Consultations with Indigenous Peoples on Constitutional Recognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic and Social Council

70+6'& ' 0#6+105 'EQPQOKECP5QEKCN Distr. %QWPEKN GENERAL E/CN.4/2004/80/Add.3 17 November 2003 ENGLISH Original: SPANISH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sixtieth session Item 15 of the provisional agenda INDIGENOUS ISSUES Human rights and indigenous issues Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, Mr. Rodolfo Stavenhagen, submitted in accordance with Commission resolution 2003/56 Addendum MISSION TO CHILE* * The executive summary of this report will be distributed in all official languages. The report itself, which is annexed to the summary, will be distributed in the original language and in English. GE.03-17091 (E) 040304 090304 E/CN.4/2004/80/Add.3 page 2 Executive summary This report is submitted in accordance with Commission on Human Rights resolution 2003/56 and covers the official visit to Chile by the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, which took place between 18 and 29 July 2003. In 1993, Chile adopted the Indigenous Peoples Act (Act No. 19,253), in which the State recognizes indigenous people as “the descendants of human groups that have existed in national territory since pre-Colombian times and that have preserved their own forms of ethnic and cultural expression, the land being the principal foundation of their existence and culture”. The main indigenous ethnic groups in Chile are listed as the Mapuche, Aymara, Rapa Nui or Pascuense, Atacameño, Quechua, Colla, Kawashkar or Alacaluf, and Yámana or Yagán. Indigenous peoples in Chile currently represent about 700,000 persons, or 4.6 per cent of the population. -

LARC Resources on Indigenous Languages and Peoples of the Andes Film

LARC Resources on Indigenous Languages and Peoples of the Andes The LARC Lending Library has an extensive collection of educational materials for teacher and classroom use such as videos, slides, units, books, games, curriculum units, and maps. They are available for free short term loan to any instructor in the United States. These materials can be found on the online searchable catalog: http://stonecenter.tulane.edu/pages/detail/48/Lending-Library Film Apaga y Vamonos The Mapuche people of South America survived conquest by the Incas and the Spanish, as well as assimilation by the state of Chile. But will they survive the construction of the Ralco hydroelectric power station? When ENDESA, a multinational company with roots in Spain, began the project in 1997, Mapuche families living along the Biobio River were offered land, animals, tools, and relocation assistance in return for the voluntary exchange of their land. However, many refused to leave; some alleged that they had been marooned in the Andean hinterlands with unsafe housing and, ironically, no electricity. Those who remained claim they have been sold out for progress; that Chile's Indigenous Law has been flouted by then-president Eduardo Frei, that Mapuches protesting the Ralco station have been rounded up and prosecuted for arson and conspiracy under Chile's anti-terrorist legislation, and that many have been forced into hiding to avoid unfair trials with dozens of anonymous informants testifying against them. Newspaper editor Pedro Cayuqueo says he was arrested and interrogated for participating in this documentary. Directed by Manel Mayol. 2006. Spanish w/ English subtitles, 80 min. -

Report on the Work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples Team 2018

Report on the work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples team 2018 1 Report on the work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples team - 2018 Report on the work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples team - 2018 Partnerships and South-South Cooperation Division, Advocacy Unit (DPSA) Background Since the creation of the FAO Indigenous Peoples Team in DPSA in June 2014, the strategy of the team has been to position an agenda of work within FAO, rooted in the 2007 UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and to set in motion the implementation of the 2010 FAO Policy on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. The work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples Team is the result of constant interactions and discussions with indigenous peoples’ representatives. The joint workplan emanating from the 2015 meeting between indigenous representatives and FAO was structured around 6 pillars of work (Advocacy and capacity development; Coordination; Free Prior and Informed Consent; Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests and the Voluntary Guidelines on Small-Scale Fisheries; Indigenous Food Systems; and Food Security Indicators). Resulting from the discussions with indigenous youth in April 2017, a new relevant pillar was outlined related to intergenerational exchange and traditional knowledge in the context of climate change and resilience. In 2017, the work of the FAO Indigenous Peoples Team shifted from advocacy, particularly internal to the Organization, to consolidation and programming. Through a two-year programme of work encompassing the 6+1 pillars of work and the thematic areas – indigenous women and indigenous youth, the Team succeeded in leveraging internal support and resources to implement several of the activities included in the programme of work for 2018. -

In the Shadow of Empire and Nation : Chilean Migration to the United

IN THE SHADOW OF EMPIRE AND NATION: CHILEAN MIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES SINCE 1950 By Cristián Alberto Doña Reveco A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Sociology History 2012 ABSTRACT IN THE SHADOW OF EMPIRE AND NATION: CHILEAN MIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES SINCE 1950 By Cristián Alberto Doña Reveco This dissertation deals with how Chilean emigrants who have migrated to the US since the 1950s remember and define their migration decision in connection to changing historical processes in both the country of origin and that of destination. Using mainly oral histories collected from 30 Chileans I compare the processes that led to their migration; their memories of Chile at the time of migration; the arrival to the United States, as well as their intermediate migrations to other countries; their memories of Chile during the visits to the country of origin; and their self identifications with the countries of origin and destination. I also use census data and migration entry data to characterize and analyze the different waves of Chilean migration to the United States. I separate each wave by a major historical moment. The first wave commences at the end of World War II and the beginnings of the Cold War; the second with the military coup of September 11, 1973; the third with the economic crisis of 1982; and the fourth with the return to democratic governments in 1990. Connecting the oral histories, migration data and historiographies to current approaches to migration decision-making, the study of social memory, and the construction of migrant identities, this dissertation explores the interplay of these multiple factors in the social constructions underlying the decisions to migrate. -

Epidemiology of Dog Bite Incidents in Chile: Factors Related to the Patterns of Human-Dog Relationship

animals Article Epidemiology of Dog Bite Incidents in Chile: Factors Related to the Patterns of Human-Dog Relationship Carmen Luz Barrios 1,2,*, Carlos Bustos-López 3, Carlos Pavletic 4,†, Alonso Parra 4,†, Macarena Vidal 2, Jonathan Bowen 5 and Jaume Fatjó 1 1 Cátedra Fundación Affinity Animales y Salud, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, Parque de Investigación Biomédica de Barcelona, C/Dr. Aiguader 88, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 2 Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Mayor, Camino La Pirámide 5750, Huechuraba, Región Metropolitana 8580745, Chile; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Ciencias Básicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Santo Tomás, Av. Ejército Libertador 146, Santiago, Región Metropolitana 8320000, Chile; [email protected] 4 Departamento de Zoonosis y Vectores, Ministerio de Salud, Enrique Mac Iver 541, Santiago, Región Metropolitana 8320064, Chile; [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (A.P.) 5 Queen Mother Hospital for Small Animals, Royal Veterinary College, Hawkshead Lane, North Mymms, Hertfordshire AL9 7TA, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +56-02-3281000 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Simple Summary: Dog bites are a major public health problem throughout the world. The main consequences for human health include physical and psychological injuries of varying proportions, secondary infections, sequelae, risk of transmission of zoonoses and surgery, among others, which entail costs for the health system and those affected. The objective of this study was to characterize epidemiologically the incidents of bites in Chile and the patterns of human-dog relationship involved. The results showed that the main victims were adults, men. -

Custodians of Culture and Biodiversity

Custodians of culture and biodiversity Indigenous peoples take charge of their challenges and opportunities Anita Kelles-Viitanen for IFAD Funded by the IFAD Innovation Mainstreaming Initiative and the Government of Finland The opinions expressed in this manual are those of the authors and do not nec - essarily represent those of IFAD. The designations employed and the presenta - tion of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, terri - tory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations “developed” and “developing” countries are in - tended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached in the development process by a particular country or area. This manual contains draft material that has not been subject to formal re - view. It is circulated for review and to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The text has not been edited. On the cover, a detail from a Chinese painting from collections of Anita Kelles-Viitanen CUSTODIANS OF CULTURE AND BIODIVERSITY Indigenous peoples take charge of their challenges and opportunities Anita Kelles-Viitanen For IFAD Funded by the IFAD Innovation Mainstreaming Initiative and the Government of Finland Table of Contents Executive summary 1 I Objective of the study 2 II Results with recommendations 2 1. Introduction 2 2. Poverty 3 3. Livelihoods 3 4. Global warming 4 5. Land 5 6. Biodiversity and natural resource management 6 7. Indigenous Culture 7 8. Gender 8 9. -

Guaraníes, Chanés Y Tapietes Del Norte Argentino. Construyendo El “Ñande Reko” Para El Futuro - 1A Ed Ilustrada

guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, mapuche, kolla, wichí, pampa, moqoit/mocoví, omaguaca, ocloya, vilela, mbyá-guaraní, huarpe, mapuche-pehuenche, charrúa, chané, rankül- che, mapuche-tehuelche, atacama, comechingón, lule, sanavirón, chorote, tehuelche, diaguita cacano, selk’nam, diaguita calchaquí, qom/toba, günun-a-küna, chaná, guaycurú, chulupí/nivaclé, tonokoté, guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, mapuche, kolla, wichí, pampa, Guaraníes, chanés y tapietes moqoit/mocoví, omaguaca, ocloya, vilela, mbyá-guaraní, del norte argentino. Construyendo huarpe, mapuche-pehuenche, charrúa, chané, rankül- che, mapuche-tehuelche, atacama, comechingón, lule, el ñande reko para el futuro sanavirón, chorote, tehuelche, diaguita cacano, 2 selk’nam, diaguita calchaquí, qom/toba, günun-a-küna, chaná, guaycurú, chulupí/nivaclé, tonokoté, guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, mapuche, kolla, wichí, pampa, moqoit/mocoví, omaguaca, ocloya, vilela, mbyá-guaraní, huarpe, mapuche-pehuenche, charrúa, chané, rankül- che, mapuche-tehuelche, atacama, comechingón, lule, sanavirón, chorote, tehuelche, diaguita cacano, selk’nam, diaguita calchaquí, qom/toba, günun-a-küna, chaná, guaycurú, chulupí/nivaclé, tonokoté, guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, mapuche, kolla, wichí, pampa, moqoit/mocoví, omaguaca, ocloya, vilela, mbyá-guaraní, huarpe, mapuche-pehuenche, charrúa, chané, rankül- che, mapuche-tehuelche, atacama, comechingón, lule, sanavirón, chorote, tehuelche, diaguita cacano, selk’nam, diaguita calchaquí, qom/toba, günun-a-küna, chaná, guaycurú, chulupí/nivaclé, tonokoté, guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, -

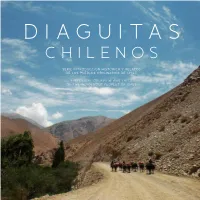

Diaguitas Chilenos

DIAGUITAS CHILENOS SERIE INTRODUCCIÓN HISTÓRICA Y RELATOS DE LOS PUEBLOS ORIGINARIOS DE CHILE HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND TALES OF THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF CHILE DIAGUITAS CHILENOS |3 DIAGUITAS CHILENOS SERIE INTRODUCCIÓN HISTÓRICA Y RELATOS DE LOS PUEBLOS ORIGINARIOS DE CHILE HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND TALES OF THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF CHILE 4| Esta obra es un proyecto de la Fundación de Comunicaciones, Capacitación y Cultura del Agro, Fucoa, y cuenta con el aporte del Fondo Nacional para el Desarrollo de la Cultura y las Artes, Fondart, Línea Bicentenario Redacción, edición de textos y coordinación de contenido: Christine Gleisner, Sara Montt (Unidad de Cultura, Fucoa) Revisión de contenidos: Francisco Contardo Diseño: Caroline Carmona, Victoria Neriz, Silvia Suárez (Unidad de Diseño, Fucoa), Rodrigo Rojas Revisión y selección de relatos en archivos y bibliotecas: María Jesús Martínez-Conde Transcripción de entrevistas: Macarena Solari Traducción al inglés: Focus English Fotografía de Portada: Arrieros camino a la cordillera, Sara Mont Inscripción Registro de Propiedad Intelectual N° 239.029 ISBN: 978-956-7215-52-2 Marzo 2014, Santiago de Chile Imprenta Ograma DIAGUITAS CHILENOS |5 agradeciMientos Quisiéramos expresar nuestra más sincera gratitud al Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes, por haber financiado la investigación y publicación de este libro. Asimismo, damos las gracias a las personas que colaboraron en la realización del presente texto, en especial a: Ernesto Alcayaga, Emeteria Ardiles, Maximino Ardiles, Olinda Campillay, -

Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty Of

Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brad T. Eidahl December 2017 © 2017 Brad T. Eidahl. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile by BRAD T. EIDAHL has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick M. Barr-Melej Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT EIDAHL, BRAD T., Ph.D., December 2017, History Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile Director of Dissertation: Patrick M. Barr-Melej This dissertation examines the struggle between Chile’s opposition press and the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet Ugarte (1973-1990). It argues that due to Chile’s tradition of a pluralistic press and other factors, and in bids to strengthen the regime’s legitimacy, Pinochet and his top officials periodically demonstrated considerable flexibility in terms of the opposition media’s ability to publish and distribute its products. However, the regime, when sensing that its grip on power was slipping, reverted to repressive measures in its dealings with opposition-media outlets. Meanwhile, opposition journalists challenged the very legitimacy Pinochet sought and further widened the scope of acceptable opposition under difficult circumstances. Ultimately, such resistance contributed to Pinochet’s defeat in the 1988 plebiscite, initiating the return of democracy. -

Redalyc.Peculiaridades Morfológicas En El Aymara De La Comuna De Colchane, Chile

Cuadernos Interculturales ISSN: 0718-0586 [email protected] Universidad de Playa Ancha Chile Díaz Vásquez, Enrique; García Choque, Felino Peculiaridades morfológicas en el aymara de la comuna de Colchane, Chile Cuadernos Interculturales, vol. 8, núm. 14, 2010, pp. 165-184 Universidad de Playa Ancha Viña del Mar, Chile Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=55217005010 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Cuadernos Interculturales. Año 8, Nº 14. Primer Semestre 2010, pp. 165-184 165 Peculiaridades morfológicas en el aymara de la comuna de Colchane, Chile*1 Morphological peculiarities in the Aymara of the county of Colchane, Chile Enrique Díaz Vásquez**2 Felino García Choque***3 Resumen Se examinan formas verbales de alta frecuencia en el aymara hablado en la comuna de Colchane, Iquique, en el norte de Chile, a través de un estudio comparativo con las formas verbales equivalentes del aymara de la Paz, Bolivia. Se demuestra que, contraria- mente a las poco significativas diferencias fonológicas detectadas en estudios previos, existen morfológicamente contrastes notables entre las dos variedades, atribuibles a la existencia en el aymara de Colchane de morfemas peculiares para la expresion de la acción continua y la negación en las formas verbales estudiadas. Palabras clave: lengua sintética, morfemas morfológicamente condicionados, elisión vocá- lica, morfemas de aspecto progresivo, morfemas de negación, verbalización de raíces nomi- nales Abstract Some high-frequency verbal forms of the aymara spoken in the county of Colchane, Iquique, in northern Chile, are axamined through a comparative study with the equi- valent verbal forms of the aymara of La Paz, Bolivia. -

Permanent War on Peru's Periphery: Frontier Identity

id2653500 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ’S PERIPHERY: FRONT PERMANENT WAR ON PERU IER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH CENTURY CHILE. By Eugene Clark Berger Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2006 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Date: Jane Landers August, 2006 Marshall Eakin August, 2006 Daniel Usner August, 2006 íos Eddie Wright-R August, 2006 áuregui Carlos J August, 2006 id2725625 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com HISTORY ’ PERMANENT WAR ON PERU S PERIPHERY: FRONTIER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH-CENTURY CHILE EUGENE CLARK BERGER Dissertation under the direction of Professor Jane Landers This dissertation argues that rather than making a concerted effort to stabilize the Spanish-indigenous frontier in the south of the colony, colonists and indigenous residents of 17th century Chile purposefully perpetuated the conflict to benefit personally from the spoils of war and use to their advantage the resources sent by viceregal authorities to fight it. Using original documents I gathered in research trips to Chile and Spain, I am able to reconstruct the debates that went on both sides of the Atlantic over funds, protection from ’ th pirates, and indigenous slavery that so defined Chile s formative 17 century. While my conclusions are unique, frontier residents from Paraguay to northern New Spain were also dealing with volatile indigenous alliances, threats from European enemies, and questions about how their tiny settlements could get and keep the attention of the crown. -

Practices in the Chilean Public

Nº 47, 2015. Páginas 71-81 Diálogo Andino CRITICAL INQUIRY AS A WAY TO BREAK THE GLASS BETWEEN “NORMAL” PRACTICES IN THE CHILEAN PUBLIC ACADEMIA AND THE CASE OF COLOR LATIN AMERICAN MIGRANT STUDENTS IN OUR CLASSROOMS: A CALL TO HUMANIZE, A CALL TO REFLECT UPON LA INVESTIGACIÓN CRÍTICA COMO UNA FORMA DE ROMPER EL CRISTAL ENTRE LAS PRACTICAS ‘COMUNES’ EN LA ACADEMIA PÚBLICA CHILENA Y EL CASO DE LOS ESTUDIANTES MIGRANTES LATINOAMERICANOS DE COLOR EN NUESTRAS SALAS DE CLASES: UN LLAMADO A HUMANIZAR, UN LLAMADO A REFLEXIONAR” Pamela Zapata Sepúlveda*, María Emilia Tijoux Merino** & Michelle Espinoza Lobos*** This essay concerns the critical voices of 3 women researchers that examine and reflect about the Chilean educational system using the case of color Latin American students, in the context and from a current perspective of their public universities in Chile. Public policies in education, integration and segregation, challenges and current problems present or that could ocurr in our classrooms are included in this piece using experimental writing as a critical approach to tell, break silences, and as a way to evoke and pro- voke audiences. Taking a step towards action against social injustice and conservative nationalism and racism in the academia. Key words: Chilean higher education, integraty, social justice, color foreign students, experimental writing, critical methodologies. Este ensayo comprende las voces críticas de tres mujeres investigadoras que analizan y reflexionan sobre el actual sistema educa- cional chileno, usando el caso de los estudiantes de color en la academia. Estas reflexiones giran en torno a las políticas públicas en materia de educación, la integración y la segregación, los retos y los problemas actuales o que puedan ocurrir en nuestras salas de clase, los que son abordados utilizando la escritura experimental como una vía de aproximación crítica para decir, romper silencios, evocar y provocar audiencias.