Cinderella Tales and Their Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Guide for Teachers and Students

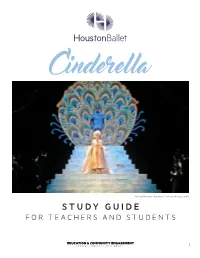

Melody Mennite in Cinderella. Photo by Amitava Sarkar STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRE AND POST-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES AND INFORMATION Learning Outcomes & TEKS 3 Attending a ballet performance 5 The story of Cinderella 7 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Choreographer 11 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Composer 12 The Artists who Created Cinderella Designer 13 Behind the Scenes: “The Step Family” 14 TEKS ADDRESSED Cinderella: Around the World 15 Compare & Contrast 18 Houston Ballet: Where in the World? 19 Look Ma, No Words! Storytelling in Dance 20 Storytelling Without Words Activity 21 Why Do They Wear That?: Dancers’ Clothing 22 Ballet Basics: Positions of the Feet 23 Ballet Basics: Arm Positions 24 Houston Ballet: 1955 to Today 25 Appendix A: Mood Cards 26 Appendix B: Create Your Own Story 27 Appendix C: Set Design 29 Appendix D: Costume Design 30 Appendix E: Glossary 31 2 LEARNING OUTCOMES Students who attend the performance and utilize the study guide will be able to: • Students can describe how ballets tell stories without words; • Compare & contrast the differences between various Cinderella stories; • Describe at least one dance from Cinderella in words or pictures; • Demonstrate appropriate audience behavior. TEKS ADDRESSED §117.106. MUSIC, ELEMENTARY (5) Historical and cultural relevance. The student examines music in relation to history and cultures. §114.22. LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH LEVELS I AND II (4) Comparisons. The student develops insight into the nature of language and culture by comparing the student’s own language §110.25. ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS AND READING, READING (9) The student reads to increase knowledge of own culture, the culture of others, and the common elements of cultures and culture to another. -

Racing Australia Limited

5 RANSOM TRUST (9)57½ WELLO'S PLUMBING CLASS 1 HANDICAP Owner: Mrs V L Klaric & I Cajkusic 1 4yo ch m Trust in a Gust - Love for Ransom (Red Ransom (USA)) KAYLA NISBET 1000 METRES 1.10 P.M. BLACK, GOLD MALTESE CROSS AND SEAMS, BLACK CAP Of $24,000.1st $12,280, 2nd $4,440, 3rd $2,300, 4th $1,200, 5th $750, 6th $550, 7th (W) 8 Starts. 1-0-1 $51,012 TECHFORM Rating 95 ' $500, 8th $500, 9th $500, 10th $500, Equine Welfare Fund $240, Jockey Welfare Fund Josh Julius (Bendigo) $240, Class 1, Handicap, Minimum Weight 55kg, Apprentices can claim, BOBS Silver Dist: 2:0-0-1 Wet: 3:1-0-1 Bonus Available Up To $9625, Track Name: Main Track Type: Turf 4-11 WOD 27Nov20 1100m BM64 Good3 H Coffey(4) 56 $10 This Skilled Cat 60 RECORD: 950 0-57.60 Emerging Power 1.0L, 1:04.30 5-12 ECHA 31Dec20 1200m BM58 Good4 D Stackhouse(1) 58.5 $4.60 Diamond FLYING FINCH (1) 61 Thora 59.5 3.2L, 1:10.75 1 9-10 BLLA 19Jan21 1112m BM58 Good3 M Walker(10) 60 $6 Arigato 61 9.8L, Owner: Dr C P Duddy & R A Osborne 1:05.10 5yo b or br g Redente - Lim's Falcon (Fasliyev (USA)) 3-8 COLR 05Aug21 1000m BM64 Soft7 D Bates(4) 56 $31 Bones 60.5 2.5L, MICHAEL TRAVERS 0:59.88 LIME, PALE BLUE YOKE, YELLOW SASH 10-11 MORP 21Aug21 1050m NMW BM70 Soft6 J Eaton(1) 54 $21 Lohn Ranger 54.5 (DW) 7 Starts. -

Charles Perrault Was Born More Than 300 Years Ago, in 1628. He Wrote

Charles Perrault was born more than 300 years ago, in 1628. He wrote many books, but he will be remembered forever for just one: Stories or Tales from Times Past, with Morals: Tales of Mother Goose. The book contained only eight fairy tales, and they have become classics around the world. You have probably heard some of these stories in your own life! Sleeping Beauty Little Red Riding Hood Blue Beard Puss in Boots The Fairiesj Cinderella Ricky with the Tuft Little Tom Thumby Many of these stories were already well-known to people even in Charles Perrault’s time, but they had never been written down. They were stories told orally (which means spoken out loud), around the fire or at bedtime, to entertain and teach children. Some stories that Perrault wrote down were popular all over Europe, and some were also written down later in Germany as Grimm Fairy Tales. If it were not for writers like Charles Perrault, many of these stories would have been lost to us. What’s even better is that he wrote them with such style and wit. PerraultFairyTales.com is proud to bring them into the computer age! Charles Perrault was born to a wealthy family in Paris, France. He was always interested in learning. He went to the best schools, where he was always top of his class. When he grew up, Charles Perrault got married and became a lawyer. He also worked with his brother collecting taxes for the city of Paris. He was always ahead of his time, and caused a stir for writing that modern ideas are better than ancient ideas. -

Perrault : Cendrillon Ou La Petite Pantoufle De Verre (1697) Source : Charles Perrault, Les Contes De Perrault, Édition Féron, Casterman, Tournai, 1902

Französisch www.französisch-bw.de Perrault : Cendrillon ou la petite pantoufle de verre (1697) Source : Charles Perrault, Les Contes de Perrault, édition Féron, Casterman, Tournai, 1902 Il était une fois un gentilhomme1 qui épousa, en secondes noces2, une femme, la plus hautaine3 et la plus fière qu’on eût jamais vue. Elle avait deux filles de son humeur, et qui lui ressemblaient en toutes choses. Le mari avait, de son côté, une jeune fille, mais d’une douceur et d’une bonté sans exemple : elle tenait cela de sa mère, qui était la meilleure personne du monde. 5 Les noces ne furent pas plus tôt faites que la belle-mère4 fit éclater sa mauvaise humeur : elle ne put souffrir les bonnes qualités de cette jeune enfant, qui rendaient ses filles encore plus haïssables5. Elle la chargea des plus viles6 occupations de la maison : c’était elle qui nettoyait la vaisselle et les montées7, qui frottait la chambre de Madame et celles de Mesdemoiselles ses filles ; elle couchait tout au haut de la maison, dans un grenier8, sur une méchante paillasse9, pendant que ses sœurs étaient dans des chambres 10 parquetées10 où elles avaient des lits des plus à la mode, et des miroirs où elles se voyaient depuis les pieds jusqu’à la tête. La pauvre fille souffrait tout avec patience et n’osait s’en plaindre à son père, qui l’aurait grondée, parce que sa femme le gouvernait entièrement. Lorsqu’elle avait fait son ouvrage11, elle s’allait mettre au coin de la cheminée, et s’asseoir dans les cendres, ce qui faisait qu’on l’appelait communément dans le logis12 Culcendron. -

As Transformações Nos Contos De Fadas No Século Xx

DE REINOS MUITO, MUITO DISTANTES PARA AS TELAS DO CINEMA: AS TRANSFORMAÇÕES NOS CONTOS DE FADAS NO SÉCULO XX ● FROM A LAND FAR, FAR AWAY TO THE BIG SCREEN: THE CHANGES IN FAIRY TALES IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Paulo Ailton Ferreira da Rosa Junior Instituto Federal Sul-rio-grandense, Brasil RESUMO | INDEXAÇÃO | TEXTO | REFERÊNCIAS | CITAR ESTE ARTIGO | O AUTOR RECEBIDO EM 24/05/2016 ● APROVADO EM 28/09/2016 Abstract This work it is, fundamentally, a comparison between works of literature with their adaptations to Cinema. Besides this, it is a critical and analytical study of the changes in three literary fairy tales when translated to Walt Disney's films. The analysis corpus, therefore, consists of the recorded texts of Perrault, Grimm and Andersen in their bibliographies and animated films "Cinderella" (1950), "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" (1937) and "The little Mermaid "(1989) that they were respectively inspired. The purpose of this analysis is to identify what changes happened in these adapted stories from literature to film and discuss about them. Resumo Este trabalho trata-se, fundamentalmente, de uma comparação entre obras da Literatura com suas respectivas adaptações para o Cinema. Para além disto, é um estudo crítico e analítico das transformações em três contos de fadas literários quando transpostos para narrativas fílmicas de Walt Disney. O corpus de análise, para tanto, é composto pelos textos registrados de Perrault, Grimm e Andersen em suas respectivas bibliografias e os filmes de animação “Cinderella” (1950), “Branca de Neve e os Sete Anões” (1937) e “A Pequena Sereia” (1989) que eles respectivamente inspiraram. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

Connection/Separation

Friday, February 12, 2021 | 4 PM MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC OPERA THEATRE Tazewell Thompson, Director of Opera Studies presents Connection/Separation Featuring arias and scenes from Carmen, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte, La clemenza di Tito, L’elisir d’amore, Le nozze di Figaro, Les pêcheurs de perles, and Lucio Silla A. Scott Parry, Director MSM Opera Theatre productions are made possible by the Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation and the Joseph F. McCrindle Endowment for Opera Productions at Manhattan School of Music. Friday, February 12, 2021 | 4 PM MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC OPERA THEATRE Tazewell Thompson, Director of Opera Studies presents Connection/Separation Featuring arias and scenes from Carmen, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte, La clemenza di Tito, L’elisir d’amore, Le nozze di Figaro, Les pêcheurs de perles, and Lucio Silla A. Scott Parry, Director Myra Huang, Vocal Coach & Pianist Kristen Kemp, Vocal Coach & Pianist Megan P. G. Kolpin, Props Coordinator DIRECTOR’S NOTE In each of our lives—during this last year especially—we may have discovered ourselves in moments of wanting, even needing some sort of human connection, but instead finding separation by any number of barriers. In the arias and scenes that follow, we witness characters in just this kind of moment; searching for meaningful contact yet being somehow barred from achieving it. Through circumstance, distance, convention, misunderstanding, pride, fear, ego, or what have you, we may find ourselves in situations similar to the characters in this program, while looking forward to the days when connection can be more easily achieved and separation the exception to the rule. -

A Genre Is a Conventional Response to a Rhetorical Situation That Occurs Fairly Often

What is a genre? A genre is a conventional response to a rhetorical situation that occurs fairly often. Conventional does not necessarily mean boring. Instead, it means a recognizable pattern for providing specific kinds of information for an identifiable audience demanded by circumstances that come up again and again. For example, new movies open almost every week. Movie makers pay for advertising to entice viewers to see their movies. Genres have a purpose. While consumers may learn about a movie from the ads, they know they are getting a sales pitch with that information, so they look for an outside source of information before they spend their money. Movie reviews provide viewers with enough information about the content and quality of a film to help them make a decision, without ruining it for them by giving away the ending. Movie reviews are the conventional response to the rhetorical situation of a new film opening. Genres have a pattern. The movie review is conventional because it follows certain conventions, or recognized and accepted ways of giving readers information. This is called a move pattern. Here are the moves associated with that genre: 1. Name of the movie, director, leading actors, Sometimes, the opening also includes the names of people and companies associated with the film if that information seems important to the reader: screenwriter, animators, special effects, or other important aspects of the film. This information is always included in the opening lines or at the top of the review. 2. Graphic design elements---usually, movie reviews include some kind of art or graphic taken from the film itself to call attention to the review and draw readers into it. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE ARQUITETURA E URBANISMO O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA Aline Stefânia Zim Brasília - DF 2018 1 ALINE STEFÂNIA ZIM O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Doutora em Arquitetura. Área de Pesquisa: Teoria, História e Crítica da Arte Orientador: Prof. Dr. Flávio Rene Kothe Brasília – DF 2018 2 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ALINE STEFÂNIA ZIM O ALTO E O BAIXO DA ARQUITETURA Tese aprovada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Doutora pelo Programa de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de Brasília. Comissão Examinadora: ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Flávio René Kothe (Orientador) Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo – FAU-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Fernando Freitas Fuão Departamento de Teoria, História e Crítica da Arquitetura – FAU-UFRGS ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dra. Lúcia Helena Marques Ribeiro Departamento de Teoria Literária e Literatura – TEL-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dra. Ana Elisabete de Almeida Medeiros Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo – FAU-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Benny Schvarsberg Departamento de Projeto e Planejamento – FAU-UnB Brasília – DF 2018 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a todos que compartilharam de alguma forma esse manifesto. Aos familiares que não puderam estar presentes, agradeço a confiança e o respeito. Aos amigos, colegas e alunos que dividiram as inquietações e os dias difíceis, agradeço a presença. Aos que não puderam estar presentes, agradeço a confiança. Aos professores, colegas e amigos do Núcleo de Estética, Hermenêutica e Semiótica. -

Le Nucléaire Est Toujours En Course

BCN: record POLITIQUE en 2006 DAVID MARCHON Les libéraux s’associent au référendum UDC contre l’éligibilité des étrangers au plan communal. >>> PAGE 5 KEYSTONE JA 2002 NEUCHÂTEL La Banque cantonale neu- châteloise versera 20 des 30 millions de francs de bénéfice net qu’elle a réa- lisés à l’Etat de Neuchâtel. 0 Jeudi 22 février 2007 ● www.lexpress.ch ● N 44 ● CHF 2.– / € 1.30 >>> PAGE 7 HOCKEY SUR GLACE Neuchâtel YS: Le nucléaire est au tour de Verbier toujours en course ARCHIVES DAVID MARCHON Les hommes d’Alain Pivron s’attaquent dès ce soir aux demi-finales des play-off. Verbier, qui se dresse sur leur route, ne paraît pas en mesure d’empêcher les Neuchâtelois de parvenir en finale. Toutefois, le mentor des «orange et noir» ne fanfaronne pas. Pour l’instant, il ne veut pas parler de promotion. >>> PAGE 20 NEUCHÂTEL Haïr les spots, ça coûte KEYSTONE ÉNERGIE Face à la pénurie qui se dessine vers 2020, le Conseil fédéral propose une quadruple stratégie: utilisation économe, énergies renouvelables, centrales à gaz et maintien de l’option nucléaire – ici la centrale de Leibstadt. >>> PAGE 25 CAISSE-MALADIE Des priorités au moins apparentes Une exclue DAVID MARCHON Economies d’énergie, davantage pénurie est bien attendue pour 2020, il Mauvaise surprise pour les 140 opposants aux d’énergies renouvelables, option reste huit ans pour relever le défi. témoigne de projecteurs de la Maladière: ils ont appris mardi que nucléaire maintenue, recours Malheureusement, les économies leurs démarches pouvaient leur coûter jusqu’à 600 temporaire à des centrales à gaz.