TELLING TIME: Reflections on a Life in Music Stanley Walden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baixar Baixar

http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/1984-8951.2012v13n103p32 Anormais na obra fotográfica de Diane Arbus Abnormals in the photographic work of Diane Arbus 1 Daniela Szwertszarf Resumo Este artigo investiga a relação entre a iconografia teratológica e a fotografia artística através da análise da obra fotográfica de Diane Arbus (1923-1971). Seu olhar inovador aborda questões relevantes sobre os novos sentidos do anormal. Nos anos 60, a redefinição dos conceitos de norma e desvio faz o monstro passar da ordem do outro para a ordem do idêntico. As produções teóricas de Michel Foucault, Jean-Jacques Courtine, Erving Goffman e Ieda Tucherman oferecem as ferramentas necessárias para a discussão sobre a obra de Diane Arbus na sua relação com o universo teratológico. Palavras-chave: Fotografia. Monstros. Anormais. Contracultura. Diane Arbus. Abstract This article studies the relation between teratological iconography and artistic photography through an analysis of Diane Arbus’ (1923-1971) photographic work. Her innovative gaze raises relevant questions about the new meanings of the abnormal. In the 60s, the redefinition of norm and deviance concepts turns the monster from the realm of the other to the realm of the identical. Theoretical works of Michel Foucault, Jean-Jacques Courtine, Erving Goffman and Ieda Tucherman offer necessary tools to the discussion of Diane Arbus’ work in relation to the teratological universe. Key words: Photography. Monsters. Abnormals. Counterculture. Diane Arbus. 1 Introdução Neste artigo, procuraremos relacionar o olhar específico de Diane Arbus com o olhar geral dos anos 60 sobre os anormais. No século XIX, as feiras de exibição das monstruosidades viveram o seu apogeu, celebrando o olhar cruel sobre o corpo diferente. -

Grey Lodge Occult Review™

May 1 2003 e.v. Issue #5 Grey Lodge Occult Review™ Gems from the Archives Selections from the archived Web-Material C O N T E N T S Mummeries of Resurrection The Cycle of Osiris in Finnegans Wake by Mark L. Troy The Man Who Invented Flying Saucers by John A. Keel SF, Occult Sciences, and Nazi Myths by Manfred Nagl Exegesis excerpts 1974-1982 "The Ten Major Principles of the Gnostic Revelation" by Philip K. Dick I Understand Philip K. Dick by Terence Mckenna Dr. Green and the Goblins of Langley by Jim Schnabel Brother Dave Morehouse D:.I:.A:. Remote Viewer & NDE Experiencer Excerpt from: Psychic Warrior by David Morehouse The Oberg Files by Blue Resonant Human, Ph.D. (Agent BlueBird) EXIT Communication to all Brethren (Information) from Robert De Grimston The Process - Church of the Final Judgement The Gitanjali or `song offerings' by Rabindranath Tagore with an introduction by William B. Yeats Rosa Alchemica by William B. Yeats (Note: PDF) John Dee by Charlotte Fell-Smith (Note: PDF) Serapis A Romance by Georg Ebers (Note: PDF) Home GLORidx Close Window Except where otherwise noted, Grey Lodge Occult Review™ is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. Grey Lodge Occult Review™ 2003 e.v. - Issue #5 Mummeries of Resurrection The Cycle of Osiris in Finnegans Wake Mark L. Troy Uppsala 1976 Doctoral dissertation at the University of Uppsala 1976 HTML version prepared by Eric Rosenbloom Kirby Mountain Composition & Graphics 2002 Note: Page numbers from the printed text have been retained in the table of contents to use as approximate guides for the references in the bibliographies, line index, and elsewhere. -

Visione Del Mondo

Weltanschauung - Visione del mondo Art Forum Würth Capena 14.09.09 – 07.08.10 Opere e testi di: Kofi Annan, Louise Bourgeois, Abdellatif Laâbi, Imre Bukta, Saul Bellow, John Nixon, Bei Dao, Xu Bing, Branko Ruzic, Richard von Weizsäcker, Anselm Kiefer, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Marcos Benjamin, Twins Seven Seven, Paavo Haavikko, Hic sunt leones, Nelson Mandela, Kyung Hwan Oh, Jean Baudrillard, Huang Yong Ping, Nagib Machfus, Inge Thiess-Böttner, Guido Ceronetti, Richard Long, Yasar Kemal, Igor Kopystiansky, Imre Kertèsz, Svetlana Kopystiansky, Kazuo Katase, Milan Kundera, Frederich William Ayer, Günter Uecker, Durs Grünbein, Mehmed Zaimovic, Enzo Cucchi, Vera Pavlova, Franz-Erhard Walther, Charles D. Simic, Horacio Sapere, Susan Sontag, Hidetoshi Nagasawa, George Steiner, Nicole Guiraud, Bernard Noël, Mattia Moreni, George Tabori, Richard Killeen, Abdourahman A. Waberi, Roser Bru, Doris Runge, Grazina Didelyte, Gérard Titus-Carmel, Edoardo Sanguineti, Mimmo Rotella, Adam Zagajewski, Piero Gilardi, Günter Grass, Anise Koltz, Moritz Ney, Lavinia Greenlaw, Xico Chaves, Liliane Welch, Fátima Martini, Dario Fo, Tom Wesselmann, Ernesto Tatafiore, Emmanuel B. Dongala, Olavi Lanu, Martin Walser, Roman Opalka, Kostas Koutsourelis, Emilio Vedova, Dalai Lama, Gino Gorza, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Robert Indiana, Nadine Gordimer, Efiaimbelo, Les Murray, Arthur Stoll, Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, Boris Orlov, Carlos Fuentes, Klaus Staeck, Alì Renani, Wolfang Leber, Alì Aramideh Ahar, Sogyal Rinpoche, Ulrike Rosembach, Andrea Zanzotto, Adriena Simotova, Jürgen -

Felix Issue 0985, 1994

loo<tF The Student Newspaper of Imperiaiperiall ColleqCollegee I 3DRI8B3iaCE||olrj g 210CT94 TCCB-tSCTIONj enamings benefits of the proposal had not. ANDREW DORMAN-SMITH been adequately debated. Professor Shaw said the name of Senior academics at. the. the Department itself does not Department, of Mineral Resources overly matter, and said he was, Engineering (MRE) have called "a believer in tradition". Professor for further discussions over a plan Shaw would not say if he sup- to rename the department. Earth ported the name change proposal. Resources Engineering has However, the new head of emerged as the favourite choice MRE, and Dean of the newly for a new name, after discussions established Graduate School of between college officials. the Environment, Professor The change has been mooted Woods, is believed to think the following a letter from the proposal is a 'great idea'. His role Professor John Archer, Pro- as Dean will be to coordinate the Rector, which asks for comments departments of Imperial, and to on the new title. Professor Archer, present the benefits for research said that he has received only one of the college in line with a review negative response to his letter, completed in May by Sir John and claimed that most of the Mason. department's staff agree with the The other two RSM depart- proposal. But Professor Archer ments may also change names. said discussions are continuing - The college's chief decision mak- despite the publication of an offi- ing body, the Management cial college note which says the Finnish Embassy Planning Group (MPG), has sug- Photo by Ivan Chan change will take place "shortly". -

Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America

CRUMP, MELANIE AUSTIN. D.M.A. When Words Are Not Enough: Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America. (2008) Directed by Mr. David Holley, 93 pp. Although multiple books and articles expound upon the musical culture and progress of American classical, popular and folk music in the United States, there are no publications that investigate the development of extended vocal techniques (EVTs) throughout twentieth-century American music. Scholarly interest in the contemporary music scene of the United States abounds, but few sources provide information on the exploitation of the human voice for its unique sonic capabilities. This document seeks to establish links and connections between musical trends, major artistic movements, and the global politics that shaped Western art music, with those composers utilizing EVTs in the United States, for the purpose of generating a clearer musicological picture of EVTs as a practice of twentieth-century vocal music. As demonstrated in the connecting of musicological dots found in primary and secondary historical documents, composer and performer studies, and musical scores, the study explores the history of extended vocal techniques and the culture in which they flourished. WHEN WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH: TRACING THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA by Melanie Austin Crump A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ___________________________________ Committee Chair To Dr. Robert Wells, Mr. Randall Outland and my husband, Scott Watson Crump ii APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The School of Music at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

Artist Series – Gilbert Kalish Program Notes

ARTIST SERIES – GILBERT KALISH PROGRAM GEORGE CRUMB (b. 1929) Three Early Songs for Voice and Piano (1947) Night Let It Be Forgotten Wind Elegy Tony Arnold, soprano • Gilbert Kalish, piano FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) “Der Hirt auf dem Felsen” for Soprano, Clarinet, and Piano, D. 965, Op. 129 (1828) Lisette Oropesa, soprano • David Shifrin, clarinet • Gilbert Kalish, piano JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Quartet No. 3 in C minor for Piano, Violin, Viola, and Cello, Op. 60 (1855-56, 1874) Allegro non troppo Scherzo: Allegro Andante Finale: Allegro comodo Gilbert Kalish, piano • Nicolas Dautricourt, violin • Paul Neubauer, viola • Torleif Thedéen, cello NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Three Early Songs for Voice and Piano (1947) George Crumb (b. CHarleston, WV, 1929) Crumb wrote these songs in 1947, the year he graduated high school and entered Mason College in his native Charleston, West Virginia. His now-wife of 70 years, Elizabeth May Brown, was the first to sing them and they are dedicated to her. They are wholly unlike the works that Crumb eventually became famous for—their sound is more early 20th century art song than the unique and otherworldly sound palette he would later develop. Crumb explained that in West Virginia at that time, Debussy was “almost an ultra-modern.” These songs, with delightful melodies and floating harmonies, show that young Crumb, even before finding his mature style, still had a gift for music that is understated yet emotionally powerful. Crumb suppressed the vast majority of his student compositions but he’s allowed performance of these songs. “Most of the music I wrote before the early sixties (when I finally found my own voice) now Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center causes me intense discomfort,” he writes, “although I make an exception for a few songs which I composed when I was 17 or 18.… these little pieces stayed in my memory and when, some years ago, Jan DeGaetani expressed an interest in seeing them (with a view to possible performance if she liked them), I made a few slight revisions and even decided to have them published. -

Sinister Wisdom 70.Pdf

Sinister Sinister Wisdom 70 Wisdom 70 30th Anniversary Celebration Spring 2007 $6$6 US US Publisher: Sinister Wisdom, Inc. Sinister Wisdom 70 Spring 2007 Submission Guidelines Editor: Fran Day Layout and Design: Kim P. Fusch Submissions: See page 152. Check our website at Production Assistant: Jan Shade www.sinisterwisdom.org for updates on upcoming issues. Please read the Board of Directors: Judith K. Witherow, Rose Provenzano, Joan Nestle, submission guidelines below before sending material. Susan Levinkind, Fran Day, Shaba Barnes. Submissions should be sent to the editor or guest editor of the issue. Every- Coordinator: Susan Levinkind thing else should be sent to Sinister Wisdom, POB 3252, Berkeley, CA 94703. Proofreaders: Fran Day and Sandy Tate. Web Design: Sue Lenaerts Submission Guidelines: Please read carefully. Mailing Crew for #68/69: Linda Bacci, Fran Day, Roxanna Fiamma, Submission may be in any style or form, or combination of forms. Casey Fisher, Susan Levinkind, Moire Martin, Stacee Shade, and Maximum submission: five poems, two short stories or essays, or one Sandy Tate. longer piece of up to 2500 words. We prefer that you send your work by Special thanks to: Roxanna Fiamma, Rose Provenzano, Chris Roerden, email in Word. If sent by mail, submissions must be mailed flat (not folded) Jan Shade and Jean Sirius. with your name and address on each page. We prefer you type your work Front Cover Art: “Sinister Wisdom” Photo by Tee A. Corinne (From but short legible handwritten pieces will be considered; tapes accepted the cover of Sinister Wisdom #3, 1977.) from print-impaired women. All work must be on white paper. -

Beverly Hills

briefs • City to subsidize $1.6 million briefs • City refuses to declare rudy cole • My recommendations loan for City Manager housing Page 3 opinion on subway route Page 4 for state office Page 6 ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES Issue 575 • October 7 - October 13, 2010 OUR 11th Beverly Hills’ Anniversary First Lady The Weekly’s interview with Lonnie Delshad cover story • pages 8-9 Few motorists would risk their lives by for anyone but a Democrat because it would briefs • Lively subway route hearing at briefs • Julian Gold announces rudy cole • Roxbury Park Page 2 candidacy for City Council Page 3 United city speaks Page 6 bicycle community in the region, and isn’t have disappointed his liberal mother. As ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com that part of our transportation problem? Too one of my favorite commentators, Dennis letters too few folks using alternate transportation Prager, pointed out in a recent article, so WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES means too many cars on the road. Bike- many registered Democrats vote for Left- Issue 574 • September 30 - October 6, 2010 friendly infrastructure not only protects wing candidates who do not share their Beverly High Athletic cyclists entitled to ride all of the streets in views for purely emotional, nonsensical Alumni to be inducted & email our city, but it reduces motorist liability too. reasons. In Rudy’s case, it is because his Simply put, bikes belong, so let’s plan for mother would disapprove of him voting into Hall of Fame them to accommodate bikes safely. -

George Tabori

George Tabori George Tabori est un artiste accompli, scénariste, romancier, nouvelliste, auteur et metteur en scène de théâtre, directeur, chef de troupe, comé- dien à ses heures, né hongrois le 24 mai 1914 à Budapest, et décédé bri- tannique le 23 juillet 2007 à Berlin, à l’âge de 93 ans. Né en Hongrie en 1914 dans une famille d’intellectuels juifs, György Tábori est envoyé par son père en apprentissage à Berlin en 1932 et 1933. Puis il émigre à Londres en 1935 pour rejoindre son frère aîné. Il adopte la nationalité britannique, devient journaliste à la BBC et traducteur ; d’abord correspondant de guerre en Bulgarie et en Turquie, il s’engage dans l’armée britannique en 1941 et est affecté au Proche-Orient, où il écrit son premier roman. En 1943, il rentre à Londres et travaille de nouveau à la BBC. Ses parents sont déportés. Seule sa mère survit. En 1945, il est invité à Hollywood, son roman ayant attiré l’attention des studios, et s’installe aux États-Unis. Il signe des scénarios de films, notamment pour Alfred Hitchcock (La Loi du silence), Anton Litvak (Le Voyage), Joseph Losey (Cérémonie secrète, seul script qu’il revendique). En dehors de son activité de scénariste qui ne le satisfait pas au point de vue littéraire, il publie des romans. Il fréquente les plus grandes stars hollywoodiennes (Charlie Chaplin, Greta Garbo…) et les intellectuels alle- mands en exil. Assistant de Charles Laughton en 1947, il fait la rencontre décisive de Bertolt Brecht qu’il traduit pour la scène américaine. -

Visualizing Levinas:Existence and Existents Through Mulholland Drive

VISUALIZING LEVINAS: EXISTENCE AND EXISTENTS THROUGH MULHOLLAND DRIVE, MEMENTO, AND VANILLA SKY Holly Lynn Baumgartner A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Kris Blair Don Callen Edward Danziger Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie ii © 2005 Holly Lynn Baumgartner All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor This dissertation engages in an intentional analysis of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’s book Existence and Existents through the reading of three films: Memento (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001), and Mulholland Drive, (2001). The “modes” and other events of being that Levinas associates with the process of consciousness in Existence and Existents, such as fatigue, light, hypostasis, position, sleep, and time, are examined here. Additionally, the most contested spaces in the films, described as a “Waking Dream,” is set into play with Levinas’s work/ The magnification of certain points of entry into Levinas’s philosophy opened up new pathways for thinking about method itself. Philosophically, this dissertation considers the question of how we become subjects, existents who have taken up Existence, and how that process might be revealed in film/ Additionally, the importance of Existence and Existents both on its own merit and to Levinas’s body of work as a whole, especially to his ethical project is underscored. A second set of entry points are explored in the conclusion of this dissertation, in particular how film functions in relation to philosophy, specifically that of Levinas. What kind of critical stance toward film would be an ethical one? Does the very materiality of film, its fracturing of narrative, time, and space, provide an embodied formulation of some of the basic tenets of Levinas’s thinking? Does it create its own philosophy through its format? And finally, analyzing the results of the project yielded far more complicated and unsettling questions than they answered. -

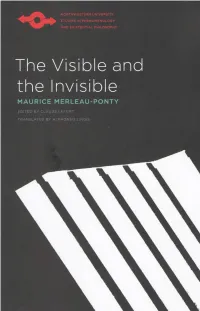

Maurice Merleau-Ponty,The Visible and the Invisible

Northwestern University s t u d i e s i n Phenomenology $ Existential Philosophy GENERAL EDITOR John Wild. ASSOCIATE EDITOR James M. Edie CONSULTING EDITORS Herbert Spiegelberg William Earle George A. Schrader Maurice Natanson Paul Ricoeur Aron Gurwitsch Calvin O. Schrag The Visible and the Invisible Maurice Merleau-Ponty Edited by Claude Lefort Translated by Alphonso Lingis The Visible and the Invisible FOLLOWED BY WORKING NOTES N orthwestern U n i v e r s i t y P r e s s 1968 EVANSTON Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Originally published in French under the title Le Visible et l'invisible. Copyright © 1964 by Editions Gallimard, Paris. English translation copyright © 1968 by Northwestern University Press. First printing 1968. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 15 14 13 12 11 ISBN-13: 978-0-8101-0457-0 isbn-io: 0-8101-0457-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress Permission has been granted to quote from Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes (New York: The Philosophical Library, 1956). @ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence o f Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi Z39.48-1992. Contents Editor’s Foreword / xi Editorial Note / xxxiv T ranslatofs Preface / xl T h e Visib l e a n d t h e In v is ib l e : Philosophical Interrogation i Reflection and Interrogation / 3 a Interrogation and Dialectic / 50 3 Interrogation and Intuition / 105 4 The Intertwining—The Chiasm / 130 5 [a ppen d ix ] Preobjective Being: The Solipsist World / 156 W orking N otes / 165 Index / 377 Chronological Index to Working Notes / 279 Editor's Foreword How eve r e x p e c t e d it may sometimes be, the death of a relative or a friend opens an abyss before us. -

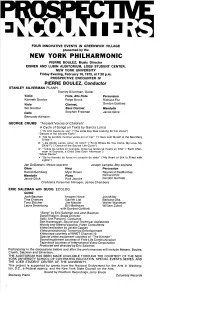

Prospective Encounters

FOUR INNOVATIVE EVENTS IN GREENWICH VILLAGE presented by the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PIERRE BOULEZ, Music Director EISNER AND LUBIN AUDITORIUM, LOEB STUDENT CENTER, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Friday Evening, February 18, 1972, at 7:30 p.m. PROSPECTIVE ENCOUNTER IV PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor STANLEY SILVERMAN PLANH Stanley Silverman, Guitar Violin Flute, Alto Flute Percussion Kenneth Gordon Paige Brook Richard Fitz Viola Clarinet, Gordon Gottlieb Sol Greitzer Bass Clarinet Mandolin Cello Stephen Freeman Jacob Glick Bernardo Altmann GEORGE CRUMB "Ancient Voices of Children" A Cycle of Songs on Texts by Garcia Lorca I "El niho busca su voz" ("The Little Boy Was Looking for his Voice") "Dances of the Ancient Earth" II "Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar" ("I Have Lost Myself in the Sea Many Times") III "6De d6nde vienes, amor, mi nino?" ("From Where Do You Come, My Love, My Child?") ("Dance of the Sacred Life-Cycle") IV "Todas ]as tardes en Granada, todas las tardes se muere un nino" ("Each After- noon in Granada, a Child Dies Each Afternoon") "Ghost Dance" V "Se ha Ilenado de luces mi coraz6n de seda" ("My Heart of Silk Is Filled with Lights") Jan DeGaetani, Mezzo-soprano Joseph Lampke, Boy soprano Oboe Harp Percussion Harold Gomberg Myor Rosen Raymond DesRoches Mandolin Piano Richard Fitz Jacob Glick PaulJacobs Gordon Gottlieb Orchestra Personnel Manager, James Chambers ERIC SALZMAN with QUOG ECOLOG QUOG Josh Bauman Imogen Howe Jon Miller Tina Chancey Garrett List Barbara Oka Tony Elitcher Jim Mandel Walter Wantman Laura Greenberg Bill Matthews