WILSON, WALLACE, MFA. for a Second Time Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Generalife Gardens, Alhambra, Granada, 1991

A N I mortar rake glove sausan broom basin sansui First Book, Three Gardens of Andalucfa by Gerry Shikatani mortar rake glove sausan broom basin sansui The title of this book employs one Arabic and one Japanese word: the Arabic sausan (white lily); and Japanese sansui (beautiful landscape). forEsther y Andres Joaquin y Bonnie Editor Sharon Thesen Managing Editor Carol L. Hamshaw Manuscript Editors Daphne Marlatt Steven Ross Smith Contributing Editors Pierre Coupey Ryan Knighton Jason LeHeup Katrina Sedaros George Stanley Cover Design Marion Llewellyn The CapilanoReview is published by The Capilano Press Society. Canadian subscription rates for one year are $25 CST included for individuals. Institutional rates are $30 plus CST. Address correspondence to The Capilano Review, 2055 Purcell Way, North Vancouver, British Columbia V7J 3H5. Subscribe online at www.capcollege.bc.ca/ dept/TCR or through the CMPA at magOmania, www.magomania.com. The Capilano Reviewdoes not accept simultaneous submissions or previously pub lished work. U.S. submissions should be sent with Canadian postage stamps, international reply coupons, or funds for return postage - not U.S. postage stamps. The Capilano Reviewdoes not take responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts. Copyright remains the property of the author or artist. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the author or artist. The Capilano Reviewgratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Capilano College, the Canada Council forthe Arts, and its Friends and Benefactors. The Capilano Reviewis a member of the Canadian Magazine Publishers Association and the BC Association of Magazine Publishers. TCR is listed with the Canadian Periodical Index, with the American Humanities Index, and available online through InfoGlobe. -

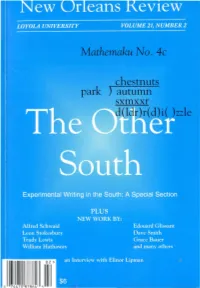

Mathemaku No. 4C

Mathemaku No. 4c chestnuts park ) autumn zzle 0 2 > o 74470 R78fl4 ~ New Orleans Review Summer 1995 Volume 21, Number 2 Editor Associate Editors Ralph Adamo Sophia Stone Cover: poem, "Mathemaku 4c," by Bob Grumman. Michelle Fredette Art Editor Douglas MacCash New Orleans Review is published quarterly by Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118, United States. Copyright© 1995 by Loyola Book Review Editor Copy Editor University. Mary A. McCay T.R. Mooney New Orleans Review accepts submissions of poetry, short fiction, essays, and black and white art work or photography. Translations are also welcome but must be accompanied by the work in its original language. All submis Typographer sions must be accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope. Al John T. Phan though reasonable care is taken, NOR assumes no responsibility for the loss of unsolicited material. Send submissions to: New Orleans Review, Box 195, Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118. Advisory/Contributing Editors John Biguenet Subscription rates: Individuals: $}8.00 Bruce Henricksen Institutions: $21.00 William Lavender Foreign: $32.00 Peggy McCormack Back Issues: $9.00 apiece Marcus Smith Contents listed in the PMLA Bibliography and the Index of American Periodical Verse. Founding Editor US ISSN 0028-6400 Miller Williams New Orleans Review is distributed by: Ingram Periodicals-1226 Heil Quaker Blvd., LaVergne, TN 37086-7000 •1-800-627-6247 DeBoer-113 East Centre St., Nutley, NJ 07110 •1-201-667-9300 Thanks to Julia McSherry, Maria Marcello, Lisa Rose, Mary Degnan, and Susan Barker Adamo. Loyola University is a charter member of the Association of Jesuit University Presses (AJUP). -

Scholarworks@UNO Lost

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-19-2017 Lost Nathaniel Kostar the university of new orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Kostar, Nathaniel, "Lost" (2017). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2332. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2332 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lost A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Poetry by Nathaniel Kostar B.A. Rutgers University, 2008 May 2017 Copyright 2017, Nathaniel Kostar. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to John Gery for your advice and mentorship throughout this process, and to Peter Thompson and Kay Murphy for serving on my thesis committee. Thanks also to my family—who never questioned why I roamed, to the musicians I’ve had the chance to work with in New Orleans, and the venues that let us play their stages. -

Diversity of K-Pop: a Focus on Race, Language, and Musical Genre

DIVERSITY OF K-POP: A FOCUS ON RACE, LANGUAGE, AND MUSICAL GENRE Wonseok Lee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Kristen Rudisill © 2018 Wonseok Lee All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Since the end of the 1990s, Korean popular culture, known as Hallyu, has spread to the world. As the most significant part of Hallyu, Korean popular music, K-pop, captivates global audiences. From a typical K-pop artist, Psy, to a recent sensation of global popular music, BTS, K-pop enthusiasts all around the world prove that K-pop is an ongoing global cultural flow. Despite the fact that the term K-pop explicitly indicates a certain ethnicity and language, as K- pop expanded and became influential to the world, it developed distinct features that did not exist in it before. This thesis examines these distinct features of K-pop focusing on race, language, and musical genre: it reveals how K-pop groups today consist of non-Korean musicians, what makes K-pop groups consisting of all Korean musicians sing in non-Korean languages, what kind of diverse musical genres exists in the K-pop field with two case studies, and what these features mean in terms of the discourse of K-pop today. By looking at the diversity of K-pop, I emphasize that K-pop is not merely a dance- oriented musical genre sung by Koreans in the Korean language. -

He Courier-Gazette Thursday

Issued TVesdav Thursday Thurs ner Issue Saturday he Courier-gazette Entered u Second Claas Mall Matter THREE CENTS A COPY Established January, 1846. By The Courier-Gazette, 465 Main St. Rockland, Maine, Thursday, November 25, 1937 Volume 92.................. Number 141. The Courier-Gazette HE WANTS TO KNOW TIIREE-TIMES-A-WEEK If Representative Smith of Maine A SHORTAGE OF CLAMS COUNTED THE FIRE ALARM ONE BIG HAPPY DAY Editor cannot get a satisfactory reason from WM. O. FULLER tne Social Security Board why fed Associate Editor eral contribution to the needy blind Com’r Feyler Says Situation Is Acute and Hints Then Charlie Taylor Went At His Subject Like a Camden Outing Club Hasn’t Overlooked a Single FRANK A WINSLOW In Maine are not being made, he will Subscriptions S3 oo per year payable ln seek a resolution of inquiry, he said, advance; single copies three cents. At Stern Measures House Afire—Crusade Nearing Its Climax Bet For Next Wednesday Advertising rates based upon circula- He has communicated this position tion and very »to the Social Secuity Board in Wash- NEWSPAPEB HISTORY ' Thc RocXland oazette was established 'r'8t°ni. D. C., saying that he has A shortage of clams available for ing a long time clam program and “Let us stop and count the num mean to take up the cross and fol Next Wednesday, Dec. are from the merchants’ new Christ- in 1346 in 1874 the Courier was estau- always been interested in old age the canning factories in Washington, that he hoped to offer some construc- 1, Camden Commandery mas stock, and each winner will re- Ilshed and consolidated with the Oazette . -

Central Florida Future, Vol. 15 No. 20, February 18, 1983

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 2-18-1983 Central Florida Future, Vol. 15 No. 20, February 18, 1983 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 15 No. 20, February 18, 1983" (1983). Central Florida Future. 498. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/498 E ll BRAR~ ARCHIVES D Analyzing cults, see page 3 D UCF baseball swinging into season, see Sportsweek, page 15 FUTURE D TV talk: Wayne Starr views two new series, see Encore, page 11 Serving the UCF Community for 15 Years • Advisement, 0-Team threatened by Michael Griffin outlook for the coming year "is not tivity and Service Fees to pay for Editor In chief very bright." th~ progr.am. The 0-Team is Peer Advisement's traditional operating now at a deficit of $10,100 Federal and state budget cuts will funding through UCF's Financial accorcling to Jimmie Ferrell, Stu force the cancellation of UCF's Aid Office will be cut next year due dent Center director. Orientation Team and Peer Advise to the Reagan Admin\stration's cuts · ·"There are enough people in SG . -

Guide to the Melba Liston Collection

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago CBMR Collection Guides / Finding Aids Center for Black Music Research 2020 Guide to the Melba Liston Collection Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cmbr_guides Part of the History Commons, and the Music Commons Columbia COLLEGE CHICAGO CENTER FOR BLACK MUSIC RESEARCH COLLECTION The Melba Liston Collection, 1941-1999 EXTENT 44 boxes, 81.6 linear feet COLLECTION SUMMARY The Melba Liston Collection primarily documents her careers as arranger, composer, and educator rather than her accomplishments as a trombonist. It contains lead sheets to her own and other people’s compositions and manuscript scores of many of her arrangements for Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry, and Mary Lou Williams, among others. One extensive series contains numerous arrangements for Randy Weston, and her late computer scores for him are also present. PROCESSING INFORMATION The collection was processed, and a finding aid created, by Kristin McGee in 2000 and the finding aid was updated by Laurie Lee Moses in 2010 and Heidi Marshall in 2020. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Melba Liston was a jazz composer, arranger, and performer born in 1926. She was a trombonist during an era (1942–1985) when few women played brass instruments and even fewer toured with jazz bands. She played in the bands of several important jazz musicians, including Count Basie, Dexter Gordon, Dizzy Gillespie, Charles Mingus, Randy Weston, and Quincy Jones. Liston had an active career as an arranger for important jazz composers as well as popular music record labels. She also worked with youth orchestras in the troubled neighborhood of Watts, California, leaving the United States to teach at the Jamaica Institute of Music for six years (1973–1979). -

Inscape 2008

-c * ' •nscaDn 2DD8 ART &UTERARY MAGAZll , This issue is dedicated to Erica Lee Brown. IN·SCAPE lN.J The essential, distinctive, and revolutionary quality ofa thing: "Here is the inscape, the epiphany, the moment oftruth." (Madison Smartt Bell). inscape • 1 STAFF FACULTY ADVISORS George Eklund Chris Holbrook Rebecca Howell Elizabeth Mesa-Gaido Gary Mesa-Gaido Crystal Wilkinson EDITOR Alex Schulz EDITORIAL BOARD Ryan Andersons David Collins Stephen Graham Jessica Herrington Brandon Massengill Journey McAndrews William Salazar Craig Wagner COVER DESIGN David V Moore SPECIAL THANKS To Morehead State University (MSU) Department ofArt MSU Department ofEnglish, Foreign Languages & Philosophy MSU Office of Communications & Marketing MSU Interdisciplinary Women's Studies Program Kentucky Philological Association inscape · 2 CONTENTS POETRY Brandon Massengill Grey Words ............................................................................................................ 7 Lilith III ..................................................................................................................... 9 Sean Corbin Ode to the Abandoned Record Player................................................ 11 (Student Poetry Award) Perverted .................................................................................................................. 12 Journey McAndrews New York is Dead .............................................................................................. 12 The Single Hound ............................................................................................ -

Quercus 2018

Quercus a journal of literary and visual art Volume 27 2018 (kwûrkûs) Latin. (n.) The oak genus: a deciduous hardwood tree or shrub Editor: Christopher Murphey Assistant Editor: Sarah Thilenius Literary Editor: Margaret Shanks Advisor: Carl Herzig Editorial Staff: Cassie Hall Seth Hankins William Hibbard Sam Holm Miranda Liebsack Celeste McKay Abbigail McWilliams Mary Roche Jaren Schoustra 1 Copyright © 2018 by Quercus All rights retained by the authors and artists. Quercus publishes creative writing and artwork by St. Ambrose University students, faculty, staff, and alumni. Address questions, orders, and submissions to [email protected] or Quercus, St. Ambrose University, 518 W. Locust St., Davenport, Iowa 52803. cover image: Stella Herzig Waiting Digital photograph, 2018 Opening excerpt by Darian Auge (’17). Special thanks to Chris Reno. 2 words Fall Leaves Abbigail McWilliams 9 Suspirium Olivia McDonald (’16) 10 Last Night Hannah Blaser (’17) 12 Summer Storm 13 Coal Valley, Illinois 14 we leave the air conditioning Bailey Keimig (’15) 16 off all summer dead ends 18 her lips Mary Roche 20 Stolen Fruit Tastes Better Mariah Morrissey 22 When Eaten by the Mississippi Bucket List 24 Vermin Emily Kingery 26 Plague 27 roots Sarah Holst (’11) 29 sing the sun awake 30 Miriam and Sheshan 32 The Year the Drought Broke 40 Fragility Nancy Hayes 63 Bipolar Bees Maranda Bussell 67 Monday Nights Carmen Martin 68 More Precise Than a Sinner Jeremy Burke (’99) 69 An Apology Anna Badamo 71 The Pastor’s Son Jaren Schoustra 72 The Coercion of Saint Paul John -

Accel World . Altima.Burst the Gravity

ANIME Serie Tipo Artista/Titulo OP Arrival of Tears 11 eyes ENDING Asriel - Sequentia (TV) Accel World . OP Altima.Burst The Gravity (TV) Air ENDING Lia - Farewell Song (TV) OP Air TV - Tori no Uta [VIDEO] Akame ga Kill! ENDING Miku Sawai - Konna Sekai, Shiritakunakatta (TV) OP Sora Amamiya - Skyreach (TV) Aldnoah Zero. OP Kalafina - Heavenly blue (TV) Amnesia. OP Nagi Yanagi - Zoetrope (TV) Angel Beats ENDING Aoi Tada - Brave Song (TV) INSERT SONG Girls Dead Monster - Answer Song INSERT SONG Girls Dead Monster - Thousand Enemies OP Lia - My Soul, Your Beats (TV) Angelic Layer. OP Atsuko Enomoto - Be My Angel Anohana OP Galileo Galilei - Aoi Shiori OP Galileo Galilei - Circle Game (TV) Another. OP Another. Ali Project - Kyoumu Densen (TV) OP Ali Project - Kyoumu Densen Ao no exorcist ENDING 2PM - Take Off ENDING Meisa Kuroki - Wired Life (TV) OP ROOKiEZ is PUNK'D - In My World (TV) OP Uverworld - Core Pride (TV) Aoki Hagane no Arpeggio OP nano feat. MY FIRST STORY - SAVIOR OF SONG OP nano feat. MY FIRST STORY - SAVIOR OF SONG (TV) ENDING Trident - Innocent Blue (TV) ENDING Trident - Blue Fields (TV) Arata Kangatari. OP Sphere - Genesis Aria (TV) OP Sphere - Genesis Aria Argevollen OP Kotoko - Tough Intention (TV) Arjuna ENDING Maaya Sakamoto – Mameshiba ENDING Maaya Sakamoto – Mameshiba (TV) ENDING Maaya Sakamoto - Sanctuary (TV) Asu No Yoichi. OP Meg Rock - Egao No Riyuu (TV) Avenger op. OP Ali Project - Gesshoku Grand Guignol (TV) Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu end.Milktub – ENDING Baka Go Home (TV) Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Irohanihoheto OP OP.FictionJunction YUUKA - Kouya Ruten (TV) OP OP.FictionJunction YUUKA - Kouya Ruten Bakumatsu Rock OP vistlip - Jack (TV) Basilisk ENDING BasiliskNana Mizuki - Wild Eyes (TV) OP Kouga ninpou chou (VIDEO) (Full version) OP Kouga ninpou chou (VIDEO) (TV version) Beck OP Hit in USA Beelzebub ENDING 9nine - Shoujo Traveler (TV) ENDING no3b - Answer (TV) ENDING Shoko Nakagawa - Tsuyogari (TV) Black bullet . -

Storm Cycle 2014 Anthology — Ebook File

Storm Cycle 2014 The Best of Kind of a Hurricane Press Edited by: A.J. Huffman and April Salzano ii Cover Art: “Breaking the Blue” by A.J. Huffman Copyright © 2015 A.J. Huffman All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher: Kind of a Hurricane Press www.kindofahurricanepress.com [email protected] iii CONTENTS Thank You from the 2 Editors From the 2014 Editor’s Choice Contest Winners Donna Barkman Scavenger Hunt 4 Denise Weuve Visitation Tuesday 7 Christopher Hivner Mathematics 9 Mary ewell The Traffic in Old Ladies 12 Alexis Rhone Fancher this small rain 14 Terri Simon Signs of the Apocalypse 16 From the 2014 Pushcart Prize ominees Michael H. Brownstein Before the Winter Storm 18 Drifted East Theresa Darling Another Departure 19 Amanda Kabak Common Grounds 20 Marla Kessler Twenty Eight Seconds 22 Emily Pittman ewberry Signs 24 Leland Seese Until ext Time 25 From the 2014 Best of the et ominees Ben Rasnic Urban Still Life 27 Richard Schnap Domestic Dispute 28 Marianne Szlyk Walking Past Mt. Calvary 29 Cemetery in Winter Jon Wesick A Postindustrial Romance 30 Joanna M. Weston I Meant to Tell You 31 Deborah L. Wymbs Spooning 33 From The Anthologies Sheikha A Alzheimer’s 35 Amanda Anastasi Half-Past 36 Steve Ausherman Closing Time 37 Mary Jo Balistreri The Steaming Cup Café 38 Coffee at the Double Perk 39 Pattie Palmer-Baker The Truth About Dahlias 40 David J. -

Tell It Slant

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2011 Tell it Slant Andrea Ribaudo CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/66 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Tell It Slant Andrea Ribaudo November 17, 2010 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts of the City College of the City University of New York 1 Tell It Slant: Collection 2010 Andrea Ribaudo October 2011/Counting Seven years (give or take) since Dad died. Six years (just about) since first day of college, orientation, undergrad. Five years since Mom really started talking again, really. Four years since Eva started researching, talking, planning the Peace Corps, so seriously. Four years since I started writing again. Three (two and a half?) since Carlos and John and that bar. two years, six months since Eva left. two years of Brent (only two, only two). One year since Mom. Since Mom. Sisters/Daughters. Backwards and forwards. October 2011 She left in April before I knew what to say, before either of us did. We drove to the airport in silence. Past battles and wars floated above our heads, crowding the car. Hypothetical arguments echoed in our minds, ready to slip out of our mouths, so we kept them shut.