Groundtruth: a FIELD GUIDE for CORRESPONDENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations A/HRC/17/44

United Nations A/HRC/17/44 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 January 2012 Original: English Human Rights Council Seventeenth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situation that require the Council’s attention Report of the International Commission of Inquiry to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya* Summary Pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution S-15/1 of 25 February 2011, entitled “Situation of human rights in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya”, the President of the Human Rights Council established the International Commission of Inquiry, and appointed M. Cherif Bassiouni as the Chairperson of the Commission, and Asma Khader and Philippe Kirsch as the two other members. In paragraph 11 of resolution S-15/1, the Human Rights Council requested the Commission to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, to establish the facts and circumstances of such violations and of the crimes perpetrated and, where possible, to identify those responsible, to make recommendations, in particular, on accountability measures, all with a view to ensuring that those individuals responsible are held accountable. The Commission decided to consider actions by all parties that might have constituted human rights violations throughout Libya. It also considered violations committed before, during and after the demonstrations witnessed in a number of cities in the country in February 2011. In the light of the armed conflict that developed in late February 2011 in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya and continued during the Commission‟s operations, the Commission looked into both violations of international human rights law and relevant provisions of international humanitarian law, the lex specialis that applies during armed conflict. -

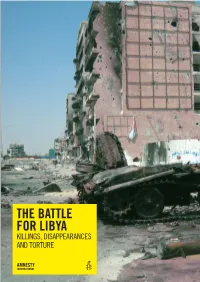

The Battle for Libya

THE BATTLE FOR LIBYA KILLINGS, DISAPPEARANCES AND TORTURE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2011 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2011 Index: MDE 19/025/2011 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo : Misratah, Libya, May 2011 © Amnesty International amnesty.org CONTENTS Abbreviations and glossary .............................................................................................5 Introduction .................................................................................................................7 1. From the “El-Fateh Revolution” to the “17 February Revolution”.................................13 2. International law and the situation in Libya ...............................................................23 3. Unlawful killings: From protests to armed conflict ......................................................34 4. -

DATE June 6, 1980

I . MONTHLY SUBSCRIPTION FEE (WITHOUT REPRODUCTION RIGHTS) . ·" · FRENCH FRANCS:~2$ . ·(AIR MAIL POSTAGE CHARGES EXCLUDED) 11,13, 11, PLACE DE LA BOURSE 75002 PARIS TEL: 233.44.11 TELEX 210014 DATE June 6, 1980 •I , ... ,;, I;' ~ -· • '•a. j l ·~· •• I ' • Indlpendmmren.t de 4art 4~ d'In0alallttion.6 gldltatu, l.' AGCNCE FR.ANC'E- PRESS! c:Ll.o 6u.6e., rilz1r4 toub. !a. FIWlC.e. u cz'an4 c.~ 'fJ4IJ4 Wll.Qple.n4, un "Se~t.\1-i.ee. d' .i.n6alallttion4 Ec.anomig&L~A pcut TUu~lll. 11 (s.!. t. 1• L'A.F.?. pubtie, d'~ p~, tu but!etin4 4plc.i4- .ti.6l6 41ki.\la.n.tA : I • PoUlt tou.6 lttn4e.tgnure.n.t4, 4 'adltt44elt cl !'AGENCc FRANC!-?RESSc 13, 1S, p!a.c.e. de. .ta. SaUIC.4e -· 15002 PARIS - Se~tv.i.c.e. ComtUtelczl TEL. 233.44.66 - po4~e. 4442 AFP AFRICA N° 2695 June 6, 1980 S U M M A R Y ===================' GENERAL INFORMATION Paris : OECD : difficult period ahead 1 Dar-es-Salaam : Foreign help needed 2 London : Tin for 30 years 2 Dar-es-Salaam : Brazil won't join nontaligned 3 New Orleans : "Intolerable" inflation 3 London : The poor, the rich 4 OIL & ENERGY Lagos : Nigeria : 2 dollars 4 Paris : Gas for 45 years 4 Paris : Reunification theme 5 Madrid : Cactus solution 6 MIDDLE EAST Muscat : Oman : "No bases" 6 Teheran : u.s. condemned 7 Boston: Espionage loophole ••• 7 Washington : Land and port 8 Washington : "Cool down" plea 8 NORTH AFRICA General Information : - Royal ;isitors 9 Libya : - !ndividual killers ••• 9 Algeria : ( -Democratic dialogue ••• 10 ~ Egypt : \ -Menace of communism ••• 11 Morocco : ( ' - Health agreement 11 \ Tunisia ( - Travel protest 11 Sahara : I -Threat to OAU ••• 12 t - Madagascan ban 12 I WEST AFRICA \ General Information : \ - Funds for Sahel 13 Ghana : - Reprisals, says rawlings 13 Liberia - Tolbert money 14 - u.s. -

LIBYA CONFLICT: SITUATION UPDATE May 2011

U.S. & Coalition Operations and Statements LIBYA CONFLICT: SITUATION UPDATE May 2011 MAY 27: Russia has shifted its position on Libya and now believes Qaddafi has lost the legitimacy to rule and should leave power. Russia has offered to mediate a ceasefire and negotiate his departure with senior members of Qaddafi’s inner-circle. The pivot in Russian policy comes after a meeting between President Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev Russian at the G8 summit in France. Prime Minister Vladimir Putin has been highly critical of the NATO bombing campaign and Medvedev’s earlier decision to not veto the U.N Security Council resolution authorizing the allied action. After Medvedev’s decision, Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said, “Colonel Gaddafi has deprived himself of legitimacy with his actions, we should help him leave.” New( York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Reuters, Reuters, Al-Jazeera) MAY 27: The G8 nations announced in their joint summit communiqué that Qaddafi had no future role in a democratic Libya and the group demanded the regime’s forces cease their attacks against civilians. The communiqué stated that those behind the killing of civilians would be investigated and punished. (Reuters) MAY 27: British officials cleared the use of attack helicopters in Libya on Thursday. British officials have said that the addition of British Apaches and French Tiger helicopters into the battle will allow for low-level, precision attacks on urban targets, including Libyan officials. In a shift, the helicopters will be operated under NATO command instead of national command, NATO officials said that four Apache attack helicopters were available from the assault ship HMS Ocean as well as four Tigers aboard the French helicopter carrier Tonnerre. -

Arab Spring” June 2012

A BBC Trust report on the impartiality and accuracy of the BBC’s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring” June 2012 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers A BBC Trust report on the impartiality and accuracy of the BBC‟s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring” Contents BBC Trust conclusions 1 Summary 1 Context 2 Summary of the findings by Edward Mortimer 3 Summary of the research findings 4 Summary of the BBC Executive‟s response to Edward Mortimer‟s report 5 BBC Trust conclusions 6 Independent assessment for the BBC Trust by Edward Mortimer - May 2012 8 Executive summary 8 Introduction 11 1. Framing of the conflict/conflicts 16 2. Egypt 19 3. Libya 24 4. Bahrain 32 5. Syria 41 6. Elsewhere, perhaps? 50 7. Matters arising 65 Summary of Findings 80 BBC Executive response to Edward Mortimer’s report 84 The nature of the review 84 Strategy 85 Coverage issues 87 Correction A correction was made on 25 July 2012 to clarify that Natalia Antelava reported undercover in Yemen, as opposed to Lina Sinjab (who did report from Yemen, but did not do so undercover). June 2012 A BBC Trust report on the impartiality and accuracy of the BBC‟s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring” BBC Trust conclusions Summary The Trust decided in June 2011 to launch a review into the impartiality of the BBC‟s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring”. In choosing to focus on the events known as the “Arab Spring” the Trust had no reason to believe that the BBC was performing below expectations. -

Bentley, Gareth (2013) Journalistic Agency and the Subjective Turn in British Foreign Correspondent Discourse

Bentley, Gareth (2013) Journalistic agency and the subjective turn in British foreign correspondent discourse. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/17353 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. 1 Journalistic agency and the subjective turn in British foreign correspondent discourse Gareth Bentley Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Media Studies 2013 Centre for Media and Film Studies School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Libya | Freedom House

Libya | Freedom House http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2012/libya About Us DONATE Blog Contact Us REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Donate FREEDOM OF THE PRESS - View another year - Libya Libya Freedom of the Press 2012 2012 ﻋﺮﺑﻲ Status change explanation: Libya improved from Not Free to Partly Free due to SCORES significant improvements in media freedom and access to information as Mu’ammar al-Qadhafi’s control over the country progressively crumbled during PRESS STATUS 2011. The draft constitution contains provisions for expanded freedom of expression and of the press, and access to officials is far greater than under the Partly Qadhafi regime. There has also been a boom of media outlets, particularly in the east, with a diversity of viewpoints. Journalists are able to cover the news more Free freely than before, and with less threat of violence and intimidation. PRESS FREEDOM SCORE Prior to the 2011 uprising that led to the overthrow of longtime leader Mu’ammar al-Qadhafi, the Libyan media were among the most tightly controlled 60 in the world. However, following al-Qadhafi’s downfall, the media environment in LEGAL Libya experienced a transformation. The revolution began in February, when ENVIRONMENT citizens in several Libyan cities—inspired by early 2011 uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt—took to the streets to protest al-Qadhafi’s 42-year rule, sparking a brutal 16 crackdown by the regime. Libyan civilians and army defectors took up arms in response to the regime’s attacks, and in March, a NATO-led campaign of POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT airstrikes was launched to protect civilians. -

Journalists Under Fire 00-Tumber-Prelims.Qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page Ii 00-Tumber-Prelims.Qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page Iii

00-Tumber-Prelims.qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page i Journalists Under Fire 00-Tumber-Prelims.qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page ii 00-Tumber-Prelims.qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page iii Journalists Under Fire Information War and Journalistic Practices Howard Tumber and Frank Webster SAGE Publications London ●●Thousand Oaks New Delhi 00-Tumber-Prelims.qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page iv © Howard Tumber and Frank Webster 2006 First published 2006 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP SAGE Publications Inc. 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B-42, Panchsheel Enclave Post Box 4109 New Delhi 110 017 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN-10 1-4129-2406-5 ISBN-13 978-1-4129-2406-1 ISBN-10 1-4129-2407-3 (pbk) ISBN-13 978-1-4129-2407-8 Library of Congress Control Number available Typeset by C&M Digitals (P) Ltd., Chennai, India Printed in Great Britain by Athenaeum Press, Gateshead Printed on -

Informe-Anual-2011-RSF.Pdf

INFORME ANUAL 2011 LA LIBERTAD DE PRENSA EN EL MUNDO 2011 Coordinación y maquetación: Lucía Campoamor Con la colaboración de: Joaquín Calvente Todos datos de este informe proceden de la información elaborada por Reporteros Sin Fronteras en sus notas de prensa, informes, y visitas sobre el terreno a diferentes países. Los datos estadísticos relativos a los países (superficie y población) proceden del Atlas Eco 2011 (Nouvel Observateur). © Reporteros Sin Fronteras 2011 María de Molina, 50– 28006 Madrid Tel: + 34 91 523 37 00 – Fax: + 34 91 522 93 83 E-mail: [email protected] Informe Anual 2011 pág. 2 BARÓMETRO DE LA LIBERTAD DE PRENSA 2011 Periodistas asesinados..............66 Colaboradores asesinados...........2 Periodistas encarcelados.........171 Colaboradores encarcelados.......9 Internautas encarcelados........129 Informe Anual 2011 pág. 3 ÍNDICE Introducción General pág. 5 Uganda pág. 51 Birmania pág. 111 Grecia pág. 162 Zambia pág. 54 Camboya pág. 113 Hungría pág. 163 África Zimbabue pág. 55 China pág. 114 Italia pág. 164 Introducción pág. 8 Corea del Norte pág. 121 Letonia pág. 165 Angola pág. 11 América Filipinas pág. 122 Moldavia pág. 166 Benín pág. 12 Introducción pág. 57 India pág. 123 Portugal pág. 167 Burundi pág. 13 Argentina pág. 60 Indonesia pág. 125 República Checa pág. 168 Camerún pág. 14 Bolivia pág. 62 Malasia pág. 127 Rusia pág. 169 Comores pág. 15 Brasil pág. 64 Nepal pág. 129 Turquía pág. 172 Costa de Marfil pág. 16 Chile pág. 66 Pakistán pág. 130 Ucrania pág. 174 Djibouti pág. 19 Colombia pág. 68 Sri Lanka pág. 131 Eritrea pág. 20 Cuba pág. 71 Tailandia pág. -

Libya in Conflict: Mapping the Libyan Conflict

Preface The purpose of this legal memo and research project is to identify and analyze the various war crimes, crimes against humanity, and Libyan domestic crimes perpetrated during the Libyan armed conflict between February and October of 2011. This project was conducted by Syracuse University College of Law graduate students, René Moya and Mikala Steenholdt, with the assistance of Professors David M. Crane and Corri Zoli, for the Institute for National Security and Counterterrorism (INSCT), a joint research center at the College of Law and the Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs, Syracuse University. Readers should view the project in the following sequence: (1) consult, first, the slideshow in the compact disc in Appendix D; (2) then, turn to the legal memorandum; and (3) finally, examine the war crime matrix. In this fashion, readers may visually and conceptually “map” the conflict holistically, become familiar with the detailed documented evidence of violations of international and domestic norms, and finally situate those violations within the context of the unfolding crisis. Although this memorandum reviews all allegations of war crimes and crimes against humanity1 on all sides, including Libyan national forces, Libyan rebels, mercenaries, and NATO forces, it generally focuses on the crimes perpetrated by the Libyan national armed forces as the facts revealed that they were responsible for the majority of alleged violations. Report Review Slideshow Memorandum Crime Matrix 1 We have analyzed the crimes based on the Rome Statute; however, the crime matrix also includes the analysis of crimes under the Libyan Penal Code. i | P a g e CONTENTS I. -

TIME in Memory of Photographers We Lost in 2011

galleryluisotti at Bergamot Station 2525 Michigan Ave. number a2 Santa Monica California 90404 tel. 310 453 0043 fax 310 264 4888 [email protected] In Memory of Photographers We Lost In 2011 by Nate Rawlings December 20, 2011 They went by several different names. James Atherton was a “news photographer” while Tim Hetherington preferred “image maker.” We just call them photographers. They make images, yes, often connected with the news. But they actually record the world–in all of its beauty, horror, pain and confusion–at a particular time and place. For three of the photographers who were killed covering the civil war in Libya this year, the uprising to oust Muammar Gaddafi was far from their first experience in combat. Anton Hammerl, a South African who lived in London, documented violence in South African townships before the 1994 election. After years far from the sound of the guns, Hammerl traveled to Libya and went missing in Brega on April 5, along with two other journalists. Only when the other two were released by Gaddafi forces did Hammerl’s family learn that he had been killed. The news would come more quickly for the families of Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros. On April 20, a mortar round crashed in the middle of a group of photographers covering the fighting in the city of Misrata. Hetherington and Hondros both died of their wounds. Hondros had covered Liberia and Iraq, among other conflicts, including the 2003 photo of a Liberian militia commander jumping elatedly in the air after firing a rocket-propelled grenade at rebels holding a key bridge in Monrovia. -

Table of Membership Figures For

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D.