Lalbagh Rethought Exploring the Incomplete Mughal Fortress in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Club Health Assessment MBR0087

Club Health Assessment for District 305 N1 through February 2016 Status Membership Reports LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice No Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Active Activity Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Email ** Report *** Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs less than two years old 125909 Faisalabad Lyallpur 10/21/2015 Active 20 20 0 20 100.00% 0 5 N/R 125553 Lahore First Women 08/06/2015 Active 23 21 0 21 100.00% 0 2 2 T 1 123036 Multan Family 09/02/2014 Active 16 2 14 -12 -42.86% 20 1 3 3 126227 Multan Imperial 12/10/2015 Newly 22 22 0 22 100.00% 0 3 N/R Chartered Clubs more than two years old 108273 BAHAWALPUR CHOLISTAN 05/12/2010 Cancelled(8*) 0 2 20 -18 -100.00% 16 2 2 None 14 64852 BUREWALA CRYSTAL 12/11/2001 Cancelled(8*) 0 0 11 -11 -100.00% 6 3 2 None 24+ 117510 FAISALABAD ACTIVE 08/14/2012 Active(1) 18 2 0 2 12.50% 16 2 4 N 2 98882 FAISALABAD AKAI 05/01/2008 Active 9 0 0 0 0.00% 9 3 8 S 3 50884 FAISALABAD ALLIED 08/06/1990 Active(1) 18 0 0 0 0.00% 18 7 -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Natural Landscapes & Gardens of Morocco 2022

Natural Landscapes & Gardens of Morocco 2022 22 MAR – 12 APR 2022 Code: 22206 Tour Leaders Paul Urquhart Physical Ratings Explore Morocco’s rich culture in gardening and landscape design, art, architecture & craft in medieval cities with old palaces and souqs, on high mountain ranges and in pre- Saharan desert fortresses. Overview This tour, led by garden and travel writer Paul Urquhart, is a feast of splendid gardens, great monuments and natural landscapes of Morocco. In Tangier, with the assistance of François Gilles, the UK’s most respected importer of Moroccan carpets, spend two days visiting private gardens and learn about the world of Moroccan interiors. While based in the charming Dar al Hossoun in Taroudant for 5 days, view the work of French landscape designers Arnaud Maurières and Éric Ossart, exploring their garden projects designed for a dry climate. View Rohuna, the stunning garden of Umberto Pasti, a well-known Italian novelist and horticulturalist, which preserves the botanical richness of the Tangier region. Visit the gardens of the late Christopher Gibbs, a British antique dealer and collector who was also an influential figure in men’s fashion and interior design in 1960s London. His gorgeous cliff-side compound is set in 14 acres of plush gardens in Tangier. In Marrakesh, visit Yves Saint Laurent Museum, Jardin Majorelle, the Jardin Secret, the palmeraie Jnane Tamsna, André Heller’s Anima and take afternoon tea in the gardens of La Mamounia – one of the most famous hotels in the world. Explore the work of American landscape architect, Madison Cox: visit Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé’s private gardens of the Villa Oasis and the gardens of the Yves Saint Laurent Museum in Marrakesh. -

Prof. Kanu BALA-Bangladesh: Professor of Ultrasound and Imaging

Welcome To The Workshops Dear Colleague, Due to increasing demands for education and training in ultrasonography, World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology has established its First "WFUMB Center of Excellence" in Dhaka in 2004. Bangladesh Society of Ultrasonography is the First WFUMB Affiliate to receive this honor. The aims of the WFUMB COE is to provide education and training in medical ultrasonography, to confer accreditation after successful completion of necessary examinations and to accumulate current technical information on ultrasound techniques under close communication with other Centers, WFUMB and WHO Global Steering Group for Education and Teaching in Diagnostic Imaging. 23 WFUMB Center of Education Workshop of the World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology will be held jointly in the City of Dhaka on 6 & 7 March 2020. It is a program of “Role of Ultrasound in Fetal Medicine” and will cover some new and hot areas of diagnostic ultrasound. It’s First of March and it is the best time to be in Dhaka. So block your dates and confirm your registration. Yours Cordially Prof. Byong Ihn Choi Prof. Mizanul Hasan Director President WFUMB COE Task Force Bangladesh Society of Ultrasonography Prof. Kanu Bala Prof. Jasmine Ara Haque Director Secretary General WFUMB COE Bangladesh Bangladesh Society of Ultrasonography WFUMB Faculty . Prof. Byung Ihn Choi-South Korea: Professor of Radiology. Expert in Hepatobiliary Ultrasound, Contrast Ultrasound and Leading Edge Ultrasound. Director of the WFUMB Task Force. Past President of Korean society of Ultrasound in Medicine. Past President of the Asian Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. -

Ijarset 13488

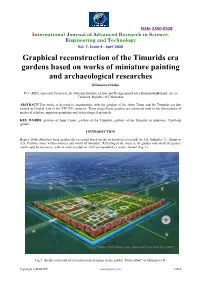

ISSN: 2350-0328 International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 7, Issue 4 , April 2020 Graphical reconstruction of the Timurids era gardens based on works of miniature painting and archaeological researches GilmanovaNafisa P.G. (PhD), Associate Professor, the National Institute of Arts and Design named after KamoliddinBehzad, city of Tashkent, Republic of Uzbekistan ABSTRACT:This article is devoted to acquaintance with the gardens of the Amir Timur and the Timurids era that existed in Central Asia in the XIV-XV centuries. These magnificent gardens are preserved only in the descriptions of medieval scholars, miniature paintings and archaeological materials. KEY WORDS: gardens of Amir Timur, gardens of the Timurids, gardens of the Timurids in miniature, Charbagh garden. I.INTRODUCTION Bagh-e Dolat-Abad has been graphically recreated based on the archaeological records by I.A. Sukharev, U. Alimova, A.S. Uralova, some written sources and works of miniature. Referring to the sources, the garden was small, the palace itself could be two-story, with an iwan, located on a hill surrounded by a water channel (Fig. 1). Fig 1. Architectural and art reconstruction of image of the garden “Dolat-Abad” of Gilmanova N. Copyright to IJARSET www.ijarset.com 13488 ISSN: 2350-0328 International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 7, Issue 4 , April 2020 Bagh-e Dolat-Abad Garden, located south of Samarkand, was built upon the return of Amir Timur from the Indian campaign in 1399. Describing the Dolat-Abad Garden, from which only architectural fragments of the foundation of the magnificent palace on a hill were preserved, Clavijo stated: “Clay rampart surrounded the garden. -

Lalbagh: an Incomplete Depiction of Mughal Garden in Bangladesh Farzana Sharmin Hfwu Nürtingen Geislingen, [email protected]

Proceedings of the Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning Volume 6 Adapting to Expanding and Contracting Article 21 Cities 2019 Lalbagh: an Incomplete Depiction of Mughal Garden in Bangladesh Farzana Sharmin HfWU Nürtingen Geislingen, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/fabos Part of the Environmental Design Commons, Geographic Information Sciences Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Landscape Architecture Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Remote Sensing Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Sharmin, Farzana (2019) "Lalbagh: an Incomplete Depiction of Mughal Garden in Bangladesh," Proceedings of the Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning: Vol. 6 , Article 21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7275/pcnk-h124 Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/fabos/vol6/iss1/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sharmin: Lalbagh: an Incomplete Depiction of Mughal Garden in Bangladesh Lalbagh: an Incomplete Depiction of Mughal Garden in Bangladesh Farzana Sharmin HfWU Nürtingen Geislingen Abstract Lalbagh Fort Complex is one of the extravagant examples built by the Mughal Empire in Bangladesh, documented in UNESCO World Heritage tentative List. While there are several Mughal structures found in the Indian sub-continent, this incomplete fort is the only footprint of encamped Mughal garden style that remains in the capital of Bengal, Jahangirnagar (now Dhaka). -

Watching, Snorkelling, Whale-Watching

© Lonely Planet Publications 202 Index A Baitul Mukarram Mosque 55 Rocket 66-7, 175, 6 accommodation 157-8 baksheesh 164 to/from Barisal 97-8 activities, see diving, dolphin- Baldha Gardens 54 to/from Chittagong 127-8 watching, snorkelling, Bana Vihara 131 to/from Dhaka 66-8 whale-watching Banchte Shekha Foundation 81 boat trips 158 Adivasis 28, 129, see also individual Bandarban 134-6 Chittagong 125-6 tribes bangla 31 Dhaka 59 Agrabad 125 Bangla, see Bengali Mongla 90 Ahmed, Fakhruddin 24 Bangladesh Freedom Fighters 22 Rangamati 131 Ahmed, Iajuddin 14 Bangladesh Nationalist Party 23 Sariakandi 103 INDEX Ahsan Manzil 52 Bangladesh Tea Research Institute 154 Bogra 101-3, 101 air travel Bangsal Rd 54 books 13, 14, see also literature airfares 170 Bara Katra 53 arts 33 airlines 169-70 Bara Khyang 140 birds 37 to/from Bangladesh 170-2 Barisal 97-9, 98 Chittagong Hill Tracts 28, 29 within Bangladesh 173-5 Barisal division 96-9 culture 26, 27, 28, 31 Ali, Khan Jahan 89 Baro Bazar Mosque 82 emigration 32 Ananda Vihara 145 Baro Kuthi 115 food 40 animals 36, 154-5, see also individual bathrooms 166 history 20, 23 animals Baul people 28 Lajja (Shame) 30 Lowacherra National Park 154-5 bazars, see markets tea 40 Madhupur National Park 77-8 beaches border crossings 172 Sundarbans National Park 93-4, 7 Cox’s Bazar 136 Benapole 82 architecture 31-2, see also historical Himachari Beach 139 Burimari 113 buildings Inani Beach 139 Tamabil 150 area codes 166, see also inside front Benapole 82 Brahmaputra River 35 cover Bengali 190-6 brassware 73 Armenian -

Ebook Download Islamic Geometric Patterns Ebook, Epub

ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Eric Broug | 120 pages | 13 May 2011 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500287217 | English | London, United Kingdom Islamic Geometric Patterns PDF Book You May Also Like. Construction of girih pattern in Darb-e Imam spandrel yellow line. Charbagh Mughal Ottoman Paradise Persian. The circle symbolizes unity and diversity in nature, and many Islamic patterns are drawn starting with a circle. Main article: Shabaka window. Pair of Minbar Doors. MC Escher: the graphic work. But auxetic materials expand at right angles to the pull. The strapwork cuts across the construction tessellation. Scientific American 1 Classification of a pattern involves repeating the unit-design by isometry formulas translation, mirroring, rotation and glide reflections to generate a pattern that can be classified as 7-freize patterns or the wallpaper patterns. Tarquin Publications. Islamic geometric patterns. For IEEE to continue sending you helpful information on our products and services, please consent to our updated Privacy Policy. They form a three-fold hierarchy in which geometry is seen as foundational. The researcher traced the existing systems associated with the classification of Islamic geometric patterns i. The Arts of Ornamental Geometry. Because weaving uses vertical and horizontal threads, curves are difficult to generate, and patterns are accordingly formed mainly with straight edges. Iran Persia , — A. Muqarnas are elaborately carved ceilings to semi-domes , often used in mosques. These may constitute the entire decoration, may form a framework for floral or calligraphic embellishments, or may retreat into the background around other motifs. Eva Baer [f] notes that while this design was essentially simple, it was elaborated by metalworkers into intricate patterns interlaced with arabesques, sometimes organised around further basic Islamic patterns, such as the hexagonal pattern of six overlapping circles. -

Sacred Right Defiled: China’S Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom

Sacred Right Defiled: China’s Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom A Report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project Table of Contents Executive Summary...........................................................................................................2 Methodology.......................................................................................................................5 Background ........................................................................................................................6 Features of Uyghur Islam ........................................................................................6 Religious History.....................................................................................................7 History of Religious Persecution under the CCP since 1949 ..................................9 Religious Administration and Regulations....................................................................13 Religious Administration in the People’s Republic of China................................13 National and Regional Regulations to 2005..........................................................14 National Regulations since 2005 ...........................................................................16 Regional Regulations since 2005 ..........................................................................19 Crackdown on “Three Evil Forces”—Terrorism, Separatism and Religious Extremism..............................................................................................................23 -

Natural Landscapes & Gardens of Morocco

Natural Landscapes & Gardens of Morocco 18 APR – 9 MAY 2017 Code: 21704 Tour Leaders Sabrina Hahn Physical Ratings Explore Morocco’s rich culture in gardening and landscape design, art, architecture & craft in medieval cities with old palaces and souqs, on high mountain ranges and in pre- Saharan desert fortresses. Overview Tour Highlights This tour, led by Sabrina Hahn, horticulturalist, garden designer and expert gardening commentator on ABC 720 Perth, is a feast of splendid gardens, great monuments and natural landscapes of Morocco. In Tangier, with the assistance of François Gilles, the UK's most respected importer of Moroccan carpets, spend two days visiting a variety of private gardens and learning about the world of Moroccan interiors. François' work has been featured in many publications such as World of Interiors, House & Garden, Sunday Telegraph, and many more. While based in a charming dar in Taroudant for 6 days, join renowned French landscape designers Arnaud Maurières and Éric Ossart, exploring their garden projects designed for a dry climate. Explore the work of American landscape architect, Madison Cox, with a visit to Pierre Bergé's Villa Léon L’Africain and Villa Mabrouka in Tangier. View the stunning garden of Umberto Pasti, a well-known Italian novelist and horticulturalist, whose garden is a 'magical labyrinth of narrow paths, alleyways and walled enclosures'. Enjoy lunch at the private residence of Christopher Gibbs, a British antique dealer and collector who was also an influential figure in men’s fashion and interior design in 1960s London. His gorgeous cliff- side compound is set in 14 acres of plush gardens. -

Aesthetics of the Qur'anic Epigraphy on the Taj Mahal

Aesthetics of the Qur’anic Epigraphy on the Taj Mahal by Rio Fischer B.A. Philosophy & Middle Eastern Studies Claremont McKenna College, 2012 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2017 ©2017 Rio Fischer. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: __________________________________________________ Department of Architecture May 25, 2017 Certified by: __________________________________________________________ James Wescoat Aga Khan Professor Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:__________________________________________________________ Sheila Kennedy Professor of Architecture Chair, Department Committee on Graduate Students Committee: James Wescoat, PhD Aga Khan Professor Thesis Supervisor Nasser Rabbat, MArch, PhD Aga Khan Professor Thesis Reader 3 Aesthetics of the Qur’anic Epigraphy on the Taj Mahal by Rio Fischer Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 25, 2017 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the Qur’anic epigraphic program of the Taj Mahal. Following the 1989 Begley & Desai book Taj Mahal: an Illustrated Tomb, the flourish of scholarship that would expectedly follow a complete epigraphical catalog never arrived. Despite being well-known and universally cherished as indicated by the Taj Mahal’s recognition as a UNESCO world heritage monument and as one of the New 7 Wonders of the World, there is insufficient research directed towards the inscription program specifically. -

Evolution of Delhi Architecture and Urban Settlement Author: Janya Aggarwal Student at Sri Guru Harkrishan Model School, Sector -38 D, Chandigarh 160009 Abstract

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 11, Issue 10, October-2020 862 ISSN 2229-5518 Evolution of Delhi Architecture and Urban Settlement Author: Janya Aggarwal Student at Sri Guru Harkrishan Model School, Sector -38 D, Chandigarh 160009 Abstract Delhi remains one of the oldest surviving cities in the world today. It is in fact, an amalgam of eight cities, each built in a different era on a different site – each era leaving its mark, and adding character to it – and each ruler leaving a personal layer of architectural identity. It has evolved into a culturally secular city – absorbing different religions, diverse cultures, both foreign and indigenous, and yet functioning as one organic. When one thinks of Delhi, the instant architectural memory that surfaces one’s mind is one full of haphazard house types ranging from extremely wealthy bungalows of Lutyens’ Delhi to very indigenous bazaar-based complex settlements of East Delhi. One wonders what role does Architecture in Delhi have played or continue to assume in deciding the landscape of this ever changing city. Delhi has been many cities. It has been a Temple city, a Mughal city, a Colonial and a Post-Colonial city.In the following research work the development of Delhi in terms of its architecture through difference by eras has been described as well as the sprawl of urban township that came after that. The research paper revolves around the architecture and town planning of New Delhi, India. The evolution of Delhi from Sultanate Era to the modern era will provide a sense of understanding to the scholars and the researchers that how Delhi got transformed to New Delhi.