Trade Marks Opposition Decision (O/118/00)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gigi Hadid Photographed by Helena Christensen Exclusively for the May 2019 Issue of Vogue Czechoslovakia

Gigi Hadid photographed by Helena Christensen exclusively for the May 2019 issue of Vogue Czechoslovakia The May issue of VOGUE CS features a photo shoot with one of the most sought after models in the world - Gigi Hadid. It is the first time Gigi has invited a magazine to her family farm located near New York. Helena Christensen, the Danish supermodel and icon of the nineties - who is also a successful photographer, shot the American model there for the Czechoslovak edition of the world‘s most important fashion magazine. Gigi wore clothes from several Czech fashion designers throughout the cover story. “I am delighted that thanks to the friendship of Eva Herzigova, Helena Christensen and Gigi Hadid, we could photograph Gigi in her secret place, where she has not yet invited any other photographer or jour- nalist. We tried to show Gigi as she’s never been seen before, with her horses, in a place she loves,” says Andrea Běhounková, Editor-in-Chief of Vogue CS. “I wanted her to be as much of herself as possible on her farm among horses, surrounded by nature. Gigi finds not only inspiration, but above all peace and security, in this environment. I wanted to capture her essence, the little girl that still remains in her. The wind blows in her hair, her eyes are full of expectations that something special will happen,” says Helena Christensen. Gigi Hadid personally invited Helena Christensen and the Vogue CS team to her farm located near New York which she shares with her mother and siblings. To capture the intimate and dreamlike atmosphere of the place, Helena Christensen combined digital photography with expired Polaroids. -

To Enjoy the Exhibition Catalog

BEYOND BEAUTY ELLEN VON UNWERTH BEYOND BEAUTY Beauty thrives on diversity and is in the eye of the beholder. A universal ideal of beauty has long since ceased to exist and yet we still have the ‘women of one’s dreams’, who, with their personality and beauty, have become icons of our time. Preiss Fine Arts will be presenting numerous works of famous photographers of our time within the topic of feminine beauty – in a manner that is both varied and charged with tension. Instead of being limited to superficial stereotypes, the character of the women portrayed is placed at the centre of attention. Different artistic styles are open to inter- pretation. The result is a combination of charismatic portraits and intimate studies of the female body, which are, by no means, devoted to only clichés. Multi-faceted studies of women, which transfix the viewer with self-confidence, personality and strength will be shown. ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH The Tramp, Eva Herzigova Meow, Jessica Chastain ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH Claudia Schiffer Bedazzled, Lindsay Wixson, Paris, 2015 From the Story of Olga ARTHUR ROXANNE ELGORT LOWIT ARTHUR ELGORT ROXANNE LOWIT ROXANNE LOWIT Christy Turlington Iman Kristen McMenamy, Paris ARTHUR ELGORT ROXANNE LOWIT Kate Moss in Nepal Linda Evangelista, Naomi Campbell, Christy Turlington,Speaking, hearing and seeing no evil DAVID SYLVIE DREBIN BLUM DAVID DREBIN Mermaid in Paradise SYLVIE BLUM The Group, 2008 MICHEL COMTE MICHEL COMTE MICHEL COMTE Beauty and Beast with Snake Supermodels MICHEL COMTE MICHEL COMTE MICHEL COMTE Carla Bruni Helena Christensen 3 Gisele Bündchen ALBERT GUIDO WATSON ARGENTINI ELLEN VON UNWERTH Kate Moss and David Bowie, New York, 2003 ALBERT WATSON GUIDO ARGENTINI Monica Gripman Candice thinking about tomorrow ALBERT WATSON ALBERT WATSON GUIDO ARGENTINI Naomi Campbell Monkey Series – Monkey King Sydney‘s Yellow Eyes RANKIN RANKIN RANKIN RANKIN Hundreds & Thousands Death Spikes Epitaph II RANKIN RANKIN Kate‘s Look, Kate Moss Sparkling Death Masks SANTE ANDREAS H. -

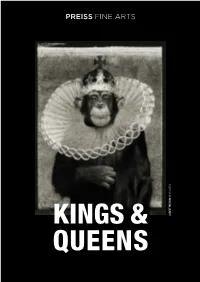

Kings & Albert Watson, King Casey Ii

KING CASEY II KINGS & ALBERT WATSON, QUEENS KINGS & ALISON JACKSON MICHEL COMTE QUEENS Preiss Fine Arts presents with the exhibition „Kings & Queens“ glamorous masterpieces of fi ne art photography by the most famous photographers of our time. The viewer is fascinated by majestic and beautiful artworks such as Albert Watson’s humorous and famous portrait of „King Casey - a monkey as king“, Ellen von Unwerth’s Jennifer Lopez as Queen of Pop and glittering wonder, or Rankin’s „Queen of Supermodels“ Kate Moss. Whether prominent personalities, imposing animals, royal staging or beautiful, strong women as queens - to admire is a unique collection of works of fi ne art photography. Various artistic styles open up the scope for interpretation and the idea of beauty. SYLVIE BLUM RANKIN All artworks are available at Preiss Fine Arts, Each artwork is done and signed by the artist and part of a strictly limited edition. ELLEN VON UNWERTH TERRY 0’NEILL ALISON JACKSON ALISON JACKSON ALISON JACKSON Mick Jagger, Ironing Diana, Finger Up ALISON JACKSON ALISON JACKSON Queen In bed with Corgis Queen on Loo RANKIN RANKIN RANKIN Touch your Toes Hundreds & Thousands RANKIN RANKIN Kate Moss, Back Sparkling Death Masks ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH Meow, Jessica Chastain Bedazzled, Lindsay Wixson ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH Freshly Bloomed Jennifer Lopez Rihanna ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH Naomi Campbell Diane Kruger ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH ELLEN VON UNWERTH Claudia Schiffer, -

TERESE PAGH at the Age of 12 Terese Was Scouted by Elite

TERESE PAGH At the age of 12 Terese was scouted by Elite Copenhagen director Trice Tomsen and her first professional shoot was photographed by Danish supermodel Helena Christensen for Harper's Bazaar. Her international career began when she won the Danish Elite Model Look competition 2006 at the age of 14 and placed second in the international finale in 2007, following in the footsteps of former contestants Claudia Schiffer, Naomi Campbell, Gisele Bündchen and Lara Stone. Terese has walked the runway for Cacharel, Collette Dinnigan & Danish designers Stine Goya, Munthe Plus Simonsen and Ivan Grundahl. Terese finished her schooling in early 2011 and is now living in New York City doing bookings for Marilyn Model Agency, works in Denmark through her mother agency Elite Model Management Copenhagen and worldwide through associated agencies. Recent campaigns include Express clothing SS 2011, which featured her prominently in its advertising, Victoria's Secret catalog & video work, a magazine editorial & gallery show for Tush Magazine by Ellen von Unwerth and a shoot with Terry Richardson for V Magazine. She is the 2011 face of New York designer Kevork Kiledjian Resort 2012 and Spanish designer Sonia Peña and has featured videos on their websites. Magazine cover credits in 2011 include Elle Oriental, July; Grazia Italy issues May, June & July; Italian magazine IO Donna, September; and Swedish magazine Damernas Värld, December. Other cover credits include Scandinavian magazines Sirene & the Mode - Femmes issue; and Dutch fashion magazine Jackie - The Bachelor 50 List cover story. Fashion/Art videos: Backstage Egò Sposa 2010 & 2011; Sonia Peña 2011; Stine Goya SS 11 - Make- up; Making of BDBA SS 11; Redskins Sportwear Backstage SS 11 & FW 11; Express Sept. -

Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children / Sarah Grogan

Body Image Body Image reviews current research on body image in men, women and children and presents fresh data from Britain and the United States. Sarah Grogan brings together perspectives from psychology, sociology, women’s studies and media studies to assess what we know about the social construction of body image at the end of the twentieth century. Most previous work on body image concentrates on women. With the male body becoming more ‘visible’ in popular culture, researchers in psychology and sociology have recently become more interested in men’s body image. Sarah Grogan presents original data from interviews with men, women and children to complement existing research, and provides a comprehensive investigation of cultural influences on body image. Body Image will be of interest to students of psychology, sociology, women’s studies, men’s studies, media studies, and anyone with an interest in body image. Sarah Grogan is Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Manchester Metropolitan University. Body Image Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children Sarah Grogan London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2001. © 1999 Sarah Grogan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Lisa Jachno Manicurist

Lisa Jachno Manicurist Celebrities Adriana Lima Bella Thorn Elisha Cuthbert Helen Hunt Aisha Tyler Carmen Electra Elizabeth Banks Holly Hunter Alec Baldwin Carmen Kass Elizabeth Hurley Isabel Lucas Alessandra Ambrosio Carolyn Murphy Elizabeth Perkins Isabeli Fontana Alicia Silverstone Carrie-Anne Moss Elizabeth Shue J.C. Chavez Alicia Witt Carrie Underwood Elle MacPherson Jacqueline Smith Alyssa Milano Cate Blanchett Ellen Degeneres Jada Pinkett Amanda Seyfried Catherine Zeta Jones Ellen Barkin Jaime Pressly Amber Valletta Celine Dion Elle Fanning Jamie Lee Curtis America Ferrera Charlize Theron Emma Stone Jane Seymour Amy Adams Cher Emma Roberts Janet Jackson Anastasia Cheryl Tiegs Emmy Rossum January Jones Andie MacDowell Christina Aguilera Erika Christensen Jason Shaw Angelina Jolie Christina Applegate Estella Warren Jenna Fischer Angie Harmon Christina Ricci Eva Longoria Jeanne Tripplehorn Anjelica Huston Christy Turlington Evan Rachel Wood Jennifer Aniston Anna Kendrick Chole Moretz Faith Hill Jennifer Garner Anne Hathaway Ciara Farrah Fawcett Jennifer Lopez Annette Bening Cindy Crawford Fergie Jennifer Love Hewett Ashley Greene Claire Danes Fiona Apple Jennifer Hudson Ashley Judd Claudia Schiffer Fran Drescher Jennifer Tilly Ashley Tisdale Courteney Cox Gabrielle Union Jeremy Northam Ashlee Simpson Courtney Love Garcelle Beauvais Jeri Ryan Audrina Patridge Caroline Kennedy Gemma Ward Jessica Alba Avril Lavigne Daisy Fuentes Gerri Halliwell Jessica Biel Baby Face Daria Werbowy George Clooney Jessica Simpson Bette Midler Daryl Hannah -

Helena's Danish Delights

FOR THE MODERN TRAVELER FROM SCANDINAVIAN AIRLINES | AUGUST 2017 8 8 FOR THE MODERN TRAVELER FROM SCANDINAVIAN AIRLINES Fully | focused AUGUST 2017 Helena Christensen reflects on life behind and in front of the camera SLOWLY DOES IT Munich a new way | BEAUTIFUL BERGEN Norway’s architectural heritage ELISABETH MOSS Tales to tell | NEW YORK In the swing SOMMARØY A different kind of paradise | TORSTEN JANSSON Heart of glass CLASSIC CARS Blast from the past | EILAT From camels to sharks XxxxMeet HELENAXXXXXXXXXX CHRISTENSEN GLOBAL CITIZEN Part of the global modeling royalty, Helena Christensen somehow manages to keep out of the spotlight on the streets of New York and reveals that despite her hectic career, there’s nothing she loves more than being on the go. By Sam Eichblatt Photos by Christy Bush 58 SCANDINAVIANTRAVELER.COM AUGUST 2017 Xxxx XXXXXXXXXX AUGUST 2017 SCANDINAVIANTRAVELER.COM 59 Meet HELENA CHRISTENSEN ‘My first When I refer to her cohort of super- travel models – memorably dubbed The Magnif- cent Seven by the New York Times in 1996 – as “iconic,” she all but rolls her eyes and memories says dryly, “Well, we got lucky – I think that’s more the word.” are mostly The model, photographer and co- founder of NYLON magazine has had here are few cities in the world where a many diferent roles during her career, but about woman with a face as recognizable as Hel- through out her life, travel has been a con- ena Christensen’s can stroll up the side- stant. waiting on walk and slip into a busy café in the mid- She starts by telling me that her mother Tdle of the afternoon without attracting any worked in the fnancial department of SAS standby’ attention. -

Helena Christensen FIFTY& Fabulous

INTERVIEW Helena Christensen FIFTY& fabulous Supermodel - Fotograaf - VN-ambassadeur Ze werd eind vorig jaar vijftig en is nog even mooi als in haar gloriedagen. Maar anno 2019 wil topmodel Helena Christensen haar beauty vooral van binnenuit laten komen en zet ze zich in als ambassadeur van VN-vluchtelingenorganisatie UNHCR. Met Elegance deelt ze het persoonlijke verhaal over haar bezoek aan een kamp in Rwanda. TEKST JILL WAAS FOTOGRAFIE HECTOR PEREZ E L E G A N C E 2019 | 109 INTERVIEW Helena bezocht Rwanda Helena Christensen (25 december in oktober 1968) maakte in de jaren 90 furore 2018. als een van de grootste topmodellen. Samen met Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, Elle Macpherson en Claudia Schiffer vormde ze The Magnificent Seven. Alleen al bij het noemen van hun voornamen, wist de hele wereld wie deze dames waren. Ze domineerden de runways. Helena speelde de hoofdrol in de inmiddels legendarische Wicked game- video van Chris Isaak. Ze stond op cover van grote bladen als Vogue, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar en W. En ze deed campagnes voor grote modemerken zoals Chanel, Versace, Lanvin, Prada, Sonia Rykiel, Hermès en Valentino. Bovendien was ze een van de eerste Helena over Alina’s verhaal: Angels van lingeriemerk Victoria’s ‘Toen het conflict letterlijk Alina’s leven binnenviel, greep ze Secret. haar kinderen en vluchtte. Ze rende weg van haar thuis, haar dorp, haar geliefde land Burundi. In de chaos van het vluchten werd ze gescheiden van haar man. Ze heeft hem sindsdien niet Ik heb de lijn van mannen, vrouwen en kinderen zó duidelijk meer gezien.’ op mijn netvlies staan. -

Next34 October11

NEXT 34_OCTOBER 11 David Favrod, de la série Le Tremblement du temps, 2011 NEXT 34_OCTOBER 11_P3 SOMMAIRE / CONTENTS Yann Mingard, de la série The Yellow Leaves, Tuva, Sibérie, 2003-2009 NEAR • association suisse pour la photographie contemporaine • avenue vinet 5 • 1004 lausanne • www.near.li • [email protected] NEXT 34_OCTOBER 11_P4 SOMMAIRE / CONTENTS Thomas Rousset, de la série Prabérians, 2009 RUBRIQUES / SECTIONS NEAR P13 EVENEMENTS / EVENTS P17 EXPOSITIONS / EXHIBITIONS P45 FESTIVALS P191 PUBLICATIONS P223 PRIX / AWARDS P243 FORMATION / EDUCATION P255 NEXT − WEBZINE NEXT est le webzine mensuel édité par l'association NEAR qui vous offre une vision d'ensemble de l'actualité de la photographie contemporaine en Suisse et ailleurs : événements, expositions, publications, festivals et prix internationaux, formation… Vous y trouvez également des informations sur les activités de NEAR et sur ses membres, notamment dans les portfolios et les interviews. Edited by NEAR − swiss association for contemporary photography − NEXT is a monthly webzine of news concerning mainly contemporary photography in Switzerland and elsewhere : events, exhibitions, publications, international festivals and awards, education... You will also find information about activities organized by NEAR and about its members in the portfolios and interviews. Tous les numéros / All issues : http://www.near.li/html/next.html Maquette / Graphic design : Ilaria Albisetti, www.latitude66.net Rédactrice en chef / Chief editor : Nassim Daghighian, présidente de NEAR ; [email protected] -

1019 IV Silent Forces.Indd

in NAMRATA SHIRODKAR Entrepreneur and fi lm producer Before Namrata Shirodkar took on the responsibil- ity of running her megastar husband Mahesh Ba- bu’s production house, she was Femina Miss India B(1993) and acted in fi lms like Bride And Prejudice (2004) and Pukar (2003). “I handle various depart- ments, like Mahesh’s endorsements, marketing, costumes, graphics and putting teams in place. My day starts at my home offi ce, where I bridge the gap between all these different aspects and put projects together,” she says. Shirodkar and her husband are actively involved with the NGO Grammam (The Village) Foundation that works on the upliftment of two villages, Siddhapuram and Burripalem, in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Shirodkar also has two young children and, like most young mothers, has had to evolve her look over the years. “Over- dressing feels like a chore to me. I pay a lot of atten- tion to clean cuts and lines. I know people say this often, but I do like the classics—white shirts and denims—that I can repeat without stressing.” STYLE INFLUENCES: “Growing up, I loved Christy Turlington’s casual approach to dressing. I loved that laidback, ’90s vibe. These supermodels were on the biggest magazine covers but there was something so carefree about them. I would even add Helena Christensen, Tyra Banks, Cindy Craw- ford and Naomi Campbell to that list.” WARDROBE ESSENTIALS: “Wide-leg trou- sers are a big part of my wardrobe. Max Mara has the most fl attering cuts. I love a crisp white shirt— Dior does great ones. -

The Annual Report on the World's Most Valuable Retail Brands February 2015

Retail 50 2015The annual report on the world’s most valuable retail brands February 2015 Foreword. David Haigh, CEO, Brand Finance “The boardroom can sometimes feel like the tower of Babel, with CMOs and CFOs speaking mutually unintelligible languages, damaging the prospects for what should be their shared goals. Brand Finance bridges the gap between marketing and finance.” What is the purpose of a strong brand; to communicate the value of their work and boards and accounting. We understand the importance of Omaha certainly does extremely well from attract customers, to build loyalty, to motivate then underestimate the significance of their of design, advertising and marketing, but we most of his investments, but could he be doing staff? All true, but for a commercial brand at brands to the business. also believe that the ultimate and overriding better? least, the first answer must always be ‘to purpose of brands is to make money. make money’. Sceptical finance teams, unconvinced by what It is all well and good to want a strong brand that they perceive as marketing mumbo jumbo may That is why we connect brands to the bottom customers connect with, but as with any asset, Huge investments are made in the design, fail to agree necessary investments. What line. By valuing brands we provide a mutually without knowing the precise, financial value, how launch and ongoing promotion of brands. Given marketing spend there is can end up poorly intelligible language for marketers and finance can you know if you are maximising your their potential financial value, this makes sense. -

P24-25 Layout 1

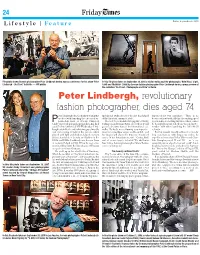

24 Friday Lifestyle | Feature Friday, September 6, 2019 File photo shows German photographer Peter Lindbergh during a press conference for his show ‘Peter In this file photo taken on September 24, 2010 a visitor walks past the photographs ‘Kate Moss’ (right, Lindbergh - On Street’ in Berlin. — AFP photos 1994) and ‘Mathilde’ (1989) by German fashion photographer Peter Lindbergh during a press preview of the exhibition ‘On Street - Photographs and Film’ in Berlin. eter Lindbergh, the German photographer up, big-hair studio shoots of the day-that helped imperfections was legendary. “There is no credited with launching the careers of su- define his stark, cinematic style. beauty without truth. All this fake making up of Ppermodels such as Naomi Campbell, The new faces included Evangelista, Christy a person into something that is not them cannot Cindy Crawford and Linda Evangelista, has died Turlington and Tatjana Patitz, all of whom would be beautiful. It is just ridiculous,” he said in No- aged 74, his family told AFP Wednesday. Lind- go on to become stars of the international cat- vember 2016 when launching the 2017 Pirelli bergh’s stark black-and-white images of models walks. “He had a way of turning your imperfec- calendar. and stars staring straight at the camera, which tions into something unique and beautiful... and For that feminist-friendly edition of a calendar played with light and shadow, helped overturn his images will always be timeless,” Crawford long synonymous with langorous nudes, he glossy standards of beauty and fashion in the wrote on her Instagram account. “Caring, kind, roped in veteran stars Helen Mirren and Char- 1980s and 1990s.