Perry & Buden 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buden-Etal2005.Pdf

98 PACIFIC SCIENCE . January 2005 Figure 1. Location of the Caroline Islands. along the shore. The average annual rainfall spp.) are the dominant trees on all but the ranges from about 363 cm in Chuuk (Merlin smallest atoll islands, where coastal scrub and and Juvik 1996) to 1,015 cm estimated in the strand predominate. All of the islands fall mountains on Pohnpei (Merlin et al. 1992). within the equatorial rain belt and are wet The land area on the numerous, wide- enough to support a mesophytic vegetation spread, low (1–4 m high) coralline atolls is (Mueller-Dombois and Fosberg 1998). All of miniscule. Satawan Atoll in the Mortlock the atolls visited during this survey are in- Islands, southern Chuuk State, has the largest habited or (in the case of Ant Atoll) have been total land area, with 4.6 km2 distributed so in the recent past. Ornamental shrubs, among approximately 49 islets (Bryan 1971). trees, and herbs are common in the settle- Houk (¼ Pulusuk Atoll), a lone islet west of ments, which are usually located on one or Chuuk Lagoon, is the largest single island several of the larger islets; the others are vis- (2.8 km2) among all of these outlyers. Coco- ited frequently to harvest coconuts, crabs, and nut (Cocos nucifera) and breadfruit (Artocarpus other forest products used by the community. Butterflies of the Eastern Caroline Islands . Buden et al. 99 materials and methods record from Kosrae, but this sight record re- quires confirmation.] Butterflies were collected by D.W.B. when the opportunity arose during biological sur- veys of several different taxonomic groups, Family Lycaenidae including birds, reptiles, odonates, and milli- Catochrysops panormus (C. -

Mangroves Occurring on the Many Islands in the South Pacific Are Only a Small Component When Compared to the Worldwide Inventory of Mangroves

TECHNICAL ASSESSMENT AND SUPPORT FOR MANGROVE AND LITTORAL FOREST MANAGEMENT, PLANNING AND TRAINING FOR SMALL ISLANDS IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC Jan. 25, 2004 by James Denny Ward USDA Forest Service i FOREWORD Mangroves occurring on the many islands in the South Pacific are only a small component when compared to the worldwide inventory of mangroves. Although the mangroves found on the smaller islands may not seem as important on the global scale, they are extremely important to the small individual countries. Some of their benefits include shoreline protection, biodiversity, fisheries and a source for traditional products like building material, fuelwood and various cultural uses. These benefits are even more important to small island countries with limited resources and contributed to the survival of the indigenous people in earlier times. Realizing the importance of the mangrove resource the Forest & Trees Support Programme of SPC and the Heads of Forestry in the Pacific in cooperation with the USDA Forest Service conducted several missions during the last 10 years to assist the smaller island countries with preserving, protecting and managing their mangroves . The USDA Forest Service’s Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry based in Hawaii has been providing assistance to the Federated States of Micronesia and other islands with close ties to the United States for several years. Research conducted by this group has contributed greatly to the information base needed to manage mangroves throughout the South Pacific. This report is not all-inclusive but it is hoped that it will contain sufficient information to assist small islands in developing a management strategy for their individual countries. -

Reptiles, Birds, and Mammals of Pakin Atoll, Eastern Caroline Islands

Micronesica 29(1): 37-48 , 1996 Reptiles, Birds, and Mammals of Pakin Atoll, Eastern Caroline Islands DONALD W. BUDEN Division Mathematics of and Science, College of Micronesia, P. 0 . Box 159 Kolonia, Polmpei, Federated States of Micronesia 96941. Abstract-Fifteen species of reptiles, 18 birds, and five mammals are recorded from Pakin Atoll. None is endemic to Pakin and all of the residents tend to be widely distributed throughout Micronesia. Intro duced species include four mammals (Rattus exulans, Canis fami/iaris, Fe/is catus, Sus scrofa), the Red Junglefowl (Gallus gal/us) among birds, and at least one lizard (Varanus indicus). Of the 17 indigenous birds, ten are presumed or documented breeding residents, including four land birds, a heron, and five terns. The Micronesian Honeyeater (My=omela rubratra) is the most common land bird, followed closely by the Micro nesian Starling (Aplonis opaca). The vegetation is mainly Cocos forest, considerably modified by periodic cutting of the undergrowth, deliber ately set fires, and the rooting of pigs. Most of the present vertebrate species do not appear to be seriously endangered by present levels of human activity. But the Micronesian Pigeon (Ducula oceanica) is less numerous on the settled islands, probably reflecting increased hunting pressure, and sea turtles (especially Chelonia mydas) and their eggs are harvested indiscriminately . Introduction Terrestrial vertebrates have been poorly studied on many of the remote atolls of Micronesia, and distributional records are lacking or scanty for many islands. The present study documents the occurrence and relative abundance of reptiles, birds, and mammals on Pakin Atoll for the first time. -

Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008

OCHA Regional Office for Asia Pacific Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008 OCHA Presence in the Pacific Northern Papua New Guinea Fiji Mariana Humanitarian Affairs Unit (HAU), PNG Regional Disaster Response Islands (U.S.) UN House , Level 14, DeloitteTower, Advisor (RDRA), Fiji Douglas Street, PO Box 1041, 360 Victoria Parade, 3rd Floor Fiji +10 Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Development Bank Building, Suva, FIJI Tel: +675 321 2877 Tel: +679 331 6760, +679 331 6761 International Date Line Fax: +675 321 1224 Fax: +679 330 9762 Saipan Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Head: Vini Talai Head: Peter Muller Agana +12 Guam (U.S.) Pacific Ocean +10 MARSHALL ISLANDS Legend Depth (m) OCHA Presence Below 5,000 1,001 to 2,000 MICRONESIA (FSO) Koror Majuro Country capital Palikir 4,001 to 5,000 501 to 1,000 Territory capital PALAU +11 Illustrative boundary 3,001 to 4,000 101 to 500 +9 +10 Time difference with UTC 2,001 to 3,000 o to 100 Tarawa (New York: UTC -5 Equator NAURU Geneva: UTC +1) IMPORTANT NOTE: The boundaries on this map are for illustrative purposes only Yaren Naming Convention and were derived from the map ’The +12 +12 KIRIBATI UN MEMBER STATE Pacific Islands’ published in 2004 by the Territory or Associated State Secretariat of the Pacific Community. INDONESIA TUVALU -11 -10 PAPUA NEW GUINEA United Nations Office for the Coordination +10 +12 of Humanitarian affairs (OCHA) Funafuti Toke lau (N.Z.) Regional Office for Asia Pacific (ROAP) Honiara Executive Suite, 2nd Floor, -10 UNCC Building, -

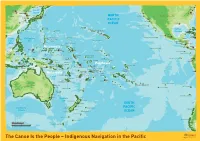

Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific

Hokkaido Vladivostok New York Philadelphia Beijing North Korea Sea of Tianjin Japan P'yongyang Sacramento Washington Seoul Japan Honshu NORTH San Francisco United States of America China South Tokyo Nagoya Korea Pusan Osaka Los Angeles PACIFIC Cheju-Do Shikoku San Diego Shanghai Kyushu OCEAN New Orleans Guadalupe Island (Mex.) Midway Baja Ryukyu Ogasawara- Islands (US) California Trench Okinawa-Jima (Jap.) Gunto (Jap.) Gulf of Miami Minami-Tori- Hawaiian Islands (US) Shima (Jap.) Mexico Havana Taiwan Kauai Cuba Oahu Mexico Hainan Dao Honolulu Guadalajara Jamaica Mariana Mexico Northern Wake Island (US) Hawaii Revillagigedo Island (Mex.) Kingston Philippine Ridge Belize South Luzon Mariana Islands Johnston Atoll (US) China Sea (US) Guatemala Honduras Manila Saipan Sea Guam (US) Marshall Islands El Salvador Nicaragua Philippines Enewetak Managua Costa Rica Panama Yap Islands Micronesia San José Palawan Ratak Clipperton Island (Fr.) Mindanao Pohnpei Chain Davao Melekeok Satawai Panama Chuuk Palikir Majuro Palmyra Atoll (US) Ralik Cocos Islands (CR) Brunei Palau Kosrae Chain Malaysia Line Malpelo Island (Col.) Federated States of Micronesia Gilbert Islands Howland Island (US) Islands Colombia Halmahera Kalimantan Tarawa Baker Island (US) Bismarck Archipelago Quito Jarvis Island (US) Galapagos Islands (Ec.) Sulawesi New Ireland Nauru Guayaquil Phoenix Islands Kiribati Malden Rabaul Ecuador Seram New Guinea Papua Bougainville Solomon Nanumea Vaiaku Indonesia New Guinea New Britain Santa Isabel Islands Polynesia Surabaya Funafuti Marquesas Islands -

Part I ABATAN WATERSHED CHARACTERIZATION REPORT

Part I [Type text] Page 0 Abatan Watershed Characterization Report and Integrated Watershed Management Plan September 2010 Part I ABATAN WATERSHED CHARACTERIZATION REPORT I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND INFORMATION The Abatan Watershed is the third largest of the 11 major watershed networks that support water needs and other requirements of the island province of Bohol. It covers some 38,628 hectares or close to 9% of the province‟s total land area. It has three distinct land divisions, coastal, lowland and upland. The coastal areas are marine and not along the most of the river. Table 1. Municipalities and their barangays comprising the Abatan Watershed Municipality Barangay Percent Angilan, Bantolinao, Bicahan, Bitaugan, Bungahan, Can-omay, Canlaas, 1. Antequera Cansibuan, Celing, Danao, Danicop, Mag-aso, Poblacion, Quinapon-an, 100 Santo Rosario, Tabuan, Tagubaas, Tupas, Ubojan, Viga, and Villa Aurora Baucan Norte, Baucan Sur, Boctol, Boyog Sur, Cabad, Candasig, Cantalid, Cantomimbo, Datag Norte, Datag Sur, Del Carmen Este, Del Carmen Norte, 2. Balilihan 71 Del Carmen Sur, Del Carmen Weste, Dorol, Haguilanan Grande, Magsija, Maslog, Sagasa, Sal-ing, San Isidro, and San Roque 3. Calape Cabayugan, Sampoangon, and Sohoton 9 Alegria, Ambuan, Bongbong, Candumayao, Causwagan, Haguilanan, 4. Catigbian Libertad Sur, Mantasida, Poblacion, Poblacion Weste, Rizal, and 54 Sinakayanan 5. Clarin Cabog, Danahao, and Tubod 12 Anislag, Canangca-an, Canapnapan, Cancatac, Pandol, Poblacion, and 6. Corella 88 Tanday Fatima, Loreto, Lourdes, Malayo Norte, Malayo Sur, Monserrat, New 7. Cortes Lourdes, Patrocinio, Poblacion, Rosario, Salvador, San Roque, and Upper de 93 la Paz 8. Loon Campatud 1 9. Maribojoc Agahay, Aliguay, Busao, Cabawan, Lincod, San Roque, and Toril 39 10. -

Western Ghats & Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile WESTERN GHATS & SRI LANKA BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT WESTERN GHATS REGION FINAL VERSION MAY 2007 Prepared by: Kamal S. Bawa, Arundhati Das and Jagdish Krishnaswamy (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology & the Environment - ATREE) K. Ullas Karanth, N. Samba Kumar and Madhu Rao (Wildlife Conservation Society) in collaboration with: Praveen Bhargav, Wildlife First K.N. Ganeshaiah, University of Agricultural Sciences Srinivas V., Foundation for Ecological Research, Advocacy and Learning incorporating contributions from: Narayani Barve, ATREE Sham Davande, ATREE Balanchandra Hegde, Sahyadri Wildlife and Forest Conservation Trust N.M. Ishwar, Wildlife Institute of India Zafar-ul Islam, Indian Bird Conservation Network Niren Jain, Kudremukh Wildlife Foundation Jayant Kulkarni, Envirosearch S. Lele, Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Environment & Development M.D. Madhusudan, Nature Conservation Foundation Nandita Mahadev, University of Agricultural Sciences Kiran M.C., ATREE Prachi Mehta, Envirosearch Divya Mudappa, Nature Conservation Foundation Seema Purshothaman, ATREE Roopali Raghavan, ATREE T. R. Shankar Raman, Nature Conservation Foundation Sharmishta Sarkar, ATREE Mohammed Irfan Ullah, ATREE and with the technical support of: Conservation International-Center for Applied Biodiversity Science Assisted by the following experts and contributors: Rauf Ali Gladwin Joseph Uma Shaanker Rene Borges R. Kannan B. Siddharthan Jake Brunner Ajith Kumar C.S. Silori ii Milind Bunyan M.S.R. Murthy Mewa Singh Ravi Chellam Venkat Narayana H. Sudarshan B.A. Daniel T.S. Nayar R. Sukumar Ranjit Daniels Rohan Pethiyagoda R. Vasudeva Soubadra Devy Narendra Prasad K. Vasudevan P. Dharma Rajan M.K. Prasad Muthu Velautham P.S. Easa Asad Rahmani Arun Venkatraman Madhav Gadgil S.N. Rai Siddharth Yadav T. Ganesh Pratim Roy Santosh George P.S. -

Solomon Islands B ! Fagani C D ! Waimapuru ! ! Solomon Sea Mainga Tawani Vanuatu ! ! Rennel Island Manakia

FRAME B 155°E 160°E Rorovana ! ! ! Torokina Panguna Karakun Koiaris ! ! Papua New Guin! ea Taki ! ! Jaba Sininai ! Pupuku PACIFIC OCEAN Aitara ! ! ! Kaekui Mission ! Birambira ! Tokuaka Susuka !Kombokisa !! Kutakana Lukuvaru Shortland Island PACIFIC OCEAN ! ! Ghaomai Choiseul Zambanarungga Shortland I ! ! Vure ! Trevanion Noka ! ! Mono I Matamotu ! ! ! Masoko Java Malemgeulu ! ! Paraso ! Zuzuao Santa Cruz Islands Apakhö ! ! ! Point Lunga ! Eleoteve Arambu Filuo Vana!! ! ! Litoghahira Sambora Santa Isabel Island FRAME D Kolomb!angara! Ganongga ! New Georgia Islands ! Tapurai Tuarugu ! Biluro ! ! Mburuku Loalonga ! Lokiha ! ! ! Sepi ! Ageraba Harai Mbareho ! Fokinkorra ! S o l o m o n I s l a n d s Auki Kunura ! ! Kwaimbaambaala ! Vura Nggaulai'ato'o ! ! ! Siota !! Manikiriu Tulagi Paunairo Vatupilei ! ! Palikir Abungari !. Koror !. Marshall Islands Malaita Palau Guranja Honiara Micronesia Hularu ! ! .! !Gembua ! Guadalcanal Rere ! Kiribati ! ! PACIFIC OCEAN Solomon Sea Mbaole ! Sitaronda Ahenawai Anoni'usu Nauru Ralavu Raurembo ! Mwarada ! ! ! Ione ! Lakatana ! Ahia I n d o n e s i a Makina 10°S Papua New 10°S Guinea Solomon Sea Honiara Heuru !. Port Moresby !. ! Etamarorai Solomon Islands B ! Fagani C D ! Waimapuru ! ! Solomon Sea Mainga Tawani Vanuatu ! ! Rennel Island Manakia !.Port-Vila ! San Cristobal Australia Vinegau ! New Caledonia Na Wosi ! Funakumwa ! ! !. Hauraha Nouméa FRAME A Napasiwai FRAME C 155°E 160°E Date Created: 04- JUL - 2011 Map Num: LogCluster_SLB_LCA_004 Kilometers .! National Capital Road Network National Boundary Coord.System/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 S O L O M O N GLIDE Num: ! Village (selection) Secondary Surface Waterbody The boundaries and names and the designations 0 50 100 150 200 used on this map do not imply official endorsement I S L A N D S FRAME A Nominal Scale 1:62,420,000 at A4 Tertiary or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Species Boundaries, Biogeography, and Intra-Archipelago Genetic Variation Within the Emoia Samoensis Species Group in the Vanuatu Archipelago and Oceania" (2008)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Species boundaries, biogeography, and intra- archipelago genetic variation within the Emoia samoensis species group in the Vanuatu Archipelago and Oceania Alison Madeline Hamilton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Hamilton, Alison Madeline, "Species boundaries, biogeography, and intra-archipelago genetic variation within the Emoia samoensis species group in the Vanuatu Archipelago and Oceania" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3940. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3940 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SPECIES BOUNDARIES, BIOGEOGRAPHY, AND INTRA-ARCHIPELAGO GENETIC VARIATION WITHIN THE EMOIA SAMOENSIS SPECIES GROUP IN THE VANUATU ARCHIPELAGO AND OCEANIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Alison M. Hamilton B.A., Simon’s Rock College of Bard, 1993 M.S., University of Florida, 2000 December 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my graduate advisor, Dr. Christopher C. Austin, for sharing his enthusiasm for reptile diversity in Oceania with me, and for encouraging me to pursue research in Vanuatu. His knowledge of the logistics of conducting research in the Pacific has been invaluable to me during this process. -

Micronesian Art Historical Research and Library Collection Resources in Micronesia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 377 132 SO 024 616 AUTHOR Haynes, Douglas TITLE Micronesian Art Historical Research and Library Collection Resources in Micronesia. PUB DATE Nov 91 NOTE 9p.; Paper presented to the Art Education Delegation Exchange (Beijing, China, November 1991). PUB TYPE Reference Materials General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Architecture; Archives; *Art History; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Library Collections; *Non Western Civilization IDENTIFIERS Micronesia ABSTRACT This paper briefly describes the geographic region and some indigenous artifacts of Micronesia. The state of art historical research in the area and currently available library resources are discussed. Micronesia is comprised of seven island nations peopled by distinctly unique cultural groups. Study of Micronesian art and architecture is relatively recent. Early work was done by German, then Japanese, expeditions. More recently, Americans, as well as European and Japanese researchers, have studied the art and cultures of Micronesia. Among art forms studied are latte stones, dating from 1000 A.D. to 1668 A.D. These were hand smoothed and fitted limestone columns and capstones used to construct A-frame houses for the Chamorros, a people of the Mariana Islands group. The bai, a communal village house of Palau, is decorated with sculpture:, expressing a complex iconography of mythological symbolism. Another architectural accomplishment of Micronesians are the stone cities of Pohnpei and Kosrae, dating from the 8th-9th centuries to 1830. The largest collection of Micronesian art history materials available in the islands is the collection at the University of Guam (Mangilao). Other collections are located in the Pal=su National Museum Library in Koror, Palau; the Community College of Micronesia Pacific Collection in Kolonia, Pohnpei; The Nieves Flores Public Library in Agana, Guam; and the Federated States of Micronesia National Archives in Palikir, Pohnpe. -

The Comparative Biogeography of Philippine Geckos Challenges Predictions from a Paradigm of Climate-Driven Vicariant Diversification Across an Island Archipelago

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/395434; this version posted April 16, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Running head: Comparative biogeography of Philippine geckos The comparative biogeography of Philippine geckos challenges predictions from a paradigm of climate-driven vicariant diversification across an island archipelago Jamie R. Oaks ∗1, Cameron D. Siler2, and Rafe M. Brown3 1Department of Biological Sciences & Museum of Natural History, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama 36849, USA 2Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History and Department of Biology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma 73072-7029 3Biodiversity Institute and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA April 16, 2019 Abstract A primary goal of biogeography is to understand how large-scale environmental pro- cesses, like climate change, affect diversification. One often-invoked but seldom tested process is the “species-pump” model, in which repeated bouts of co-speciation are driven by oscillating climate-induced habitat connectivity cycles. For example, over the past three million years, the landscape of the Philippine Islands has repeatedly coalesced and fragmented due to sea-level changes associated with glacial cycles. This repeated climate-driven vicariance has been proposed as a model of speciation across evolu- tionary lineages codistributed throughout the islands. This model predicts speciation times that are temporally clustered around the times when interglacial rises in sea level fragmented the islands. -

Genus Sphenomorphus): Three New Species from the Mountains of Luzon and Clarification of the Status of the Poorly Knowns

Scientific Papers Natural History Museum The University of Kansas 13 october 2010 number 42:1–27 Species boundaries in Philippine montane forest skinks (Genus Sphenomorphus): three new species from the mountains of Luzon and clarification of the status of the poorly knownS. beyeri, S. knollmanae, and S. laterimaculatus By RAFe.m..BROwN1,2,6,.CHARleS.w..lINkem1,.ARvIN.C..DIeSmOS2,.DANIlO.S..BAleTe3,.melIzAR.v..DUyA4,. AND.JOHN.w..FeRNeR5 1 Natural History Museum, Biodiversity Institute, and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, The University of Kansas, 1345 Jayhawk Boulevard, Lawrence, KS 66045-7561, U.S.A.; E-mail: (RMB) [email protected]; (CWL) [email protected] 2 Herpetology Section, Zoology Division, National Museum of the Philippines, Executive House, P. Burgos Street, Rizal Park, Metro Manila, Philippines; E-mail: (ACD) [email protected] 3 Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 S Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605; E-mail: [email protected] 4 Conservation International Philippines, No. 6 Maalalahanin Street, Teachers Village, Diliman 1101 Quezon City; Philippines. Cur- rent Address: 188 Francisco St., Guinhawa Subd., Malolos, Bulacan 3000 Philippines; E-mail: [email protected] 5 Department of Biology, Thomas More College, Crestview Hills, Kentucky, 41017, U.S.A.; E-mail: [email protected] 6 Corresponding author Contents ABSTRACT...............................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................2