORT ET DE L’EDUCATION PHYSIQUE ECOLE DOCTORALE DES SCIENCES SOCIALES. (E.D. 303) Année : 2011 Thèse n° : 1838 ETUDE DE L’ORGANISATION ET DU FONCTIONNEMENT DES INSTITUTIONS SPORTIVES AU GABON. GENESE ET ANALYSE PROSPECTIVE D’UNE POLITIQUE PUBLIQUE THESE POUR LE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE DE BORDEAUX SEGALEN Mention : Sciences et Techniques des Activités Physiques et Sportives STAPS Présentée et soutenue publiquement par : Célestin ALLOGHO-NZE Sous la Direction de Madame Marina HONTA Et Monsieur Jean-Paul CALLEDE Membres du Jury - Mr Gilles FERREOL, Professeur Université de Franche-Comté, Président - Mr Pierre CHAZAUD, Professeur Université de Lyon 1, Rapporteur - Mr Dominique CHARRIER, Maître de conférences HDR Université Paris Orsay, Rapporteur - Mr André MENAUT, Professeur Université Bordeaux Segalen - Mr Jean-Paul CALLEDE, Chargé de recherche CNRS, MSHA Co Directeur - Mme Marina HONTA, Maître de conférences HDR Université Bordeaux Segalen Co Directrice Bordeaux, Novembre 2011 1 ETUDE DE L’ORGANISATION ET DU FONCTIONNEMENT DES INSTITUTIONS SPORTIVES AU GABON GENESE ET ANALYSE PROSPECTIVE D’UNE POLITIQUE PUBLIQUE RESUME Les activités physiques, et les jeux traditionnels font partis de la culture universelle, et appartiennent à l’humanité. Les peuples d’Afrique ont dû abandonner les leurs avec l’arrivée des sports modernes pendant la période de colonisation. Les activités physiques et jeux traditionnels du Gabon avaient dans la plus part des cas un but utilitaire allant de la préparation physique des jeunes au service de la communauté, aux activités de loisirs pour tous comme des danses lors des évènements commémoratifs ou des cérémonies rituelles et initiatiques. -

The World Factbook

The World Factbook Africa :: Gabon Introduction :: Gabon Background: El Hadj Omar BONGO Ondimba - one of the longest-serving heads of state in the world - dominated the country's political scene for four decades (1967-2009) following independence from France in 1960. President BONGO introduced a nominal multiparty system and a new constitution in the early 1990s. However, allegations of electoral fraud during local elections in 2002-03 and the presidential elections in 2005 exposed the weaknesses of formal political structures in Gabon. Following President BONGO's death in 2009, new elections brought Ali BONGO Ondimba, son of the former president, to power. Despite constrained political conditions, Gabon's small population, abundant natural resources, and considerable foreign support have helped make it one of the more prosperous and stable African countries. Geography :: Gabon Location: Central Africa, bordering the Atlantic Ocean at the Equator, between Republic of the Congo and Equatorial Guinea Geographic coordinates: 1 00 S, 11 45 E Map references: Africa Area: total: 267,667 sq km country comparison to the world: 77 land: 257,667 sq km water: 10,000 sq km Area - comparative: slightly smaller than Colorado Land boundaries: total: 2,551 km border countries: Cameroon 298 km, Republic of the Congo 1,903 km, Equatorial Guinea 350 km Coastline: 885 km Maritime claims: territorial sea: 12 nm contiguous zone: 24 nm exclusive economic zone: 200 nm Climate: tropical; always hot, humid Terrain: narrow coastal plain; hilly interior; savanna -

Journée De Souvenir Du Décès De Feu Pierre Mamboundou Resserrer Les Rangs Pour Les Futures Échéances

Mardi 17 Octobre 2017 2 P o l i t i q u e Journée de souvenir du décès de feu Pierre Mamboundou Resserrer les rangs pour les futures échéances J-C. A Libreville/Gabon réflexion, les participants l’entrée de Sébastien Mam- base et d’un protocole d’ac- C’est l’une des consignes ont suivi avec attention boundou Mouyama au cord écrit avec le pouvoir. que le président du parti, quatre communications gouvernement mis en Toutefois, ont poursuivi les Mathieu Mboumba Nzie- n portant sur l’historique de place après les Accords de deux anciens ministres, si o i n gnui, a donnée aux mili- U l’UPG, le cadre juridique, la Paris (…) et le décès le 15 l’entrée au gouvernement ' L tants. récente participation au octobre 2011 de Pierre ne peut être l’occasion de / A C J gouvernement de deux de Mamboundou. résoudre tous les pro- : o ses dirigeants, la crise poli- Pour le deuxième thème, la blèmes du parti (…), il n’en t o "Journée de souve- h DÉBUTÉES tique et le climat au sein du Commissaire déléguée aux demeure pas moins que P parti. Affaires sociales a fait ob- dniers d aec tfeioun Psi eimrrpeo Mrtaamntbeosu enn- Une vue du directoire de l'UPG à l'ouverture des Pour ce qui est de l’histo- server que le commissaire sdao ufa"veur ont été posées. journées de réflexion. rique de l'UPG, son prési- général à l’Éthique a du Dimanche, était célébrée la dent, Mathieu Mboumba mal à remplir sa mission, sixième le 10 octobre Nziengui est revenu sur les faute de budget et d’une par des journées de ré- moments forts qui ont absence de rigueur dans , sur l'esplanade du flexion, les festivités mar- marqué la vie du parti: sa l’application des règles sta- siège d'Awendjé. -

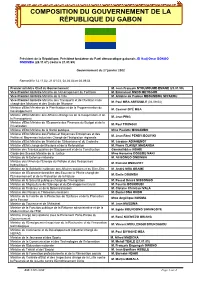

Composition Du Gouvernement De La République Du Gabon

COMPOSITION DU GOUVERNEMENT DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE DU GABON Président de la République, Président fondateur du Parti démocratique gabonais, El Hadj Omar BONGO ONDIMBA (28.11.67) (réélu le 21.01.99) Gouvernement du 27 janvier 2002 Remanié le 12.11.02, 21.01.03, 02.04.03 et 04.09.04 Premier ministre Chef du Gouvernement M. Jean-François NTOUMOUME-EMANE (23.01.99) Vice-Premier ministre Ministre de l'Aménagement du Territoire M. Emmanuel ONDO METOGHO Vice-Premier ministre Ministre de la Ville M. Antoine de Padoue MBOUMBOU MIYAKOU Vice-Premier ministre Ministre des Transports et de l'Aviation civile M. Paul MBA ABESSOLE (04.09.04) chargé des Missions et des Droits de l'Homme Ministre d'Etat Ministre de la Planification et de la Programmation du M. Casimir OYÉ MBA Développement Ministre d'Etat Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la Coopération et de M. Jean PING la Francophonie Ministre d'Etat Ministre de l'Economie des Finances du Budget et de la M. Paul TOUNGUI Privatisation Ministre d'Etat Ministre de la Santé publique Mme Paulette MISSAMBO Ministre d'Etat Ministre des Petites et Moyennes Entreprises et des M. Jean-Rémi PENDY-BOUYIKI Petites et Moyennes Industries Chargé de l'Intégration régionale Ministre d'Etat Ministre de l'Habitat de l'Urbanisme et du Cadastre M. Jacques ADIAHENOT Ministre d'Etat chargé de Missions et de la Refondation M. Pierre CLAVER MAGANGA Ministre des Travaux publics de l'Equipement et de la Construction Général Idriss NGARI Garde des Sceaux Ministre de la Justice Mme Honorine DOSSOU NAKI Ministre de la Défense nationale M. -

1999 Page 1 of 14

U.S. Department of State, Human Rights Reports for 1999 Page 1 of 14 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. 1999 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor U.S. Department of State, February 25, 2000 GABON Gabon is a republic dominated by a strong Presidency. Although opposition parties have been legal since 1990, a single party, the Gabonese Democratic Party (PDG) has remained in power since 1968 and has circumscribed political choice. Elections for the presidency and the National Assembly generally have not been free and fair but have varied widely in quality; some suffered chiefly from poor organization, while others were fraudulent. PDG leader El Hadj Omar Bongo has been President since 1967 and was reelected for another 7-year term in a December 1998 election marred by irregularities that generally favored the incumbent, including incomplete and inaccurate electoral lists and the use of false documents to cast votes. In July 1998, following opposition victories in 1996 elections for local government offices that recently had been made elective, the Government transferred key electoral functions to the Interior Ministry from an independent National Electoral Commission that had been established pursuant to a 1995 constitutional referendum. -

Tab Number: 10

Date Printed: 11/03/2008 JTS Box Number: IFES 4 Tab Number: 10 Document Title: Evaluation Technique Pre-Electorale au Gabon du 8 au 25 Octobre Document Date: 1999 Document Country: Gabon IFES ID: R01604 -DO NOT REMOVE FROM IFES RESOURCE CENTER! I I I I Evaluation technique preelectorale au Gabon ,. du 8 au 25 octobre 1998 I. Mars 1999 I I 'I I I I I, I I 'I J I' I I, I I IFES Fondation lnternationale pour les Systemes Electoraux I nOI 15th Street, N.W. 3rd Floor Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 828-8507 FAX (202) 452-0804 I ·1 I Evaluation technique pn!clectorale au Gabon I du 8 au 25 octobre 1998 I I I Mars 1999 'I I I I Ce rapport a ete [manre par USAlD par I'intermediaire de l'Accord de cooperation n° AEP-5468-A- I 00-5038-00. I I I I I TABLE DES MATIERES I I. RESUME ............................................................................................................................. 1 I II. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 III. CONTEXTE ........................................................................................................................ 6 I A. DONNEES HISTORIQUES .................................................................................... 6 I B. LA DEMOCRA TIE AU GABON: 1990-1998 .................................................... .1 0 IV. CADRE LEGAL ................................................................................................................ 16 A. Lois principaIes ..................................................................................................... -

La Mobilisation Politique Transnationale Pour Une Alternance Démocratique Au Gabon Par Delphine Lecoutre PAGE 2

BulletinFrancoPaix Vol. 5, n° 7 Septembre 2020 La mobilisation politique transnationale pour une alternance démocratique au Gabon Par Delphine Lecoutre PAGE 2 Décryptage. Burkina Faso : des élections dans un contexte de fragilité particulier PAGE 11 Nouvelles et annonces PAGE 13 ARTICLE La mobilisation politique transnationale pour une alternance démocratique au Gabon : opposition politique, société civile et diaspora (2009-2016) Par Delphine Lecoutre RÉSUMÉ EXÉCUTIF Le décès du président Omar Bongo Ondimba en 2009, après 42 ans au pouvoir, a fait naître une réelle effervescence politique et a favorisé une mobilisation civique tant au Gabon que dans la diaspora. Son fils Ali Bongo Ondimba est devenu chef de l’État la même année suite à une élection contestée. L’opposition, la société civile locale et la diaspora se sont mobilisées Delphine Lecoutre depuis 2009 pour mener des actions collectives transnationales visant à provoquer une alternance démocratique au Gabon. La période 2009-2016 est révélatrice des ambitions, du mode opératoire et des faiblesses de ces Politologue africaniste acteurs. Enseignante au Centre d’études Entre 2009 et 2015, André Mba Obame ou « AMO » chercha par tous diplomatiques et stratégiques les moyens à contraindre le président Ali Bongo Ondimba à entamer des et au Centre international de négociations avec l’opposition : il tenta une mutualisation transnationale des acteurs d’opposition. formation de l’École militaire de Saint Cyr Coetquidan, France L’une des erreurs d’« AMO » est probablement de n’avoir pas compris qu’Ali Bongo Ondimba n’était pas un homme de compromis, mais plutôt un Coordinatrice et porte-parole adepte du clivage et de la confrontation. -

Rapport De La Mission D'observation De L'election

RAPPORT DE LA MISSION D’OBSERVATION DE L’ELECTION PRESIDENTIELLE AU GABON : SCRUTIN DES 25 ET 27 NOVEMBRE 2005. ________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Son Excellence Monsieur Abdou Diouf, Secrétaire général de l’Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, a décidé de répondre favorablement à la demande de Monsieur le Ministre de l’Intérieur de la République du Gabon en vue de l’envoi d’une Mission d’observation à l’occasion de l’élection présidentielle des 25 et 27 novembre 2005. Depuis le retour au multipartisme, au début des années 1990, c’est la troisième fois qu’était organisée une élection présidentielle au Gabon, conformément aux articles 4, 9 et 10 de la Constitution du 26 mars 1991, révisés le 19 août 2003, l’article 4 nouveau disposant que l’élection présidentielle a lieu selon le système du scrutin majoritaire à un tour et l’article 9 nouveau disposant que le Président de la République peut être candidat à sa propre succession autant de fois qu’il le souhaite. La Mission d’observation francophone est arrivée à Libreville le 23 novembre dans la matinée. Elle a quitté la ville le 29 novembre dans la soirée. Elle était composée de la façon suivante : • Chef de la Délégation et porte parole Monsieur Pierre FIGEAC Secrétaire permanent honoraire de l’AIMF Membre du Conseil Economique et Social FRANCE • Membres Monsieur Pandeli VARFI Membre de la Commission Electorale Centrale ALBANIE Monsieur Sébastien AGBOTA Journaliste Ancien Vice-Président de la HAAC BENIN Madame Imelda NZIRORERA -

Preliminary Statement Gabon August 2016

JOINT AFRICAN UNION AND ECONOMIC COMMUNITY OF CENTRAL AFRICAN STATES ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION FOR THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN THE REPUBLIC OF GABON – 27 AUGUST 2016 PRELIMINARY STATEMENT I. INTRODUCTION 1- Following the decision of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission (AUC), HE Dr. Nkosazana Dlamini ZUMA and HE Mr. Ahmad ALLAM-MI, Secretary General of the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), a joint AU-ECCAS mission was deployed for the presidential election held on August 27, 2016 in the Republic of Gabon. 2- The Joint Mission is led by the Excellencies Mr. Cassam UTEEM, former President of the Republic of Mauritius and Mr. Abou MOUSSA, former Special Representative of the UN Secretary General for Central Africa. It is composed of ambassadors accredited to the African Union in Addis Ababa, members of the Pan African Parliament, heads of electoral commissions, electoral experts and members of African civil society organisations. 3- The joint mission includes seventy-five (75) observers including twelve (12) long-term observers deployed since 7 August 2016. The observers come from thirty-two (32) African countries.1 4- The evaluation of the election was based on the relevant provisions of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (2012) the Declaration of the OAU / AU Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa (2002), the 2002 AU's Guidelines for 1 Angola, Algéria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroun, Cape Verde, Congo, Comores Islands, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Libéria, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Saharawi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Mauritius, Republic of Sao Tomé and Principe, Rwanda, Sénégal, Seychelles, Chad, Togo et Tunisia. -

2016 Country Review

Gabon 2016 Country Review http://www.countrywatch.com Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 3 Gabon 4 Africa 5 Chapter 2 7 Political Overview 7 History 8 Political Conditions 9 Political Risk Index 23 Political Stability 38 Freedom Rankings 53 Human Rights 65 Government Functions 67 Government Structure 69 Principal Government Officials 72 Leader Biography 73 Leader Biography 73 Foreign Relations 77 National Security 82 Defense Forces 83 Chapter 3 85 Economic Overview 85 Economic Overview 86 Nominal GDP and Components 88 Population and GDP Per Capita 90 Real GDP and Inflation 91 Government Spending and Taxation 92 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 93 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 94 Data in US Dollars 95 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 96 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 97 World Energy Price Summary 98 CO2 Emissions 99 Agriculture Consumption and Production 100 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 102 Metals Consumption and Production 103 World Metals Pricing Summary 105 Economic Performance Index 106 Chapter 4 118 Investment Overview 118 Foreign Investment Climate 119 Foreign Investment Index 122 Corruption Perceptions Index 135 Competitiveness Ranking 147 Taxation 156 Stock Market 157 Partner Links 157 Chapter 5 158 Social Overview 158 People 159 Human Development Index 162 Life Satisfaction Index 166 Happy Planet Index 177 Status of Women 186 Global Gender Gap Index 188 Culture and Arts 198 Etiquette 199 Travel Information 199 Diseases/Health Data 209 Chapter 6 216 Environmental Overview 216 Environmental Issues 217 Environmental Policy 218 Greenhouse Gas Ranking 219 Global Environmental Snapshot 230 Global Environmental Concepts 241 International Environmental Agreements and Associations 255 Appendices 280 Bibliography 281 Gabon Chapter 1 Country Overview Gabon Review 2016 Page 1 of 293 pages Gabon Country Overview GABON Gabon is one of West Africa's more stable countries.