Finding Gems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palomar Gem & Mineral Club Newsletter

Palomar Gem & Mineral Club Newsletter August 2016 Volume 57 Issue 07 PGMC Annual Picnic We had our annual summer picnic last month at Jesmond Dene Park. As always Moni did a fine job of coordinating the event which included great food brought by everyone as well as a good time of comparing the fine rocks and gems we have found. We had a great slab swap between our members and everyone seemed to have a good time. As summer ends and we get ready to ramp up again, we hope everyone had a safe and productive summer. August is usually a down month for PGMC so that any specialty classes can take place at the shop and folks can go on vacation. We look forward to seeing everyone at the September meeting. Check out the rest of the newsletter for more information about September’s meeting as well as upcoming class schedules. We begin classes this week! 1 Textured Metal Class Come and join in the fun, learning to texture metal and make one-of-kind earrings (3 to 4 pairs) or a bracelet). They are great gifts. You may also learn how to make your own ear wires. Instructors: Diane Hall & Annie Heffner Location: Club Shop Dates: November 20, 2016 Time: 10am-4pm Fee: $35 plus supply cost (club membership required - $25 fee for single membership). You will need about 1 ounce of silver or copper sheet, which we will purchase for every one who is signed up by November 11th. Sign ups after that will need to provide their own material. -

The Wittelsbach-Graff and Hope Diamonds: Not Cut from the Same Rough

THE WITTELSBACH-GRAFF AND HOPE DIAMONDS: NOT CUT FROM THE SAME ROUGH Eloïse Gaillou, Wuyi Wang, Jeffrey E. Post, John M. King, James E. Butler, Alan T. Collins, and Thomas M. Moses Two historic blue diamonds, the Hope and the Wittelsbach-Graff, appeared together for the first time at the Smithsonian Institution in 2010. Both diamonds were apparently purchased in India in the 17th century and later belonged to European royalty. In addition to the parallels in their histo- ries, their comparable color and bright, long-lasting orange-red phosphorescence have led to speculation that these two diamonds might have come from the same piece of rough. Although the diamonds are similar spectroscopically, their dislocation patterns observed with the DiamondView differ in scale and texture, and they do not show the same internal strain features. The results indicate that the two diamonds did not originate from the same crystal, though they likely experienced similar geologic histories. he earliest records of the famous Hope and Adornment (Toison d’Or de la Parure de Couleur) in Wittelsbach-Graff diamonds (figure 1) show 1749, but was stolen in 1792 during the French T them in the possession of prominent Revolution. Twenty years later, a 45.52 ct blue dia- European royal families in the mid-17th century. mond appeared for sale in London and eventually They were undoubtedly mined in India, the world’s became part of the collection of Henry Philip Hope. only commercial source of diamonds at that time. Recent computer modeling studies have established The original ancestor of the Hope diamond was that the Hope diamond was cut from the French an approximately 115 ct stone (the Tavernier Blue) Blue, presumably to disguise its identity after the that Jean-Baptiste Tavernier sold to Louis XIV of theft (Attaway, 2005; Farges et al., 2009; Sucher et France in 1668. -

A Survey of the Gemstone Resources of China

A SURVEY OF THE GEMSTONE RESOURCES OF CHINA By Peter C. Keller and Wang Fuquan The People's Republic of China has recently hina has historically been a land of great mystery, placed a high priority on identifying and C with natural resources and cultural treasures that, developing its gemstone resources. Initial until recently, were almost entirely hidden from the out- exploration by teams of geologists side world. From the point of view of the geologist and throughout China has identified many gemologist, one could only look at known geological maps deposits with significant potential, of this huge country and speculate on the potential impact including amher, cinnabar, garnets, blue sapphires, and diamonds. Small amounts of China would have on the world's gem markets if its gem ruby have' qlso been found. Major deposits resources were ever developed to their full potential. of nephriteyade as well as large numbers of During the past few years, the government of the Peo- gem-bearing pegmatite dilces have been ple's Republic of China (P.R.C.)has opened its doors to the identified.Significant deposits of peridot outside world in a quest for information and a desire for are crirrently being exploited from Hebei scientific and cultural cooperation. It was in this spirit of Province. Lastly, turqrloise rivaling the cooperation that a week-long series of lectures on gem- finest Persian material has been found in stones and their origins was presented by the senior author large quantities in Hubei and Shaanxi and a colleague to over 100 geologists from all over China Provinces. -

Spring 1995 Gems & Gemology

TABLE CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES 2 Rubies from Mong Hsu Adolf Pelsetti, I(ar7 Schmetzer, Heinz-Jiirgen Bernhardt, and Fred Mouawad " 28 The Yogo Sapphire Deposit Keith A. ~~chaluk NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 42 Meerschaum from Eskisehir Province, Turkey I<adir Sariiz and Islcender Isilc REGULAR FEATURES 52 Gem Trade Lab Notes Gem News Most Valuable Article Award Gems ed Gemology Challenge Book Reviews Gemological Abstracts Guidelines for Authors ABOUT THE COVER: One of the most important ruby localities of the 1990s cov- ers a broad orea near the town of Mong Hsu, in northeastern Myann~ar(B~lrrna). The distinctive gemological features of these rubies are detailed in this issue's lead article. The suite of fine jewelry illustraled here contains 36 Mong Hsu rubies with a total weigh1 of 65.90 ct; the two rubies in the ring total 5.23 ct. jewelry courtesy of Mouawad jewellers. Photo by Opass Sultsumboon-Opass Suksuniboon Studio, Bangltolz, Thailand. Typesetting for Gerrls eS Gemology is by Graphix Express, Santa Monica, CA. Color separations are by Effective Graphics, Compton, CA. Printing is by Cadmus lournal Services, Easton, MD. 0 1995 Gemological Institute of America All rights reserved ISSN 0016-626X - Editor-in-Chief Editor Editors, Gem Trade Lab Notes Richard T. Lidtlicoat Alicc S. I<cller Robcrt C. I<ammerling 1660 Stewart St. C. W. Fryer Associate Editors Smta Mon~ca,CA 90404 William E. Boyajian Editors, Gem News (800)421-7250 ~251 Robcrt C. Kamn~erling Rohcrt C. I<ammerling e-mail: altellcrBclass.org D. Vincent Manson John I. Koivula John Sinltanltas Sr~bscriptions Enirnanuel Fritsch Jln Ll~n Editors, Book llevielvs Technical Editor (800) 421-7250 x201 Susan B. -

Gemstones by Donald W

GEMSTONES By Donald W. olson Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Nicholas A. Muniz, statistical assistant, and the world production table was prepared by Glenn J. Wallace, international data coordinator. In this report, the terms “gem” and “gemstone” mean any gemstones and on the cutting and polishing of large diamond mineral or organic material (such as amber, pearl, petrified wood, stones. Industry employment is estimated to range from 1,000 to and shell) used for personal adornment, display, or object of art ,500 workers (U.S. International Trade Commission, 1997, p. 1). because it possesses beauty, durability, and rarity. Of more than Most natural gemstone producers in the United states 4,000 mineral species, only about 100 possess all these attributes and are small businesses that are widely dispersed and operate are considered to be gemstones. Silicates other than quartz are the independently. the small producers probably have an average largest group of gemstones; oxides and quartz are the second largest of less than three employees, including those who only work (table 1). Gemstones are subdivided into diamond and colored part time. the number of gemstone mines operating from gemstones, which in this report designates all natural nondiamond year to year fluctuates because the uncertainty associated with gems. In addition, laboratory-created gemstones, cultured pearls, the discovery and marketing of gem-quality minerals makes and gemstone simulants are discussed but are treated separately it difficult to obtain financing for developing and sustaining from natural gemstones (table 2). Trade data in this report are economically viable deposits (U.S. -

PERIDOT from TANZANIA by Carol M

PERIDOT FROM TANZANIA By Carol M. Stockton and D. Vincent Manson Peridot from a new locality, Tanzania, is described Duplex I1 refractometer and sodium light, approx- and compared with 13 other peridots from various imate a = 1.650, B = 1.658, and -y = 1.684, indi- localities in terms of color and chemical com- cating a biaxial positive optic character. The position. The Tanzanian specimen is lower in iron specific gravity, measured hydrostatically, is ap- content than all but the Norwegian peridots and is proximately 3.25. very similar to material from Zabargad, Egypt. A gem-quality enstatite that came from the same area CHEMISTRY in East Africa and with which Tanzanian peridot has been confused is also described. The Tanzanian peridot was analyzed using a MAC electron microprobe at an operating voltage of 15 KeV and beam current of 0.05 PA. The standards used were periclase for MgO, kyanite for Ala, quartz for SiOz, wollastonite for CaO, rutile for In September 1982, Dr. Horst Krupp, of Idar- TiOa, chromic oxide for CraOg, almandine-spes- Oberstein, sent GIA's Department of Research a sartine garnet for MnO, fayalite for FeO, and nickel sample of peridot for study. The stone was from oxide for NiO. The data were corrected using the a parcel that supposedly contained enstatite pur- Ultimate correction program (Chodos et al., 1973). chased from the Tanzanian State Gem Corpora- For purposes of comparison, we also selected tion, the source of a previous lot of enstatite that and analyzed peridots from major known locali- Dr. Krupp had already cut and marketed. -

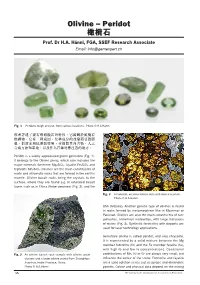

Olivine – Peridot 橄欖石 Prof

Olivine – Peridot 橄欖石 Prof. Dr H.A. Hänni, FGA, SSEF Research Associate Email: [email protected] Fig. 1 Peridots rough and cut, from various locations. Photo © H.A.Hänni 作者述了寶石級橄欖石的特性,它歸屬於橄欖石 類礦物,它有三種成因,化學成的改變而引致顏 色、折射率和比重的變異,並簡報其內含物、人工 合成方法和產地,以及作為首飾時應注意的地方。 Peridot is a widely appreciated green gemstone (Fig. 1). It belongs to the Olivine group, which also includes the major minerals forsterite Mg2SiO4, fayalite Fe2SiO4 and tephroite Mn2SiO4. Olivines are the main constituents of maic and ultramaic rocks that are formed in the earth’s mantle. Olivine-basalt rocks bring the crystals to the surface, where they are found e.g. in extended basalt layers such as in China (Hebei province) (Fig. 2), and the Fig. 3 A Pallasite, an iron-nickel matrix with olivine crystals. Photo © H.A.Hänni USA (Arizona). Another genetic type of olivines is found in rocks formed by metamorphism like in Myanmar or Pakistan. Olivines are also the main constituents of rare pallasites, nickel-iron meteorites, with large inclusions of olivine (Fig. 3). Synthetic forsterites with dopants are used for laser technology applications. Gemstone olivine is called peridot, and also chrysolite. It is represented by a solid mixture between the Mg member forsterite (fo) and the Fe member fayalite (fa), with high fo and low fa concentrations. Occasional Fig. 2 An olivine-basalt rock sample with olivine grain contributions of Mn, Ni or Cr are always very small, but clusters and a larger olivine crystal from Zhangjikou- inluence the colour of the stone. Forsterite and fayalite Xuanhua, Hebei Province, China. are a solid solution series just as pyrope and almandine Photo © H.A.Hänni garnets. -

Steven Universe Spinoff

Lapis and Peridot Episode 1: Homeworld Pumpkin Gabriella Scholl Steven Universe EXT. LAPIS AND PERIDOT'S BARN - DAY PERIDOT, a crystal gem who's short and green with a triangle shaped hairstyle, is lounging on a beach chair next to their man-made pond playing a game on her tablet. She loses the game, and she stands up and throws her tablet in frustration. PERIDOT Aarrghh! Peridot sits back down on the beach chair. After a moment Peridot gets up and gets her tablet. She returns to the chair and continues to play on her tablet. EXT. TRUCK BALCONY - DAY LAPIS, a crystal gem who's taller and blue; she has a short blue bob, is sitting in the bed of the truck and watching tv. Peridot stands beneath the bed of the truck looking up at Lapis. PERIDOT LAPIS! Lapis ignores Peridot's yelling and continues watching tv. PERIDOT LAPIS! Lapis continues to ignore Peridot. PERIDOT LAAAPIIIIS! Lapis rolls her eyes and begins to get up. Just as she's about to stand up Peridot flies up right in front of her on the lid of a garbage can. Lapis falls back down onto the bed of the truck. PERIDOT Lapis! LAPIS Peridot, you scared me. Peridot gets off of the trash can lid and sits it to the side. She sits directly in front of the tv. Lapis attempts to look around her to see the tv. Created using Celtx 2. PERIDOT Lapis, I'm bored. LAPIS So, go play on your tablet. PERIDOT That's what I've been doing. -

Peridot – the August Birthstone

Learning Series: Birthstones – August Peridot – The August Birthstone Background Peridot (pronounced pair-a-doe) is the gem variety of olivine and has the distinction of being the only gemstone found in meteorites and one of the few gemstones that occur in only one color; basically an olive green. Olivine, which is actually not an official mineral, is composed of two minerals: the iron-rich fayalite and the magnesium-rich forsterite. Of the two, peridot is usually closer to forsterite in composition although iron is the coloring agent for peridot. Unlike other gems that gain their color from impurities in their composition, the green of peridot is an intrinsic part of its nature. This makes it an idiochromatic stone – colored by itself. There are three prevailing theories as to how it got its name. In the gemstone trade it is called “peridot”, derived from the Greek word “peridona”, which means “to give richness”. Others feel it comes from the Arabic word faridat, which means “gem”. Still others claim it is derived from the French word peritot which means “unclear”. In either case, the French were supposedly the first to call it “peridot” in the 18th century. These August gemstones are found in volcanic basalts where they are formed deep within the earth under tremendous heat and pressure, and more unusually, in iron-nickel meteorites called pallasites. Peridot may have small inclusions of biotite (brown), chromite (black), pyrope garnet (dark red), spinel (tiny octahedra) or liquid and gas-filled inclusions that resemble fried eggs. An interesting gemological feature of some peridot is its most famous inclusion, called a “lily pad”. -

Gulfport Gems

Est. 1979 Harrison County Gem & Mineral Society, Inc. Gulfport Gems Volume 40 September 2019 Number 9 Member of the American & Southeast Federation of Mineralogical Society P.O. Box 10136 www.facebook.com/gulfportgems Gulfport, Ms. 39505 Website: www.gulfportgems.org A message from the President. Notes from the editor . Nominating Committee Dear Members, Volunteers are needed to serve on the Nominating Committee to get candidates for Monica, Charlene and I are leaving on Sep- our board next year. tember first to go to William Holland for the week. For those of you that have been, you Please step up to this challenge. know what a wonderful experience it is. For Present Slate: October Election: November those of you that have not been, try it at least Sworn In: December Take Office: January once. It is truly worth your time. 49th Annual New Orleans Gem, I hope to have lots of new things to show at Mineral, Fossil & Jewelry Show the meeting. So far, I have not been disap- pointed. October 11th, 12th, & 13th Look forward to seeing everyone in a few Alario Center weeks. 2000 Segnette Blvd. Westwego, La. 70094 Sue West, President 10 am - 6 pm Fri & Sat 10 am - 4 pm Sunday Rocks, gems, minerals, and jewelry Displays Demonstrations Raffle Board Meeting Door prizes Gulfport Library - Old Hwy. 49 Shop for the holidays! Next Meeting will be in October See page 15 “”Shows & Events” for more details Gulfport Gems Vol. 40 Number 9 1 September 2019 Harrison County Gem & Mineral Society Harrison County Gem & Mineral Society Webpage and Editor. -

Early Diamond Jewelry See Inside Cover

ti'1 ;i' .{"n b"' HH :U 3 c-r 6E au) -:L _lH brD [! - eF o 3 Itr-| i:j,::]': O .a E cl!+ r-Ri =r l\+ - x':a @ o \<[SFs-X : R 9€ 9.!-o I* & = t t-Y ry ,;;4 fr o a ts(\ 3 tug -::- ^ ,9 QJH 7.oa : l-] X 'rr l]i @ ex b :<; i-o ld o o-! :. i (n z )@N -.; :!t Fml \"-DF i :\ =orD =\ ^:a -nft< oSr-n ppr= HDV '- s\C r 6- "?tJz* Jlt : ni . s' o c'l.!..4< F' ryl - i o5 F ; {: Ll-l> Fr \ ='/E<- a5. {E j*yt p.y. .o n O S_ sr = = i o - ;iar x'i@ xo ia\=i, -G; t- z i i *O ^ > :.r - : ' - , i--! i---:= -i -z-- l:-\i i- t-3 j'-a : =: S ---i--.-- a- F == :\- O z O - -- - a s =. e ?.a !':ii1 : = - / - . :: i *a !- z : C CI =2 7 \- ^ t =r- l! t! lv- Iv -5 ":. -_r ! c\ co =- \] N TJ ?ti:iE€ i; 5j:; LLI ;;tttE3 E;Ei!iiii'E ri l.T-1 j F-{ i aEE g;iij 1=,iE 3iE;i; ; a;E{ i ii is: :i E-r ''l FJ; l- r s r+ss U f{ r E ci! :?: i; E : nl L *ii;i;i;ili j Eiii!igiaiiiiii il -3€ ;l jii = c-l Le s it5 ;gt,*:ii;$ii; Fi F \JU a .lS IU H\ sit! gi;iig: g lJr )< :,i S i rsr ii: is Ei :n*J f,'i;i;t: a- -r UJ { FJi .i' E-u+Efi€ E sa !E ei E i E F-r tr< ;E;: iE; 3?$s?s t-J ;: z r'l .-u*s re,,r gs E;ig;lii:ii;:ii*5t.! ti:; +-J \ \H trl - L9 \ gEi F-r 'Eq E;*it[; ;i;E iE Hr IE €i;i ! i*;: I tr-r s ct) i EE:i:r! t E;fe; s E;ttsE H;i;{i; sE+ FJ-l S aS H5; e '-\ q/ E th i st*E;iuF€;EEEFi;iE;'a:€:; g F! n1 Ii;:i 3;t g;:s :;sErr; i;:ti i;;i: :E F rt;;;igic; iitiTEi :E ;: r ;ac i; I;; FiE$es;i* Hsi s=+ qE H;{;5FH $;!iiEg tJ L-J S- Nll ^llo.\ ll e*[r+;sir{+giiiE gEa,E s;ee=ltlfFE E5sfr;r ; +rfi [FE 1:8;$ il r;*;rc*€ i'[;*+EI tl ;i ili$;l$s rgiT;i;licE;{ i;E;fi il5! f,r 1l ;lFaE€iHiiifx;a$;as -

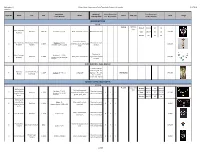

Maker-Muse-Addendum-A.Pdf

Addendum A Maker Muse: Women and Early Twentieth Century Art Jewelry 5/1/2018 Checklist Dimensions Mounting/ Mount Dimensions Case Dimensions Object No. Maker Title Date Media Case # Case Type Value Image H x W x D inches Installing Notes H x W x D inches H x W x D inches INTRODUCTION FC 1/6 FlatTable FC 1/6 Overall 50 1/4 36 20 Case Mrs. Charlotte 1 Pendant 1884-90 2 3/8 x 1 1/2 x 1/4 Gold, amethyst, enamel Mounted into deck - - - Case 38 1/4 36 20 $10,000 Newman Vitrine 12 36 12 Carved moonstone, Mrs. Charlotte Mary Queen of Scots Necklace: 20 1/2 Mounted on riser 2 c. 1890 amethyst, pearl, yellow gold - - - $16,500 Newman Pendant Pendant: 2 3/4 x 1 1/16 on deck chain Displayed in Mrs. Charlotte Necklace: L: 15 3/8 3 Necklace c. 1890 Gold, pearl, aquamarine original box directly - - - $19,000 Newman Pendant: 2 5/8 x 3 15/16 on deck INTRODUCTION - WALL DISPLAY Framed, D-Rings; wall hang; 68 - 72 Alphonse Sarah Bernhardt as 4 c. 1894 Framed: 96 x 41 x 2 Lithograph degrees F, 45 - 55% - - - Wall display $40,000 Mucha Gismonda RH, 5 - 7 foot candles (50 - 70 lux) BRITISH ARTS AND CRAFTS TC 1/10 TC 1/10 Large table Attributed to Overall 83 3/4 42 26 1/2 Gold, white enamel, case Jessie Marion Necklace: 5 11/16 Mounted on oval 5 Necklace c. 1905 chrysoberyl, peridot, green 8 6 1 Table 38 1/4 42 26 1/2 $11,000 King for Liberty Pendant: 2 x 13/16 riser on back deck garnet, pearl, opal & Co.