Free PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Colorado River Project: Is New Hydropower Development the Key to a Renewable Energy Future, Or the Vestige of a Failed Past?

COLORADO NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REVIEW The Little Colorado River Project: Is New Hydropower Development the Key to a Renewable Energy Future, or the Vestige oF a Failed Past? Liam Patton* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 42 I. THE EVOLUTION OF HYDROPOWER ON THE COLORADO PLATEAU ..... 45 A. Hydropower and the Development of Pumped Storage .......... 45 B. History of Dam ConstruCtion on the Plateau ........................... 48 C. Shipping ResourCes Off the Plateau: Phoenix as an Example 50 D. Modern PoliCies for Dam and Hydropower ConstruCtion ...... 52 E. The Result of Renewed Federal Support for Dams ................. 53 II. HYDROPOWER AS AN ALLY IN THE SHIFT TO CLEAN POWER ............ 54 A. Coal Generation and the Harms of the “Big Buildup” ............ 54 B. DeCommissioning Coal and the Shift to Renewable Energy ... 55 C. The LCR ProjeCt and “Clean” Pumped Hydropower .............. 56 * J.D. Candidate, 2021, University oF Colorado Law School. This Note is adapted From a final paper written for the Advanced Natural Resources Law Seminar. Thank you to the Colorado Natural Resources, Energy & Environmental Law Review staFF For all their advice and assistance in preparing this Note For publication. An additional thanks to ProFessor KrakoFF For her teachings on the economic, environmental, and Indigenous histories of the Colorado Plateau and For her invaluable guidance throughout the writing process. I am grateFul to share my Note with the community and owe it all to my professors and classmates at Colorado Law. COLORADO NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REVIEW 42 Colo. Nat. Resources, Energy & Envtl. L. Rev. [Vol. 32:1 III. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF PLATEAU HYDROPOWER ............... -

FACT SHEET OVERVIEW Lower Cliff Dwelling Construction Sequence

southwestlearning.org TONTO Lower Cliff Dwelling FACTOVERVIEW SHEET Construction Sequence ARCHIVES SERVICE PARK NATIONAL Tonto National Monument, established in 1907, protects several cliff dwelling sites and numerous smaller archeo- logical sites scattered throughout the highlands and allu- vial plains within the Tonto Basin, Arizona. The Lower Cliff Dwelling is one of two large sites accessible to the public, and is the primary site visited in the Monument throughout the year. Background The Lower Cliff Dwelling consists of an approximately 20- room masonry and adobe village built within a natural al- cove above a side drainage of the Salt River called Cholla Canyon and overlooking Cave Canyon, where there is now an active spring. The site itself has been known since at The Lower Cliff Dwelling at Tonto National Monument, ca. 1905. least the late 1800s, and unfortunately, was subject to exces- sive looting and associated damage long before becoming a lage was not built all at once, however, and instead started Monument in 1907 and later coming under the protection of with only one or two rooms, to which additional rooms the National Park Service (NPS) in 1933. However, histor- were added over a period of perhaps 30 years (Nordby et ic photographs, excavation and stabilization records (e.g., al. 2012). New rooms were built on bedrock, artificially Duffen 1937; Pierson 1952), and recent research provide leveled floors, and accumulated trash. While the rocks and some indication of when and how the Lower Cliff Dwelling clay for the adobe were readily available (Nordby et al. was constructed, and to some extent, by whom. -

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

Sedona/Verde Valley Mental Health Resources Guide

SEDONA/VERDE VALLEY MENTAL HEALTH RESOURCES GUIDE This resource guide has been compiled to help people obtain information and select various mental health and other related treatment and support services in the Sedona/Verde Valley communities. Sedona / Verde Valley Mental Health Resources Guide This Mental Health Resources Guide is a partnership production of NAMI Sedona, the Mental Health Coalition Verde Valley, and Spectrum Healthcare (formerly Verde Valley Guidance Clinic). The main focus of this Guide is to provide mental health resources in the Sedona / Verde Valley areas. Please note that the Guide includes some resources in Prescott and Flagstaff as well as at the Arizona state and federal level. This is because these resources are not available in the Sedona/Verde Valley communities. The Table of Contents on page 3 provides the various categories of services and the corresponding page numbers where these resources can be found in the Guide. Inclusion in this Guide should in no way be construed to constitute an endorsement of a practitioner, an agency, organization, or its service, nor should exclusion be construed to constitute disapproval. It is up to a person using these resources to determine if they offer something needed and whether or not they are appropriate for a particular situation. Emergency/crisis phone numbers are also provided on this page, as follows: Crisis Contact Numbers: Spectrum Healthcare (formerly Verde Valley Guidance Clinic): For immediate emergency, call 911. For other crisis situations, call Spectrum Healthcare at 928-634- 2236, available 24/7. NAZCARE: If you feel like you just need to talk to someone, call the NAZCARE Warmline at 1-888-404-5530, or 928-649-3771; the staff is available from 5:00 to 10:30 p.m., 7 days a week, including holidays. -

Tribal Higher Education Contacts.Pdf

New Mexico Tribes/Pueblos Mescalero Apache Contact Person: Kelton Starr Acoma Pueblo Address: PO Box 277, Mescalero, NM 88340 Phone: (575) 464-4500 Contact Person: Lloyd Tortalita Fax: (575) 464-4508 Address: PO Box 307, Acoma, NM 87034 Phone: (505) 552-5121 Fax: (505) 552-6812 Nambe Pueblo E-mail: [email protected] Contact Person: Claudene Romero Address: RR 1 Box 117BB, Santa Fe, NM 87506 Cochiti Pueblo Phone: (505) 455-2036 ext. 126 Fax: (505) 455-2038 Contact Person: Curtis Chavez Address: 255 Cochiti St., Cochiti Pueblo, NM 87072 Phone: (505) 465-3115 Navajo Nation Fax: (505) 465-1135 Address: ONNSFA-Crownpoint Agency E-mail: [email protected] PO Box 1080,Crownpoint, NM 87313 Toll Free: (866) 254-9913 Eight Northern Pueblos Council Fax Number: (505) 786-2178 Email: [email protected] Contact Person: Rob Corabi Website: http://www.onnsfa.org/Home.aspx Address: 19 Industrial Park Rd. #3, Santa Fe, NM 87506 (other ONNSFA agency addresses may be found on the Phone: (505) 747-1593 website) Fax: (505) 455-1805 Ohkay Owingeh Isleta Pueblo Contact Person: Patricia Archuleta Contact Person: Jennifer Padilla Address: PO Box 1269, Ohkay Owingeh, NM 87566 Address: PO Box 1270, Isleta,NM 87022 Phone: (505) 852-2154 Phone: (505) 869-9720 Fax: (505) 852-3030 Fax: (505) 869-7573 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.isletapueblo.com Picuris Pueblo Contact Person: Yesca Sullivan Jemez Pueblo Address: PO Box 127, Penasco, NM 87553 Contact Person: Odessa Waquiu Phone: (575) 587-2519 Address: PO Box 100, Jemez Pueblo, -

Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Arizona Contact Information For more information about the Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 435-688-3226 or write to: Superintendent, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, 345 E. Riverside Drive, St. George, UT 84790 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument resources and values are important enough to merit designation as a national monument. Statements of significance describe the distinctive nature of the monument and why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. They focus on the most important resources and values that will assist in planning and management for the monument. • Spanning 320 million years, the exposed rock layers at Parashant National Monument provide a distinctly identifiable view of the geologic boundaries of the Colorado Plateau and Basin and Range regions, including evidence of the interaction between volcanic processes and native cultural communities. The extensive natural history reveals a robust fossil record and preserves museum-quality marine and ice age fossils. At GRAND CANYON-PARASHANT NATIONAL • Encompassing more than 1 million acres, a dramatic MONUMENT, the Bureau of Land elevational gradient from 1,200 to 8,000 feet, and transitional Management and the National zones of the Sonoran, Mojave, Great Basin, and Colorado Park Service cooperatively protect Plateau ecoregions, Parashant National Monument protects undeveloped, wild, and remote a biologically rich system of plant and animal life. northwestern Arizona landscapes • Parashant National Monument is one of the most rugged and their resources, while providing and remote landscapes remaining in the southwestern opportunities for solitude, primitive United States. -

New Mexico Archaeology New Mexico Archaeology

NTheNew ewNewsletter MMexicoexico of the Friends AArchaeology rchaeologyof Archaeology November 2014 From The Director Pottery on the web Eric Blinman Ph.D, Director OAS Office of Archaeological Studies is delighted to an- I’m writing this with the knowledge that I have yet again nounce the launch of a new research tool and valuable violated Jessica’s trust in me in her role as editor. My deadline addition to our website. The Pottery Typology Project, for producing this column was last week, but in the press created by C. Dean Wilson is an online compendium of of responsibility and opportunity there’s been no time until the Native pottery of New Mexico found in archaeologi- now. In some senses, my procrastination has been fortunate, cal context. since the week has been intense and reorienting, and Jessica’s patience is just one of many reminders of how fortunate we all are to have each other. The Friends of Archaeology and OAS both work, and probably work so well together, because there is an underlying passion for and commitment to the subject matter and potential of archaeology. This attitude leads to effort above and beyond any reasonable expectation from both staff and volunteers. Jessica and her volunteers have put up with a lot of stress caused by the rest of us in their journey to produce each of the newsletters, and the results are easy to both appreciate and take for granted. Sheri worked hard, with only inconsistent support from me, to pull together the logistics Why is a pottery typology on line important? Since the of the wonderfully successful Canyon of the Ancients tour. -

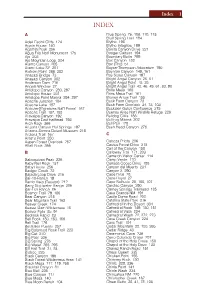

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

Southern Sinagua Sites Tour: Montezuma Castle, Montezuma

Information as of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center Presents: March 4, 2021 99 a.m.-5:30a.m.-5:30 p.m.p.m. SouthernSouthern SinaguaSinagua SitesSites Tour:Tour: MayMay 8,8, 20212021 MontezumaMontezuma Castle,Castle, SaturdaySaturday MontezumaMontezuma Well,Well, andand TuzigootTuzigoot $30 donation ($24 for members of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center or Friends of Pueblo Grande Museum) Donations are due 10 days after reservation request or by 5 p.m. Wednesday May 8, whichever is earlier. SEE NEXT PAGES FOR DETAILS. National Park Service photographs: Upper, Tuzigoot Pueblo near Clarkdale, Arizona Middle and lower, Montezuma Well and Montezuma Castle cliff dwelling, Camp Verde, Arizona 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday May 8: Southern Sinagua Sites Tour – Montezuma Castle, Montezuma Well, and Tuzigoot meets at Montezuma Castle National Monument, 2800 Montezuma Castle Rd., Camp Verde, Arizona What is Sinagua? Named with the Spanish term sin agua (‘without water’), people of the Sinagua culture inhabited Arizona’s Middle Verde Valley and Flagstaff areas from about 6001400 CE Verde Valley cliff houses below the rim of Montezuma Well and grew corn, beans, and squash in scattered lo- cations. Their architecture included masonry-lined pithouses, surface pueblos, and cliff dwellings. Their pottery included some black-on-white ceramic vessels much like those produced elsewhere by the An- cestral Pueblo people but was mostly plain brown, and made using the paddle-and-anvil technique. Was Sinagua a separate culture from the sur- rounding Ancestral Pueblo, Mogollon, Hohokam, and Patayan ones? Was Sinagua a branch of one of those other cultures? Or was it a complex blending or borrowing of attributes from all of the surrounding cultures? Whatever the case might have been, today’s Hopi Indians consider the Sinagua to be ancestral to the Hopi. -

2010 General Management Plan

Montezuma Castle National Monument National Park Service Mo n t e z u M a Ca s t l e na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t • tu z i g o o t na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t Tuzigoot National Monument U.S. Department of the Interior ge n e r a l Ma n a g e M e n t Pl a n /en v i r o n M e n t a l as s e s s M e n t Arizona M o n t e z u MONTEZU M A CASTLE MONTEZU M A WELL TUZIGOOT M g a e n e r a l C a s t l e M n a n a g e a t i o n a l M e n t M P o n u l a n M / e n t e n v i r o n • t u z i g o o t M e n t a l n a a t i o n a l s s e s s M e n t M o n u M e n t na t i o n a l Pa r k se r v i C e • u.s. De P a r t M e n t o f t h e in t e r i o r GENERAL MANA G E M ENT PLAN /ENVIRON M ENTAL ASSESS M ENT General Management Plan / Environmental Assessment MONTEZUMA CASTLE NATIONAL MONUMENT AND TUZIGOOT NATIONAL MONUMENT Yavapai County, Arizona January 2010 As the responsible agency, the National Park Service prepared this general management plan to establish the direction of management of Montezuma Castle National Monument and Tu- zigoot National Monument for the next 15 to 20 years. -

Introduction

City of Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines CHAPTER 1 Introduction • Philosophy of the Design Guidelines • How to Use the Design Guidelines • Submittal Process Chapter 1: Introduction City of Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines Chapter 1: Introduction City of Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines Chapter 1: Introduction Philosophy of the Design Guidelines The Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines provide a basis for evaluating building design proposals within the District and help ensure implementation of the goals of the Historic Preservation Ordinance. The Guidelines have been derived from the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Treat- ment of Historic Properties and are specifi cally crafted to meet the needs of the City of Manitou Springs, Colorado. The Guidelines require reasonable application. Their purpose in the design approval process is to maintain and protect: • The historic integrity of individual structures and historic features in the District • The unique architectural character of the different sub-districts • The distinctiveness of the city as a whole The Guidelines provide a tool for property owners and the Commission to use in determining whether a proposal is appropriate to the long-term interests of the District. The parameters set forth in the Guidelines also support opportunities for design creativity and individual choice. Our application of the Guidelines encourages a balance between function and preservation, accommodating the needs of property -

PUEBLO SETTLEMENTS NEAR EL PASO, TEXAS 59 Terially the Population

·.~ . ' . .: Jt:." ... ~. :-;;, ...: ~ • : n e&:·r na·t'tes «Ct .,. d··=' ,. -:;, .. ~ -., .,.....,,,,>- <*w· .... \ -· . .._.... ~.----·-·--~-- - d " ,,,z•=t' .. ;_. ,. l • '.· r ~l THE PUEBLO SETTLEMENTS NEAR " EL PASO, TEXAS ... ,. BY J. WALTER FEWKES • ~. '· ,.v. rt ;... i I t (N. 1 .. (From the Americaa Aathropoloitlat •.),Vol. 41 No. 1 January-March, r902j ,·I i-~'. ;.• f '. i' •.,, r- • ' f: .. ·. : . ·. I I .- ..'· ~. i< l - I•· . NEW YORK j· . G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS ~ ..... .:~. ' / ......... I ~- \•'. .·. ~ ·:·. .... ~ . ' . --· . ..:? .................... .. .. ~j...::.. :..~.::·'~··.·.ji.:~.: ··.~~ ....:... ..... ·-·~~ . ..., . : .\ .. -~· ~ : . /. , . .. -... .. _... -··•. .«....... ~·1i...ia· ... • : • ·-· ... , •.• · .......... rnntA N.r,LAIMS COMMISSION THE PUEBLO SE.TTLE~tENTS NEAR EL PASO, TEXAS Bv ]. \V:\ L TER FE WK.ES On a map of the " Reino de la N ueua Mexico," made by Father Menchero about 1747, 1 five pueblos are figured on the right bank of the Rio Grande, below the site of the present city of El Paso, Texas. One of these, called in the legend, Presidio dcl Paso, is situated where Juarcz, in Chihuahua, now stands, just opposite El Paso. The other four arc designated on this map as 1 Mision d 5" Lorenzo, Mision d Cenecu, Mision d la Isleta, and Mision del Socorro. Each is indicated by a picture of a church building, with surrounding lines representing irrigation canals, as the legend "riego de las misiones" states. All of these lie on the right bank of the river, or in what is now the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. It is known Crom historical sources that Indians speak. ing at least four different dialects, and probably comprising three distinct stocks, inhabited these fi\•e towns. The Mansos lived in El Paso, the Suma in San Lorenzo, the Tiwa in Ysleta, and the Piros in Senecu and Socorro; there were also other Indians - Tano, Tewa, and Jemez - scattered through some of these set tlemen-ts.