Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mormon Studies Review Volume 4 Mormon Studies Review

Mormon Studies Review Volume 4 | Number 1 Article 25 1-1-2017 Mormon Studies Review Volume 4 Mormon Studies Review Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2 Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Review, Mormon Studies (2017) "Mormon Studies Review Volume 4," Mormon Studies Review: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 25. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2/vol4/iss1/25 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mormon Studies Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Review: <em>Mormon Studies Review</em> Volume 4 2017 MORMON Volume 4 STUDIES Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship REVIEW Brigham Young University Editor-in-chief J. Spencer Fluhman, Brigham Young University MANAGING EDITOR D. Morgan Davis, Brigham Young University ASSOCIATE EDITORS Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye, University of Auckland Benjamin E. Park, Sam Houston State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Michael Austin, Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, University of Evansville Philip L. Barlow, Leonard J. Arrington Chair of Mormon History and Culture, Utah State University Eric A. Eliason, Professor of English, Brigham Young University Kathleen Flake, Richard L. Bushman Chair of Mormon Studies, University of Virginia Terryl L. Givens, James A. Bostwick Chair of English and Professor of Literature and Religion, University of Richmond Matthew J. Grow, Director of Publications, Church History Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Grant Hardy, Professor of History and Religious Studies, University of North Carolina–Asheville David F. -

Narrating Jane: Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Arrington Annual Lecture Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures 9-24-2015 Narrating Jane: Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman Quincy D. Newell Hamilton College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_lecture Part of the History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Newell, Quincy D., "Narrating Jane: Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman" (2015). 21st annual Arrington Lecture. This Lecture is brought to you for free and open access by the Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arrington Annual Lecture by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEONARD J. ARRINGTON MORMON HISTORY LECTURE SERIES No. 21 Narrating Jane Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman by Quincy D. Newell September 24, 2015 Sponsored by Special Collections & Archives Merrill-Cazier Library Utah State University Logan, Utah Newell_NarratingJane_INT.indd 1 4/13/16 2:56 PM Arrington Lecture Series Board of Directors F. Ross Peterson, Chair Gary Anderson Philip Barlow Jonathan Bullen Richard A. Christenson Bradford Cole Wayne Dymock Kenneth W. Godfrey Sarah Barringer Gordon Susan Madsen This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-1-60732-561-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60732-562-8 (ebook) Published by Merrill-Cazier Library Distributed by Utah State University Press Logan, UT 84322 Newell_NarratingJane_INT.indd 2 4/13/16 2:56 PM Foreword F. -

Joseph Smith Period Clothing 145

Carma de Jong Anderson: Joseph Smith Period Clothing 145 Joseph Smith Period Clothing: The 2005 Brigham Young University Exhibit Carma de Jong Anderson Early in 2005, administrators in Religious Education at Brigham Young University gave the green light to install an exhibit (hopefully my last) in the display case adjacent to the auditorium in the Joseph Smith Building. The display would showcase the clothing styles of the life span of the Prophet Joseph Smith and the people around him (1805–1844). There were eleven mannequins and clothing I had constructed carefully over many years, mingled with some of my former students’ items made as class projects. Those pieces came from my teaching the class, “Early Mormon Clothing 1800–1850,” at BYU several years ago. There were also a few original pieces from the Joseph Smith period. During the August 2005 BYU Education Week, thousands viewed these things, even though I rushed the ten grueling days of installation for something less than perfect.1 There was a constant flow of university students passing by and stopping to read extensive signage on all the contents shown. Mary Jane Woodger, associate professor of Church History and Doctrine, reported more young people and faculty paid attention to it than any other exhibit they have ever had. Sincere thanks were extend- ed from the members of Religious Education and the committee plan- ning the annual Sydney B. Sperry October symposium. My scheduled lectures to fifteen to fifty people, two or three times a week, day or night for six months (forty stints of two hours each), were listened to by many of the thirty thousand viewers who, in thank-you letters, were surprised at how much information could be gleaned from one exhibit. -

MAX PERRY MUELLER University of Nebraska-Lincoln/Department of Classics and Religious Studies 337-254-7552 • [email protected]

MAX PERRY MUELLER University of Nebraska-Lincoln/Department of Classics and Religious Studies 337-254-7552 • [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Ph.D., June, 2015, The Committee on the Study of Religion (American religious history). Dissertation: “Black, White, and Red: Race and the Making of the Mormon People, 1830- 1880.” Committee: David Hempton (co-chair), Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (co-chair), Marla Frederick, David Holland. Comprehensive Exams specializations (with distinction): Native American Religious History and African-American Religious History Secondary Doctoral Field, 2013, African and African American Studies. Harvard Divinity School, Cambridge, MA M.T.S., 2008, Harvard Divinity School. Carleton College, Northfield, MN B.A., 2003, magna cum laude. Double major in Religion (Distinction in major) and French and Francophone Studies (Distinction in major). PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2016-Present The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Department of Classics and Religious Studies, Assistant Professor. Fellow in the Center for Great Plains Studies Affiliated with the Institute for Ethnic Studies 2015-2016 Amherst College, Religion Department, Visiting Assistant Professor. 2014-2015 Mount Holyoke College, Religion Department, Visiting Lecturer. Fall 2013 Carleton College, Religion Department, Visiting Lecturer. 2010-2013 Harvard University, Teaching Fellow and Tutor. 2003-2006 Episcopal School of Acadiana (Lafayette, LA), Upper School French Teacher and Head Cross-Country and Track Coach (boys and girls). 1 PUBLICATIONS Book Projects Race and the Making of the Mormon People, 1830-1908. The University of North Carolina Press, 2017. * Winner of John Whitmore Historical Association, Best Documentary Book (2018) Reviewed in: The Atlantic, Harvard Divinity School Bulletin, Choice, Reading Religion, Church History, Nova Religio, BYU Studies Quarterly, The Journal of Mormon History, Mormon Studies Review, Western History Quarterly, American Historical Review, Utah Historical Quarterly, among others. -

Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 47 Issue 2 Article 1 4-1-2008 Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood Edward L. Kimball Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Kimball, Edward L. (2008) "Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 47 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol47/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Kimball: Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood President Spencer W. Kimball spent many hours alone, pondering and praying, as he sought revelation on the priesthood question. Courtesy Church History Library. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2008 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 47, Iss. 2 [2008], Art. 1 Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood Edward L. Kimball o doubt the most dramatic moment of the Spencer W. Kimball N administration and probably the highlight of Church history in the twentieth century occurred in June 1978, when the First Presidency announced a revelation allowing worthy men of all races to be ordained to the priesthood and allowing worthy men and women access to all temple ordinances. The history of this issue reaches back to the early years of the Church. Without understanding the background, one cannot appreciate the magnitude of the 1978 revelation. When the Church was very young a few black men were ordained to the priesthood. -

Max Perry Mueller CV 2020

MAX PERRY MUELLER University of Nebraska-Lincoln/Department of Classics and Religious Studies 337-254-7552 • [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Ph.D., June, 2015, The Committee on the Study of Religion (American religious history). Dissertation: “Black, White, and Red: Race and the Making of the Mormon People, 1830- 1880.” Committee: David Hempton (co-chair), Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (co-chair), Marla Frederick, David Holland. Comprehensive Exams specializations (with distinction): Native American Religious History and African-American Religious History Secondary Doctoral Field, 2013, African and African American Studies. Harvard Divinity School, Cambridge, MA M.T.S., 2008, Harvard Divinity School. Carleton College, Northfield, MN B.A., 2003, magna cum laude. Double major in Religion (Distinction in major) and French and Francophone Studies (Distinction in major). PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2016-Present The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Department of Classics and Religious Studies, Assistant Professor. Fellow in the Center for Great Plains Studies Affiliated with the Institute for Ethnic Studies (applied) 2015-2016 Amherst College, Religion Department, Visiting Assistant Professor. 2014-2015 Mount Holyoke College, Religion Department, Visiting Lecturer. Fall 2013 Carleton College, Religion Department, Visiting Lecturer. 2010-2013 Harvard University, Teaching Fellow and Tutor. 2003-2006 Episcopal School of Acadiana (Lafayette, LA), Upper School French Teacher and Head Cross-Country and Track Coach (boys and girls). 1 PUBLICATIONS Book Projects Race and the Making of the Mormon People, 1830-1908. The University of North Carolina Press, 2017. * Winner of John Whitmore Historical Association, Best Documentary Book (2018) Reviewed in: The Atlantic, Harvard Divinity School Bulletin, Choice, Reading Religion, Church History, Nova Religio, BYU Studies Quarterly, The Journal of Mormon History, Mormon Studies Review, Western History Quarterly, American Historical Review, Utah Historical Quarterly, among others. -

Dated They Be Enemies. the Gospel of Jesus Christ Required They Be Friends. on the Eve of the Death of Joseph Smith, His Widow, Emma, Is on the Brink of Destruction

Two women. One white. The other black. Society man- dated they be enemies. The gospel of Jesus Christ required they be friends. On the eve of the death of Joseph Smith, his widow, Emma, is on the brink of destruction. In order to stand with her friend in her darkest hour, one woman, Jane Manning, will need to hear the voice of God once more. Can she hear His voice again? And if so, can she find the strength to abide it? Danielle Deadwyler Emily Goss (Emma Smith) (Jane Manning James) Emily Goss is a film, television, and the- Danielle Deadwyler is a congregation of ar- atre actress. Her work in the psychological tistic personas and firebrand talent. Her so- horror indie hit “The House On Pine Street” phisticated spunk and ingenuity is reflected earned her 3 awards, and she has now won 5 on stages, screens, and pages. The Atlanta awards for her portrayal of the bold, charis- native is best known for her roles in Gifted, matic Louise in the period romance “Snap- The Leisure Seeker and Atlanta. shots.” Emily got her BA in Theatre from the USC’s School of Dramatic Art, and Brad Schmidt (Joseph Smith) Masters in Classical Acting from LAMDA Brad Schmidt was born on May 31, 1979 in (London Academy of Music and Dramatic Cleveland, Ohio, USA. He is known for his Art). A California native, she grew up play- work on The Birth of a Nation (2016), Here ing soccer and climbing trees. Emily is now and Now (2018) and House of Lies (2012). -

Mormonism's Negro Doctrine

LOOKING BACK, LOOKING FORWARD: “MORMONISM’S NEGRO DOCTRINE” FORTY-FIVE YEARS LATER1 Lester E. Bush, Jr. It has been forty-five years since Dialogue published my essay entitled “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview”2 and forty years since Official Declaration 2 ended the priesthood/temple ban. It seems like a good time to take stock of where we are: what has changed, what has stayed the same, what changes still need to happen, and what steps need to occur to bring about those changes. What’s New The first task—what has changed—is in some ways the easiest, and certainly the most uplifting. Almost everything has changed, and all for the good, beginning with the “priesthood revelation” of 1978. The obvious milestones, aside from the revelation itself, are: • the immediate ordination of Blacks to the priesthood, soon includ- ing the office of high priest, and the resumption of temple ordinances • just twelve years after the revelation, the first Black General Authority was called; recently, two more were called 1. A version of these remarks was originally given as the Sterling M. McMurrin Lecture on Religion and Culture at the University of Utah on October 8, 2015. 2. Lester E. Bush, Jr., “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 8, no. 1 (Spring 1973): 11–68. 1 2 Dialogue, Fall 2018 • an inner city proselyting effort began • African American stake presidents were called in the Deep South • the growth of the Black membership from perhaps a few thousand to somewhere over half a million Africa deserves special mention. -

SWEET FREEDOM's PLAINS: African Americans on the Overland Trails

SWEET FREEDOM’S PLAINS: African Americans on the Overland Trails 1841-1869 By Shirley Ann Wilson Moore, PhD. For the National Park Service National Trails Intermountain Region Salt Lake City & Santa Fe January 31, 2012 ii The Flying Slave The night is dark, and keen the air, And the Slave is flying to be free; His parting word is one short prayer; O God, but give me Liberty! Farewell – farewell! Behind I leave the whips and chains, Before me spreads sweet Freedom’s plains --William Wells Brown The Anti-Slavery Harp: A Collection of Songs For Anti-Slavery Meetings, 1848 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures and Maps iv Preface vii Acknowledgments xvi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Race, Slavery, and Freedom 4 Chapter 2: The Jumping-Off Places 40 Chapter 3: The Providential Corridor 66 Chapter 4: Sweet Freedom’s Plains 128 Chapter 5: Place of Promise 176 Appendix: Figures and Maps 215 Bibliography 267 iv LIST OF FIGURES AND MAPS Photographs and Illustrations York in the Camp of the Mandans 216 Victory Hymn for Archy Lee 217 Dred Scott and Harriet Scott 218 Westport, Missouri, ca. 1858 220 Independence, Missouri, 1853 221 Emily Fisher, Her Final Resting Place 222 Possibly a Hiram Young Wagon, Independence, Missouri, ca. 1850 223 Hiram and Matilda Young’s Final Resting Place 224 James P. Beckwourth 232 Moses “Black” Harris, ca. 1837 233 Elizabeth “Lizzy” Flake Rowan, ca 1885 234 Green Flake 235 Edward Lee Baker, Jr. 236 Rose Jackson 237 Grafton Tyler Brown 238 Guide Book of the Pacific, 1866 239 Fort Churchill, Nevada Territory 240 Black Miner, Spanish Flat, California, 1852 241 Black Miner, Auburn Ravine, California, 1852 242 George W. -

Sample PDF of Curse of Cain? Racism in the Mormon Church

Sample Curse of Cain? Racism in the Mormon Church By Jerald and Sandra Tanner Curse of Cain? Racism in the Mormon Church by Jerald and Sandra Tanner Utah Lighthouse Ministry 1358 S. West Temple Salt Lake City, UT 84115 www.utlm.org Curse of Cain? USER LICENSING AGREEMENT This digital book is in Adobe’s PDF format. Purchasing grants one user license for the digital book. The digital book may not be resold, altered, copied for another person, or hosted on any server without the express written permission of Utah Lighthouse Ministry. The purchaser is free to copy the digital book to any device for their own personal and non-commercial use only. © 2013 Utah Lighthouse Ministry, Inc. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Racism in the Book of Mormon ...................................................... 6 Who are the Lamanites? .................................................................. 7 Dark and Loathsome? ..................................................................... 7 Lamanites and DNA ........................................................................ 9 Israelites and Gentiles ................................................................... 11 Book of Moses .............................................................................. 11 Trouble in Missouri ....................................................................... 11 Abolitionists .................................................................................. 14 Book of Abraham ......................................................................... -

Elijah Abel and the Changing Status of Blacks Within Mormonism

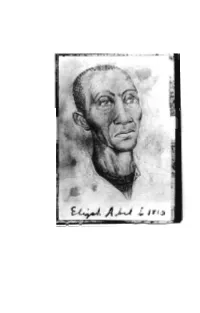

ELIJAH ABEL AND THE CHANGING STATUS OF BLACKS WITHIN MORMONISM NEWELL G. BRINGHURST ON THE SURFACE it was just another regional conference for the small but troubled Cincinnati branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on a summer day in June 1843. Not unlike other early branches of the Church, the Cincinnati congregation had a number of problems, including internal dissension and just plain "bad management." Presiding over this conference was a "Traveling High Council" consisting of three Mormon apostles.1 As the visiting council probed the difficulties plaguing the Cincinnati Saints, its attention was drawn to the activities of Elijah Abel, a unique member of the branch. Abel, a black Mormon Priesthood holder, found himself under fire because of his visibility as a black Mormon. Apostle John E. Page maintained that while "he respects a coloured Bro, wisdom forbids that we should introduce [him] before the public." Apostle Orson Pratt then "sustained the position of Bro Page" on this question. Apostle Heber C. Kimball also expressed concern about this black priesthood holder's activities. In response, Abel "said he had no disposition to force himself upon an equality with white people." Toward the end of the meeting, a resolution was adopted restricting Abel's activities. To conform with the established "duty of the 12 ... to ordain and send men to their native country Bro Abels [sic] was advised to visit the coloured population. The advice was sanctioned by the conference. Instructions were then given him concerning his mission."2 This decision represents an important turning point not only for Elijah Abel but for all Mormon blacks. -

Blacks and Priesthood: 40 Years Later

salt lake city messenger June 2018 Issue 130 Editor: Sandra Tanner Utah Lighthouse Ministry 1358 S. West Temple Salt Lake City, UT 84115 www.utlm.org BLACKS AND PRIESTHOOD: 40 YEARS LATER “for the seed of Cain were black and had not place among them.” Pearl of Great Price, Moses 7:22 “We have pleaded long and earnestly in behalf of Even though two or three blacks had been baptized these, our faithful brethren,” wrote Spencer W. Kimball and ordained to the priesthood during the lifetime of in the announcement of June 8, 1978, when the Church Joseph Smith this did not grant them access to the secret of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints lifted the ban on LDS temple rituals, thus barring them from the Mormon blacks holding their priesthood, now published as Official goal of eternal marriage and advancement to godhood. Declaration 2 in the Doctrine and Covenants. According to KSL.com, on Friday, June 1, ELIJAH ABEL 2018, the LDS Church will hold a celebration of the 40th anniversary The most well-known black to hold of granting priesthood to blacks. the priesthood during Smith’s Along with a message from the lifetime was Elijah Abel, a First Presidency of the LDS Seventy, who moved to Utah Church, two famous black territory with the pioneers. singers, Gladys Knight and LDS historian Andrew Alex Boyé will be included Jenson made note of Abel’s in the event. Ms. Knight ordination: joined Mormonism in 1997 Abel, Elijah, the only colored and Mr. Boyé has sung with man who is known to have been the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.1 ordained to the priesthood .