Cultural and Socioeconomic Determinants of Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LD ANALYSIS of Inos Snps in an ISOLATED NORFOLK ISLAND

Linkage disequilibrium analysis in the genetically isolated Norfolk Island population Author Bellis, Claire, Cox, Hannah, Ovcaric, Micky, Begley, Kimberly, Lea, Rodney, Quinlan, Sharon, Burgner, D, Heath, SC, Blangero, J, Griffiths, Lyn Published 2008 Journal Title Heredity DOI https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6801083 Copyright Statement © 2008 Nature Publishing Group. This is the author-manuscript version of this paper. Reproduced in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/22878 Link to published version http://www.nature.com/hdy Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis in the Genetically Isolated Norfolk Island Population C. Bellis1, R.A Lea1,2, D. Burgner3, M. Ovcaric1, S.C Heath4, J. Blangero5 and L.R Griffiths1 1 Genomics Research Centre School of Medical Science Griffith University Gold Coast PMB 50, GCMC Bundall 9726. e-mail: [email protected] Tel.: +61 7 5552 8808, Fax: +61 7 5552 8908 2 Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd, School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand 3 School of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia 4 Centre National de Génotypage, 2 Rue Gaston Cremieux, Evry, France. 5 Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, San Antonio, Texas, USA Running title: Norfolk Island LD analysis Keywords: Norfolk Island, linkage disequilibrium, genetic isolate, iNOS, Xq13.3 Word count: 3544 Page 1 of 23 Norfolk Island LD analysis ABSTRACT Norfolk Island is a genetic isolate, possessing unique population characteristics that could be utilized for complex disease gene localization. -

The Archaeology of Lapita Dispersal in Oceania

The archaeology of Lapita dispersal in Oceania pers from the Fourth Lapita Conference, June 2000, Canberra, Australia / Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics, as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for Southeast Asia and blue for the Pacific islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers, and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: coastal sites in southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: archaeological excavations in the eastern central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: the geography and ecology of traffic in the interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: art and archeaology in the Laura area. -

Mangroves Occurring on the Many Islands in the South Pacific Are Only a Small Component When Compared to the Worldwide Inventory of Mangroves

TECHNICAL ASSESSMENT AND SUPPORT FOR MANGROVE AND LITTORAL FOREST MANAGEMENT, PLANNING AND TRAINING FOR SMALL ISLANDS IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC Jan. 25, 2004 by James Denny Ward USDA Forest Service i FOREWORD Mangroves occurring on the many islands in the South Pacific are only a small component when compared to the worldwide inventory of mangroves. Although the mangroves found on the smaller islands may not seem as important on the global scale, they are extremely important to the small individual countries. Some of their benefits include shoreline protection, biodiversity, fisheries and a source for traditional products like building material, fuelwood and various cultural uses. These benefits are even more important to small island countries with limited resources and contributed to the survival of the indigenous people in earlier times. Realizing the importance of the mangrove resource the Forest & Trees Support Programme of SPC and the Heads of Forestry in the Pacific in cooperation with the USDA Forest Service conducted several missions during the last 10 years to assist the smaller island countries with preserving, protecting and managing their mangroves . The USDA Forest Service’s Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry based in Hawaii has been providing assistance to the Federated States of Micronesia and other islands with close ties to the United States for several years. Research conducted by this group has contributed greatly to the information base needed to manage mangroves throughout the South Pacific. This report is not all-inclusive but it is hoped that it will contain sufficient information to assist small islands in developing a management strategy for their individual countries. -

Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008

OCHA Regional Office for Asia Pacific Pacific Island Countries and Territories Issued: 19 February 2008 OCHA Presence in the Pacific Northern Papua New Guinea Fiji Mariana Humanitarian Affairs Unit (HAU), PNG Regional Disaster Response Islands (U.S.) UN House , Level 14, DeloitteTower, Advisor (RDRA), Fiji Douglas Street, PO Box 1041, 360 Victoria Parade, 3rd Floor Fiji +10 Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Development Bank Building, Suva, FIJI Tel: +675 321 2877 Tel: +679 331 6760, +679 331 6761 International Date Line Fax: +675 321 1224 Fax: +679 330 9762 Saipan Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Head: Vini Talai Head: Peter Muller Agana +12 Guam (U.S.) Pacific Ocean +10 MARSHALL ISLANDS Legend Depth (m) OCHA Presence Below 5,000 1,001 to 2,000 MICRONESIA (FSO) Koror Majuro Country capital Palikir 4,001 to 5,000 501 to 1,000 Territory capital PALAU +11 Illustrative boundary 3,001 to 4,000 101 to 500 +9 +10 Time difference with UTC 2,001 to 3,000 o to 100 Tarawa (New York: UTC -5 Equator NAURU Geneva: UTC +1) IMPORTANT NOTE: The boundaries on this map are for illustrative purposes only Yaren Naming Convention and were derived from the map ’The +12 +12 KIRIBATI UN MEMBER STATE Pacific Islands’ published in 2004 by the Territory or Associated State Secretariat of the Pacific Community. INDONESIA TUVALU -11 -10 PAPUA NEW GUINEA United Nations Office for the Coordination +10 +12 of Humanitarian affairs (OCHA) Funafuti Toke lau (N.Z.) Regional Office for Asia Pacific (ROAP) Honiara Executive Suite, 2nd Floor, -10 UNCC Building, -

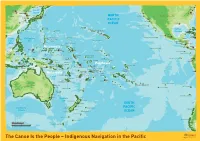

Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific

Hokkaido Vladivostok New York Philadelphia Beijing North Korea Sea of Tianjin Japan P'yongyang Sacramento Washington Seoul Japan Honshu NORTH San Francisco United States of America China South Tokyo Nagoya Korea Pusan Osaka Los Angeles PACIFIC Cheju-Do Shikoku San Diego Shanghai Kyushu OCEAN New Orleans Guadalupe Island (Mex.) Midway Baja Ryukyu Ogasawara- Islands (US) California Trench Okinawa-Jima (Jap.) Gunto (Jap.) Gulf of Miami Minami-Tori- Hawaiian Islands (US) Shima (Jap.) Mexico Havana Taiwan Kauai Cuba Oahu Mexico Hainan Dao Honolulu Guadalajara Jamaica Mariana Mexico Northern Wake Island (US) Hawaii Revillagigedo Island (Mex.) Kingston Philippine Ridge Belize South Luzon Mariana Islands Johnston Atoll (US) China Sea (US) Guatemala Honduras Manila Saipan Sea Guam (US) Marshall Islands El Salvador Nicaragua Philippines Enewetak Managua Costa Rica Panama Yap Islands Micronesia San José Palawan Ratak Clipperton Island (Fr.) Mindanao Pohnpei Chain Davao Melekeok Satawai Panama Chuuk Palikir Majuro Palmyra Atoll (US) Ralik Cocos Islands (CR) Brunei Palau Kosrae Chain Malaysia Line Malpelo Island (Col.) Federated States of Micronesia Gilbert Islands Howland Island (US) Islands Colombia Halmahera Kalimantan Tarawa Baker Island (US) Bismarck Archipelago Quito Jarvis Island (US) Galapagos Islands (Ec.) Sulawesi New Ireland Nauru Guayaquil Phoenix Islands Kiribati Malden Rabaul Ecuador Seram New Guinea Papua Bougainville Solomon Nanumea Vaiaku Indonesia New Guinea New Britain Santa Isabel Islands Polynesia Surabaya Funafuti Marquesas Islands -

Solomon Islands B ! Fagani C D ! Waimapuru ! ! Solomon Sea Mainga Tawani Vanuatu ! ! Rennel Island Manakia

FRAME B 155°E 160°E Rorovana ! ! ! Torokina Panguna Karakun Koiaris ! ! Papua New Guin! ea Taki ! ! Jaba Sininai ! Pupuku PACIFIC OCEAN Aitara ! ! ! Kaekui Mission ! Birambira ! Tokuaka Susuka !Kombokisa !! Kutakana Lukuvaru Shortland Island PACIFIC OCEAN ! ! Ghaomai Choiseul Zambanarungga Shortland I ! ! Vure ! Trevanion Noka ! ! Mono I Matamotu ! ! ! Masoko Java Malemgeulu ! ! Paraso ! Zuzuao Santa Cruz Islands Apakhö ! ! ! Point Lunga ! Eleoteve Arambu Filuo Vana!! ! ! Litoghahira Sambora Santa Isabel Island FRAME D Kolomb!angara! Ganongga ! New Georgia Islands ! Tapurai Tuarugu ! Biluro ! ! Mburuku Loalonga ! Lokiha ! ! ! Sepi ! Ageraba Harai Mbareho ! Fokinkorra ! S o l o m o n I s l a n d s Auki Kunura ! ! Kwaimbaambaala ! Vura Nggaulai'ato'o ! ! ! Siota !! Manikiriu Tulagi Paunairo Vatupilei ! ! Palikir Abungari !. Koror !. Marshall Islands Malaita Palau Guranja Honiara Micronesia Hularu ! ! .! !Gembua ! Guadalcanal Rere ! Kiribati ! ! PACIFIC OCEAN Solomon Sea Mbaole ! Sitaronda Ahenawai Anoni'usu Nauru Ralavu Raurembo ! Mwarada ! ! ! Ione ! Lakatana ! Ahia I n d o n e s i a Makina 10°S Papua New 10°S Guinea Solomon Sea Honiara Heuru !. Port Moresby !. ! Etamarorai Solomon Islands B ! Fagani C D ! Waimapuru ! ! Solomon Sea Mainga Tawani Vanuatu ! ! Rennel Island Manakia !.Port-Vila ! San Cristobal Australia Vinegau ! New Caledonia Na Wosi ! Funakumwa ! ! !. Hauraha Nouméa FRAME A Napasiwai FRAME C 155°E 160°E Date Created: 04- JUL - 2011 Map Num: LogCluster_SLB_LCA_004 Kilometers .! National Capital Road Network National Boundary Coord.System/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 S O L O M O N GLIDE Num: ! Village (selection) Secondary Surface Waterbody The boundaries and names and the designations 0 50 100 150 200 used on this map do not imply official endorsement I S L A N D S FRAME A Nominal Scale 1:62,420,000 at A4 Tertiary or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Micronesian Art Historical Research and Library Collection Resources in Micronesia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 377 132 SO 024 616 AUTHOR Haynes, Douglas TITLE Micronesian Art Historical Research and Library Collection Resources in Micronesia. PUB DATE Nov 91 NOTE 9p.; Paper presented to the Art Education Delegation Exchange (Beijing, China, November 1991). PUB TYPE Reference Materials General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Architecture; Archives; *Art History; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Library Collections; *Non Western Civilization IDENTIFIERS Micronesia ABSTRACT This paper briefly describes the geographic region and some indigenous artifacts of Micronesia. The state of art historical research in the area and currently available library resources are discussed. Micronesia is comprised of seven island nations peopled by distinctly unique cultural groups. Study of Micronesian art and architecture is relatively recent. Early work was done by German, then Japanese, expeditions. More recently, Americans, as well as European and Japanese researchers, have studied the art and cultures of Micronesia. Among art forms studied are latte stones, dating from 1000 A.D. to 1668 A.D. These were hand smoothed and fitted limestone columns and capstones used to construct A-frame houses for the Chamorros, a people of the Mariana Islands group. The bai, a communal village house of Palau, is decorated with sculpture:, expressing a complex iconography of mythological symbolism. Another architectural accomplishment of Micronesians are the stone cities of Pohnpei and Kosrae, dating from the 8th-9th centuries to 1830. The largest collection of Micronesian art history materials available in the islands is the collection at the University of Guam (Mangilao). Other collections are located in the Pal=su National Museum Library in Koror, Palau; the Community College of Micronesia Pacific Collection in Kolonia, Pohnpei; The Nieves Flores Public Library in Agana, Guam; and the Federated States of Micronesia National Archives in Palikir, Pohnpe. -

Norfolk Island Review of the Annual Reports of the Department of Transport and Regional Services and the Department of the Environment and Heritage

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Norfolk Island Review of the Annual Reports of the Department of Transport and Regional Services and the Department of the Environment and Heritage Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories July 2004 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2004 ISBN 0 642 78480 9 Contents Foreword................................................................................................................................................... vi 40th Parliament .......................................................................................................................................viii Membership of the Committee................................................................................................................viii Terms of reference................................................................................................................................... ix List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. x List of recommendations.......................................................................................................................... xi 1 Introduction............................................................................................................. 1 The Purpose of the Inquiry............................................................................................................1 The Role of the Committee............................................................................................................3 -

I Vol .6 No.I March 1991 Starters in Dot's Victorian 24 Hour Track Championship Held at Coburg on 23124Th February, 1991. Th

I Vol .6 No.I March 1991 � - fl· Starters in Dot's Victorian 24 Hour Track Championship held at Coburg on 23124th February, 1991. The race was won forthe secondtime by Bryan Smith with an excellent distance of 250.729km. AUSTRALIAN ULTRA RUNNERS' ASSOCIATION INC. (Incorporated in Victoria) Registered Office: 4 Victory Street, Mitcham, 3132. Australia. telephone: (03) 874-2501 CONTENTS EDITORIAL 3 ULTRA-RUNNERS' CALENDAR 4-7 NZ EVENTS 8 COMMITTEEREPORT 8 A URA CLOTHING order form 9 MEMBERSHIP RENEWAL RATES 10 AURAPUBLIC LIABILITY INSURANCE 10 AGM NOTICE 11 AURACO MMITTEELIST 12-13 NOTICE OF SPECIAL RESOLUTIONS FOR AGM. 14-19 AURNATHLETICS AUSTRALIA AFFILIATION 20 WESTFIELD APPEAL FOR HELPERS 20 ADVICE ON LAPSCORING 21 IAN HUTCHISON CARICATURE 22 LETTERSTO EDITOR 23-28 RACE REPORTS AND RESULTS Westfield Striders 24 Hour Track Race - NSW 29 Campbelltown Mall 24 Hour Track Race- NSW 30 Royal National Park Ultra- NSW 31-35 Rainbow Trail Run - Q'ld 36-41 Bruny Island Ultra marathon - Tas 41 The Brindabella Classic - ACT 42 Campbelltown Aust. Six Day Track Championship - NSW 43-49 Gibson Ranch Multi Day Classic - California 50-51 Bogong to Hotham Trail - Vic 51-53 CHASE Carnival 50 Mile Road Race - Vic 53 Mansfieldto Mt.Buller 50 km Road Race - Vic 54 -57 Wyong 24 Hour Race - NSW 58-59 Cradle Mountain Trail Run - Tas 60 -61 Victorian 24 Hour Track Championship - Coburg, Vic 62-63 IAU (InternationalAssoc. of Ultrarunners)not ice 45 RACE ADVERTISEMENTS Queensland Marathon & Road Runners Club Inc. Ultra Series 1991 64 VMC 50 Mile Track Race - Box Hill 65-67 Westfield Run 1991 67-70 South AustralianVeterans A.C. -

Our Sea of Islands Our Livelihoods Our Oceania

Status and potential of locally-managed marine areas in the South Pacific: meeting natureOur conservation Sea of and Islands sustainable livelihood targets throughOur wide-spread Livelihoods implementation of LMMAs Our Oceania Framework for a Pacific Oceanscape: a catalyst for implementation of ocean policy Cristelle Pratt and Hugh Govan November 2010 This document was compiled by Cristelle Pratt and Hugh Govan. Part Two of the document was also reviewed by Andrew Smith, Annie Wheeler, Anthony Talouli, Bernard O’Callaghan, Carole Martinez, Caroline Vieux, Catherine Siota, Colleen Corrigan, Coral Pasisi, David Sheppard, Etika Rupeni, Greg Sherley, Jackie Thomas, Jeff Kinch, Kosi Latu, Lindsay Chapman, Maxine Anjiga, Modi Pontio, Olivier Tyack, Padma Lal, Pam Seeto, Paul Anderson, Paul Lokani, Randy Thaman, Samasoni Sauni, Sandeep Singh, Scott Radway, Sue Taei, Tagaloa Cooper, and Taholo Kami at the 2nd Marine Sector Working Group Meeting held in Apia, Samoa, 5–7 April 2010. Photography © Stuart Chape TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE – Toward a Framework for a Pacific Oceanscape: A Policy Analysis 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Context and scope for a Pacific Oceanscape Framework 9 3.0 Instruments – our ocean policy environment 11 3.1 Pacific Plan and Pacific Forum Leaders communiqués 15 3.2 The Pacific Islands Regional Oceans Policy (PIROP) 18 3.3 Synergies with PIROP 18 3.3.1 Relevant international and regional instruments and arrangements 18 3.3.2 Relevant national and non-governmental initiatives 20 4.0 Institutional Framework for Pacific Islands -

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Economic Report October 2003 P ACIFIC OCEAN

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Economic Report October 2003 P ACIFIC OCEAN HAWAII •Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands/Saipan •Guam HAWAII Republic of Palau Kauai • Oahu Niihau Molokai Maui Lanai American Samoa • Kahoolawe Hawaii Locations (Maps not shown to scale.) BANK OF HAWAII BRANCHES ABOUT BANK OF HAWAII The Bank provides convenient & IN-STORE BRANCHES access to financial services through (as of December 31, 2002) Bank of Hawaii Corporation is a its network of branches, in-store regional financial services company branches and ATMs, and its 24- Hawaii 76 serving businesses, consumers and hour telephone and Internet governments in Hawaii, American banking services. American Samoa 3 Samoa and the West Pacific. The Commonwealth of company’s principal subsidiary, As a company, we are committed to Northern Mariana Bank of Hawaii, was founded in providing the highest level of Islands/Saipan 2 1897 and is the largest independent quality customer service. For more financial institution in Hawaii. information about Bank of Hawaii, Guam 9 please visit our website at Republic of Palau 1 Bank of Hawaii Corporation and its www.boh.com. subsidiaries offer a wide range of financial products and services, Total 91 including: deposit and lending services, investments, trust services, private banking, leasing, mortgage, insurance, cash management, employee benefits and retirement plan services. www.boh.com TO OUR READERS: We are pleased to present this 2003 edition of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) Economic Report under a regional research and study partnership between Bank of Hawaii and the East-West Center. CNMI is one of the West Pacific markets which Bank of Hawaii serves, and the Bank’s presence here goes back more than three decades. -

Pacific Island Populations

POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS / MID-YEAR POPULATION ESTIMATE / VITAL STATISTICS / POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS / ESTIMATION DE LA POPULATION EN CARACTÉRISTIQUES DE LA POPULATION STATISTIQUES VITALES CARACTÉRISTIQUES DE LA POPULATION MILIEU D’ANNÉE Crude Crude Crude Net Annual Estimated Average Land area Urban Dependency Teenage Fertility Population Average Birth Rate a Death Rate a Migration Growth Rate Annual Growth Rate b Median e Infant Mortality Rate COUNTRY/TERRITORY (km²) Last Density population at Annual Sex Ratio c Ratio Total Fertility Rate Rate f (15–19) COUNTRY/TERRITORY count at last Household (‰) (‰) Rate (‰) (%) (%) Age d (IMR, ‰) g Life Expectancy at Birth h population (persons/ last census (%) Intercensal (15–59) (TFR) 2 Size PAYS / TERRITOIRE Superficie census km ) Growth Rate 2020 2030 2050 PAYS / TERRITOIRE census Rapport de Rapport de Indice synthétique Fécondité des h (km²) Population Tx brut de Tx brut de Tx brut de Tx de Estimation du tx de c Âges f Tx de mortalité Espérance de vie à la naissance Taille a a b masculinité d e adolescentes Population Densité urbaine Tx annuel de natalité mortalité migration croissance croissance annuel médian dépendance de fécondité (ISF) infantile (TMI, ‰) g Dernier moyenne (15–19) au dernier (habitants/ au dernier croissance (‰) (‰) nette (‰) annuel (%) (%) (15–59) recensement des recensement km2) recensement intercensitaire TFR Year Year IMR Year Males Females Year ménages Total Total Total 2020 2020–30 2030–50 2020 % (%) ISF Année Année TMI Année Hommes Femmes Année MELANESIA 540,260