Mayor's Transport Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

How to Enhance Walking and Cycling Instead of Shorter Car Trips and to Make These Modes Safer

Deliverable D6 How to enhance WALking and CYcliNG instead of shorter car trips and to make these modes safer Public WALCYNG Contract No: UR-96-SC.099 Project Coordinator: Department of Traffic Planning and Engineering, University of Lund, Sweden Partners: FACTUM Chaloupka, Praschl & Risser OHG Franco Gnavi and Carlo Bonanni City of Helsinki, City Planning Office Institute of Transport Economics Department of Psychology, University of Helsinki Instituto de Tráfico y Seguridad Vial (INTRAS), University of Valencia TransportTechnologie-Consult Karlsruhe GmbH Dutch Pedestrian Association "De Voetgangersvereniging" Chalmers University of Technology AB (Associated Contractor) Date: 15.1.1999 PROJECT FUNDED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION UNDER THE TRANSPORT RTD PROGRAMME OF THE 4th FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME Deliverable D6 WALCYNG How to enhance WALking and CYcliNG instead of shorter car trips and to make these modes safer Public Hydén, C., Nilsson, A. & Risser, R. Department of Traffic Planning and Engineering, University of Lund, Sweden & FACTUM Chaloupka, Praschl & Risser OHG, Vienna, Austria 6. Department of Psychology, University of Helsinki, Liisa Hakamies-Blomqvist, Finland 7. INTRAS, University of Valencia, Enrique J. Carbonell Vayá, Beatriz Martín, Spain 8. Transport Technologie-Consult Karlsruhe GmbH (former Verkehrs-Consult Karlsruhe), Rainer Schneider, Germany 9. De Voetgangersvereniging, Willem Vermeulen, The Netherlands 10. Road and Traffic Planning Department, Chalmers University of Technology AB, Olof Gunnarsson, Sweden TABLE OF CONTENTS -

London Councils Housing Forum Executive Meeting

London Councils’ Transport & Environment Committee Chair’s Report Item no: 07 Report by: Katharina Winbeck Job title: Head of Transport and Environment Date: 19 March 2015 Contact Officer: Katharina Winbeck Telephone: 020 7934 9945 Email: [email protected] Summary This report updates Members on transport and environment policy since the last TEC meeting on 11 December 2014 and provides a forward look until the next TEC meeting on 11 June 2015. Recommendations Members to note this report. Update included in this report: Portfolio holder meeting with Chair of London Councils Transport Meeting between TEC and TfL Commissioner A new freight strategy for London Office of Low Emission Vehicles ‘Go Ultra Low City scheme’ joint bid with GLA and TfL Crossrail 2 Source London Update Ultra Low Emission Zone consultation response Environment Bellwin scheme consultation response Spitting byelaw Thames Regional Flood and Coastal Committee (TRFCC) Green Infrastructure Task Force Forward Look Chair’s Report London Councils’ TEC – 19 March 2015 Agenda Item 7, Page 1 Introduction 1. This report updates Members on London Councils’ work on transport and environment policy since the last TEC meeting on 11 December 2014 and provides a forward look until 18 June 2015. Portfolio holder briefing with Chair of London Councils 2. I met with Mayor Jules Pipe and London Councils officers to discuss the priorities for the year 2015/16. We agreed to focus our efforts on two areas; • Work with Government and TfL to ensure that current funding levels remain or are improved • Explore ways in which the borough contribution can be strengthened and improved through further collaboration With the key aims being; • Achieving a better deal on utility bills for both residents and boroughs to reduce fuel poverty in the Capital and achieve much needed savings. -

Submissions to the Call for Evidence from Organisations

Submissions to the call for evidence from organisations Ref Organisation RD - 1 Abbey Flyer Users Group (ABFLY) RD - 2 ASLEF RD - 3 C2c RD - 4 Chiltern Railways RD - 5 Clapham Transport Users Group RD - 6 London Borough of Ealing RD - 7 East Surrey Transport Committee RD – 8a East Sussex RD – 8b East Sussex Appendix RD - 9 London Borough of Enfield RD - 10 England’s Economic Heartland RD – 11a Enterprise M3 LEP RD – 11b Enterprise M3 LEP RD - 12 First Great Western RD – 13a Govia Thameslink Railway RD – 13b Govia Thameslink Railway (second submission) RD - 14 Hertfordshire County Council RD - 15 Institute for Public Policy Research RD - 16 Kent County Council RD - 17 London Councils RD - 18 London Travelwatch RD – 19a Mayor and TfL RD – 19b Mayor and TfL RD - 20 Mill Hill Neighbourhood Forum RD - 21 Network Rail RD – 22a Passenger Transport Executive Group (PTEG) RD – 22b Passenger Transport Executive Group (PTEG) – Annex RD - 23 London Borough of Redbridge RD - 24 Reigate, Redhill and District Rail Users Association RD - 25 RMT RD - 26 Sevenoaks Rail Travellers Association RD - 27 South London Partnership RD - 28 Southeastern RD - 29 Surrey County Council RD - 30 The Railway Consultancy RD - 31 Tonbridge Line Commuters RD - 32 Transport Focus RD - 33 West Midlands ITA RD – 34a West Sussex County Council RD – 34b West Sussex County Council Appendix RD - 1 Dear Mr Berry In responding to your consultation exercise at https://www.london.gov.uk/mayor-assembly/london- assembly/investigations/how-would-you-run-your-own-railway, I must firstly apologise for slightly missing the 1st July deadline, but nonetheless I hope that these views can still be taken into consideration by the Transport Committee. -

Public Transport

Public Transport Submission David Kilsby February 2009 Prepared for: Prepared by: Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport (RRAT) Standing Kilsby Australia Pty Ltd Cmomittee ACN 092 084 743 inquiry into Public Transport 20/809 Pacific Highway Department of the Senate Chatswood PO Box 6100 NSW 2067 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 +61 2 9415 4544 www.kilsby.com.au Public Transport Contents Page 1.1.1. SUMMARYSUMMARY................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................ ................................... 111 2.2.2. CREDENTIALS ................................................................................... ................................................................................................ ................................................................................................ ....................... 222 3.3.3. PEAK OIL AND PUBLIC TRANSPORTTRANSPORT................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................... 444 4.4.4. TERMS OF REFERENCE ................................................................................... ............................................................................................... -

Demand Side Policy – Vehicle Charging Schemes in London

Demand Side Policy – Vehicle charging schemes in London Simon Roberts – Principal City Planner, Transport for London Background London and the Role of the Mayor and TfL • Population – 8.7 million • Size – 1572 km2 • 33 Local Authorities • Elected Mayor with strategic powers over all of Greater London • TfL are the integrated transport authority responsible for delivering the Mayor's strategy and commitments on transport. • On the roads, we regulate taxis and the private hire trade, run the Congestion Charging and Low Emission Zone (LEZ) schemes, manage the city’s 580km red route network, operate all of the Capital’s 6,300 traffic signals • Our operational responsibilities include London Underground, London Buses, Docklands Light Railway, London Overground, TfL Rail, London Trams, London River Services, London Dial-a-Ride, Victoria Coach Station, Santander Cycles and the Emirates Air Line. 3 Timeline of charging schemes in London – February 2003 Congestion Charge Launched – 2008 Low Emission Zone launched – 2012 Low Emission Zone tightened – March 2015 - Ultra Low Emission Zone in central confirmed – May 2016 - Sadiq Khan elected Mayor – October 2017 – T-Charge Launched – November 2017 – ULEZ start date brought forward to April 2019 – December 2017 – Consultation on future expansion of ULEZ and tighter LEZ 4 Congestion Charging Zone 6 Why was Congestion Charging necessary? • Despite 85% public transport usage, vehicular traffic major problem • 185,000 cars entered central London each day • Central London most congested area in UK; traffic speeds <9mph • Congestion persisted throughout the day • Congestion cost London an estimated £4 billion • To address this, an area-based charging scheme was chosen for central London (eligible motorists pay once per day) • Objectives of scheme: - Reduce traffic and traffic congestion - Raise revenue to re-invest in transport. -

Tfl Interchange Signs Standard

Transport for London Interchange signs standard Issue 5 MAYOR OF LONDON Transport for London 1 Interchange signs standard Contents 1 Introduction 3 Directional signs and wayfinding principles 1.1 Types of interchange sign 3.1 Directional signing at Interchanges 1.2 Core network symbols 3.2 Directional signing to networks 1.3 Totem signs 3.3 Incorporating service information 1.3 Horizontal format 3.4 Wayfinding sequence 1.4 Network identification within interchanges 3.5 Accessible routes 1.5 Pictograms 3.6 Line diagrams – Priciples 3.7 Line diagrams – Line representation 3.8 Line diagrams – Symbology 3.9 Platform finders Specific networks : 2 3.10 Platform confirmation signs National Rail 2.1 3.11 Platform station names London Underground 2.2 3.12 Way out signs Docklands Light Railway 2.3 3.13 Multiple exits London Overground 2.4 3.14 Linking with Legible London London Buses 2.5 3.15 Exit guides 2.6 London Tramlink 3.16 Exit guides – Decision points 2.7 London Coach Stations 3.17 Exit guides on other networks 2.8 London River Services 3.18 Signing to bus services 2.9 Taxis 3.19 Signing to bus services – Route changes 2.10 Cycles 3.20 Viewing distances 3.21 Maintaining clear sightlines 4 References and contacts Interchange signing standard Issue 5 1 Introduction Contents Good signing and information ensure our customers can understand Londons extensive public transport system and can make journeys without undue difficulty and frustruation. At interchanges there may be several networks, operators and line identities which if displayed together without consideration may cause confusion for customers. -

The Ultra Low Emission Capital

London: The Ultra Low Emission Capital Go Ultra Low City Scheme Bid 1 Copyright Greater London Authority October 2015 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 3 Contents London’s Go Ultra Low City Scheme Bid 6 Part 2: DELIVERING THE BID Part 1: LONDON’S BID Delivery milestones 74 1.0 Why London? Unlocking the UK’s potential by investing in the capital 11 How London fulfils OLEV’s criteria 76 1.1 Changing infrastructure in residential areas 23 Costs 78 1.2 Changing infrastructure for car clubs 33 Bid partners 84 1.3 Charging infrastructure for commercial fleets 41 State aid 86 1.4 Neighbourhoods of the Future 55 Conclusion 88 PART ONE 5 OVERVIEW 2050. In doing so, we will deliver air quality benefits and will be able to track In July, London set out its vision to progress through our comprehensive become an ultra low emission vehicle emissions monitoring networks and capital. London is bidding for £20 data reporting. million in funding from the Office for Low Emission Vehicles (OLEV) Go Ultra Low London’s bid will overcome the most City Scheme to make this vision a reality. profound barrier to ULEV uptake; the availability of charging infrastructure. This bid builds on the progress made The new delivery partnership for by London’s innovative policies such residential charging addresses barriers as the Congestion Charge and Low for private users, primarily the lack Emission Zone and local councils’ work of off-street parking and related to incentivise cleaner vehicles through complexity of charging. -

Submissions from Rural and Metropolitan Councils

Municipal Association of Victoria Subm ission to the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Com m ittee Inquiry into future oil supply and alternative transport fuels February 2006 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................2 Local Government Context ..........................................................................................2 Options for Reducing Transport Fuel Demand ............................................................3 Encouragement of Alternative Transport Options ....................................................3 Land Use Planning and Transport Options ..............................................................4 Commonwealth Government Support of Public Transport.......................................5 Removal of Taxation Incentive to Consume Petroleum ...........................................6 Alternative Fuel Sources ..............................................................................................7 Government Policy to Promote Alternative Fuel Sources ........................................8 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................9 6 Introduction Local government in Victoria has a significant interest in transport through its direct provision of transport assets, such as roads, and its statutory and strategic land use planning responsibilities. In addition, local government is also -

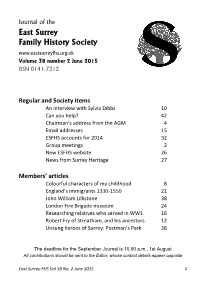

Journal JUN15

Journal of the East Surrey Family History Society www.eastsurreyfhs.org.uk Volume 38 number 2 June 2015 ISSN 0141-7312 Regular and Society items An interview with Sylvia Dibbs 10 Can you help? 42 Chairman’s address from the AGM 4 Email addresses 15 ESFHS accounts for 2014 32 Group meetings 2 New ESFHS website 26 News from Surrey Heritage 27 Members’ articles Colourful characters of my childhood 8 England’s immigrants 1330-1550 21 John William Lillistone 38 London Fire Brigade museum 24 Researching relatives who served in WW1 16 Robert Fry of Streatham, and his ancestors 12 Unsung heroes of Surrey: Postman’s Park 36 The deadline for the September Journal is 10.00 a.m., 1st August All contributions should be sent to the Editor, whose contact details appear opposite East Surrey FHS Vol 38 No. 2 June 2015 1 Group meetings June 4 Surrey Gardens in Walworth 1831 – 1878 Stephen Humphrey Sutton Stephen is a Local and Family Historian in Southwark 8 Had you thought of looking at . ? Hilary Blanford Southwark A look at some unusual sources, and ideas to add some flesh to the bones of your ancestors 16 What did your ancestors leave behind? Croydon This is an open meeting: please bring anything relevant to your family history and share your memorabilia 24 Hearth Tax and other 17th century sources Francis Howcutt Lingfield July 2 My ancestors were Thames watermen Pat Hilbert Sutton Pat has been a family historian for over 20 years and is currently Chairman of the East Dorset group of the Somerset and Dorset FHS. -

Chapter Four – a Good Public Transport Experience

A GOOD PUBLIC TRANSPORT EXPERIENCE 129 Chapter four – A good public transport experience London has one of the most extensive public transport networks in the world, with more than 9 million trips made every day by bus, tram, Tube, train and river boat. Use of the public transport system has increased by 65 per cent since 2000, largely because of enhanced services and an improved customer experience. An easy to use and accessible public transport system is an essential part of the Healthy Streets Approach as it gives people alternatives to car use for journeys that are not possible on foot or by cycle. By providing the most efficient and affordable option for journeys that are either impractical or too long to walk or cycle, public transport has helped to reduce Londoners’ dependency on cars during the past 15 years and this trend must continue. VERSION FOR PUBLICATION A GOOD PUBLIC TRANSPORT EXPERIENCE 131 401 As it grows, the city requires the public This chapter sets out the importance of The whole journey ‘By 2041, the transport capacity to reduce crowding a whole journey approach, where public A good public transport experience and support increasing numbers of transport improvements are an integral means catering for the whole journey, public transport people travelling more actively, efficiently part of delivering the Healthy Streets with all its stages, from its planning to and sustainably. Figure 18 shows that Approach. The chapter then explains the return home. All public transport system will need by 2041 the public transport system will in four sections how London’s public journeys start or finish on foot or by need to cater for up to around 15 million transport services can be improved for cycle, and half of all walking in London is trips every day. -

Sustainable Mobility TII Position Paper

Sustainable Mobility TII Position Paper November 2020 Contents 1 | Introduction 3 2 | Definition of Sustainable Mobility 4 3 | Current Issues 6 3.1 Transport Inequity 6 3.2 Severance and Poor Permeability 6 4 | Vision for Sustainable Mobility 7 4.1 Planning 7 4.2 Multi-Modal Travel 9 4.3 Demand Management 14 4.4 Expanding Data Collection 14 4.5 Collaboration 15 5 | Summary 16 2 1 | Introduction TII’s purpose is to provide sustainable transport infrastructure transport in Ireland. and services, delivering a better quality of life, supporting economic growth and respecting the environment. In fulfilling The purpose of this paper is to outline TII’s position on this purpose, TII strive to be leaders in the delivery and Sustainable Mobility, in terms of: operation of sustainable transport infrastructure and to ensure – The importance of sustainable mobility; that Ireland’s national road and light rail infrastructure is safe and resilient, delivering sustainability mobility for people and – The current issues that need to be overcome to provide for goods. Sustainability is one TII’s core values that permeate sustainable mobility; and our way of working, playing our part in addressing the climate – The vision for what sustainable mobility can be and can and biodiversity crisis. This purpose, vision and value is deliver, and key themes through which it can be achieved. set out in the TII Statement of Strategy 2021 to 2025 which makes an overt commitment to supporting the transition to Sustainable mobility is a complicated, multi-faceted issue a low-carbon and climate resilient future, through enabling and this paper is not intended to address every single active travel and prioritising sustainability in decision making, element of the topic.