View Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond

cells Review Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond Sarah Kuhn y, Laura Gritti y, Daniel Crooks and Yvonne Dombrowski * Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (L.G.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0044-28-9097-6127 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 7 November 2019; Published: 12 November 2019 Abstract: Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS) that are generated from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC). OPC are distributed throughout the CNS and represent a pool of migratory and proliferative adult progenitor cells that can differentiate into oligodendrocytes. The central function of oligodendrocytes is to generate myelin, which is an extended membrane from the cell that wraps tightly around axons. Due to this energy consuming process and the associated high metabolic turnover oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to cytotoxic and excitotoxic factors. Oligodendrocyte pathology is therefore evident in a range of disorders including multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Deceased oligodendrocytes can be replenished from the adult OPC pool and lost myelin can be regenerated during remyelination, which can prevent axonal degeneration and can restore function. Cell population studies have recently identified novel immunomodulatory functions of oligodendrocytes, the implications of which, e.g., for diseases with primary oligodendrocyte pathology, are not yet clear. Here, we review the journey of oligodendrocytes from the embryonic stage to their role in homeostasis and their fate in disease. We will also discuss the most common models used to study oligodendrocytes and describe newly discovered functions of oligodendrocytes. -

Neuregulin 1–Erbb2 Signaling Is Required for the Establishment of Radial Glia and Their Transformation Into Astrocytes in Cerebral Cortex

Neuregulin 1–erbB2 signaling is required for the establishment of radial glia and their transformation into astrocytes in cerebral cortex Ralf S. Schmid*, Barbara McGrath*, Bridget E. Berechid†, Becky Boyles*, Mark Marchionni‡, Nenad Sˇ estan†, and Eva S. Anton*§ *University of North Carolina Neuroscience Center and Department of Cell and Molecular Physiology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; †Department of Neurobiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510; and ‡CeNes Pharamceuticals, Inc., Norwood, MA 02062 Communicated by Pasko Rakic, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, January 27, 2003 (received for review December 12, 2002) Radial glial cells and astrocytes function to support the construction mine whether NRG-1-mediated signaling is involved in radial and maintenance, respectively, of the cerebral cortex. However, the glial cell development and differentiation in the cerebral cortex. mechanisms that determine how radial glial cells are established, We show that NRG-1 signaling, involving erbB2, may act in maintained, and transformed into astrocytes in the cerebral cortex are concert with Notch signaling to exert a critical influence in the not well understood. Here, we show that neuregulin-1 (NRG-1) exerts establishment, maintenance, and appropriate transformation of a critical role in the establishment of radial glial cells. Radial glial cell radial glial cells in cerebral cortex. generation is significantly impaired in NRG mutants, and this defect can be rescued by exogenous NRG-1. Down-regulation of expression Materials and Methods and activity of erbB2, a member of the NRG-1 receptor complex, leads Clonal Analysis to Study NRG’s Role in the Initial Establishment of to the transformation of radial glial cells into astrocytes. -

Pre-Oligodendrocytes from Adult Human CNS

The Journal of Neuroscience, April 1992, 12(4): 1538-l 547 Pre-Oligodendrocytes from Adult Human CNS Regina C. Armstrong,lJ Henry H. Dorn, l,b Conrad V. Kufta,* Emily Friedman,3 and Monique E. Dubois-Dalcq’ ‘Laboratory of Viral and Molecular Pathogenesis, and %urgical Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland 20892 and 3Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-3246 CNS remyelination and functional recovery often occur after Rapid and efficient neurotransmission is dependent upon the experimental demyelination in adult rodents. This has been electrical insulating capacity of the myelin sheath around axons attributed to the ability of mature oligodendrocytes and/or (reviewed in Ritchie, 1984a,b). Nerve conduction is impaired their precursor cells to divide and regenerate in response after loss of the myelin sheath and results in severe neurological to signals in demyelinating lesions. To determine whether dysfunction in human demyelinating diseases such as multiple oligodendrocyte precursor cells exist in the adult human sclerosis (MS). Remyelination can occur in the CNS of MS CNS, we have cultured white matter from patients under- patients but appears to be limited (Perier and Gregoire, 1965; going partial temporal lobe resection for intractable epilep- Prineas et al., 1984). Studies of acute MS cases have revealed sy. These cultures contained a population of process-bear- that recent demyelinating lesions can exhibit remyelination that ing cells that expressed antigens recognized by the 04 appears to correlate with the generation of new oligodendrocytes monoclonal antibody, but these cells did not express galac- (Prineas et al., 1984; Raine et al., 1988). -

A System for Studying Mechanisms of Neuromuscular Junction Development and Maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2016) 143, 2464-2477 doi:10.1242/dev.130278 TECHNIQUES AND RESOURCES RESEARCH ARTICLE A system for studying mechanisms of neuromuscular junction development and maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R. Gomes1,3,*,‡ ABSTRACT different animal models and cell lines (Chen et al., 2014; Corti et al., The neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a cellular synapse between a 2012; Lenzi et al., 2015) with the hope of recapitulating some motor neuron and a skeletal muscle fiber, enables the translation of features of neuromuscular diseases and understanding the triggers chemical cues into physical activity. The development of this special of one of their common hallmarks: the disruption of the structure has been subject to numerous investigations, but its neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The NMJ is one of the most complexity renders in vivo studies particularly difficult to perform. studied synapses. It is formed of three key elements: the lower motor In vitro modeling of the neuromuscular junction represents a powerful neuron (the pre-synaptic compartment), the skeletal muscle (the tool to delineate fully the fine tuning of events that lead to subcellular post-synaptic compartment) and the Schwann cell (Sanes and specialization at the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic sites. Here, we Lichtman, 1999). The NMJ is formed in a step-wise manner describe a novel heterologous co-culture in vitro method using rat following a series of cues involving these three cellular components spinal cord explants with dorsal root ganglia and murine primary and its role is basically to ensure the skeletal muscle functionality. -

Myelin Biogenesis Is Associated with Pathological Ultrastructure That Is

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.02.429485; this version posted February 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Myelin biogenesis is associated with pathological ultrastructure that 2 is resolved by microglia during development 3 4 5 Minou Djannatian1,2*, Ulrich Weikert3, Shima Safaiyan1,2, Christoph Wrede4, Cassandra 6 Deichsel1,2, Georg Kislinger1,2, Torben Ruhwedel3, Douglas S. Campbell5, Tjakko van Ham6, 7 Bettina Schmid2, Jan Hegermann4, Wiebke Möbius3, Martina Schifferer2,7, Mikael Simons1,2,7* 8 9 1Institute of Neuronal Cell Biology, Technical University Munich, 80802 Munich, Germany 10 2German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), 81377 Munich, Germany 11 3Max-Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine, 37075 Göttingen, Germany 12 4Institute of Functional and Applied Anatomy, Research Core Unit Electron Microscopy, 13 Hannover Medical School, 30625, Hannover, Germany 14 5Department of Neuronal Remodeling, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kyoto 15 University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan. 16 6Department of Clinical Genetics, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, 3015 CN, 17 the Netherlands 18 7Munich Cluster of Systems Neurology (SyNergy), 81377 Munich, Germany 19 20 *Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] 21 Keywords 22 Myelination, degeneration, phagocytosis, microglia, oligodendrocytes, phosphatidylserine 23 24 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.02.429485; this version posted February 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

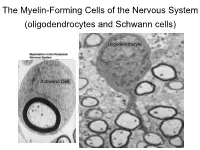

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Tecnicas Microscopicas

CAP 1: TÉCNICAS MICROSCÓPICAS TÉCNICAS MICROSCÓPICAS 11 Lic. Carlos R. Neira Montoya Lic. Eduardo Sedano Gelvet Lic. María Elena Vilcarromero V. El estudio de los tejidos tal como los observamos hoy en día no sería posible sin la ayuda de la histotecnología; esta disciplina se encarga del estudio de los métodos técnicas y procedimientos que permiten la transformación de un órgano en una película lo suficientemente transparente y contrastada que nos permite su observación a través del microscopio (Fig. 1-1). Para que esto ocurra se tiene que seguir una serie de pasos. Cada uno de estos pasos permite la observación de las características morfológicas del tejido que nos indica la normalidad o la alteración patológica; sin embargo en estudios mucho más minuciosos, estos pasos se harán en función de las estructuras o sustancias que se deseen investigar en la muestra correspondiente. Figura 1-1. Un órgano es transformado en una película transparente. - Pág. 5 - CAP 1: TÉCNICAS MICROSCÓPICAS Los pasos de las técnicas microscópicas para obtener un preparado histológico permanente (láminas) son: 1. Toma de la muestra. 2. Fijación. 3. Inclusión. 4. Microtomía. 5. Coloración. 1. TOMA DE LA MUESTRA Es el momento que se selecciona el órgano o tejido a estudiar. De tres fuentes puede provenir el material humano: las necropsias, las biopsias y las piezas operadas. De éstas, sólo la primera puede darnos material normal; las dos últimas habitualmente proporcionarán tejidos para estudio histopatológico. - Necropsias: son las piezas que se obtienen de un cadáver. Para histología normal es necesario que se trate de un cadáver fresco y que no haya sido atacado por ninguna lesión, por lo menos el órgano que se quiere estudiar. -

Nomina Histologica Veterinaria, First Edition

NOMINA HISTOLOGICA VETERINARIA Submitted by the International Committee on Veterinary Histological Nomenclature (ICVHN) to the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists Published on the website of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists www.wava-amav.org 2017 CONTENTS Introduction i Principles of term construction in N.H.V. iii Cytologia – Cytology 1 Textus epithelialis – Epithelial tissue 10 Textus connectivus – Connective tissue 13 Sanguis et Lympha – Blood and Lymph 17 Textus muscularis – Muscle tissue 19 Textus nervosus – Nerve tissue 20 Splanchnologia – Viscera 23 Systema digestorium – Digestive system 24 Systema respiratorium – Respiratory system 32 Systema urinarium – Urinary system 35 Organa genitalia masculina – Male genital system 38 Organa genitalia feminina – Female genital system 42 Systema endocrinum – Endocrine system 45 Systema cardiovasculare et lymphaticum [Angiologia] – Cardiovascular and lymphatic system 47 Systema nervosum – Nervous system 52 Receptores sensorii et Organa sensuum – Sensory receptors and Sense organs 58 Integumentum – Integument 64 INTRODUCTION The preparations leading to the publication of the present first edition of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria has a long history spanning more than 50 years. Under the auspices of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists (W.A.V.A.), the International Committee on Veterinary Anatomical Nomenclature (I.C.V.A.N.) appointed in Giessen, 1965, a Subcommittee on Histology and Embryology which started a working relation with the Subcommittee on Histology of the former International Anatomical Nomenclature Committee. In Mexico City, 1971, this Subcommittee presented a document entitled Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft as a basis for the continued work of the newly-appointed Subcommittee on Histological Nomenclature. This resulted in the editing of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft II (Toulouse, 1974), followed by preparations for publication of a Nomina Histologica Veterinaria. -

Specific Labeling of Synaptic Schwann Cells Reveals Unique Cellular And

RESEARCH ARTICLE Specific labeling of synaptic schwann cells reveals unique cellular and molecular features Ryan Castro1,2,3, Thomas Taetzsch1,2, Sydney K Vaughan1,2, Kerilyn Godbe4, John Chappell4, Robert E Settlage5, Gregorio Valdez1,2,6* 1Department of Molecular Biology, Cellular Biology, and Biochemistry, Brown University, Providence, United States; 2Center for Translational Neuroscience, Robert J. and Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science and Brown Institute for Translational Science, Brown University, Providence, United States; 3Neuroscience Graduate Program, Brown University, Providence, United States; 4Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at Virginia Tech Carilion, Roanoke, United States; 5Department of Advanced Research Computing, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, United States; 6Department of Neurology, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, United States Abstract Perisynaptic Schwann cells (PSCs) are specialized, non-myelinating, synaptic glia of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), that participate in synapse development, function, maintenance, and repair. The study of PSCs has relied on an anatomy-based approach, as the identities of cell-specific PSC molecular markers have remained elusive. This limited approach has precluded our ability to isolate and genetically manipulate PSCs in a cell specific manner. We have identified neuron-glia antigen 2 (NG2) as a unique molecular marker of S100b+ PSCs in skeletal muscle. NG2 is expressed in Schwann cells already associated with the NMJ, indicating that it is a marker of differentiated PSCs. Using a newly generated transgenic mouse in which PSCs are specifically labeled, we show that PSCs have a unique molecular signature that includes genes known to play critical roles in *For correspondence: PSCs and synapses. These findings will serve as a springboard for revealing drivers of PSC [email protected] differentiation and function. -

ARIA Is Concentrated in Nerve Terminals at Neuromuscular Junctions and at Other Synapses

The Journal of Neuroscience, September 1995, 15(g): 6124-6136 ARIA Is Concentrated in Nerve Terminals at Neuromuscular Junctions and at Other Synapses Alfred W. Sandrock, Jr.,i,2 Andrew D. J. Goodearl,’ Qin-Wei Yin,’ David Chang,3 and Gerald D. Fischbachl ‘Department of Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, “Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hosoital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114, and 3Amgen, Inc., Thousand Oaks, California 91320 Skeletal muscle ACh receptors (AChRs) accumulate at neu- natal maturation of AChRs at the neuromuscular junction, which romuscular junctions (nmjs) at least partly because of the results in the replacement of y-subunit-containing receptors with selective induction of AChR subunit genes in subsynaptic those containing E- subunits (Brenner and Sakmann, 1978; Bren- myotube nuclei by the motor nerve terminal. Additionally, ner et al., 1990; Martinou and Merlie, 1991). ARIA (for ACh mammalian AChRs undergo a postnatal change in subunit receptor inducing activity), which was purified from chicken composition from embryonic (cw.&S) to adult (@eS) brains based on its ability to stimulate the synthesis of AChRs forms, a switch that also depends on innervation. ARIA, a in skeletal muscle (Falls et al., 1993), may mediate the ability protein purified from chicken brains based on its ability to of the motor neuron to orchestrate these developmental events. induce AChR synthesis in primary chick muscle cells, is a ARIA mRNA is concentrated in chick and rat motor neurons strong candidate for being the molecule responsible for (Falls et al., 1993; Corfas et al., 1995), and, in both species, is these early developmental events. -

Microglia Activation Triggers Astrocyte-Mediated Modulation of Excitatory Neurotransmission

Microglia activation triggers astrocyte-mediated PNAS PLUS modulation of excitatory neurotransmission Olivier Pascuala,b,c,1,2, Sarrah Ben Achoura,b,c,2, Philippe Rostainga,b,c, Antoine Trillera,b,c, and Alain Bessisa,b,c aInstitut de Biologie de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure, F-75005 Paris, France; bInstitut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale U1024, F-75005 Paris, France; and cCentre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Mixte de Recherche 8197, F-75005 Paris, France Edited* by Tullio Pozzan, University of Padova, Padua, Italy, and approved November 21, 2011 (received for review July 18, 2011) Fine control of neuronal activity is crucial to rapidly adjust to subtle tatively able to sense neuronal activity and/or communicate with changes of the environment. This fine tuning was thought to be astrocytes. In response to stimuli, microglia are activated, and they purely neuronal until the discovery that astrocytes are active players release neurotransmitters (19), which are small molecules such as of synaptic transmission. In the adult hippocampus, microglia are nitric oxide, trophic factors, or cytokines, all known to control the other major glial cell type. Microglia are highly dynamic and neuronal function and synaptic transmission (20, 21). In addition, closely associated with neurons and astrocytes. They react rapidly to changes in plasticity and neuronal activity have been shown to modifications of their environment and are able to release mole- modify the resident time of microglia processes at synapses (22). cules known to control neuronal function and synaptic transmission. Although long-term effects of microglial activation and in- Therefore, microglia display functional features of synaptic part- flammation have been studied (14, 23, 24), early consequences of ners, but their involvement in the regulation of synaptic trans- such activation are still unknown, especially the cell type involved mission has not yet been addressed. -

Human Ipsc-Derived Microglia Assume a Primary Microglia-Like State After Transplantation Into the Neonatal Mouse Brain

Human iPSC-derived microglia assume a primary microglia-like state after transplantation into the neonatal mouse brain Devon S. Svobodaa, M. Inmaculada Barrasaa,b, Jian Shua,c, Rosalie Rietjensa, Shupei Zhanga, Maya Mitalipovaa, Peter Berubec, Dongdong Fua, Leonard D. Shultzd, George W. Bella,b, and Rudolf Jaenischa,e,1 aWhitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA 02142; bBioinformatics and Research Computing, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA 02142; cBroad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA 02142; dThe Jackson Laboratory Cancer Center, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME 04609; and eDepartment of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02142 Contributed by Rudolf Jaenisch, October 16, 2019 (sent for review August 8, 2019; reviewed by Valentina Fossati and Helmut Kettenmann) Microglia are essential for maintenance of normal brain function, Despite these innovations, there are important limitations to with dysregulation contributing to numerous neurological dis- modeling human disease with hiPSC-derived iMGs. As immune eases. Protocols have been developed to derive microglia-like cells cells, microglia are prone to activation and highly sensitive to from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs). However, in vitro culture, which introduces impediments in extending re- primary microglia display major differences in morphology and sults obtained with cultured cells to disease states. This is high- gene expression when grown in culture, including down- lighted by recent studies showing that primary microglia directly regulation of signature microglial genes. Thus, in vitro differenti- isolated from the brain exhibit significant changes in gene ex- ated microglia may not accurately represent resting primary pression when grown in culture for as little as 6 h (26, 27).