Mangroves Occurring on the Many Islands in the South Pacific Are Only a Small Component When Compared to the Worldwide Inventory of Mangroves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008

OCHA Regional Office for Asia Pacific Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008 OCHA Presence in the Pacific Northern Papua New Guinea Fiji Mariana Humanitarian Affairs Unit (HAU), PNG Regional Disaster Response Islands (U.S.) UN House , Level 14, DeloitteTower, Advisor (RDRA), Fiji Douglas Street, PO Box 1041, 360 Victoria Parade, 3rd Floor Fiji +10 Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Development Bank Building, Suva, FIJI Tel: +675 321 2877 Tel: +679 331 6760, +679 331 6761 International Date Line Fax: +675 321 1224 Fax: +679 330 9762 Saipan Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Head: Vini Talai Head: Peter Muller Agana +12 Guam (U.S.) Pacific Ocean +10 MARSHALL ISLANDS Legend Depth (m) OCHA Presence Below 5,000 1,001 to 2,000 MICRONESIA (FSO) Koror Majuro Country capital Palikir 4,001 to 5,000 501 to 1,000 Territory capital PALAU +11 Illustrative boundary 3,001 to 4,000 101 to 500 +9 +10 Time difference with UTC 2,001 to 3,000 o to 100 Tarawa (New York: UTC -5 Equator NAURU Geneva: UTC +1) IMPORTANT NOTE: The boundaries on this map are for illustrative purposes only Yaren Naming Convention and were derived from the map ’The +12 +12 KIRIBATI UN MEMBER STATE Pacific Islands’ published in 2004 by the Territory or Associated State Secretariat of the Pacific Community. INDONESIA TUVALU -11 -10 PAPUA NEW GUINEA United Nations Office for the Coordination +10 +12 of Humanitarian affairs (OCHA) Funafuti Toke lau (N.Z.) Regional Office for Asia Pacific (ROAP) Honiara Executive Suite, 2nd Floor, -10 UNCC Building, -

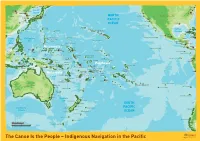

Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific

Hokkaido Vladivostok New York Philadelphia Beijing North Korea Sea of Tianjin Japan P'yongyang Sacramento Washington Seoul Japan Honshu NORTH San Francisco United States of America China South Tokyo Nagoya Korea Pusan Osaka Los Angeles PACIFIC Cheju-Do Shikoku San Diego Shanghai Kyushu OCEAN New Orleans Guadalupe Island (Mex.) Midway Baja Ryukyu Ogasawara- Islands (US) California Trench Okinawa-Jima (Jap.) Gunto (Jap.) Gulf of Miami Minami-Tori- Hawaiian Islands (US) Shima (Jap.) Mexico Havana Taiwan Kauai Cuba Oahu Mexico Hainan Dao Honolulu Guadalajara Jamaica Mariana Mexico Northern Wake Island (US) Hawaii Revillagigedo Island (Mex.) Kingston Philippine Ridge Belize South Luzon Mariana Islands Johnston Atoll (US) China Sea (US) Guatemala Honduras Manila Saipan Sea Guam (US) Marshall Islands El Salvador Nicaragua Philippines Enewetak Managua Costa Rica Panama Yap Islands Micronesia San José Palawan Ratak Clipperton Island (Fr.) Mindanao Pohnpei Chain Davao Melekeok Satawai Panama Chuuk Palikir Majuro Palmyra Atoll (US) Ralik Cocos Islands (CR) Brunei Palau Kosrae Chain Malaysia Line Malpelo Island (Col.) Federated States of Micronesia Gilbert Islands Howland Island (US) Islands Colombia Halmahera Kalimantan Tarawa Baker Island (US) Bismarck Archipelago Quito Jarvis Island (US) Galapagos Islands (Ec.) Sulawesi New Ireland Nauru Guayaquil Phoenix Islands Kiribati Malden Rabaul Ecuador Seram New Guinea Papua Bougainville Solomon Nanumea Vaiaku Indonesia New Guinea New Britain Santa Isabel Islands Polynesia Surabaya Funafuti Marquesas Islands -

Solomon Islands B ! Fagani C D ! Waimapuru ! ! Solomon Sea Mainga Tawani Vanuatu ! ! Rennel Island Manakia

FRAME B 155°E 160°E Rorovana ! ! ! Torokina Panguna Karakun Koiaris ! ! Papua New Guin! ea Taki ! ! Jaba Sininai ! Pupuku PACIFIC OCEAN Aitara ! ! ! Kaekui Mission ! Birambira ! Tokuaka Susuka !Kombokisa !! Kutakana Lukuvaru Shortland Island PACIFIC OCEAN ! ! Ghaomai Choiseul Zambanarungga Shortland I ! ! Vure ! Trevanion Noka ! ! Mono I Matamotu ! ! ! Masoko Java Malemgeulu ! ! Paraso ! Zuzuao Santa Cruz Islands Apakhö ! ! ! Point Lunga ! Eleoteve Arambu Filuo Vana!! ! ! Litoghahira Sambora Santa Isabel Island FRAME D Kolomb!angara! Ganongga ! New Georgia Islands ! Tapurai Tuarugu ! Biluro ! ! Mburuku Loalonga ! Lokiha ! ! ! Sepi ! Ageraba Harai Mbareho ! Fokinkorra ! S o l o m o n I s l a n d s Auki Kunura ! ! Kwaimbaambaala ! Vura Nggaulai'ato'o ! ! ! Siota !! Manikiriu Tulagi Paunairo Vatupilei ! ! Palikir Abungari !. Koror !. Marshall Islands Malaita Palau Guranja Honiara Micronesia Hularu ! ! .! !Gembua ! Guadalcanal Rere ! Kiribati ! ! PACIFIC OCEAN Solomon Sea Mbaole ! Sitaronda Ahenawai Anoni'usu Nauru Ralavu Raurembo ! Mwarada ! ! ! Ione ! Lakatana ! Ahia I n d o n e s i a Makina 10°S Papua New 10°S Guinea Solomon Sea Honiara Heuru !. Port Moresby !. ! Etamarorai Solomon Islands B ! Fagani C D ! Waimapuru ! ! Solomon Sea Mainga Tawani Vanuatu ! ! Rennel Island Manakia !.Port-Vila ! San Cristobal Australia Vinegau ! New Caledonia Na Wosi ! Funakumwa ! ! !. Hauraha Nouméa FRAME A Napasiwai FRAME C 155°E 160°E Date Created: 04- JUL - 2011 Map Num: LogCluster_SLB_LCA_004 Kilometers .! National Capital Road Network National Boundary Coord.System/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 S O L O M O N GLIDE Num: ! Village (selection) Secondary Surface Waterbody The boundaries and names and the designations 0 50 100 150 200 used on this map do not imply official endorsement I S L A N D S FRAME A Nominal Scale 1:62,420,000 at A4 Tertiary or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Micronesian Art Historical Research and Library Collection Resources in Micronesia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 377 132 SO 024 616 AUTHOR Haynes, Douglas TITLE Micronesian Art Historical Research and Library Collection Resources in Micronesia. PUB DATE Nov 91 NOTE 9p.; Paper presented to the Art Education Delegation Exchange (Beijing, China, November 1991). PUB TYPE Reference Materials General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Architecture; Archives; *Art History; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Library Collections; *Non Western Civilization IDENTIFIERS Micronesia ABSTRACT This paper briefly describes the geographic region and some indigenous artifacts of Micronesia. The state of art historical research in the area and currently available library resources are discussed. Micronesia is comprised of seven island nations peopled by distinctly unique cultural groups. Study of Micronesian art and architecture is relatively recent. Early work was done by German, then Japanese, expeditions. More recently, Americans, as well as European and Japanese researchers, have studied the art and cultures of Micronesia. Among art forms studied are latte stones, dating from 1000 A.D. to 1668 A.D. These were hand smoothed and fitted limestone columns and capstones used to construct A-frame houses for the Chamorros, a people of the Mariana Islands group. The bai, a communal village house of Palau, is decorated with sculpture:, expressing a complex iconography of mythological symbolism. Another architectural accomplishment of Micronesians are the stone cities of Pohnpei and Kosrae, dating from the 8th-9th centuries to 1830. The largest collection of Micronesian art history materials available in the islands is the collection at the University of Guam (Mangilao). Other collections are located in the Pal=su National Museum Library in Koror, Palau; the Community College of Micronesia Pacific Collection in Kolonia, Pohnpei; The Nieves Flores Public Library in Agana, Guam; and the Federated States of Micronesia National Archives in Palikir, Pohnpe. -

Perry & Buden 1999

Micronesica 31(2):263-273. 1999 Ecology, behavior and color variation of the green tree skink, Lamprolepis smaragdina (Lacertilia: Scincidae), in Micronesia GAD PERRY Brown Tree Snake Project, P.O. Box 8255, MOU-3, Dededo, Guam 96912, USA and Department of Zoology, Ohio State University, 1735 Neil Ave., Columbus, OH 43210, USA. [email protected]. DONALD W. BUDEN College of Micronesia, Division of Mathematics and Science, P.O. Box 159, Palikir, Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia 96941 Abstract—We studied populations of the green tree skink, Lamprolepis smaragdina, at three main sites in Micronesia: Pohnpei (Federated States of Micronesia, FSM) and Saipan and Tinian (Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, CNMI). We also surveyed Rota (CNMI), where the skink has not been recorded in previous surveys, to verify its absence. Our main goal was to describe some basic biology traits at these sites. Observations were carried out between 1993 and 1998. We used focal animal observations and visual surveys to describe the relative abundance, elevational distribution, behavior (perch choice, foraging behavior, activity time), and coloration of the species at each of the three sites. This information was then used to compare these populations in order to assess the origin of the CNMI populations. As expected, we found no green tree skink on Rota. We found few differences among the three populations we did locate, Pohnpei, Tinian, and Saipan. Perch diameters and body orientations were similar between the three sites, as were population densities and foraging behaviors. However, Tinian’s lizards perched lower than those of Pohnpei or Saipan, probably due to the smaller trees available to them. -

Annex C: LIST of PARTICIPANTS

Annex C: LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Country Representatives Cook Islands Koroa Raumea Ministry of Marine Resources Cook Islands Tel: +682 28730 Director, Inshore Fisheries and Aquaculture P.O. Box 85 Fax: +682 29721 Rarotonga Email: [email protected] Cook Islands Ben Ponia Ministry of Marine Resources Cook Islands Tel: +682 28730 Secretary PO Box 85 Fax: +682 29721 Rarotonga Email: [email protected] Cook Islands Federated States of Micronesia Valentin A. Martin Tel: (691) 320-2620 /2646 Deputy Assistant Secretary, Marine Federated States of Micronesia National Fax: +691 3205854 Resources Unit - Department of Resources & Government Email: [email protected] Development Pohnpei Palikir 96941 Federated States of Micronesia Eugene Pangelinan National Oceanic Resource Management Tel: (691) 320-2529 Deputy Director Authority Fax: (691) 320-2383 P.O Box PS122 Email: [email protected] Palikir Pohnpei 96941 Federated States of Micronesia Fiji Sanaila Naqali Ministry of Primary Industries & Sugar Tel: +679 3301611 Director of Fisheries PO Box 2218 Fax: +679 3308218 Government Buildings Email: [email protected] Suva Fiji Kiribati Beero Tioti Ministry of Fisheries Tel: +686 21099 Principal Fisheries Officer - Fisheries Divison and Marine Resources Development Fax: +686 21120 (Oceanic Fisheries Development) PO Box 64, Bairiki Email: [email protected] Tarawa Kiribati Marshall Islands No representative Nauru Monte Depaune Nauru Fisheries Tel: +674 4443733 Ag.Deputy Chief Executive Officer and Marine Resources Authority Fax: +674 4443812 PO Box 449 Email: [email protected] Aiwo District Nauru Dr Tim Adams Nauru Fisheries Tel: (674) 5573733 or (674) 5573135 Institutional Strengthening Project Manager and Marine Resources Authority Fax: +674 4443812 PO Box 449 Email: [email protected] Aiwo District Nauru Niue James Tafatu Department of Agriculture, Tel: +683 4302 Principal Fisheries Officer - Fisheries Division Forestry and Fisheries Fax: Alofi Email: [email protected] Niue Palau David A. -

Summary Information Bulletin Marshall Islands: Drought

Information bulletin Marshall Islands: Drought Information Bulletin n° 2 GLIDE n° 2013-000053-MHL 7 June 2013 This bulletin is being issued for information only and reflects the current drought situation and details available at this time within the Republic of Marshall Islands (RMI). The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is working with the RMI Government and other key international actors to identify the support required for the drought response and early recovery. Assistance being provided by IFRC is in partnership with New Zealand Red Cross, Kiribati Red Cross Society and Australian Red Cross. IFRC is currently analyzing the possibility of launching an Emergency Appeal. Mobilization of Reverse Osmosis (RO) units to drought- <click here to view the map of the affected area, or affected atolls. Photo Cred: IFRC here for detailed contact information> Summary Due to an extended dry period, the RMI Government declared a state of emergency for the northern areas of the RMI on 19 April 2013, which was followed by a declaration of a state of disaster on 8 May for 13 atolls/islands. The disaster assessments undertaken have identified that the communities in these northern atolls/islands are being severely affected by the drought and face potential health, environmental, social and economic hardship, due to the persistent dry weather. The most pressing humanitarian needs are access to safe water and the growing need for food due to local crop failure. Villages have had to ration water to preserve supplies, and the number of affected atolls/islands has since increased from 13 to 15. -

Developing the EHDI Database Systems in the Federated States of Micronesia

Developing the EHDI Database Systems in the Federated States of Micronesia 13th Annual EHDI Conference, April 13-15, 2014, Jacksonville, FL Dionis Saimon Department of Health & Social Affairs Government of the Federated States of Micronesia Velma A. Sablan, Ph.D. Project Evaluator & Technical Consultant FSM-EHDI Project Sue Scanlan, FamilyTrac Chuck Scheier, FamilyTrac Acknowledgements FSM EHDI Team Dr. Vita Skilling Dr. Anamaria Yomai Stanley Mickey Arthur Albert Vicky Nimea Joseph Lukan Objectives ● Challenges ● The decision-making process ● Assess current status Geographical makeup of FSM Dionis Saimon Where is the Federated States of Micronesia? FSM-China 3,950 Miles FSM-Guam 1,020 Miles FSM-California 5,518 Miles FSM-Australia 2,766 Miles How do you get there? The “Island Hopper” Some FACTS about the FSM… • FSM has 4 Sta tes: Pohnpei State, Kosrae State, Chuuk State, & Yap State • FSM has a Compact of Free Association with the United States. Its citizens serve in the U.S. Military and FSM qualifies for U.S. Federal assistance • FSM has a total population of approximately 107,008 as of 2011 and 2,200 average births per year • FSM National Government is located in Palikir in Pohnpei State • FSM-EHDI National is located in the Department of Health and Social Affairs in Palikir • Each FSM State has its own State EHDI Program Understanding How Many Islands Really Compose the FSM ……but a closer look at each State is needed to understand the many challenges! The Many Islands of Yap State Main Island The Many Islands of Chuuk State Main Island Pohnpei State Palikir-National Government Kosrae State is a Single Island Historical Evolution and Decision Making Process Velma A. -

College of Micronesia-Fsm Student Center Expressions of Interest

GOVERNMENT OF THE FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA COLLEGE OF MICRONESIA-FSM STUDENT CENTER EXPRESSIONS OF INTEREST Date Posted: December 17, 2019 Procurement Type: Sources Sought Synopsis This announcement constitutes an Expressions of Interest where potential contractors can record their interest in this upcoming project of the FSM National Government. This is not a Request for Proposal (RFP). This announcement is for information and planning purposes only and is not to be construed as a commitment by the Government, implied or otherwise, to issue a solicitation of award or a contract. The Department of Transportation, Communications and Infrastructure requests letters of interest from PRIME CONTRACTORS interested in performing work to construct a Student Center at the National Campus located at Palikir, Pohnpei, FSM. Background The College of Micronesia-FSM is the region’s premier tertiary education level service provider and is currently on a drive to expand its campuses in order to cope with present and future demand. In light of this, the College of Micronesia-FSM through the National Government engaged suitable experts to prepare a detailed masterplan which is now informing the Programme rollout starting with the Student Center at the National Campus. Project Description This is a Design-Bid-Build fixed priced construction project to construct a two-storey student center located at the National Campus of the College of Micronesia in Palikir, Pohnpei. The magnitude of this project is estimated to be between $3,000,000.00 and $5,000,000.00. Interested PRIME CONTRACTORS should include the following with their letters of interest: 1. Name of firm with address, phone, and point of contact (email) 2. -

America's Pacific Island Allies

America’s Pacific Island Allies The Freely Associated States and Chinese Influence Derek Grossman, Michael S. Chase, Gerard Finin, Wallace Gregson, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Logan Ma, Jordan R. Reimer, Alice Shih C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2973 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0228-8 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover photo: Palau islands by Adobe Stock / BlueOrange Studio. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Located north and northeast of Australia and east of the Philippines, the Freely Associated States (FAS)—comprising the independent countries of the Republic of Palau, the Federated States of Microne- sia (FSM), and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI)—occupy an ocean area roughly the size of the continental United States. -

10 Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands 115 10 Marshall Islands Wake (US) Taongi 15° N MARSHALL ISLANDS Enewetak Bikini Rongelap Wotho 10° N Kwajalein Jemo Island Ujelang Maloelap Namu Jabwot Arno Atoll Palikir Majuro Pohnpei Jaluit Atoll Mili Atoll FEDERATED STATES OF 5° N POHNPEI KOSRAE Ebon STATE MICRONESIA STATE KIRIBATI Butaritari Marakei Abaiang 160° E 165° E NAURU 170° E Tarawa 175° E 10.1 Volumes and Values of Fish Harvests in Marshall Islands Coastal Commercial Catches in Marshall Islands The following represent the major historical attempts to consolidate infor- mation on coastal fisheries production in Marshall Islands: • Dalzell et al. (1996) used information from the FFA fisheries profiles (Smith 1992) and from a nutritional survey in 1990 (Anon. 1991) to estimate coastal commercial fisheries production for the early 1990s of 369 mt (worth US$714,504) and subsistence production of 2,000 mt (worth US$3,103,213). 116 Fisheries in the Economies of Pacific Island Countries and Territories • Gillett and Lightfoot (2001) considered the Dalzell estimate and seven other sources of information and then proposed coastal commercial fisheries production for the late 1990s of 444 mt (worth US$973,000) and subsistence production of 2,800 mt (worth US$3,836,000). • Gillett (2009) considered the above two estimates as well as the fol- lowing more recent information: (a) Information on the purchases of fish in the outer islands by Marshall Islands Marine Resource Author- ity (MIMRA), (b) The 2002 HIES, (c) OFCF fishery surveys, and (d) Data on the exports of products from coastal commercial fisheries. The study estimated that commercial fisheries production in Marshall Islands in the mid-2000s was about 950 mt, worth US$2.9 million. -

Cultural and Socioeconomic Determinants of Energy

Natural Resources Forum 38 (2014) 27–46 DOI: 10.1111/1477-8947.12030 Cultural and socio-economic determinants of energy consumption on small remote islands Manfred Lenzen, Murukesan Krishnapillai, Deveraux Talagi, Jodie Quintal, Denise Quintal, Ron Grant, Simpson Abraham, Cindy Ehmes and Joy Murray Abstract In this cross-country analysis of four small and remote islands, we integrate multiple dimensions of socio-economic demographic data, such as population, land area, remoteness, tourist arrivals and earnings, export earnings, financial support, average incomes, fuel and electricity prices, penetration of renewable energy sources, and motor vehicle usage; we compare these characteristics with per capita use of energy carriers such as electricity, petrol and diesel. From these characteristics, we identify key determinants of energy consumption in the islands. Whereas we focus on energy, our analysis also applies to emissions of carbon and energy-related pollutants. Our results indicate that cultural and social contexts are at least as relevant for policymaking as economic and technological aspects. We suggest that in small island developing States there is scope for policymaking to at the same time: reduce economic vulnerability due to dependence on imported fossil fuels; reduce environmental impact; and progress sustainable development. Such progress can be implemented through peer-to-peer learning programmes facilitated by targeted international cooperation and partnerships. Keywords: Energy determinants; energy consumption; small remote