Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

SCQF Level 6 Bagpipes Practical

Z The Royal Scottish Pipe Band Association Pipe Band College Certification Education Guidelines PDQB CERTIFICATE - SCQF 6 Bagpipes This guide is intended for both Students and Instructors. It must be read in conjunction with SCQF 6 Bagpipes Syllabus to ensure all aspects are covered. Refer www.pdqb.org. It is strongly recommended that all students sitting this level have access to the RSPBA Structured Learning Books. It is also recommended to purchase The College of Piping Tutor 4 – Piobaireachd be purchased. It is therefore important that Instructors use these recommended books as their main source material. The RSPBA Structured Learning Books are available free from the RSPBA Pipe Band College :- https://www.rspba.org/ Obtain College of Piping Tutor 4 Knowledge of SCQF 2 through 5 are essential for SCQF 6. Students who start at SCQF 6 may be required to prove competency of prior levels by the Examiner. Be prepared for this. Theory Aspects: • Write bars of a monotone rhythm in various combinations e.g. Compound Duple time / Cut Common time / Common time etc. And be able to consider rests in the combinations and ensure each bar has different combination of note values. • Explain the accent pattern in reels and describe two important factors in reel playing – could be any type of tune – say Reel or Strathspey etc– accent pattern - Simple Duple Time meaning 2 beats in the Bar SW for reel or Simple Quadruple Time SWMW for Strathspey etc. – important factors in playing different types of tunes – discuss this e.g. good technique, appropriate tempo, decision of round or dot cut etc. -

1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate's Close Proximity to The

Edinburgh Graveyards Project: Documentary Survey For Canongate Kirkyard --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate’s close proximity to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which is situated at the eastern end of Canongate Burgh, has been influential on both the fortunes of the Burgh and the establishment of Canongate Kirk. In 1687, King James VII declared that the Abbey Church of Holyroodhouse was to be used as the chapel for the re-established Order of the Thistle and for the performance of Catholic rites when the Royal Court was in residence at Holyrood. The nave of this chapel had been used by the Burgh of Canongate as a place of Protestant worship since the Reformation in the mid sixteenth century, but with the removal of access to the Abbey Church to practise their faith, the parishioners of Canongate were forced to find an alternative venue in which to worship. Fortunately, some 40 years before this edict by James VII, funds had been bequeathed to the inhabitants of Canongate to erect a church in the Burgh - and these funds had never been spent. This money was therefore used to build Canongate Kirk and a Kirkyard was laid out within its grounds shortly after building work commenced in 1688. 1 Development It has been ruminated whether interments may have occurred on this site before the construction of the Kirk or the landscaping of the Kirkyard2 as all burial rights within the church had been removed from the parishioners of the Canongate in the 1670s, when the Abbey Church had became the chapel of the King.3 The earliest known plan of the Kirkyard dates to 1765 (Figure 1), and depicts a rectilinear area on the northern side of Canongate burgh with arboreal planting 1 John Gifford et al., Edinburgh, The Buildings of Scotland: Pevsner Architectural Guides (London : Penguin, 1991). -

NOTING the TRADITION an Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre

NOTING THE TRADITION An Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre Interviewee Professor Roddy Cannon Interviewer James Beaton Date of Interview 30 th November 2012 This interview is copyright of the National Piping Centre Please refer to the Noting the Tradition Project Manager at the National Piping Centre, prior to any broadcast of or publication from this document. Project Manager Noting The Tradition The National Piping Centre 30-34 McPhater Street Glasgow G4 0HW [email protected] Copyright, The National Piping Centre 2012 This is James Beaton for ‘Noting the Tradition.’ I’m here in the National Piping Centre with Professor Roddy Cannon, piper, piping historian and researcher, and also professionally a scientist. It’s St Andrew’s Day 2012 and we’re going to be speaking really about Roddy’s life and times in piping. Roddy, good morning and welcome. Good morning. Good morning. It’s always good to be back. Well, it’s nice to see you here and it’s nice to have you back. I come here on averageabout once a year these days. I give a number of classes and I talk to your students and I talk to the staff and I talk to you and it’s wonderful. Well, it’s nice to have you here. The thing that strikes me very much about your classes is that they’re so different from one year to the next. Some sit quietly and listen, some of them join the debate vigorously, and very occasionally I get confuted by counter arguments and that’s what I like best. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

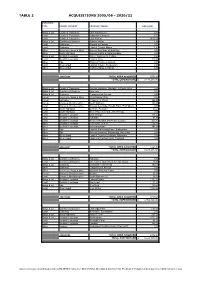

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

Robert Burns, His Medical Friends, Attendants and Biographer*

ROBERT BURNS, HIS MEDICAL FRIENDS, ATTENDANTS AND BIOGRAPHER* By H. B. ANDERSON, M.D. TORONTO NE hundred and twenty-seven untimely death was a mystery for which fl years have elapsed since Dr. James some explanation had to be proffered. I Currie, f .r .s ., of Liverpool, pub- Two incidents, however, discredit Syme Iished the first and greatest biog- as a dependable witness: the sword incident, raphy of Robert Burns. on the occasion of his reproving the poet Dr. Currie had met the poet but once and regarding his habits, of which there are then only for a few minutes in the streets several conflicting accounts, and his apoc- of Dumfries, so that he was entirely depend- ryphal version of the circumstances under ent on others for the information on which which “Scots Wha Hae” was produced he based his opinions of the character and during the Galloway tour. In regard to the habits of Burns. A few days after Burns’ latter incident, the letter Burns wrote death he wrote to John Syme, “Stamp-office Thomson in forwarding the poem effectually Johnnie,” an old college friend then living disposes of Syme’s fabrication. in Dumfries: “ By what I have heard, he was As Burns’ biographer, Dr. Currie is known not very correct in his conduct, and a report to have been actuated by admiration, goes about that he died of the effects of friendship, and the benevolent purpose of habitual drinking.” But doubting the truth- helping to provide for the widow and family; fulness of the current gossip, he asks Syme and it is quite evident that he was willing, pointedly “What did Burns die of?” It is if not anxious, to undertake the task. -

Battle of Culloden

Battle of Culloden The Battle of Culloden (Scottish Gaelic: Blàr Chùil Lodair) was the final confrontation of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. On 16 April 1746, the Jacobite forces of Charles Edward Stuart fought loyalist troops commanded by William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands. The Hanoverian victory at Culloden decisively halted the Jacobite intent to overthrow the House of Hanover and restore the House of Stuart to the British throne; Charles Stuart never mounted any further attempts to challenge Hanoverian power in Great Britain. Between 1,500 and 2,000 Jacobites were killed or wounded in the brief battle. The aftermath of the battle and subsequent crackdown on Jacobitism was brutal, earning Cumberland the sobriquet "Butcher". Efforts were subsequently taken to further integrate the comparatively wild Highlands into the Kingdom of Great Britain; civil penalties were introduced to weaken Gaelic culture and destroy the Scottish clan system. On the 16th April, 1746, one of the two Macdonald’s of Sleat, Capt. Donald Roy Macdonald, took part in the battle of Culloden. In the retreat he twice saw Alexander of Keppoch fall to the ground wounded. After the second fall Keppoch looked up at Donald Roy and said: "O God, have mercy upon me. Donald do the best for yourself, for I am gone." Donald Roy then left him and in leaving the field he received a musket wound which went in at the sole of the left foot and out at the buckle. During the eight week period he was hiding in three caves, wounded, alone and in pain, in wrote the following Latin Laments - now translated into English, revealing his thoughts and feelings - a vivid reflection of this highlander in context of post Culloden 1746. -

Historical Records of the 79Th Cameron Highlanders

%. Z-. W ^ 1 "V X*"* t-' HISTORICAL RECORDS OF THE 79-m QUEEN'S OWN CAMERON HIGHLANDERS antr (Kiritsft 1m CAPTAIN T. A. MACKENZIE, LIEUTENANT AND ADJUTANT J. S. EWART, AND LIEUTENANT C. FINDLAY, FROM THE ORDERLY ROOM RECORDS. HAMILTON, ADAMS & Co., 32 PATERNOSTER Row. JDebonport \ A. H. 111 112 FOUE ,STRSET. SWISS, & ; 1887. Ms PRINTED AT THE " " BREMNER PRINTING WORKS, DEVOXPORT. HENRY MORSE STETHEMS ILLUSTRATIONS. THE PHOTOGRAVURES are by the London Typographic Etching Company, from Photographs and Engravings kindly lent by the Officers' and Sergeants' Messes and various Officers of the Regiment. The Photogravure of the Uniform Levee Dress, 1835, is from a Photograph of Lieutenant Lumsden, dressed in the uniform belonging to the late Major W. A. Riach. CONTENTS. PAGK PREFACE vii 1793 RAISING THE REGIMENT 1 1801 EGYPTIAN CAMPAIGN 16 1808 PENINSULAR CAMPAIGN .. 27 1815 WATERLOO CAMPAIGN .. 54 1840 GIBRALTAR 96 1848 CANADA 98 1854 CRIMEAN CAMPAIGN 103 1857 INDIAN MUTINY 128 1872 HOME 150 1879 GIBRALTAR ... ... .. ... 161 1882 EGYPTIAN CAMPAIGN 166 1884 NILE EXPEDITION ... .'. ... 181 1885 SOUDAN CAMPAIGN 183 SERVICES OF THE OFFICERS 203 SERVICES OF THE WARRANT OFFICERS ETC. .... 291 APPENDIX 307 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS, SIR JOHN DOUGLAS Frontispiece REGIMENTAL COLOUR To face SIR NEIL DOUGLAS To face 56 LA BELLE ALLIANCE : WHERE THE REGIMENT BIVOUACKED AFTER THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO .. ,, 58 SIR RONALD FERGUSON ,, 86 ILLUSTRATION OF LEVEE DRESS ,, 94 SIR RICHARD TAYLOR ,, 130 COLOURS PRESENTED BY THE QUEEN ,, 152 GENERAL MILLER ,, 154 COLONEL CUMING ,, 160 COLONEL LEITH , 172 KOSHEH FORT ,, 186 REPRESENTATIVE GROUP OF CAMERON HIGHLANDERS 196 PREFACE. WANT has long been felt in the Regiment for some complete history of the 79th Cameron Highlanders down to the present time, and, at the request of Lieutenant-Colonel Everett, D-S.O., and the officers of the Regiment a committee, con- Lieutenant and sisting of Captain T. -

Argyll Bird Report with Sstematic List for the Year

ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Volume 15 (1999) PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB Cover picture: Barnacle Geese by Margaret Staley The Fifteenth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by P.C. Daw Systematic List by P.C. Daw Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Scottish Charity Number SC008782) October 1999 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Printed by Printworks Oban - ABOUT THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 19x5. Its main purpose is to play an active part in the promotion of ornithology in Argyll. It is recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity in Scotland. The Club holds two one-day meetings each year, in spring and autumn. The venue of the spring meeting is rotated between different towns, including Dunoon, Oban. LochgilpheadandTarbert.Thc autumn meeting and AGM are usually held in Invenny or another conveniently central location. The Club organises field trips for members. It also publishes the annual Argyll Bird Report and a quarterly members’ newsletter, The Eider, which includes details of club activities, reports from meetings and field trips, and feature articles by members and others, Each year the subscription entitles you to the ArgyZl Bird Report, four issues of The Eider, and free admission to the two annual meetings. There are four kinds of membership: current rates (at 1 October 1999) are: Ordinary E10; Junior (under 17) E3; Family €15; Corporate E25 Subscriptions (by cheque or standing order) are due on 1 January. Anyonejoining after 1 Octoberis covered until the end of the following year. -

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents 4 President’s Message Music 5 Editorial 33 Jimmy Tweedie’s Sealegs 6 Letters to the Editor 43 Report for the Reviews Executive Secretary 34 Review of Gibson Pipe Chanter Spring 2015 35 The Campbell Vol. 44, No. 1 Basics Tunable Chanter 9 Snare Basics: Snare FAQ THE VOICE is the official publication of the Eastern United 11 Bass & Tenor Basics: Semiquavers States Pipe Band Association. Writing a Basic Tenor Score 35 The Making of the 13 Piping Basics: “Piob-ogetics” Casco Bay Contest John Bottomley 37 Pittsburgh Piping EDITOR [email protected] Features Society Reborn 15 Interview Shawn Hall 17 Bands, Games Come Together Branch Notes ART DIRECTOR 19 Willie Wows ‘Em 39 Southwest Branch [email protected] 21 The Last Happy Days – 39 Metro Branch Editorial Inquiries/Letters the Great Highland Bagpipe 40 Ohio Valley Branch THE VOICE in JFK’s Camelot 41 Northeast Branch [email protected] ADVERTISING INQUIRIES John Bottomley [email protected] THE VOICE welcomes submissions, news items, and ON THE COVER: photographs. Please send your Derek Midgley captured the joy submissions to the email above. of early St. Patrick’s parades in the northeast with this photo of Rich Visit the EUSPBA online at www.euspba.org Harvey’s pipe at the Belmar NJ event. ©2014 Eastern United States Pipe Band EUSPBA MEMBERS receive a subscription to THE VOICE paid for, in part, Association. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced or transmitted by their dues ($8 per member is designated for THE VOICE).