Pre-Oligodendrocytes from Adult Human CNS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nervous Tissue

Nervous Tissue Prof.Prof. ZhouZhou LiLi Dept.Dept. ofof HistologyHistology andand EmbryologyEmbryology Organization:Organization: neuronsneurons (nerve(nerve cells)cells) neuroglialneuroglial cellscells Function:Function: Ⅰ Neurons 1.1. structurestructure ofof neuronneuron somasoma neuriteneurite a.a. dendritedendrite b.b. axonaxon 1.11.1 somasoma (1)(1) nucleusnucleus LocatedLocated inin thethe centercenter ofof soma,soma, largelarge andand palepale--stainingstaining nucleusnucleus ProminentProminent nucleolusnucleolus (2)(2) cytoplasmcytoplasm (perikaryon)(perikaryon) a.a. NisslNissl bodybody b.b. neurofibrilneurofibril NisslNissl’’ss bodiesbodies LM:LM: basophilicbasophilic massmass oror granulesgranules Nissl’s Body (TEM) EMEM:: RERRER,, freefree RbRb FunctionFunction:: producingproducing thethe proteinprotein ofof neuronneuron structurestructure andand enzymeenzyme producingproducing thethe neurotransmitterneurotransmitter NeurofibrilNeurofibril thethe structurestructure LM:LM: EM:EM: NeurofilamentNeurofilament micmicrotubulerotubule FunctionFunction cytoskeleton,cytoskeleton, toto participateparticipate inin substancesubstance transporttransport LipofuscinLipofuscin (3)(3) CellCell membranemembrane excitableexcitable membranemembrane ,, receivingreceiving stimutation,stimutation, fromingfroming andand conductingconducting nervenerve impulesimpules neurite: 1.2 Dendrite dendritic spine spine apparatus Function: 1.3 Axon axon hillock, axon terminal, axolemma Axoplasm: microfilament, microtubules, neurofilament, mitochondria, -

Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond

cells Review Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond Sarah Kuhn y, Laura Gritti y, Daniel Crooks and Yvonne Dombrowski * Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (L.G.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0044-28-9097-6127 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 7 November 2019; Published: 12 November 2019 Abstract: Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS) that are generated from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC). OPC are distributed throughout the CNS and represent a pool of migratory and proliferative adult progenitor cells that can differentiate into oligodendrocytes. The central function of oligodendrocytes is to generate myelin, which is an extended membrane from the cell that wraps tightly around axons. Due to this energy consuming process and the associated high metabolic turnover oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to cytotoxic and excitotoxic factors. Oligodendrocyte pathology is therefore evident in a range of disorders including multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Deceased oligodendrocytes can be replenished from the adult OPC pool and lost myelin can be regenerated during remyelination, which can prevent axonal degeneration and can restore function. Cell population studies have recently identified novel immunomodulatory functions of oligodendrocytes, the implications of which, e.g., for diseases with primary oligodendrocyte pathology, are not yet clear. Here, we review the journey of oligodendrocytes from the embryonic stage to their role in homeostasis and their fate in disease. We will also discuss the most common models used to study oligodendrocytes and describe newly discovered functions of oligodendrocytes. -

Neuregulin 1–Erbb2 Signaling Is Required for the Establishment of Radial Glia and Their Transformation Into Astrocytes in Cerebral Cortex

Neuregulin 1–erbB2 signaling is required for the establishment of radial glia and their transformation into astrocytes in cerebral cortex Ralf S. Schmid*, Barbara McGrath*, Bridget E. Berechid†, Becky Boyles*, Mark Marchionni‡, Nenad Sˇ estan†, and Eva S. Anton*§ *University of North Carolina Neuroscience Center and Department of Cell and Molecular Physiology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; †Department of Neurobiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510; and ‡CeNes Pharamceuticals, Inc., Norwood, MA 02062 Communicated by Pasko Rakic, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, January 27, 2003 (received for review December 12, 2002) Radial glial cells and astrocytes function to support the construction mine whether NRG-1-mediated signaling is involved in radial and maintenance, respectively, of the cerebral cortex. However, the glial cell development and differentiation in the cerebral cortex. mechanisms that determine how radial glial cells are established, We show that NRG-1 signaling, involving erbB2, may act in maintained, and transformed into astrocytes in the cerebral cortex are concert with Notch signaling to exert a critical influence in the not well understood. Here, we show that neuregulin-1 (NRG-1) exerts establishment, maintenance, and appropriate transformation of a critical role in the establishment of radial glial cells. Radial glial cell radial glial cells in cerebral cortex. generation is significantly impaired in NRG mutants, and this defect can be rescued by exogenous NRG-1. Down-regulation of expression Materials and Methods and activity of erbB2, a member of the NRG-1 receptor complex, leads Clonal Analysis to Study NRG’s Role in the Initial Establishment of to the transformation of radial glial cells into astrocytes. -

Acute Reduction of Microglia Does Not Alter Axonal Injury in a Mouse Model of Repetitive Concussive Traumatic Brain Injury Rachel E

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2014 Acute reduction of microglia does not alter axonal injury in a mouse model of repetitive concussive traumatic brain injury Rachel E. Bennett Washington University School of Medicine David L. Brody Washington University School of Medicine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Bennett, Rachel E. and Brody, David L., ,"Acute reduction of microglia does not alter axonal injury in a mouse model of repetitive concussive traumatic brain injury." Journal of Neurotrauma.31,9. 1647-1663. (2014). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/4711 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOURNAL OF NEUROTRAUMA 31:1647–1663 (October 1, 2014) ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2013.3320 Acute Reduction of Microglia Does Not Alter Axonal Injury in a Mouse Model of Repetitive Concussive Traumatic Brain Injury Rachel E. Bennett and David L. Brody Abstract The pathological processes that lead to long-term consequences of multiple concussions are unclear. Primary mechanical damage to axons during concussion is likely to contribute to dysfunction. Secondary damage has been hypothesized to be induced or exacerbated by inflammation. The main inflammatory cells in the brain are microglia, a type of macrophage. This research sought to determine the contribution of microglia to axon degeneration after repetitive closed-skull traumatic brain injury (rcTBI) using CD11b-TK (thymidine kinase) mice, a valganciclovir-inducible model of macrophage depletion. -

A System for Studying Mechanisms of Neuromuscular Junction Development and Maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2016) 143, 2464-2477 doi:10.1242/dev.130278 TECHNIQUES AND RESOURCES RESEARCH ARTICLE A system for studying mechanisms of neuromuscular junction development and maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R. Gomes1,3,*,‡ ABSTRACT different animal models and cell lines (Chen et al., 2014; Corti et al., The neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a cellular synapse between a 2012; Lenzi et al., 2015) with the hope of recapitulating some motor neuron and a skeletal muscle fiber, enables the translation of features of neuromuscular diseases and understanding the triggers chemical cues into physical activity. The development of this special of one of their common hallmarks: the disruption of the structure has been subject to numerous investigations, but its neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The NMJ is one of the most complexity renders in vivo studies particularly difficult to perform. studied synapses. It is formed of three key elements: the lower motor In vitro modeling of the neuromuscular junction represents a powerful neuron (the pre-synaptic compartment), the skeletal muscle (the tool to delineate fully the fine tuning of events that lead to subcellular post-synaptic compartment) and the Schwann cell (Sanes and specialization at the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic sites. Here, we Lichtman, 1999). The NMJ is formed in a step-wise manner describe a novel heterologous co-culture in vitro method using rat following a series of cues involving these three cellular components spinal cord explants with dorsal root ganglia and murine primary and its role is basically to ensure the skeletal muscle functionality. -

Was Not Reached, However, Even After Six to Sevenhours. A

PROTEIN SYNTHESIS IN THE ISOLATED GIANT AXON OF THE SQUID* BY A. GIUDITTA,t W.-D. DETTBARN,t AND MIROSLAv BRZIN§ MARINE BIOLOGICAL LABORATORY, WOODS HOLE, MASSACHUSETTS Communicated by David Nachmansohn, February 2, 1968 The work of Weiss and his associates,1-3 and more recently of a number of other investigators,4- has established the occurrence of a flux of materials from the soma of neurons toward the peripheral regions of the axon. It has been postulated that this mechanism would account for the origin of most of the axonal protein, although the time required to cover the distance which separates some axonal tips from their cell bodies would impose severe delays.4 On the other hand, a number of observations7-9 have indicated the occurrence of local mechanisms of synthesis in peripheral axons, as suggested by the kinetics of appearance of individual proteins after axonal transection. In this paper we report the incorporation of radioactive amino acids into the protein fraction of the axoplasm and of the axonal envelope obtained from giant axons of the squid. These axons are isolated essentially free from small fibers and connective tissue, and pure samples of axoplasm may be obtained by extru- sion of the axon. Incorporation of amino acids into axonal protein has recently been reported using systems from mammals'0 and fish."I Materials and Methods.-Giant axons of Loligo pealii were dissected and freed from small fibers: they were tied at both ends. Incubations were carried out at 18-20° in sea water previously filtered through Millipore which contained 5 mM Tris pH 7.8 and 10 Muc/ml of a mixture of 15 C'4-labeled amino acids (New England Nuclear Co., Boston, Mass.). -

(Caspr) and Contactin Form a Complex That Is Targeted to the Paranodal Junctions During Myelination

The Journal of Neuroscience, November 15, 2000, 20(22):8354–8364 Contactin-Associated Protein (Caspr) and Contactin Form a Complex That Is Targeted to the Paranodal Junctions during Myelination Jose C. Rios,1 Carmen V. Melendez-Vasquez,1 Steven Einheber,1 Marc Lustig,2 Martin Grumet,2 John Hemperly,5 Elior Peles,6 and James L. Salzer1,3,4 Departments of 1Cell Biology, 2Pharmacology, 3Neurology, and the 4Kaplan Cancer Center, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York 10016, 5BD Technologies, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709, and 6Department of Molecular Cell Biology, The Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel Specialized paranodal junctions form between the axon and the associated specifically with Caspr in the paranodes, whereas a closely apposed paranodal loops of myelinating glia. They are higher-molecular-weight form of contactin, not associated with interposed between sodium channels at the nodes of Ranvier Caspr, is present in central nodes of Ranvier. These results and potassium channels in the juxtaparanodal regions; their suggest that the targeting of contactin to different axonal do- precise function and molecular composition have been elusive. mains may be determined, in part, via its association with Caspr. We previously reported that Caspr (contactin-associated protein) Treatment of myelinating cocultures of Schwann cells and neu- is a major axonal constituent of these junctions (Einheber et al., rons with RPTP–Fc, a soluble construct containing the carbonic 1997). We now report that contactin colocalizes and forms a cis anhydrase domain of the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase complex with Caspr in the paranodes and juxtamesaxon. -

View Software

TLR4-activated microglia have divergent effects on oligodendrocyte lineage cells DISSERTATION Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Evan Zachary Goldstein, BA Neuroscience Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Dana McTigue, Advisor Dr. Phillip Popovich Dr. Jonathan Godbout Dr. Courtney DeVries Copyright by Evan Zachary Goldstein 2016 i Abstract Myelin accelerates action potential conduction velocity and provides essential metabolic support for axons. Unfortunately, myelin and myelinating cells are often vulnerable to injury or disease, resulting in myelin damage, which in turn can lead to axon dysfunction, overt pathology and neurological impairment. Inflammation is a common component of CNS trauma and disease, and therefore an active inflammatory response is often considered deleterious to myelin health. While inflammation can certainly damage myelin, inflammatory processes also benefit oligodendrocyte (OL) lineage progression and myelin repair. Consistent with the divergent nature of inflammation, intraspinal toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation, an innate immune pathway, kills OL lineage cells, but also initiates oligodendrogenesis. Soluble factors produced by TLR4-activated microglia can reproduce these effects in vitro, however the exact factors are unknown. To determine what microglial factors might contribute to TLR4-induced OL loss and oligodendrogenesis, mRNA of factors known to affect OL lineage cells was quantified in TLR4-activated microglia and spinal cords (chapter 2). Results indicate that TLR4-activated microglia transcribe numerous factors that induce OL loss, OL progenitor cell (OPC) proliferation and OPC differentiation. However, some factors upregulated after intraspinal TLR4 activation were not ii upregulated by microglia, suggesting that other cell types contribute to transcriptional changes in vivo. -

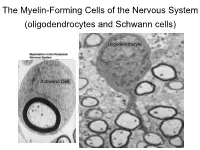

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Specific Labeling of Synaptic Schwann Cells Reveals Unique Cellular And

RESEARCH ARTICLE Specific labeling of synaptic schwann cells reveals unique cellular and molecular features Ryan Castro1,2,3, Thomas Taetzsch1,2, Sydney K Vaughan1,2, Kerilyn Godbe4, John Chappell4, Robert E Settlage5, Gregorio Valdez1,2,6* 1Department of Molecular Biology, Cellular Biology, and Biochemistry, Brown University, Providence, United States; 2Center for Translational Neuroscience, Robert J. and Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science and Brown Institute for Translational Science, Brown University, Providence, United States; 3Neuroscience Graduate Program, Brown University, Providence, United States; 4Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at Virginia Tech Carilion, Roanoke, United States; 5Department of Advanced Research Computing, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, United States; 6Department of Neurology, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, United States Abstract Perisynaptic Schwann cells (PSCs) are specialized, non-myelinating, synaptic glia of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), that participate in synapse development, function, maintenance, and repair. The study of PSCs has relied on an anatomy-based approach, as the identities of cell-specific PSC molecular markers have remained elusive. This limited approach has precluded our ability to isolate and genetically manipulate PSCs in a cell specific manner. We have identified neuron-glia antigen 2 (NG2) as a unique molecular marker of S100b+ PSCs in skeletal muscle. NG2 is expressed in Schwann cells already associated with the NMJ, indicating that it is a marker of differentiated PSCs. Using a newly generated transgenic mouse in which PSCs are specifically labeled, we show that PSCs have a unique molecular signature that includes genes known to play critical roles in *For correspondence: PSCs and synapses. These findings will serve as a springboard for revealing drivers of PSC [email protected] differentiation and function. -

11 Introduction to the Nervous System and Nervous Tissue

11 Introduction to the Nervous System and Nervous Tissue ou can’t turn on the television or radio, much less go online, without seeing some- 11.1 Overview of the Nervous thing to remind you of the nervous system. From advertisements for medications System 381 Yto treat depression and other psychiatric conditions to stories about celebrities and 11.2 Nervous Tissue 384 their battles with illegal drugs, information about the nervous system is everywhere in 11.3 Electrophysiology our popular culture. And there is good reason for this—the nervous system controls our of Neurons 393 perception and experience of the world. In addition, it directs voluntary movement, and 11.4 Neuronal Synapses 406 is the seat of our consciousness, personality, and learning and memory. Along with the 11.5 Neurotransmitters 413 endocrine system, the nervous system regulates many aspects of homeostasis, including 11.6 Functional Groups respiratory rate, blood pressure, body temperature, the sleep/wake cycle, and blood pH. of Neurons 417 In this chapter we introduce the multitasking nervous system and its basic functions and divisions. We then examine the structure and physiology of the main tissue of the nervous system: nervous tissue. As you read, notice that many of the same principles you discovered in the muscle tissue chapter (see Chapter 10) apply here as well. MODULE 11.1 Overview of the Nervous System Learning Outcomes 1. Describe the major functions of the nervous system. 2. Describe the structures and basic functions of each organ of the central and peripheral nervous systems. 3. Explain the major differences between the two functional divisions of the peripheral nervous system. -

Chapter 22 – Neuromuscular Physiology and Pharmacology J. A. Jeevendra Martyn

Chapter 22 – Neuromuscular Physiology and Pharmacology J. A. Jeevendra Martyn The physiology of neuromuscular transmission could be analyzed and understood at the most simple level by using the classic model of nerve signaling to muscle through the acetylcholine receptor. The mammalian neuromuscular junction is the prototypical and most extensively studied synapse. Research has provided more detailed information on the processes that, within the classic scheme, can modify neurotransmission and response to drugs. One example of this is the role of qualitative or quantitative changes in acetylcholine receptors modifying neurotransmission and response to drugs.[1][2] In myasthenia gravis, for example, the decrease in acetylcholine receptors results in decreased efficiency of neurotransmission (and therefore muscle weakness)[3] and altered sensitivity to neuromuscular relaxants.[1][2] Another example is the importance of nerve-related (prejunctional) changes that alter neurotransmission and response to drugs.[1][4] At still another level is the evidence that muscle relaxants act in ways that are not encompassed by the classic scheme of unitary site of action. The observation that muscle relaxants can have prejunctional effects[5] or that some nondepolarizers can also have agonist-like stimulatory actions on the receptor[6] while others have effects not explainable by purely postsynaptic events[7] has provided new insights into some previously unexplained observations. Although this multifaceted action-response scheme makes the physiology and