Aesthetics at Its Very Limits: Art History Meets Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2017 Vol

International Bear News Tri-Annual Newsletter of the International Association for Bear Research and Management (IBA) and the IUCN/SSC Bear Specialist Group Fall 2017 Vol. 26 no. 3 Sun bear. (Photo: Free the Bears) Read about the first Sun Bear Symposium that took place in Malaysia on pages 34-35. IBA website: www.bearbiology.org Table of Contents INTERNATIONAL BEAR NEWS 3 International Bear News, ISSN #1064-1564 MANAGER’S CORNER IBA PRESIDENT/IUCN BSG CO-CHAIRS 4 President’s Column 29 A Discussion of Black Bear Management 5 The World’s Least Known Bear Species Gets 30 People are Building a Better Bear Trap its Day in the Sun 33 Florida Provides over $1 million in Incentive 7 Do You Have a Paper on Sun Bears in Your Grants to Reduce Human-Bear Conflicts Head? WORKSHOP REPORTS IBA GRANTS PROGRAM NEWS 34 Shining a Light on Sun Bears 8 Learning About Bears - An Experience and Exchange Opportunity in Sweden WORKSHOP ANNOUNCEMENTS 10 Spectacled Bears of the Dry Tropical Forest 36 5th International Human-Bear Conflict in North-Western Peru Workshop 12 IBA Experience and Exchange Grant Report: 36 13th Western Black Bear Workshop Sun Bear Research in Malaysia CONFERENCE ANNOUNCEMENTS CONSERVATION 37 26th International Conference on Bear 14 Revival of Handicraft Aides Survey for Research & Management Asiatic Black Bear Corridors in Hormozgan Province, Iran STUDENT FORUM 16 The Andean Bear in Manu Biosphere 38 Truman Listserv and Facebook Page Reserve, Rival or Ally for Communities? 39 Post-Conference Homework for Students HUMAN BEAR CONFLICTS PUBLICATIONS -

Symbolic Use of Marine Shells and Mineral Pigments by Iberian Neandertals

Symbolic use of marine shells and mineral pigments by Iberian Neandertals João Zilhãoa,1, Diego E. Angeluccib, Ernestina Badal-Garcíac, Francesco d’Erricod,e, Floréal Danielf, Laure Dayetf, Katerina Doukag, Thomas F. G. Highamg, María José Martínez-Sánchezh, Ricardo Montes-Bernárdezi, Sonia Murcia-Mascarósj, Carmen Pérez-Sirventh, Clodoaldo Roldán-Garcíaj, Marian Vanhaerenk, Valentín Villaverdec, Rachel Woodg, and Josefina Zapatal aUniversity of Bristol, Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Bristol BS8 1UU, United Kingdom; bUniversità degli Studi di Trento, Laboratorio di Preistoria B. Bagolini, Dipartimento di Filosofia, Storia e Beni Culturali, 38122 Trento, Italy; cUniversidad de Valencia, Departamento de Prehistoria y Arqueología, 46010 Valencia, Spain; dCentre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Mixte de Recherche 5199, De la Préhistoire à l’Actuel: Culture, Environnement et Anthropologie, 33405 Talence, France; eUniversity of the Witwatersrand, Institute for Human Evolution, Johannesburg, 2050 Wits, South Africa; fUniversité de Bordeaux 3, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Mixte de Recherche 5060, Institut de Recherche sur les Archéomatériaux, Centre de recherche en physique appliquée à l’archéologie, 33607 Pessac, France; gUniversity of Oxford, Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, Dyson Perrins Building, Oxford OX1 3QY, United Kingdom; hUniversidad de Murcia, Departamento de Química Agrícola, Geología y Edafología, Facultad de Química, Campus de Espinardo, 30100 Murcia, Spain; iFundación de Estudios Murcianos Marqués de Corvera, 30566 Las Torres de Cotillas (Murcia), Spain; jUniversidad de Valencia, Instituto de Ciencia de los Materiales, 46071 Valencia, Spain; kCentre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Mixte de Recherche 7041, Archéologies et Sciences de l’Antiquité, 92023 Nanterre, France; and lUniversidad de Murcia, Área de Antropología Física, Facultad de Biología, Campus de Espinardo, 30100 Murcia, Spain Communicated by Erik Trinkaus, Washington University, St. -

December 2010

International I F L A Preservation PP AA CC o A Newsletter of the IFLA Core Activity N . 52 News on Preservation and Conservation December 2010 Tourism and Preservation: Some Challenges INTERNATIONAL PRESERVATION Tourism and Preservation: No 52 NEWS December 2010 Some Challenges ISSN 0890 - 4960 International Preservation News is a publication of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Core 6 Activity on Preservation and Conservation (PAC) The Economy of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Conservation that reports on the preservation Valéry Patin activities and events that support efforts to preserve materials in the world’s libraries and archives. 12 IFLA-PAC Bibliothèque nationale de France Risks Generated by Tourism in an Environment Quai François-Mauriac with Cultural Heritage Assets 75706 Paris cedex 13 France Miloš Drdácký and Tomáš Drdácký Director: Christiane Baryla 18 Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 70 Fax: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 80 Cultural Heritage and Tourism: E-mail: [email protected] A Complex Management Combination Editor / Translator Flore Izart The Example of Mauritania Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 71 Jean-Marie Arnoult E-mail: fl [email protected] Spanish Translator: Solange Hernandez Layout and printing: STIPA, Montreuil 24 PAC Newsletter is published free of charge three times a year. Orders, address changes and all The Challenge of Exhibiting Dead Sea Scrolls: other inquiries should be sent to the Regional Story of the BnF Exhibition on Qumrân Manuscripts Centre that covers your area. 3 See -

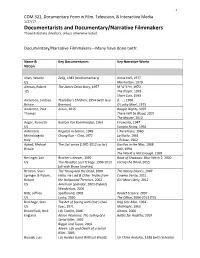

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Bataille Looking 125

NOLAND / bataille looking 125 Bataille Looking Carrie Noland “Dans ce livre, j’ai voulu montrer . .” MODERNISM / modernity Georges Bataille’s Lascaux, ou la naissance de l’art (Lascaux, VOLUME ELEVEN, NUMBER or the Birth of Art) is a commissioned work.1 And, like all com- ONE, PP 125–160. missioned works, Lascaux bears the scars of compromise. To a © 2004 THE JOHNS reader well-versed in Bataille’s major works of the 1930s, how- HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS ever, the large-format, lushly illustrated volume of 1955 appears almost lacerated, a patchwork of textual summaries (of Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens and Roger Caillois’s L’Homme et le sacré, for instance) roughly stitched together at the seams. Bataille seems to have set himself the ambitious task of fitting all the pieces together, reconciling a generation of speculations on Paleolithic image-making with his own already well-devel- oped theories on the implication of art in religious action. Many of Bataille’s most faithful readers have found his study of “pre- historic art” disappointing, signaling a “retrenchment” rather than an advance.2 In Jay Caplan’s words, Bataille’s arguments in Lascaux are all too “familiar,”3 while for Michel Surya the work as a whole is “of less interest” than the contemporaneous La Carrie J. Noland is 4 souveraineté (1954) or Ma mère (1955). Associate Professor of In contrast, I will argue here that Lascaux is indeed a signifi- French at the University cant book, not only in its own right but also as a precursor to of California, Irvine. -

Free-Living Amoebae in Sediments from the Lascaux Cave in France Angela M

International Journal of Speleology 42 (1) 9-13 Tampa, FL (USA) January 2013 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs/ & www.ijs.speleo.it International Journal of Speleology Official Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Free-living amoebae in sediments from the Lascaux Cave in France Angela M. Garcia-Sanchez 1, Concepcion Ariza 2, Jose M. Ubeda 2, Pedro M. Martin-Sanchez 1, Valme Jurado 1, Fabiola Bastian 3, Claude Alabouvette 3, and Cesareo Saiz-Jimenez 1* 1 Instituto de Recursos Naturales y Agrobiología, IRNAS-CSIC, 41012 Sevilla, Spain 2 Universidad de Sevilla, Departamento de Microbiología y Parasitología, Facultad de Farmacia, 41012 Sevilla, Spain 3 UMR INRA-Université de Bourgogne, Microbiologie du Sol et de l’Environment, 21065 Dijon Cedex, France Abstract: The Lascaux Cave in France is an old karstic channel where the running waters are collected in a pool and pumped to the exterior. It is well-known that water bodies in the vicinity of humans are suspected to be reservoirs of amoebae and associated bacteria. In fact, the free-living amoebae Acanthamoeba astronyxis, Acanthamoeba castellanii, Acanthamoeba sp. and Hartmannella vermiformis were identif ied in the sediments of the cave using phylogenetic analyses and morphological traits. Lascaux Cave sediments and rock walls are wet due to a relative humidity near saturation and water condensation, and this environment and the presence of abundant bacterial communities constitute an ideal habitat for amoebae. The data suggest the need to carry out a detailed survey on all the cave compartments in order to determine the relationship between amoebae and pathogenic bacteria. Keywords: free living amoebae; Acanthamoeba; Hartmannella; Lascaux Cave; sediments Received 5 April 2012; Revised 19 September 2012; Accepted 20 September 2012 Citation: Garcia-Sanchez A.M., Ariza C., Ubeda J.M. -

The Lives of Creatures Obscure, Misunderstood, and Wonderful: a Volume in Honour of Ken Aplin 1958–2019

Papers in Honour of Ken Aplin edited by Julien Louys, Sue O’Connor and Kristofer M. Helgen Helgen, Kristofer M., Julien Louys, and Sue O’Connor. 2020. The lives of creatures obscure, misunderstood, and wonderful: a volume in honour of Ken Aplin 1958–2019 ..........................149 Armstrong, Kyle N., Ken Aplin, and Masaharu Motokawa. 2020. A new species of extinct False Vampire Bat (Megadermatidae: Macroderma) from the Kimberley Region of Western Australia ........................................................................................................... 161 Cramb, Jonathan, Scott A. Hocknull, and Gilbert J. Price. 2020. Fossil Uromys (Rodentia: Murinae) from central Queensland, with a description of a new Middle Pleistocene species ............................................................................................................. 175 Price, Gilbert J., Jonathan Cramb, Julien Louys, Kenny J. Travouillon, Eleanor M. A. Pease, Yue-xing Feng, Jian-xin Zhao, and Douglas Irvin. 2020. Late Quaternary fossil vertebrates of the Broken River karst area, northern Queensland, Australia ........................ 193 Theden-Ringl, Fenja, Geoffrey S. Hope, Kathleen P. Hislop, and Benedict J. Keaney. 2020. Characterizing environmental change and species’ histories from stratified faunal records in southeastern Australia: a regional review and a case study for the early to middle Holocene ........................................................................................... 207 Brockwell, Sally, and Ken Aplin. 2020. Fauna on -

Ecopsychology

E u r o p e a n J o u r n a l o f Ecopsychology Special Issue: Ecopsychology and the psychedelic experience Edited by: David Luke Volume 4 2013 European Journal of Ecopsychology EDITOR Paul Stevens, The Open University, UK ASSOCIATE EDITORS Martin Jordan, University of Brighton, UK Martin Milton, University of Surrey, UK Designed and formatted using open source software. EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Matthew Adams, University of Brighton, UK Meg Barker, The Open University, UK Jonathan Coope, De Montfort University, UK Lorraine Fish, UK Jamie Heckert, Anarchist Studies Network John Hegarty, Keele University, UK Alex Hopkinson, Climate East Midlands, UK David Key, Footprint Consulting, UK Alex Lockwood, University of Sunderland, UK David Luke, University of Greenwich, UK Jeff Shantz, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, Canada FOCUS & SCOPE The EJE aims to promote discussion about the synthesis of psychological and ecological ideas. We will consider theoretical papers, empirical reports, accounts of therapeutic practice, and more personal reflections which offer the reader insight into new and original aspects of the interrelationship between humanity and the rest of the natural world. Topics of interest include: • Effects of the natural environment on our emotions and wellbeing • How psychological disconnection relates to the current ecological crisis • Furthering our understanding of psychological, emotional and spiritual relationships with nature For more information, please see our website at http://ecopsychology-journal.eu/ or contact us via email: -

E-Print © BERG PUBLISHERS

Time and Mind: The Journal of “But the Image Wants Archaeology, Danger”: Georges Consciousness and Culture Bataille, Werner Volume 5—Issue 1 March 2012 Herzog, and Poetical pp. 33–52 Response to Paleoart DOI: 10.2752/175169712X13182754067386 Reprints available directly Barnaby Dicker and Nick Lee from the publishers Photocopying permitted by licence only Barnaby Dicker teaches at UCA Farnham and is Historiographic Officer at the International Project Centre © Berg 2012 for Research into Events and Situations (IPCRES), Swansea Metropolitan University. His research revolves around conceptual and material innovations in and through graphic technologies and arts. [email protected] Nick Lee is studying for a PhD in the Media Arts Department, Royal Holloway, University of London, which examines the epistemological basis for Marcel Duchamp’s abandonment of painting. He also teaches at the department. [email protected] E-PrintAbstract The high-profile theatrical release of Werner Herzog’s feature-lengthPUBLISHERS documentary filmCave of Forgotten Dreams in Spring 2011 invites reflection on the way in which paleoart is and has been engaged with at a cultural level. By Herzog’s own account, the film falls on the side of poetry, rather than science. This article considers what is at stake in a “poetical” engagement with the scientific findings concerning paleoart and argues that such approaches harbor value for humanity’s understanding of its own history. To this end, Herzog’s work is brought into BERGdialogue with Georges Bataille’s writing on paleoart, in particular, Lascaux—a precedent of poetical engagement. Keywords: Georges Bataille, Werner Herzog, Chauvet © cave, Lascaux Cave, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, poetical methodologies, disciplinary limits, lens-based media Time and Mind Volume 5—Issue 1—March 2012, pp. -

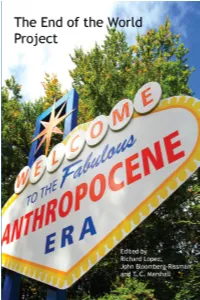

6X9 End of World Msalphabetical

THE END OF THE WORLD PROJECT Edited By RICHARD LOPEZ, JOHN BLOOMBERG-RISSMAN AND T.C. MARSHALL “Good friends we have had, oh good friends we’ve lost, along the way.” For Dale Pendell, Marthe Reed, and Sudan the white rhino TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Trialogue xiii Overture: Anselm Hollo 25 Etel Adnan 27 Charles Alexander 29 Will Alexander 42 Will Alexander and Byron Baker 65 Rae Armantrout 73 John Armstrong 78 DJ Kirsten Angel Dust 82 Runa Bandyopadhyay 86 Alan Baker 94 Carlyle Baker 100 Nora Bateson 106 Tom Beckett 107 Melissa Benham 109 Steve Benson 115 Charles Bernstein 117 Anselm Berrigan 118 John Bloomberg-Rissman 119 Daniel Borzutzky 128 Daniel f Bradley 142 Helen Bridwell 151 Brandon Brown 157 David Buuck 161 Wendy Burk 180 Olivier Cadiot 198 Julie Carr / Lisa Olstein 201 Aileen Cassinetto and C. Sophia Ibardaloza 210 Tom Cohen 214 Claire Colebrook 236 Allison Cobb 248 Jon Cone 258 CA Conrad 264 Stephen Cope 267 Eduardo M. Corvera II (E.M.C. II) 269 Brenda Coultas 270 Anne Laure Coxam 271 Michael Cross 276 Thomas Rain Crowe 286 Brent Cunningham 297 Jane Dalrymple-Hollo 300 Philip Davenport 304 Michelle Detorie 312 John DeWitt 322 Diane Di Prima 326 Suzanne Doppelt 334 Paul Dresman 336 Aja Couchois Duncan 346 Camille Dungy 355 Marcella Durand 359 Martin Edmond 370 Sarah Tuss Efrik and Johannes Göransson 379 Tongo Eisen-Martin 397 Clayton Eshleman 404 Carrie Etter 407 Steven Farmer 409 Alec Finlay 421 Donna Fleischer 429 Evelyn Flores 432 Diane Gage 438 Jeannine Hall Gailey 442 Forrest Gander 448 Renée Gauthier 453 Crane Giamo 454 Giant Ibis 459 Alex Gildzen 460 Samantha Giles 461 C. -

ENRICHMENT ENGAGE, EXPLORE, DISCOVER Years 10-13 Use the Enrichment Links Below Xxcontents | to Engage, Explore and Discover

ENRICHMENT ENGAGE, EXPLORE, DISCOVER Years 10-13 Use the enrichment links below XXContents | to engage, explore and discover. Engage, Explore and Discover I am delighted to be able to introduce this superb enrichment material for us all to use. This wonderful document would not have existed without the extraordinary energy, creativity and intellectual curiosity of my incredible colleagues. There is here a feast for those with a hunger to learn and I would urge all of you to take the opportunity to engage, explore and discover. On a practical note, I would like to draw your attention to some key features of this document. The subjects listed on the contents page have links directly to the relevant pages, with most subjects having sections for both Years 7-9 and 10-13, with the exception of those disciplines that are taught only in the Sixth Form. In addition, there are many links within each subject to online tours, talks, competitions, games and courses as well as books being linked directly to Amazon. I am delighted that the Book Forest has also been included and girls who work their way through the resources on that page alone will discover whole worlds opening up before them. We may restricted in our movements during this time, but our minds are not so confined and the material here will enable each of us to think deeper and wider, examining the world that we live in and our human experience of it from every conceivable angle. Be inquisitive, try new things and who knows what interests and opportunities this confinement may produce. -

Art and Shamanism: from Cave Painting to the White Cube

religions Article Art and Shamanism: From Cave Painting to the White Cube Robert J. Wallis Richmond University, the American International University in London, London TW10 6JP, UK; [email protected] Received: 15 December 2018; Accepted: 8 January 2019; Published: 16 January 2019 Abstract: Art and shamanism are often represented as timeless, universal features of human experience, with an apparently immutable relationship. Shamanism is frequently held to represent the origin of religion and shamans are characterized as the first artists, leaving their infamous mark in the cave art of Upper Palaeolithic Europe. Despite a disconnect of several millennia, modern artists too, from Wassily Kandinsky and Vincent van Gogh, to Joseph Beuys and Marcus Coates, have been labelled as inspired visionaries who access the trance-like states of shamans, and these artists of the ‘white cube’ or gallery setting are cited as the inheritors of an enduring tradition of shamanic art. But critical engagement with the history of thinking on art and shamanism, drawing on discourse analysis, shows these concepts are not unchanging, timeless ‘elective affinities’; they are constructed, historically situated and contentious. In this paper, I examine how art and shamanism have been conceived and their relationship entangled from the Renaissance to the present, focussing on the interpretation of Upper Palaeolithic cave art in the first half of the twentieth century—a key moment in this trajectory—to illustrate my case. Keywords: art; shamanism; elective affinities; entanglement; discourse analysis; cave art; origins of religion; origins of art; Palaeolithic substratum 1. Introduction In this paper, I examine the concepts of art and shamanism, their emergence as terms in European thought, and the way in which they have been perceived to interface in various ways, over time.