The Rise and Fall of the Oslo Peace Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians

U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians Jim Zanotti Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs August 12, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS22967 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians Summary Since the signing of the Oslo Accord in 1993 and the establishment of limited Palestinian self- rule in the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1994, the U.S. government has committed over $3.5 billion in bilateral assistance to the Palestinians. Since the death of Yasser Arafat in November 2004, U.S. assistance to the Palestinians has been averaging about $400 million a year. During the 1990s, U.S. foreign aid to the Palestinians averaged approximately $75 million per year. Despite more robust levels of assistance this decade, Israeli-Palestinian conflict and Hamas’s heightened role in Palestinian politics have made it more difficult to implement effective and lasting aid projects that serve U.S. interests. U.S. aid to the Palestinians has fluctuated considerably over the past five years, largely due to Hamas’s changing role within the Palestinian Authority (PA). After Hamas led the PA government for over a year, its forcible takeover of the Gaza Strip in June 2007 led to the creation of a non- Hamas government in the West Bank—resulting in different models of governance for the two Palestinian territories. Since then, the United States has dramatically boosted aid levels to bolster the PA in the West Bank and President Mahmoud Abbas vis-à-vis Hamas. The United States has appropriated or reprogrammed nearly $2 billion since 2007 in support of PA Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s security, governance, development, and reform programs, including $650 million for direct budgetary assistance to the PA and nearly $400 million (toward training, non-lethal equipment, facilities, strategic planning, and administration) for strengthening and reforming PA security forces and criminal justice systems in the West Bank. -

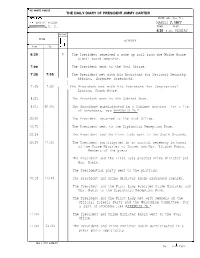

Ihe White House Iashington

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

S. Con. Res. 31

104TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION S. CON. RES. 31 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Whereas Yitzhak Rabin, a true hero of Israel, was born in Jerusalem on March 1, 1922; Whereas Yitzhak Rabin served in the Israel Defense Forces for more than two decades, and fought in three wars in- cluding service as Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces during the Six Day War of June 1967; Whereas Yitzhak Rabin served the people of Israel with great distinction in a number of government positions, includ- ing Ambassador to the United States from 1968 to 1973, Minister of Defense from 1984 to 1988, and twice as Prime Minister from 1974 to 1977 and from June 1992 until his assassination; Whereas under the leadership of Yitzhak Rabin, a framework for peace between Israel and the Palestinians was estab- lished with the signing of the Declaration of Principles on September 13, 1993, continued with the conclusion of a peace treaty between Israel and Jordan on October 26, 1994, and continues today; Whereas on December 10, 1994, Yitzhak Rabin was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace for his vision and accomplish- ments as a peacemaker; Whereas shortly before his assassination, Yitzhak Rabin said, ``I have always believed that the majority of the people 1 2 want peace and are ready to take a chance for peace. Peace is not only in prayers . but it is in the desire of the Jewish people.''; Whereas Yitzhak Rabin's entire life was dedicated to the cause of peace and security for Israel and its people; and Whereas on November 4, 1995, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated -

Meeting with MK Yossi Beilin

Meeting with MK Yossi Beilin On the evening of Thursday, March 22, 2007, Meretz Chairman Yossi Beilin addressed the Meretz USA board. He discussed current events surrounding the Winograd Commission, the formation of the Palestinian Unity government, and what the US should be doing, among other issues. Below is our staff summary of his remarks, supplemented by my observations– Ed. Winograd Commission & Government Corruption Dr. Beilin spoke first about an event that occurred on Thursday. Following a petition from Meretz MK Zahava Galon, the Israeli Supreme Court decided to publish the minutes of the Winograd testimonies. On Thursday, Shimon Peres’ testimony was made public. In it, Peres said he had been against the Lebanon war from the beginning , a fact that is also reflected in the Government Cabinet meeting minutes. Today, a rally of students asked him why, if he was against the war, did he vote for it? Peres answered that, as the Deputy Prime Minister, he did not feel that he could vote against the Prime Minister. In response, Dr. Beilin released a statement saying that those individuals who saw the danger of the war, but voted for it anyway, misled the country. Dr. Beilin also predicted upcoming changes in the Israeli government, although he said he did not believe there would be new elections. He indicated that most parties currently in the Knesset would not benefit by risking an election now. If Prime Minister Olmert is forced to step down by the corruption inquiry against him or by the Winograd Commission findings on the conduct of the recent war with Hezbollah, either Peres or Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni might replace him. -

The Oslo Accords and Hamas Response

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 9 September 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND HAMAS RESPONSE DR. BALAL ALI (ASSISTANT PROFESSOR) DEPARTMENT OF CIVICS AND ETHICAL STUDIES ADIGRAT UNIVERSITY, TIGRAY, ETHIOPIA) ABSTRACT The signing of Oslo Accords between Israel and PLO was a historic event. There were several factors and events which played vital role but the intifada that started in December 1987 was the milestone event which led to the Oslo Accords. Hamas which was founded during intifada in a very short time became the face and voice of Palestinian liberation movement but it was the Oslo Accords which gave impetus to the movement. Throughout the entire Oslo Peace Period Hamas adopted a very calculative strategy. On the one hand it continued to criticize PLO and its leadership for selling out Palestinian cause in exchange of millions of dollars and on the other hand remain committed to Jihad including revenge killings against Israel. Thus, Hamas was able to preserve its identity and legitimacy as well as its revenge killings were widely accepted because it was presumed as the best means to redress Israeli assassinations. All these factors along with other gradually made Hamas what it is today. KEY WORDS: Israel, Hamas, PLO, Intifada, Islam, Zionism, Palestine BACKGROUND OF THE OSLO ACCORDS The Oslo Accords and process need to be explained in thoroughly structural terms, with an eye to the long- term projects, strategies, policies, and powers of the Israeli state and the PLO.1 The road to Oslo was a long one for both Israelis and Palestinians. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1918

S1918 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE March 7, 2001 an agreement would remove a direct Foreigners increasingly are free to matically in recent years. U.S. exports North Korean threat to the region and travel widely in the country and talk to Southeast Asia, for instance, sur- improve prospects for North-South rec- to average North Koreans without gov- pass our exports to Germany and are onciliation. It would also remove a ernment interference. North Korea has double our exports to France. U.S. di- major source of missiles and missile even begun to issue tourist visas. The rect investment in East Asia now tops technology for countries such as Iran. presence of foreigners in North Korea $150 billion, and has tripled over the Getting an agreement will not be is gradually changing North Korean at- past decade. easy, but it helps a lot that we are not titudes about South Korea and the And of course these are just a few of the only country which would benefit West. the raw economic realities which un- from the dismantlement of North Ko- One American with a long history of derscore East Asia’s importance. The rea’s missile program. Our allies South working in North Korea illustrated the United States has important humani- Korea and Japan, our European allies change underway by describing an im- tarian, environmental, energy, and se- who already provide financial support promptu encounter he had recently. curity interests throughout the region. for the Agreed Framework, the Chi- While he was out on an unescorted We have an obligation, it seems to nese, the Russians, all share a desire to morning walk, a North Korean woman me, not to drop the ball. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

December 2007

People Ambssador of South Africa to Israel Middle East Digest Three years without Abu-Ammar Diplomatic Events editor The Diplomatic Club Magazine December 2007 Dear Friends, 2007 was an eventful year, during which the Middle-East –and the rest of the world. This year is now approaching its end. Despite the rapid end of the purely military phase of the Palestinian Conflict, the conflict is still raging, claiming too many lives. In Israel, the signing of the Roadmap has not yet generated the hoped for peace. We wish the Middle-East an active 2008 year focused on peace and development, where hatred dissolves and harmony blooms. To our readers, as always we would like to offer our best wishes for 2008: may your health be obvious (and need no discussion) may your family relations be warm may your friends be loyal may your enemies become your friends (and those who don’t, get lost) may your spam be filtered may your Emails be answered may your papers get published may your wisdom deserve the approval of Confucius, and your folly the praise of Erasmus may your power get shared, your wealth be free from greed and your poverty from envy may we communicate fruitfully across cultures so that our horizons widen and reason replaces violence The Diplomatic Club Magazine requests the pleasure to publish opinions, discussions and articles written by Ambassadors. We are looking forward to develop this idea. As the 2007 is now over, it is time to go back to work about new services for coming 2008 year. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

Israel, Palestine, and the Olso Accords

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 23, Issue 1 1999 Article 4 Israel, Palestine, and the Olso Accords JillAllison Weiner∗ ∗ Copyright c 1999 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Israel, Palestine, and the Olso Accords JillAllison Weiner Abstract This Comment addresses the Middle East peace process, focusing upon the relationship be- tween Israel and Palestine. Part I discusses the background of the land that today comprises the State of Israel and its territories. This Part summarizes the various accords and peace treaties signed by Israel, the Palestinians, and the other surrounding Arab Nations. Part II reviews com- mentary regarding peace in the Middle East by those who believe Israel needs to surrender more land and by those who feel that Palestine already has received too much. Part II examines the conflict over the permanent status negotiations, such as the status of the territories. Part III argues that all the parties need to abide by the conditions and goals set forth in the Oslo Accords before they can realistically begin the permanent status negotiations. Finally, this Comment concludes that in order to achieve peace, both sides will need to compromise, with Israel allowing an inde- pendent Palestinian State and Palestine amending its charter and ending the call for the destruction of Israel, though the circumstances do not bode well for peace in the Middle East. ISRAEL, PALESTINE, AND THE OSLO ACCORDS fillAllison Weiner* INTRODUCTION Israel's' history has always been marked by a juxtaposition between two peoples-the Israelis and the Palestinians 2-each believing that the land is rightfully theirs according to their reli- gion' and history.4 In 1897, Theodore Herzl5 wrote DerJeden- * J.D. -

Likud and the Oslo Process: Implications of a Hebron Accord

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 114 Likud and the Oslo Process: Implications of a Hebron Accord Jan 3, 1997 Brief Analysis f negotiators overcome eleventh-hour Palestinian demands and conclude an agreement on Hebron I redeployment, this accord would mark a milestone in the Middle East peace process: the first signed agreement between a Likud government and the Palestinians. With significant U.S. encouragement, the two sides will have managed to overcome the intense acrimony and bitterness that only three months ago claimed scores of lives and took the peace process to the precipice of collapse. The nearly hundred days of haggling since the Washington Summit -- sparked by the Netanyahu government's demand for improved security arrangements for the some 400 Israeli residents of Hebron and then fueled by Arafat's desire to take advantage of global sympathy to win concessions on non-Hebron issues -- may come to be seen by future historians as a critical turning point in the peace process, i.e., the moment when the Likud abandoned elements of its core ideology for the sake of accommodation with the Palestinians. The Hebron Conundrum: Israel's redeployment in Hebron completes the implementation of IDF withdrawals from the seven major Palestinian population centers, as called for in the September 1995 PLO-Israel accord (Oslo II). For the agreement's original Israeli negotiators, Hebron was such a thorny issue that its provisions outlining IDF redeployment from the city were separate and significantly more complex than those delineating withdrawal from other cities and towns in Gaza and the West Bank. Indeed, pulling IDF troops out of four-fifths of Hebron was seen as so potentially explosive and politically costly, that the Labor government of Shimon Peres balked at fulfilling that provision of the Oslo II accord. -

Using a Civil Suit to Punish/Deter Sponsors of Terrorism: Connecting Arafat & the PLO to the Terror Attacks in the Second In

Digital Commons at St. Mary's University Faculty Articles School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2014 Using a Civil Suit to Punish/Deter Sponsors of Terrorism: Connecting Arafat & the PLO to the Terror Attacks in the Second Intifada Jeffrey F. Addicott St. Mary's University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/facarticles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey F. Addicott, Using a Civil Suit to Punish/Deter Sponsors of Terrorism: Connecting Arafat & the PLO to the Terror Attacks in the Second Intifada, 4 St. John’s J. Int’l & Comp. L. 71 (2014). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING A CIVIL SUIT TO PUNISH/DETER SPONSORS OF TERRORISM: CONNECTING ARAFAT & THE PLO TO THE TERROR ATTACKS IN THE SECOND INTIFADA Dr. Jeffery Addicott* INTRODUCTION “All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”1 -Edmund Burke As the so-called “War on Terror” 2 continues, it is imperative that civilized nations employ every possible avenue under the rule of law to punish and deter those governments and States that choose to engage in or provide support to terrorism.3 *∗Professor of Law and Director, Center for Terrorism Law, St. Mary’s University School of Law.