A Systematic Review of Strategies to Promote Successful Reunification and to Reduce Re-Entry to Care for Abused, Neglected, and Unruly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School of Social Services Administration.Qxp 8/22/2006 8:43 AM Page I

SSA Cover 06-07.qxp 8/22/2006 9:13 AM Page 1 T T HE U NIVERSITY OF HE U NIVERSITY OF C HICAGO C HICAGO T HE S CHOOL OF S OCIAL S ERVICE A DMINISTRATION 2006 – 2007 T HE S CHOOL of S OCIAL S ERVICE A DMINISTRATION A NNOUNCEMENTS 2006-2007 School of Social Services Administration.qxp 8/22/2006 8:43 AM Page i THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE SCHOOL of SOCIAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION ANNOUNCEMENTS Fall 2006 School of Social Services Administration.qxp 8/22/2006 8:43 AM Page ii For information and application materials: Office of Admissions The School of Social Service Administration 969 E. 60th St. Chicago, IL 60637-2940 Telephone: 773-702-1492 [email protected] For information regarding field instruction: Office of Field Instruction Telephone: 773-702-9418 E-mail: [email protected] For university residences information: Neighborhood Student Apartments The University of Chicago 5316 S. Dorchester Ave. Chicago, IL 60615 Telephone: 773-753-2218 International House 1414 E. 58th St. Chicago, IL 60637 Telephone: 773-753-2270 Callers who cannot get through on these numbers may leave a message with the School’s switchboard at 773-702-1250. www.ssa.uchicago.edu 2006-2007 VOLUME XXVI The statements in these Annoucements are subject to change without notice. School of Social Services Administration.qxp 8/22/2006 8:43 AM Page iii TABLE of CONTENTS 1OFFICERS AND ADMINISTRATION 1 Officers of the University 1 Administration of the School 1 Officers of Instruction 2 Faculty Emeriti 3 Visiting Committee 5THE FIELD AND THE SCHOOL 5 The Field of Social Welfare 5 The School of Social Service Administration 6 The Mission of the School 7 The Educational Program 8 Professional Careers 8 The Broader Context 8 The University 9 The City 11 EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS 11 The Master of Arts Program 11 Student Educational Outcomes 12 The Core Curriculum 14 Field Placement 15 The Concentration Curriculum 24 Special Programs 28 Joint Degree Programs 30 Extended Evening Program 30 Doctoral Degree Program 31 Curriculum 31 Supports for Students 32 Requirements for the Ph.D. -

Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President, Kimpton Administration Records 1892-1960

University of Chicago Library Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President, Kimpton Administration Records 1892-1960 © 2007 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Historical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 6 INVENTORY 6 Series I: General Files 6 Series II: Appointments and Budgets 166 Series III: Invitations 174 Series IV: Audiovisual Materials 174 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.OFCPRESKIMPTON Title University of Chicago. Office of the President. Kimpton Administration. Records Date 1892-1960 Size 155.5 linear feet (311 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract This collection contains records of the University of Chicago Office of the President, covering the administration of Lawrence A. Kimpton, who served as Chancellor of the University of Chicago from 1951-1960. While he kept the title of "Chancellor" held by his predecessor, Robert Maynard Hutchins, Kimpton’s duties were consistent with those held throughout the institution’s history by the University President. Included here are administrative records such as correspondence, reports, publications, budgets and personnel material. Information on Use Access Open for research. No restrictions. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: University of Chicago. Office of the President. Records, [Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library Historical Note Lawrence A. Kimpton (1910-1977) was raised in Kansas City, Missouri, attended college at Stanford, and completed a Ph.D. in philosophy at Cornell University in 1935. -

Social Services 04.Qxd

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE SCHOOL of SOCIAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION ANNOUNCEMENTS Fall 2004 For information and application materials: Office of Admissions The School of Social Service Administration 969 E. 60th Street Chicago, IL 60637-2940 Telephone: 773-702-1492 [email protected] For information regarding Field Instruction: Office of Field Instruction Telephone: 773-702-9418 E-mail: [email protected] For University Residences information: Neighborhood Student Apartments The University of Chicago 5316 S. Dorchester Ave. Chicago, IL 60615 Telephone: 773-753-2218 International House 1414 E. 59th Street Chicago, IL 60637 Telephone: 773-753-2270 Callers who cannot get through on these numbers may leave a message with the School’s switchboard at 773-702-1250 www.ssa.uchicago.edu 2004-2005 VOLUME XXIV The statements in these Announcements are subject to change without notice. TABLE of CONTENTS 1OFFICERS 1Officers of the University 1 Administration of the School 1Officers of Instruction 2 Faculty Emeriti 3Visiting Committee 5THE FIELD AND THE SCHOOL 5 The Field of Social Welfare 5 The School of Social Service Administration 6 The Mission of the School 7The Educational Program 8Professional Careers 9 The Broader Context 9 The University 9The City 11 EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS 11 The Master of Arts Program 11 Student Educational Outcomes 12 The Core Curriculum 14 Field Placement 15 The Concentration Curriculum 23 Special Programs 26 Joint Degree Programs 28 Extended Evening Program 28 Doctoral Degree Program 29 Curriculum 29 Supports for -

ISSP Bibliography 2020 ARGENTINA Acosta, Lr and Jorrat, Jr. 2005.”A Simple Alternative to Interpret the Gini Coefficient

ISSP Bibliography 2020 ARGENTINA Acosta, Lr and Jorrat, Jr. 2005.”A simple alternative to interpret the Gini coefficient. An example based on data on education, occupational prestige, and personal net income from urban Argentina." Paper presented at the International Conference in Memory of two eminent social scientists: G. Gini and M.O. Lorenz, Siena, Italy. Anchorena, José, Ronconi, Lucas and Ozawa, Sachiko. 2014.”Social Capital and Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries." Pp. 153-75 in Social Capital and Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Scientific Publishing Co. Anchorena, Jose and Anjos, Fernando. 2015.”Social Ties and Economic Development." Journal of Macroeconomics 45:63-84. Barreiro, Alicia, Arsenio, William F. and Wainryb, Cecilia 2019.”Adolescents’ conceptions of wealth and societal fairness amid extreme inequality: An Argentine sample." Developmental Psychology 55(3):498-508. DOI: 10.1037/dev0000560. Dalle, Pablo. 2010.”Cambios en el regimen de movilidad social intergeneracional en el Area Metropolitana de Buenos Aires (1960-2005) [Changes in intergenerational social mobility regime in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (1960-2005)." Revista latinoamericana de poblacion 4(7). Dalle, Pablo. 2015.”Movilidad social intergeneracional en Argentina. Oportunidades sin apertura de la estructura de clases." Revista de Ciencias Sociales 28(37):139-65. Dalle, Pablo, Carrascosa, Joaquin, Lazarte, Lautaro, Mattero, Pablo and Rogulich, German. 2015.”Reconsideraciones sobre el perfil de la estructura de estratificación y la movilidad social intergeneracional desde las clases populares en Argentina a comienzos del siglo XXI." Revista Lavboratorio 15(26):255-80. Dalle, Pablo. 2016. Movilidad social desde las clases populares Un estudio sociológico en el Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires: CLACSO. -

SSA-2007-2008-1Hwc3no.Pdf

q eb r kfsbopfqv lc q eb r kfsbopfqv lc ` ef`^dl ` ef`^dl q eb p `elli lc p l`f^i p bosf`bp ^ ajfkfpqo^qflk q eb p `elli lc p l`f^i p bosf`bp OMMT=J=OMMU ^ ajfkfpqo^qflk ^ kklrk`bjbkqp OMMTJOMMU THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE SCHOOL of SOCIAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION ANNOUNCEMENTS Fall 2007 For information and application materials: Office of Admissions The School of Social Service Administration 969 E. 60th St. Chicago, IL 60637-2940 Telephone: 773-702-1492 [email protected] For information regarding field instruction: Office of Field Instruction Telephone: 773-702-9418 E-mail: [email protected] Callers who cannot get through on these numbers may leave a message with the School’s switchboard at 773-702-1250. For university residences information: Neighborhood Student Apartments The University of Chicago 5316 S. Dorchester Ave. Chicago, IL 60615 Telephone: 773-753-2218 International House 1414 E. 58th St. Chicago, IL 60637 Telephone: 773-753-2270 www.ssa.uchicago.edu 2007-2008 Volume XXVII The statements in these Announcements are subject to change without notice. TABLE of CONTENTS 1OFFICERS AND ADMINISTRATION 1 Officers of the University 1 Administration of the School 1 Officers of Instruction 2 Faculty Emeriti 3 Visiting Committee 5THE FIELD AND THE SCHOOL 5 The Field of Social Welfare 5 The School of Social Service Administration 6 The Mission of the School 7 The Educational Program 8 Professional Careers 8 The Broader Context 8 The University 9 The City 11 EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS 11 The Master of Arts Program 11 Student Educational Outcomes 12 The Core Curriculum 14 Field Placement 15 The Concentration Curriculum 15 Clinical Practice Concentration 18 Social Administration Concentration 21 Special Programs 25 Joint Degree Programs 27 Extended Evening Program 28 Doctoral Degree Program 28 Curriculum 29 Supports for Students 29 Requirements for the Ph.D. -

Uchicago Voices

T HE UNIVERSI T Y OF C HI C AGO S C HOOL OF SO C IAL SERVI C E A DMINIS T RA T ION A NNO U N C EMEN T S 2010-2011 sdfadsf THE UNIVERSITY OF CHI C AGO SC HOOL of SO C IAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION ANNO U N C EMEN T S Fall 2010 For information and application materials: Office of Admissions School of Social Service Administration 969 E. 60th St. Chicago, IL 60637-2940 Telephone: 773.702.1492 [email protected] For information regarding field instruction: Office of Field Education Telephone: 773.702.1178 Email: [email protected] Callers who cannot get through on these numbers may leave a message with the School’s switchboard at 773.702.1250. For University residences information: Neighborhood Student Apartments The University of Chicago 5316 S. Dorchester Ave. Chicago, IL 60615 Telephone: 773.753.2218 International House 1414 E. 58th St. Chicago, IL 60637 Telephone: 773.753.2270 www.ssa.uchicago.edu The information in the printed 2010-11 Announcements is current as of September 13, 2010. 2010-2011 VOLUME XXX The statements in these Announcements are subject to change without notice. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 OFFICERS AND ADMINISTRATION 1 Officers of the University 1 Administration of the School 1 Officers of Instruction 3 Faculty Emeriti 3 Visiting Committee 3 Life Members 4 THE FIELD AND T HE SC HOO L 4 The Field of Social Welfare 4 The School of Social Service Administration: A Concise History 4 The Mission Of The School 5 Goals 5 Combining Research with Practice 7 Development of Professional Social Workers and Social Work Researchers -

Ph.D. PROGRAM GRADUATES 2O2O – 2O21 the UNIVERSITY of CHICAGO | SCHOOL of SOCIAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION | Ph.D

Ph.D. PROGRAM GRADUATES 2O2O – 2O21 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO | SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION | Ph.D. PROGRAM 2020 – 2021 | TABLE OF CONTENTS | Dylan Bellisle ...........................................1 Bridgette Davis .........................................11 Kristen L. Ethier ......................................23 Katherine Ariel Gibson .............................33 Darnell Leatherwood ...............................42 Mina Lee ..................................................51 Hannah MacDougall ...............................57 Marion Malcome .....................................65 Tonie Sadler .............................................75 Angelica Velazquillo .................................84 Dylan Bellisle The aim of my research is to inequalities across the life examine the ways that public course. Ultimately, my goal programs and institutional is to inform the creation of practices align with the aspi- public policy that is responsive rations of low-income families. to the diversity of family life Through a critical lens that and provide valuable insight attends to race, class, and to social work students and gender, I use quantitative practitioners as they work with and qualitative methods to families through intergenera- examine the functioning of tional frameworks. public policy and its ability to mitigate social and economic 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO | SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION | Ph.D. PROGRAM 2020 – 2021 Dylan Bellisle 969 E 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637 708-299-5816 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. May 2021 (expected), University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration, Chicago, IL Dissertation Chair: Julia Henly, Ph.D. Committee: Marci Ybarra, Ph.D. Kristin Seefeldt, Ph.D. Dissertation Title: The Role of the Earned Income Tax Credit in Family Economic Decision Making: Moving Beyond an Individual Actor Model M.S.W. May 2011, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL Concentration: Community Health and Urban Development Summa Cum Laude B.A. -

Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President, Wilson Administration Records 1891-1978

University of Chicago Library Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President, Wilson Administration Records 1891-1978 © 2007 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Historical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 6 INVENTORY 6 Series I: General Files 6 Series II: Annual Reports 105 Series III: Correspondence 111 Series IV: University Budgets 114 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.OFCPRESWILSON Title University of Chicago. Office of the President. Wilson Administration. Records Date 1891-1978 Size 87.5 linear feet (169 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract This collection contains records of the University of Chicago Office of the President, covering the administration of John T. Wilson, who served as President from 1976-1978. Included are administrative records such as correspondence, reports, publications, budgets and personnel material. Information on Use Access Series I-III are open for research with no restrictions, beginning in 2008. Series IV, University Budgets, is restricted until 2028. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: University of Chicago. Office of the President. Wilson Administration. Records, [Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library Historical Note John Todd Wilson (1914-1990) received his A.B. degree with distinction from George Washington University in 1941 and an M.A. in 1942 from the State University of Iowa, studying psychology, philosophy, and education. During World War II, Wilson served in the U.S. -

Read the Full Magazine (PDF)

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO magazine SSAA PUBLICATION OF THE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION Supporting Parents The Latest Thinking about Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect VOLUME 14 | ISSUE 2 | FALL 2007 4 The Front Line in the War on Immigration 7 Hidden Costs of Witnessing Violence 8 Rethinking Crime and Addiction 16 The Incredible Strength of the Family 20 Can We Afford Public Service? magazine VOLUMEVOLUME 14 14| ISSUE| ISSUE 1 |2 SPRING| FALL 2007 SSA magazine SSA VOLUME 14 | ISSUE 2 DEAN Jeanne C. Marsh EDITORIAL BOARD Robert Chaskin, Chair William Borden Evelyn Brodkin E. Summerson Carr masthead Colleen Grogan Jennifer Mosley Stephen Gilmore (ex officio) 10 16 20 Tina Rzepnicki (ex officio) Maureen Stimming (ex officio) EDITOR Carl Vogel features 10 > COVER STORY: Protective Services We know more than ever before about how to prevent ASSISTANT EDITOR maltreatment of very young children. Brandie Egan DESIGN 16 > Close Support Anne Boyle, Boyle Design Associates Froma Walsh has become the leading advocate of the idea PHOTOGRAPHY that families can provide the strength to individuals to work Dan Dry through almost any trauma or adversity. Joan Hackett 20 > The High Cost of Giving Back Peter Kiar How can financial aid be fixed so graduate students can still Juliana Pino afford to work in public service? Marc PoKempner iStock Photography departments 2 > viewpoint: from the dean Insuring an SSA Education Susan Reich is Accessible to the Best and Brightest ShutterStock 4 > conversations In the Land of Immigrants EDITORIAL ADVISOR Melcher + Tucker Consultants 6 > ideas The Power of Stigma The shame of mental illness can SSA Magazine is published twice a derail clients already receiving treatment. -

Proquest:Proquest Research Library Accurate As of 17 August 2010 ‐ Coverage Dates Forma�Ed As MM/DD/YYYY

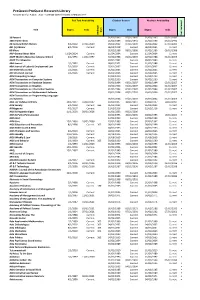

ProQuest:ProQuest Research Library Accurate as of 17 August 2010 ‐ Coverage dates formaed as MM/DD/YYYY Full Text Availability Citation Search Abstract Availability Title begins ends begins ends begins ends days embargo Peer‐reviewed 10 Percent 01/01/1993 07/01/1995 01/01/1993 07/01/1995 1001 Home Ideas 01/01/1988 06/01/1991 01/01/1988 06/01/1991 20 Century Brish History 3/1/2002 07/01/2009 03/01/2002 07/01/2009 03/01/2002 07/01/2009 • 401 (k) Advisor 6/1/1998 Current 06/01/1998 Current 06/01/2001 Current 80 Micro 01/01/1988 06/01/1988 01/01/1988 06/01/1988 AAP General News Wire 11/24/2004 Current 11/24/2004 Current 11/24/2004 Current AARP Modern Maturity; [Library edion] 2/1/1991 11/01/1997 02/01/1988 01/01/2003 02/01/1988 01/01/2003 AARP The Magazine 03/01/2003 Current 03/01/2003 Current ABA Journal 1/1/1992 Current 08/01/1972 Current 01/01/1988 Current • ABA Journal of Labor & Employment Law 7/1/2007 Current 07/01/2007 Current 07/01/2007 Current • ACI Materials Journal 1/1/2005 Current 01/01/2005 Current 01/01/2005 Current ACI Structural Journal 1/1/2005 Current 01/01/2005 Current 01/01/2005 Current • ACM Compung Surveys 12/01/1990 Current 12/01/1990 Current • ACM Transacons on Computer Systems 02/01/1999 Current 02/01/1999 Current • ACM Transacons on Database Systems 03/01/1994 03/01/2007 03/01/1994 03/01/2007 • ACM Transacons on Graphics 04/01/2004 01/01/2007 04/01/2004 01/01/2007 • ACM Transacons on Informaon Systems 01/01/2004 02/01/2007 01/01/2004 02/01/2007 • ACM Transacons on Mathemacal Soware 03/01/2004 03/01/2007 03/01/2004 03/01/2007 • ACM Transacons on Programming Languages and Systems 05/01/2004 01/01/2007 05/01/2004 01/01/2007 • ADA. -

SSA-2009-2010-1Pwmbtj.Pdf

T HE U NIVERSI T T HE UNIVERSI T Y OF Y OF C HI C AGO C HI C AGO S C HOOL OF S O C IAL S ERVI C E A DMINIS T RA T ION HOR. LOGO/ TRK 3/black 2009 - 2010 S C HOOL OF SO C IAL SERVI C E A DMINIS T RA T ION A NNO U N C EMEN T S 2009-2010 sdfadsf THE UNIVERSITY OF CHI C AGO SC HOOL of SO C IAL SERVICE ADMINISTRATION ANNO U N C EMEN T S Fall 2009 For information and application materials: Office of Admissions The School of Social Service Administration 969 E. 60th St. Chicago, IL 60637-2940 Telephone: 773.702.1492 [email protected] For information regarding field instruction: Office of Field Education Telephone: 773.702.9418 Email: [email protected] Callers who cannot get through on these numbers may leave a message with the School’s switchboard at 773.702.1250. For University residences information: Neighborhood Student Apartments The University of Chicago 5316 S. Dorchester Ave. Chicago, IL 60615 Telephone: 773.753.2218 International House 1414 E. 58th St. Chicago, IL 60637 Telephone: 773.753.2270 www.ssa.uchicago.edu The information in the printed 2009-10 Announcements is current as of September 10, 2009. 2009-2010 VOLUME XXIX The statements in these Announcements are subject to change without notice. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 OFFICERS and ADMINISTRATION 1 Officers of the University 1 Administration of the School 1 Officers of Instruction 3 Faculty Emeriti 3 Visiting Committee 3 Life Members 4 THE FIELD and the SC HOO L 4 The Field of Social Welfare 4 The School of Social Service Administration 5 The Mission Of The School 6 The -

The School of Social Service Administration

INTRODUCTION SSA faculty, staff, and returning students join in welcoming you to SSA and the University of Chicago. We hope that your time with us will be both satisfying and rewarding. This handbook provides current information about the School: its policies and practices. It should be used as a supplement to the Student Manual: University Policies and Regulations (http://studentmanual.uchicago.edu). The SSA Student Handbook does not repeat material in the University's Manual, nor information on curriculum, degree requirements, and other matters described in the School's Announcements. Doctoral students will also receive the Manual for Doctoral Students. In Autumn Quarter, an SSA Directory will be published and the new Announcements will be available. STUDENT HANDBOOK 2011-12 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Need to re-paginate depending on final format) THE MISSION OF THE SCHOOL ............................................................................ 1 GOVERNANCE OF THE SCHOOL ........................................................................... 3 STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE SCHOOL .......................................................... 4 REQUIRED AND ELECTIVE COURSES .................................................................... 4 GRADING AND EVALUATION .............................................................................. 6 I. Policy for Grading in SSA ...................................................................... 6 II. Appeal Procedures ............................................................................