Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Refugee Book Reading Campaign 2019 - Adult Booklist

Refugee Book Reading Campaign 2019 - Adult Booklist Read a Book About Refugees There is a great variety of books written about refugees - including award-winning fiction – and books by refugees themselves. Why not borrow one of these from your local library or buy one from your local book shop? Do you have a book club? Maybe you would consider adding one of these titles to the reading list. Fiction Sea Prayer Author: Khaled Hosseini, Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, London A heart-wrenching story about a refugee family from the international bestselling author of The Kite Runner. “A truly gifted teller of tales … he's not afraid to pull every string in your heart to make it sing” – The Times Deep Sea Author: Annika Thor, Publisher: Delacorte Press. Readers of Anne of Green Gables and Hattie Ever After will love following Stephie’s story, which takes place during World War II and began with A Faraway Island and continued with The Lily Pond. Three years ago, Stephie and her younger sister, Nellie, escaped the Nazis in Vienna and fled to an island in Sweden, where they were taken in by different families. Now sixteen-year-old Stephie is going to school on the mainland. Stephie enjoys her studies, and rooming with her school friend, May. But life is only getting more complicated as she gets older. Stephie might lose the grant money that is funding her education. Her old friend Verra is growing up too fast. And back on the island, Nellie wants to be adopted by her foster family. Stephie, on the other hand, can’t stop thinking about her parents, who are in a Nazi camp in Austria. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION ....................................................... -

Judy: a Dog in a Million Pdf, Epub, Ebook

JUDY: A DOG IN A MILLION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Damien Lewis | 10 pages | 01 Jan 2015 | W F Howes Ltd | 9781471284243 | English | Rearsby, United Kingdom Judy: A Dog in a Million PDF Book Youth Field Trial Alliance. Judy fell pregnant, and gave birth to thirteen puppies. When he boarded the ship, Judy climbed into a sack and Williams slung it over his shoulder to take on board. We empower all our people, by respecting and valuing what makes them different. Judy, the heroine dog in a million. The guards had grown tired of the dog and sentenced her to death. Schools PDSA. Judy had won hers for her many life-saving acts aboard the Royal Navy gunboats and in the POW camps, and for the role she played everywhere by boosting morale. If you only read one book in your life read this book. Year published He realised as he looked back that she had been pulling him away from a Leopard. Sign In. Goldstone-Books via United Kingdom. Judy with her handler Frank Williams. Author Damien Lewis. Archived from the original on 9 November The Books Podcast. She kept man and mind together in the darkest days, with her love and her loyalty. Afterwards they contacted the Panay and offered them the bell back in return for Judy. Role Finder Start your Royal Navy journey by finding your perfect role. Joining Everything you need to know about joining the Royal Navy, in one place. In stock. He has written a dozen non-fiction and fiction books, topping bestseller lists worldwide, and is published in some thirty languages. -

Human Security in Sudan: the Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission

Human Security in Sudan: The Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission Prepared for the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ottawa, January 2000 Disclaimer: This report was prepared by Mr. John Harker for the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. The views and opinions contained in this report are not necessarily those of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. 1 Human Security in Sudan: Executive Summary 1 Introduction On October 26, 1999, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lloyd Axworthy and the Minister for International Co-operation, Maria Minna, announced several Canadian initiatives to bolster international efforts backing a negotiated settlement to the 43-year civil war in Sudan, including the announcement of an assessment mission to Sudan to examine allegations about human rights abuses, including the practice of slavery. There are few other parts of the world where human security is so lacking, and where the need for peace and security - precursors to sustainable development - is so pronounced. Canada's commitment to human security, particularly the protection of civilians in armed conflict, provides a clear basis for its involvement in Sudan and its support for the peace process. Charm Offensive, or Signs of Progress? Following the visit to Khartoum of an EU Mission, a political dialogue was launched by the European Union on November 11 1999. The EU was of the view that there has been sufficient progress in Sudan to warrant a renewed dialogue. In this view, there has been a positive change, and it is necessary to encourage the Sudanese, and push them further where there is need. -

The Terror Trade Times

The Terror Trade Times Amnesty International www.amnesty.org JUNE 2002 AI Index : ACT 31/001/2002 Issue No. 3 Page 1 (cont’d page 2) No arms for atrocities G8's uncontrolled trade in arms and military aid undermines fundamental human rights and sustainable development This issue of The Terror Trade Times, largely examines ways in which military and security exports from seven of the G8 countries - the USA, the Russian Federation, France, the United Kingdom (UK), Germany, Italy and Canada - are contributing to human rights abuses and undermining the prospects for social and economic development around the world. All states have a fundamental legal obligation to assess whether the arms and security equipment and training they transfer are likely to be used by the recipients to commit human rights abuses and to ensure that through such transfers they are not knowingly assisting in such abuses. Arms transfers are not lawful just because the recipients are government agents or the transfers have been authorized by government officials. They can only be lawful if they are made in accordance with international standards. The failure of governments to fulfil this obligation is contributing to the destruction of millions of lives, particularly in Africa. The consequences of irrespon-sible arms transfers are there for all to see. Yet governments, far from learning from their mistakes, seem set to make the problem even worse. The current US-led “war against terrorism” is being accompanied by massive transfers of military aid to those governments that have shown little regard for human rights protection. There has been no reduction in existing US military aid to countries such as Israel (US$2.04 billion), Egypt (US$1.3 billion), Jordan, Tunisia and Colombia. -

Sudan's Oilfields Burn Again

AFRICA Briefing Nairobi/Brussels, 10 February 2003 SUDAN’S OILFIELDS BURN AGAIN: BRINKMANSHIP ENDANGERS THE PEACE PROCESS I. OVERVIEW seeing it through to success in the next several months. In the first instance that means insisting on full implementation of the newly agreed Sudan’s peace process survived a major challenge in ceasefire provisions including an active role for the first weeks of the new year. Indeed, signature by the authorised verification team and the the parties of a strengthened cessation of hostilities withdrawal of troops to the positions they agreement on 4 February and a memorandum of occupied before the offensive. Holding the parties understanding codifying points of agreement on publicly accountable for violations will be key in outstanding issues of power and wealth sharing two ensuring their seriousness at the negotiating table. days later indicates that the momentum to end the twenty-year old conflict is strong. However, the The offensive from late December until the crisis produced by a government-sponsored beginning of February was an extension of the offensive in the Western Upper Nile oilfields at the government’s long-time strategy of depopulating oil- end of 2002 and through January raised questions rich areas through indiscriminate attacks on civilians about the Khartoum government’s commitment to in order to clear the way for further development of peace and showed that much more attention needs to infrastructure. Eyewitness accounts confirm that the be paid to pro-government southern militias and the tactics included the abduction of women and commercial and political agendas for which they are children, gang rapes, ground assaults supported by being used. -

Myanmar by Guven Witteveen

Southeast Asia in the Humanities and Social Science Curricula Sources for Understanding Myanmar By Guven Witteveen onsidering Myanmar’s mineral and people, courses for any grade level and all social events come alive again. John Falconer and Luca cultural wealth, it has not been easy to sciences gain from this set of sources. Invernizzi Tettoni’s Myanmar Style: Art, Archi- study nor common to discuss the many NonNative Writers in Print tecture, and Design of Burma (1998) is a visual Csocieties there. Access to information, stories, Starting with an early account, Helen G. Trager’s smorgasbord of material culture and craft tra- and lives in Myanmar has markedly improved Burma through Alien Eyes: Missionary Views of ditions, past and present. The 500 photos go since 2010, when the US rekindled ofcial and the Burmese in the Nineteenth Century was pub- beyond surfaces with chapters that explore the informal relations in Burma, as they refer to the lished in 1966 while the leaders of the coup d’etat presence of religion in daily life and work. Pico country. Entrepreneurs, tourists, and scholars reigned. The reader travels back through time to Iyer’s 1988 collection of essays, Video Night in also have engaged with people and organizations understand early colonial initiatives from Brit- Kathmandu, includes one relating to Myanmar, there more and more. One result has been the ain and the lives of those dedicating themselves “The raj is dead! Long live the raj!” Social change need for useful sources of current conditions, to engaging with the local people and languages and inroads of Western society are prominent in as well as ways to understand the cultural con- in Burma. -

My LBF19 Favourites

TUESDAY 12 MAR 2019 10:45 Will Books of the Future Edit Themselves? to 11:15 The Buzz Theatre 11:30 Scholarly Publishing Comes of Age - Where are You on the Journey to 12:30 to Data Maturity? The Faculty 11:45 How to Make a Living from Writing to 12:30 Author HQ 13:00 Making a Great First Impression to 13:30 Author HQ 13:00 Creative Commons Explained to 14:00 The Faculty 13:15 Illustrator of the Fair, David McKee in Conversation with Ren to 13:45 Renwick, The Association of Illustrators (AOI) Fireside Chats @ The Podcast Theatre 13:15 European Literary Voices: A Conversation with Antoine Laurain, to 14:15 France; Simone Buchholz, Germany and Stefan Hertmans, Belgium. English PEN Literary Salon 13:30 Not All E-Books Are Created Equal. The Research Behind What to 14:00 Makes a Good Digital Book. Children's Hub Page 1 of 14 14:30 Turning Yourself Into A Brand to 15:30 Author HQ 15:30 Brand Licensing for Publishers – Turning Your Book IP into a to 16:30 Consumer Product Range The Buzz Theatre 15:45 Publishing Trends in 2018 to 16:15 Author HQ 16:30 Book Brunch Selfie Awards to 17:30 Author HQ WEDNESDAY 13 MAR 2019 09:45 How to Successfully Self-Publish to 10:30 Author HQ 10:00 Truth and Lies – Academic Publishing in the Era of Fake News to 11:00 The Faculty 10:00 Green Bookseller: Practical Steps for Booksellers and How the to 11:00 Industry Could Minimise Waste High Street Theatre 10:00 Getting the Most for Your Audio Rights to 11:00 Club Room, National Hall Gallery Page 2 of 14 10:45 An Introduction to Kindle Direct Publishing: Finding Readers. -

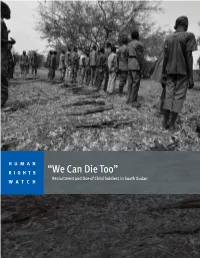

Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in South Sudan WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS “We Can Die Too” Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in South Sudan WATCH “We Can Die Too” Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in South Sudan Copyright ©2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-33092 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2015 978-1-6231-33092 “We Can Die Too” Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in South Sudan Map of South Sudan .......................................................................................................... i Glossary .......................................................................................................................... ii Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .......................................................................................................... -

Myanmar (Burma): a Reading Guide Andrew Selth

Griffith Asia Institute Research Paper Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide Andrew Selth i About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally recognised research centre in the Griffith Business School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding commitment and future aspirations for the study of and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific— cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s Asia-Pacific future. We do this by: i) conducting and supporting excellent and relevant research on the politics, security, economies and development of the Asia-Pacific region; ii) facilitating high level dialogues and partnerships for policy impact in the region; iii) leading and informing public debate on Australia’s place in the Asia Pacific; and iv) shaping the next generation of Asia-Pacific leaders through positive learning experiences in the region. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Research Papers’ publish the institute’s policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asia-institute ‘Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide’ February 2021 ii About the Author Andrew Selth Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University. He has been studying international security issues and Asian affairs for 45 years, as a diplomat, strategic intelligence analyst and research scholar. Between 1974 and 1986 he was assigned to the Australian missions in Rangoon, Seoul and Wellington, and later held senior positions in both the Defence Intelligence Organisation and Office of National Assessments. -

A Return of Hostilities? Comprehensive Peace Agreement, Transformational Challenge and the Future of Sudan

June 2011 A return of Hostilities? Comprehensive Peace Agreement, Transformational Challenge and the Future of Sudan. Aalborg University Dept. of History, International & Social Studies Development and International Relations Master’s Thesis 10 th semester Submitted by Wilfred Segun Iyekolo 080679-4031 Supervisor: Prof. Mammo Muchie i | P a g e Table of Content Table of Content i List of Abbreviations ii Acknowledgement iii Abstract iv Map of Sudan v Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Statement of the Problem 3 1.2 Justification of the Problem Field 5 1.3 Research Questions 5 1.4 Research Design 6 1.5 Methodological Consideration 7 1.6 Objective of Study 8 1.7 Assumptions 8 1.8 Nature of Study and Data Analysis Procedure 8 1.9 Use of Theory 9 1.10 Scope and Limitation of Study 11 1.11 Sources of Knowledge 11 1.12 Literature Review 11 Chapter 2: Theoretical & Conceptual Framework 15 2.0 Introduction 15 2.1 Social Identity Theory [SIT] 15 2.2 Theory of Political Development 18 2.3 Conceptual Framework 22 2.3.1 Peace Agreement Implementation 23 Mediationalists Perspective 24 Mutual Vulnerability Perspective 28 2.3.2 Authoritarian Governance 32 Chapter 3: Background to the Sudan Comprehensive Peace Agreement 37 3.0 Introduction 37 3.1 Origin and Causes of Sudan North-South Conflict 37 3.2 Provisions of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement 41 Chapter 4 : The long road from Naivasha : Contending Objectives and Issues in the 46 Comprehensive Peace Agreement Implementation 4.0 Introduction 46 4.1 CPA Objectives 46 4.1.1 CPA Actors 49 4.1.2 CPA Negotiation 50 4.1.3 CPA Implementation 54 4.2 So far, so good? A Brief Assessment of the CPA 59 ii | P a g e Chapter 5 : Sudan, Impotency of the CPA and Contending Transformational 61 Challenges. -

South Sudan: Compounding Instability in Unity State

SOUTH SUDAN: COMPOUNDING INSTABILITY IN UNITY STATE Africa Report N°179 – 17 October 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. STATE ORIGINS AND CHARACTERISTICS ............................................................ 1 III. LEGACY OF WAR ........................................................................................................... 3 IV. POLITICAL POLARISATION AND A CRISIS OF GOVERNANCE ...................... 4 A. COMPLAINTS LODGED ................................................................................................................. 5 B. PARTY POLITICS: A HOUSE DIVIDED ........................................................................................... 6 C. TENSE GUBERNATORIAL ELECTION ............................................................................................. 7 D. THE DIVIDE REMAINS .................................................................................................................. 8 V. NATIONAL POLITICS AT PLAY ................................................................................. 8 VI. REBEL MILITIA GROUPS AND THE POLITICS OF REBELLION .................... 10 A. MILITIA COMMANDERS AND FLAWED INTEGRATION ................................................................. 11 B. THE STAKES ARE RAISED: PETER GADET ..................................................................................