17 Tumors of the Soft Tissue of the Lower Extremity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hemangiosarcoma Philip J

Ettinger & Feldman – Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine Client Information Sheet Hemangiosarcoma Philip J. Bergman What is hemangiosarcoma? Hemangiosarcoma (HSA; angiosarcoma or malignant hemangioendothelioma) is an extremely aggressive tumor of blood vessel origin. Because blood vessels are present throughout the body, virtually any site in the body can have HSA. HSA occurs most frequently in dogs (approximately 2% of all tumors) and the most common site is the spleen. However, additional common sites include the heart, liver, muscle, lung skin, bones, kidney, brain, abdomen, and oral cavity. In three large canine splenic disease studies encompassing approximately 2000 dogs, a “rule of two thirds” was found suggesting that approximately two thirds of dogs with a splenic mass have a cancer (therefore one third are not malignant) and two thirds of the malignant tumors of the spleen are HSA. HSA is a disease generally of older dogs and cats with an average onset of 9 to 10 years; however, there are reports of extremely young dogs and cats with this disease (5 to 6 months to a few years of age). German shepherd dogs are most commonly diagnosed with HSA; however, other large breed dogs such as golden retrievers and Labrador retrievers may also be overrepresented. In cats, the most common breed is the domestic shorthair. The cause of HSA in dogs and cats is presently unknown. Exposures to toxins such as chemicals, insecticides, and radiation have been reported in humans to be associated with HSA. Ultraviolet light exposure from the sun may be a potential cause of HSA in dogs, as HSAs of the skin are commonly seen in dogs with light hair and poor pigmentation (e.g., Salukis, Whippets, and white Bulldogs). -

Soft Tissue Cytopathology: a Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD

4/1/2020 Soft Tissue Cytopathology: A Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD Department of Pathology University of Pittsburgh Medical Center [email protected] What does the clinician want to know? • Is the lesion of mesenchymal origin or not? • Is it begin or malignant? • If it is malignant: – Is it a small round cell tumor & if so what type? – Is this soft tissue neoplasm of low or high‐grade? Practical diagnostic categories used in soft tissue cytopathology 1 4/1/2020 Practical approach to interpret FNA of soft tissue lesions involves: 1. Predominant cell type present 2. Background pattern recognition Cell Type Stroma • Lipomatous • Myxoid • Spindle cells • Other • Giant cells • Round cells • Epithelioid • Pleomorphic Lipomatous Spindle cell Small round cell Fibrolipoma Leiomyosarcoma Ewing sarcoma Myxoid Epithelioid Pleomorphic Myxoid sarcoma Clear cell sarcoma Pleomorphic sarcoma 2 4/1/2020 CASE #1 • 45yr Man • Thigh mass (fatty) • CNB with TP (DQ stain) DQ Mag 20x ALT –Floret cells 3 4/1/2020 Adipocytic Lesions • Lipoma ‐ most common soft tissue neoplasm • Liposarcoma ‐ most common adult soft tissue sarcoma • Benign features: – Large, univacuolated adipocytes of uniform size – Small, bland nuclei without atypia • Malignant features: – Lipoblasts, pleomorphic giant cells or round cells – Vascular myxoid stroma • Pitfalls: Lipophages & pseudo‐lipoblasts • Fat easily destroyed (oil globules) & lost with preparation Lipoma & Variants . Angiolipoma (prominent vessels) . Myolipoma (smooth muscle) . Angiomyolipoma (vessels + smooth muscle) . Myelolipoma (hematopoietic elements) . Chondroid lipoma (chondromyxoid matrix) . Spindle cell lipoma (CD34+ spindle cells) . Pleomorphic lipoma . Intramuscular lipoma Lipoma 4 4/1/2020 Angiolipoma Myelolipoma Lipoblasts • Typically multivacuolated • Can be monovacuolated • Hyperchromatic nuclei • Irregular (scalloped) nuclei • Nucleoli not typically seen 5 4/1/2020 WD liposarcoma Layfield et al. -

The Use of High Tumescent Power Assisted Liposuction in the Treatment of Madelung’S Collar

Letter to the Editor The use of high tumescent power assisted liposuction in the treatment of Madelung’s collar Henryk Witmanowski1,2, Łukasz Banasiak1, Grzegorz Kierzynka1, Jarosław Markowicz1, Jerzy Kolasiński1, Katarzyna Błochowiak3, Paweł Szychta1,4 1Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Medical College in Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland 2Department of Physiology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland 3Department of the Oral Surgery, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland 4Department of Oncological Surgery and Breast Diseases, Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital-Research Institute, Lodz, Poland Adv Dermatol Allergol 2017; XXXIV (4): 366–371 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2017.69319 Mild symmetrical lipomatosis (plural symmetrical The disease most commonly takes a proximal form lipomatosis, multiple symmetric lipomatosis – MSL), which takes the following areas of the body with the fol- also known as Madelung’s disease or Launois-Bensaude lowing frequency: the genial area 92.3%, cervical region syndrome is a rare disease of unknown etiology, first de- 67.7%, shoulder region 54.8%, abdominal 45.2%, chest scribed by Brodie in 1846, Madelung in 1888, and Launois 41.9%, thigh and pelvic rim 32.3% [11, 12]. The periph- with Bensaude in 1898 [1–3]. eral type mainly locates on both sides at the level of the Madelung’s disease incidence is 1 : 250000 [4]. Mul- hands, feet and knees, this is definitely a rarer form of tiple symmetric lipomatosis occurs mainly in the inhabit- the disease. The mixed form is described very rarely. The ants of the Mediterranean area and Eastern Europe, in specified central type is also engaged primarily around males (male to female ratio is 20 : 1), aged 30–70 years, the lower torso, and intermediate parts of the legs. -

Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of Blood Vessels 16 F.Ramon

16_DeSchepper_Tumors_and 15.09.2005 13:27 Uhr Seite 263 Chapter Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of Blood Vessels 16 F.Ramon Contents 42]. There are two major classification schemes for vas- cular tumors. That of Enzinger et al. [12] relies on 16.1 Introduction . 263 pathological criteria and includes clinical and radiolog- 16.2 Definition and Classification . 264 ical features when appropriate. On the other hand, the 16.2.1 Benign Vascular Tumors . 264 classification of Mulliken and Glowacki [42] is based on 16.2.1.1 Classification of Mulliken . 264 endothelial growth characteristics and distinguishes 16.2.1.2 Classification of Enzinger . 264 16.2.1.3 WHO Classification . 265 hemangiomas from vascular malformations. The latter 16.2.2 Vascular Tumors of Borderline classification shows good correlation with the clinical or Intermediate Malignancy . 265 picture and imaging findings. 16.2.3 Malignant Vascular Tumors . 265 Hemangiomas are characterized by a phase of prolif- 16.2.4 Glomus Tumor . 266 eration and a stationary period, followed by involution. 16.2.5 Hemangiopericytoma . 266 Vascular malformations are no real tumors and can be 16.3 Incidence and Clinical Behavior . 266 divided into low- or high-flow lesions [65]. 16.3.1 Benign Vascular Tumors . 266 Cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions are usually 16.3.2 Angiomatous Syndromes . 267 easily diagnosed and present no significant diagnostic 16.3.3 Hemangioendothelioma . 267 problems. On the other hand, hemangiomas or vascular 16.3.4 Angiosarcomas . 268 16.3.5 Glomus Tumor . 268 malformations that arise in deep soft tissue must be dif- 16.3.6 Hemangiopericytoma . -

Understanding Your Pathology Report: Benign Breast Conditions

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Understanding Your Pathology Report: Benign Breast Conditions When your breast was biopsied, the samples taken were studied under the microscope by a specialized doctor with many years of training called a pathologist. The pathologist sends your doctor a report that gives a diagnosis for each sample taken. Information in this report will be used to help manage your care. The questions and answers that follow are meant to help you understand medical language you might find in the pathology report from a breast biopsy1, such as a needle biopsy or an excision biopsy. In a needle biopsy, a hollow needle is used to remove a sample of an abnormal area. An excision biopsy removes the entire abnormal area, often with some of the surrounding normal tissue. An excision biopsy is much like a type of breast-conserving surgery2 called a lumpectomy. What does it mean if my report uses any of the following terms: adenosis, sclerosing adenosis, apocrine metaplasia, cysts, columnar cell change, columnar cell hyperplasia, collagenous spherulosis, duct ectasia, columnar alteration with prominent apical snouts and secretions (CAPSS), papillomatosis, or fibrocystic changes? All of these are terms that describe benign (non-cancerous) changes that the pathologist might see under the microscope. They do not need to be treated. They are of no concern when found along with cancer. More information about many of these can be found in Non-Cancerous Breast Conditions3. What does it mean if my report says fat necrosis? Fat necrosis is a benign condition that is not linked to cancer risk. -

Cutaneous Angiosarcoma: Report of Three Different and Typical Cases Admitted in a Unique Dermatology Clinic*

CASE REPORT 235 s Cutaneous angiosarcoma: report of three different and typical cases admitted in a unique dermatology clinic* Aline Neves Freitas Cabral1 Rafael Henrique Rocha1 Ana Cristina Vervloet do Amaral1 Karina Bittencourt Medeiros2 Paulo Sérgio Emerich Nogueira1 Lucia Martins Diniz3 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175326 Abstract: Angiosarcoma is a rare and aggressive tumor with high rates of metastasis and relapse. It shows a particular predi- lection for the skin and superficial soft tissues. We report three distinct and typical cases of angiosarcoma that were diagnosed in a single dermatology clinic over the course of less than a year: i) Angiosarcoma in lower limb affected by chronic lymph- edema, featuring Stewart-Treves syndrome; ii) a case of the most common type of angiosarcoma loated in the scalp and face of elderly man and; iii) a skin Angiosarcoma in previously irradiated breast. All lesions presented characteristic histopathological findings: irregular vascular proliferation that dissects the collagen bundles with atypical endothelial nuclei projection toward the lumen. Keywords: Hemangiosarcoma; Lymphangiosarcoma; Lymphedema; Non-Filarial Lymphedema; Sarcoma INTRODUCTION Angiosarcoma (AS) is a rare and aggressive neoplasm, that fibers, formed by endothelium with atypical nuclei, prominent to- originates from endothelial cells of lymphatic and blood vessels. It ac- ward the lumen; The tumoral lesion exhibited cohesive epithelioid counts for 5% of malignant skin tumors and less than 1% of all sarco- masses of atypical, large, rounded cells with acidophilic cytoplasm mas. It is notable for having a predilection for the skin and superficial and frequent mitotic figures. (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical anal- soft tissues. -

The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors In

Cancers 2020, 12 S1 of S7 Supplementary Materials The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors in Germany—Cross-Sectional Results of A Nationwide Observational Study (PROSa) Martin Eichler, Leopold Hentschel, Stephan Richter, Peter Hohenberger, Bernd Kasper, Dimosthenis Andreou, Daniel Pink, Jens Jakob, Susanne Singer, Robert Grützmann, Stephen Fung, Eva Wardelmann, Karin Arndt, Vitali Heidt, Christine Hofbauer, Marius Fried, Verena I. Gaidzik, Karl Verpoort, Marit Ahrens, Jürgen Weitz, Klaus-Dieter Schaser, Martin Bornhäuser, Jochen Schmitt, Markus K. Schuler and the PROSa study group Includes Entities We included sarcomas according to the following WHO classification. - Fletcher CDM, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. 468 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Kurman RJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, editors. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. 307 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016 Jul;70(1):106–19. - World Health Organization, Swerdlow SH, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: [... reflects the views of a working group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, October 25 - 27, 2007]. 4. ed. -

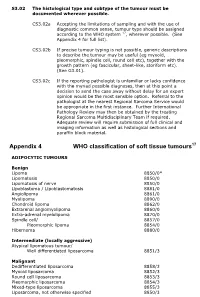

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours17

S3.02 The histological type and subtype of the tumour must be documented wherever possible. CS3.02a Accepting the limitations of sampling and with the use of diagnostic common sense, tumour type should be assigned according to the WHO system 17, wherever possible. (See Appendix 4 for full list). CS3.02b If precise tumour typing is not possible, generic descriptions to describe the tumour may be useful (eg myxoid, pleomorphic, spindle cell, round cell etc), together with the growth pattern (eg fascicular, sheet-like, storiform etc). (See G3.01). CS3.02c If the reporting pathologist is unfamiliar or lacks confidence with the myriad possible diagnoses, then at this point a decision to send the case away without delay for an expert opinion would be the most sensible option. Referral to the pathologist at the nearest Regional Sarcoma Service would be appropriate in the first instance. Further International Pathology Review may then be obtained by the treating Regional Sarcoma Multidisciplinary Team if required. Adequate review will require submission of full clinical and imaging information as well as histological sections and paraffin block material. Appendix 4 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours17 ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS Benign Lipoma 8850/0* Lipomatosis 8850/0 Lipomatosis of nerve 8850/0 Lipoblastoma / Lipoblastomatosis 8881/0 Angiolipoma 8861/0 Myolipoma 8890/0 Chondroid lipoma 8862/0 Extrarenal angiomyolipoma 8860/0 Extra-adrenal myelolipoma 8870/0 Spindle cell/ 8857/0 Pleomorphic lipoma 8854/0 Hibernoma 8880/0 Intermediate (locally -

Glomus Tumor in the Floor of the Mouth: a Case Report and Review of the Literature Haixiao Zou1,2, Li Song1, Mengqi Jia2,3, Li Wang4 and Yanfang Sun2,3*

Zou et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2018) 16:201 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1503-6 CASEREPORT Open Access Glomus tumor in the floor of the mouth: a case report and review of the literature Haixiao Zou1,2, Li Song1, Mengqi Jia2,3, Li Wang4 and Yanfang Sun2,3* Abstract Background: Glomus tumors are rare benign neoplasms that usually occur in the upper and lower extremities. Oral cavity involvement is exceptionally rare, with only a few cases reported to date. Case presentation: A 24-year-old woman with complaints of swelling in the left floor of her mouth for 6 months was referred to our institution. Her swallowing function was slightly affected; however, she did not have pain or tongue paralysis. Enhanced computed tomography revealed a 2.8 × 1.8 × 2.1 cm-sized well-defined, solid, heterogeneous nodule above the mylohyoid muscle. The mandible appeared to be uninvolved. The patient underwent surgery via an intraoral approach; histopathological examination revealed a glomus tumor. The patient has had no evidence of recurrence over 4 years of follow-up. Conclusions: Glomus tumors should be considered when patients present with painless nodules in the floor of the mouth. Keywords: Glomus tumor, Floor of mouth, Oral surgery Background Case presentation Theglomusbodyisaspecialarteriovenousanasto- A 24-year-old woman with a 6-month history of swelling mosisandfunctionsinthermalregulation.Glomustu- in the left floor of her mouth was referred to our institu- mors are rare, benign, mesenchymal tumors that tion. Although she experienced slight difficulty in swal- originate from modified smooth muscle cells of the lowing, she did not experience pain or tongue paralysis. -

The Role of Cytogenetics and Molecular Diagnostics in the Diagnosis of Soft-Tissue Tumors Julia a Bridge

Modern Pathology (2014) 27, S80–S97 S80 & 2014 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/14 $32.00 The role of cytogenetics and molecular diagnostics in the diagnosis of soft-tissue tumors Julia A Bridge Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA Soft-tissue sarcomas are rare, comprising o1% of all cancer diagnoses. Yet the diversity of histological subtypes is impressive with 4100 benign and malignant soft-tissue tumor entities defined. Not infrequently, these neoplasms exhibit overlapping clinicopathologic features posing significant challenges in rendering a definitive diagnosis and optimal therapy. Advances in cytogenetic and molecular science have led to the discovery of genetic events in soft- tissue tumors that have not only enriched our understanding of the underlying biology of these neoplasms but have also proven to be powerful diagnostic adjuncts and/or indicators of molecular targeted therapy. In particular, many soft-tissue tumors are characterized by recurrent chromosomal rearrangements that produce specific gene fusions. For pathologists, identification of these fusions as well as other characteristic mutational alterations aids in precise subclassification. This review will address known recurrent or tumor-specific genetic events in soft-tissue tumors and discuss the molecular approaches commonly used in clinical practice to identify them. Emphasis is placed on the role of molecular pathology in the management of soft-tissue tumors. Familiarity with these genetic events -

Case Reports Article – Rapidly Growing Mass in the Ear Canal: A

Arepen et al. (2020): Rapidly growing mass in the ear canal May 2020 Vol. 23 Issue 8 Case reports article – Rapidly growing mass in the ear canal: A rare case of isolated superficial angiomyxoma Siti Asmat Md Arepen1,2, Nor Eyzawiah Hassan1,2, Azlina Abd Rani1, Shahrul Hitam2 Mohd Khairi Md Daud3 1Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences,Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia. 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, Hospital Ampang, Selangor, Malaysia. 3Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Kelantan, Malaysia. Corresponding author: Nor Eyzawiah Hassan ([email protected]) Abstract: Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare benign skin tumour and usually present as an asymptomatic lesion. It is known to be highly recurrent and complete wide excision is the best treatment. This cace reported of 56 yr old gentleman presented with fleshy, pink coloured right external auditory mass. The mass arisen from the posterior wall of the canal at the bony–cartilaginous junction. Clinical diagnosis of an anaural polyp was made and the mass was excised. However, it rapidly recurred bigger than its actual size within a week. The histopathological examination was reported as superficial angiomyxoma. A differential diagnosis of isolated superficial angiomyxoma should be considered in the case of external auditory canal mass and Carney complex needs to be considered. Complete excision and regular follow up is recommended. Keywords: Benign tumour, external auditory canal, myxoma How to cite this article: How to cite this article: Arepen et al. (2020): Case reports article – Rapidly growing mass in the ear canal: A rare case of isolated superficial angiomyxoma, Ann Trop & Public Health, 23 (S8): 1279–1282. -

Dermatopathology

Dermatopathology Clay Cockerell • Martin C. Mihm Jr. • Brian J. Hall Cary Chisholm • Chad Jessup • Margaret Merola With contributions from: Jerad M. Gardner • Talley Whang Dermatopathology Clinicopathological Correlations Clay Cockerell Cary Chisholm Department of Dermatology Department of Pathology and Dermatopathology University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Central Texas Pathology Laboratory Dallas , TX Waco , TX USA USA Martin C. Mihm Jr. Chad Jessup Department of Dermatology Department of Dermatology Brigham and Women’s Hospital Tufts Medical Center Boston , MA Boston , MA USA USA Brian J. Hall Margaret Merola Department of Dermatology Department of Pathology University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Brigham and Women’s Hospital Dallas , TX Boston , MA USA USA With contributions from: Jerad M. Gardner Talley Whang Department of Pathology and Dermatology Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Boston, MA Little Rock, AR USA USA ISBN 978-1-4471-5447-1 ISBN 978-1-4471-5448-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4471-5448-8 Springer London Heidelberg New York Dordrecht Library of Congress Control Number: 2013956345 © Springer-Verlag London 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work.