Wolverine ESA Proposed Rule Comments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo-Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report – Discussion Draft 2 1

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo- Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report DISCUSSION DRAFT (Quantified Model Data Subject to Refinement) Table of Contents 1. Project Background: ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Early Study Efforts and Initial Findings: ................................................................................................ 5 3. Background Data Collection Interviews: ................................................................................................ 6 4. Fixed-Facility Capital Cost Estimate Range Based on Existing Studies: ............................................... 7 5. Selection of Single Route for Refined Analysis and Potential “Proxy” for Other Routes: ................ 9 6. Legal Opinion on Relevant Amtrak Enabling Legislation: ................................................................... 10 7. Sample “Timetable-Format” Schedules of Four Frequency New York-Chicago Service: .............. 12 8. Order-of-Magnitude Capital Cost Estimates for Platform-Related Improvements: ............................ 14 9. Ballpark Station-by-Station Ridership Estimates: ................................................................................... 16 10. Scoping-Level Four Frequency Operating Cost and Revenue Model: .................................................. 18 11. Study Findings and Conclusions: ......................................................................................................... -

20210419 Amtrak Metrics Reporting

NATIONAL RAILROAD PASSENGER CORPORATION 30th Street Station Philadelphia, PA 19104 April 12, 2021 Mr. Michael Lestingi Director, Office of Policy and Planning Federal Railroad Administrator U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 Dear Mr. Lestingi: In accordance with the Metrics and Minimum Standards for Intercity Passenger Rail Service final rule published on November 16, 2020 (the “Final Rule”), this letter serves as Amtrak’s report to the Federal Railroad Administration that, as of April 10, 2021, Amtrak has provided the 29 host railroads over which Amtrak currently operates (listed in Appendix A) with ridership data for the prior month consistent with the Final Rule. The following data was provided to each host railroad: . the total number of passengers, by train and by day; . the station-specific number of detraining passengers, reported by host railroad whose railroad right-of-way serves the station, by train, and by day; and . the station-specific number of on-time passengers reported by host railroad whose railroad right- of-way serves the station, by train, and by day. Please let me know if you have any questions. Sincerely, Jim Blair Sr. Director, Host Railroads Amtrak cc: Dennis Newman Amtrak Jason Maga Amtrak Christopher Zappi Amtrak Yoel Weiss Amtrak Kristin Ferriter Federal Railroad Administration Mr. Michael Lestingi April 12, 2021 Page 2 Appendix A Host Railroads Provided with Amtrak Ridership Data Host Railroad1 Belt Railway Company of Chicago BNSF Railway Buckingham Branch Railroad -

1.0 Purpose and Need of the Proposed Action

1.0 Purpose and Need of the Proposed Action 1.1 Description of the Proposed Action The City of Ann Arbor, Michigan in partnership with the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) and the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) have proposed to construct an intermodal station within the City of Ann Arbor. This project would support the existing Amtrak intercity service between Detroit, Michigan and Chicago, Illinois, the planned Midwest High Speed Rail service between Detroit/Pontiac and Chicago and the future proposed regional commuter rail service (see Section 1.6, Relationship to other Transportation Planning Initiatives). This Environmental Assessment will include an evaluation of the existing station location along with other alternatives in Ann Arbor, and will assess their ability to support current and future Intercity Passenger rail service, in addition to local and regional transit, pedestrian and bicycle transportation. 1.2 Project Study Area Exhibit 1.1: Project Study Area Source: ESRI The project study area is located in the City of Ann Arbor, Michigan, along the rail line used by the Wolverine Intercity Passenger rail service, (see Exhibit 1.1) from where the City boundary on the northwest meets the rail line, southwest through the city to the city limits at the intersection of US Highway 23 and the rail line. The project study area for the proposed intermodal station is completely within the city limits of Ann Arbor as the City of Ann 1 Arbor will assume ownership of a new station. The existing station is located at 325 Depot Street, northwest of the central Ann Arbor downtown area, the University of Michigan (U-M) central campus and the U-M Medical Center. -

Presentation

People Before Freight On-time trains on host railroads 3 LATEST REPORT CARD SIGNALS NEW GOLDEN AGE OF ON-TIME TRAINS 1 Canadian Pacific A 2 BNSF A 3 Union Pacific A 4 CSX A 5 Canadian National A 6 Norfolk Southern A Average grade for all host railroads: A 4 Amtrak National Network Passengers Continue to Experience Poor On-Time Performance 1 Canadian Pacific A 2 BNSF B 3 Union Pacific B- 4 CSX B- 5 Canadian National D- 6 Norfolk Southern F Average grade for all host railroads: C 5 Grading National Network routes on OTP 17 of 28 State-Supported Services Fail Class I Freight Percentage of trains on‐time State‐Supported Trains Route Host Railroads within 15 minutes Pass = 80% on‐time Hiawatha CP 96% Keystone (other hosts) 91% Capitol Corridor UP 89% New York ‐ Albany (other hosts) 89% Carl Sandburg / Illinois Zephyr BNSF 88% Ethan Allen Express CP 87% PASS Pere Marquette CSX, NS 84% Missouri River Runner UP 83% Springfield Shuttles (other hosts) 82% Downeaster (other hosts) 81% Hoosier State CSX 80% Pacific Surfliner BNSF, UP 78% Lincoln Service CN, UP 76% Blue Water NS, CN 75% Roanoke NS 75% Piedmont NS 74% Richmond / Newport News / Norfolk CSX, NS 74% San Joaquins BNSF, UP 73% Pennsylvanian NS 71% Adirondack CN, CP 70% FAIL New York ‐ Niagara Falls CSX 70% Vermonter (other hosts) 67% Cascades BNSF, UP 64% Maple Leaf CSX 64% Wolverine NS, CN 60% Heartland Flyer BNSF 58% Carolinian CSX, NS 51% Illini / Saluki CN 37% 6 Grading National Network routes on OTP 14 of 15 Long Distance Services Fail Class I Freight Percentage of trains on‐time Long -

Recreation Master Plan

THE VILLAGE OF WOLVERINE LAKE RECREATION MASTER PLAN 2016 - 2020 Tiki Night on Wolverine Lake Adopted February 10, 2016 THE VILLAGE OF WOLVERINE LAKE RECREATION MASTER PLAN 2016 – 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V ILLAGE C OUNCIL John Magee, President Ed Sienkiewicz, President Pro-Tem Mark Duff Patrick Nagy Brian Nedrow John Scott Mike Stack P ARK AND R ECREATION B OARD Lynn Lewis, Chairperson Diane Braykovich Mark Duff, Council Liaison Scott Fredericks, Planning Liaison Jack Hansel Sig Jamison Amber Pisha V ILLAGE S TAFF Sharon Miller, Administrator & Clerk Michael Kondek, Treasurer John Ellsworth, Police Captain Tim Brandt, Building Inspector S PECIAL T HANKS Tom Hite - Photos V ILLAGE OF W OLVERINE L AKE R ECREATION M ASTER P LAN i T ABLE OF C ONTENTS Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Community Description ....................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Structure ....................................................................................................................................20 Recreation Inventory ...........................................................................................................................................22 Public Participation .............................................................................................................................................49 -

Comparing Amtrak and Motorcoach Service

Supporting Passenger Mobility and Choice by Breaking Modal Stovepipes Comparing Amtrak and Motorcoach Service July 2013 M.J. Bradley & Associates LLC (603) 647 5746 / www.mjbradley.com Authors: Dana Lowell and David Seamonds M.J. Bradley & Associates LLC 1000 Elm Street, 2nd Floor Manchester, NH 03101 (603) 647-5746 x103 [email protected] This document was prepared by M.J. Bradley & Associates for submission to: 111 K Street, NE 9th Floor Washington, DC 20002-8110 The Reason Foundation 5737 Mesmer Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90230 651 Pennsylvania Ave, SE Washington, DC 20003 Comparison of Amtrak Trips to Motorcoach Trips Table of Contents Key Findings .................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 1 Study Methodology .............................................................................................. 11 1.1 Current Amtrak Service ..................................................................................... 11 1.2 Current Motorcoach Service .............................................................................. 12 1.3 Incremental Trip Time ....................................................................................... 14 1.4 Value of Incremental Trip Time......................................................................... 16 1.5 Emissions .......................................................................................................... -

TRAINS. MORE CITIES. Better Service

MORE TRAINS. MORE CITIES. Better Service. Amtrak’s Vision for Improving Transportation Across America | June 2021 National Railroad Passenger Corporation 1 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington, DC 20001 Amtrak.com 01 Executive Summary 4 02 Introduction 8 03 The Challenges Expansion Will Address 13 04 The Solution Is Passenger Rail 20 05 The Right Conditions For Expansion 24 06 Analysis For Supporting Service Expansion 33 07 Implementation 70 08 Conclusion 73 Appendix Amtrak Route Identification Methodology 74 01 Executive Summary OVERVIEW As Amtrak celebrates 50 years of service to America, we are focused on the future and are pleased to present this comprehensive plan to develop and expand our nation’s transportation infrastructure, enhance mobility, drive economic growth and meaningfully contribute to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. With our seventeen state partners we provide service to forty-six states, linking urban and rural areas from coast to coast. But there is so much more to be done, from providing transportation choices in more locations to reducing highway and air traffic congestion to addressing longstanding economic and social inequities. This report describes how. To achieve this vision, Amtrak proposes that the federal government invest $75 billion over fifteen years to develop and expand intercity passenger rail corridors around the nation in collaboration with our existing and new state partners. Key elements of Amtrak’s proposal include: Sustained and Flexible Funding Paths Federal Investment Leadership Amtrak proposes a combination of funding mechanisms, including Following the successful models used to develop the nation’s direct federal funding to Amtrak for corridor development and Interstate Highway System and our aviation infrastructure, Amtrak operation, and discretionary grants available to states, Amtrak proposes significant Federal financial leadership to drive the and others for corridor development. -

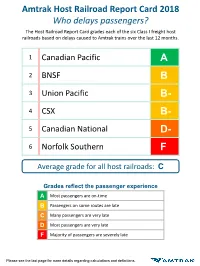

Amtrak Host Railroad Report Card 2018 Who Delays Passengers?

Amtrak Host Railroad Report Card 2018 Who delays passengers? The Host Railroad Report Card grades each of the six Class I freight host railroads based on delays caused to Amtrak trains over the last 12 months. 1 Canadian Pacific A 2 BNSF B 3 Union Pacific B- 4 CSX B- 5 Canadian National D- 6 Norfolk Southern F Average grade for all host railroads: C Grades reflect the passenger experience A Most passengers are on-time B Passengers on some routes are late C Many passengers are very late D Most passengers are very late F Majority of passengers are severely late Please see the last page for more details regarding calculations and definitions. Amtrak Route Grades 2018 How often are trains on-time at each station within 15 minutes of schedule? Class I Freight Percentage of trains on-time State-Supported Trains Route Host Railroads within 15 minutes Pass = 80% on-time Hiawatha CP 96% Keystone (other hosts) 91% 17 of 28 routes fail to Capitol Corridor UP 89% achieve 80% standard New York - Albany (other hosts) 89% Carl Sandburg / Illinois Zephyr BNSF 88% Ethan Allen Express CP 87% Pere Marquette CSX, NS 84% PASS Missouri River Runner UP 83% Springfield Shuttles (other hosts) 82% Downeaster (other hosts) 81% Hoosier State CSX 80% Pacific Surfliner BNSF, UP 78% Lincoln Service CN, UP 76% Blue Water NS, CN 75% Roanoke NS 75% Piedmont NS 74% Richmond / Newport News / Norfolk CSX, NS 74% San Joaquins BNSF, UP 73% Pennsylvanian NS 71% Adirondack CN, CP 70% New York - Niagara Falls CSX 70% FAIL Vermonter (other hosts) 67% Cascades BNSF, UP 64% Maple -

Amtrak General and Legislative Annual Report & FY2022 Grant Request

April , The Honorable Kamala Harris President of the Senate U.S. Capitol Washington, DC The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House of Representatives U.S. Capitol Washington, DC Dear Madam President and Madam Speaker: I am pleased to transmit Amtrak’s Fiscal Year (FY) General and Legislative Annual Report to Congress, which includes our FY grant request, legislative proposals, and a summary of the various actions taken by Amtrak to respond to the Coronavirus pandemic. To overcome the setbacks to service and financial performance we faced during this crisis, we seek Congress’s continued strong support in FY so that we can return to the successes and growth we accomplished in FY . Amtrak is poised to be a key part of the nation’s post-pandemic recovery and low-carbon transportation future, but to do so we require continued Federal government support, including robust investment. Despite the difficulties of the past year, Amtrak was able to achieve significant accomplishments and continue progressing vital initiatives, such as: . Safety: Completed Positive Train Control (PTC) installation and operation everywhere it was required across entire network and advanced our industry-leading Safety Management System (SMS). Moynihan Train Hall: Amtrak, in partnership with New York State and the Long Island Rail Road, opened the first modern, large-scale intercity train station built in the U.S. in over years. FY Capital Investment: Performed $. billion in infrastructure and fleet work. FY Ridership: Provided . million customer trips, which, while a decrease of . million passengers from FY owing to the pandemic-related travel reductions; reflects record performance during the five months preceding the onset of the Coronavirus. -

SPEEDLINES, High-Speed Intercity Passenger Rail Committee, Issue

High-Speed Intercity Passenger Rail SPEEDLINES May 2021 ISSUE #31 WASHINGTON WIRE: Legislative Update » p. 7 AMTRAK’S VISION TO GROW » p. 10 HIGH-SPEED AND INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL PROGRESS » p. 21 CONTENTS 2 SPEEDLINES MAGAZINE On the front cover: OVER THE NEXT 15 YEARS, AMTRAK’S VISION FOR 3 CHAIRMAN’S LETTER EXPANSION IS TO CONNECT UP TO 160 COMMUNI- Greetings from our Chair, Joe Giulietti TIES THROUGHOUT THE UNITED STATES BY BUILD- ING NEW OR IMPROVED RAIL CORRIDORS IN MORE THAN 25 STATES. AS PART OF THIS PLAN, AMTRAK WILL INTRODUCE NEW STATIONS IN OVER HALF THE 4 APTA’S EVENT CALENDAR U.S. STATES, INCREASE RAIL SERVICE TO 47 OF THE TOP FEATURE ARTICLE: 50 METROPOLITAN AREAS AND CREATE OVER HALF A MILLION NEW, WELL-PAYING JOBS. 5 CAHSR RECOVERY & TRANSFORMATION 7 WASHINGTON WIRE 9 STB NOMINATION NEWS 10 AMTRAK’S VISION TO GROW 12 SPOTLIGHT ABOVE: Biden joined Amtrak executives for a 13 REGULATORY REFORM ceremony in Philadelphia, PA USA to pay homage to the past and share Amtrak’s vision for the future. 16 REVISED PLAN: APPLE VALLEY PROJECT CHAIR: JOE GIULIETTI VICE CHAIR: CHRIS BRADY 18 REVIVING A RAIL RESOLUTION SECRETARY: MELANIE K. JOHNSON OFFICER AT LARGE: MICHAEL MCLAUGHLIN IMMEDIATE PAST CHAIR: AL ENGEL 21 STATE ROUNDUP - 2021 PROGRESS EDITOR: WENDY WENNER PUBLISHER: ERIC PETERSON ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER: DAVID WILCOCK IMMEDIATE PAST PUBLISHER: KENNETH SISLAK PUBLISHER EMERITUS: AL ENGEL © 2011-2021 APTA - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SPEEDLINES is published in cooperation with: AMERICAN PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION ASSOCIATION 1300 I Street NW, Suite 1200 East Washington, DC 20005 3 A letter from our Chair: Joseph Giulietti This is an exciting time to be involved in public transportation and especially the high-speed and intercity passenger rail business. -

AMTRAK 2013: NEW YEAR BRINGS MAJOR PROJECTS Infrastructure Upgrades, New Equipment Milestones and High-Speed Rail Advancements Lead Full Agenda

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ATK-13-008 January 10, 2013 Contact: Media Relations 202 906.3860 AMTRAK 2013: NEW YEAR BRINGS MAJOR PROJECTS Infrastructure upgrades, new equipment milestones and high-speed rail advancements lead full agenda WASHINGTON – Amtrak enters 2013 with a full and robust agenda of infrastructure upgrade projects, significant milestones for new equipment orders and key actions to advance its Northeast Corridor (NEC) high-speed rail program. Among the projects include completion of the NEC Niantic River Movable Bridge replacement project, delivery of the first units of new equipment orders for 70 electric locomotives and 130 single-level long-distance passenger cars, expansion of Acela Express high- speed service with an additional New York – Washington round-trip and initiation of the process to acquire next-generation high-speed train sets. “Amtrak continues to advance and invest in projects that provide both near-term benefits and long-term improvements for the effective delivery and reliability of intercity passenger rail service,” said President and CEO Joe Boardman. During the coming year, three Amtrak-owned or maintained corridors will be under various stages of construction to enhance and ultimately increase rail capacity including the Springfield Line in Conn., the Hudson Line in upstate N.Y. and a section of the NEC in N.J. In addition, Amtrak anticipates reaching agreement in 2013 with the Michigan Department of Transportation to operate, dispatch and maintain a section of state-owned railroad from Kalamazoo to -

SPEEDLINES, High-Speed Intercity Passenger Rail Committee, June 2018

High-Speed Intercity Passenger SPEEDLINES JUNE 2018 ISSUE #23 The New Haven-Springfield CTrail service will cost more than $760 million in construction: $564.3 million from the state of Connecticut and $204.8 million from the federal government. 2 CONTENTS SPEEDLINES MAGAZINE 3 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Your voice is much-needed as we strive toward an innovative, modern, passenger-focused railway network. It takes understanding the issues and concerns that you face every day and I hope that the upcoming Rail Conference in Denver can provide the venue for that to take place. 4 APTA RAIL CONFERENCE 5 STATE PROJECTS ROUND-UP » p. 21 17 FEDERAL FUNDING OPPORTUNITIES On the front cover: Officials have announced a mid-June start date 20 UPDATES ON CONNECTICUT for new high-frequency, high-speed rail service between New Haven, Connecticut and Springfield, Massachusetts. The new service called CTrail will 24 CALIFORNIA HSR have 17 train trips a day between New Haven and Hartford with a dozen connecting to Springfield 26 PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP (P3) beginning June 18th. The trains will travel at top speeds of 110 mph. Connecticut Gov. Dannell Malloy encouraged spending hundreds of millions of dollars 28 FRA / AMTRAK SPOTLIGHT to build the high-speed rail infrastructure as a way to spur economic development along the new line. 32 BRIGHTLINE CHAIR: ANNA BARRY VICE CHAIR: AL ENGEL 34 THE HISTORY OF HSR SECRETARY: JENNIFER BERGENER OFFICER AT LARGE: DAVID CAMERON IMMEDIATE PAST CHAIR: PETER GERTLER 35 APTA’S 4TH ANNUAL POLICY FORUM EDITOR: WENDY WENNER PUBLISHER: AL ENGEL 44 LEGISLATIVE REPORT ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER: KENNETH SISLAK ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER: ERIC PETERSON LAYOUT DESIGNER: WENDY WENNER © 2011-2018 APTA - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SPEEDLINES is published in cooperation with: AMERICAN PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION ASSOCIATION 1300 I Street NW, Suite 1200 East Washington, DC 20005 SPEEDLINES | June 2018 3 Dear HS&IPR Committee & Friends: Welcome to our Spring 2018 issue of Speedlines.