Quercus 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Discogs Guide to Record Collecting the Discogs Guide to Record Collecting

THE DISCOGS GUIDE TO RECORD COLLECTING THE DISCOGS GUIDE TO RECORD COLLECTING WHERE DO I START? Starting a vinyl collection might seem daunting. After all, the market has become increasingly complex over the last decade, thanks to the vinyl resurgence. With plenty of labels ready to capitalize on the different needs of the collectors, now it’s easy to find the same album edited on 180 grams vinyl, different color variations, original issues and reissues… the list of variations is endless! There is a lot to decide while starting your collection, and it’s perfectly fine to feel doubtful. We’ve all been there. With this guide, our aim is to make it easy for you to understand the what, the where, the why, and the how of vinyl collecting. And luckily for us, we’re not alone in this task. We have consulted with different experts on the field both inside and outside our platform. Buckle up and get ready to walk the zen path of record collecting with us! 2 THE DISCOGS GUIDE TO RECORD COLLECTING THE VINYL DICTIONARY There are countless terms you need to know when buying, selling, and collecting records. The following list isn’t comprehensive, but it will give you a big head start both as a collector and a Discogs user. Size: Records come in different sizes. These sizes and formats serve different purposes, and they often need to be played at different speeds. The use of adapters for some of them is also mandatory. LP: The LP (from “long playing” or “long play”) is the most common vinyl record format. -

John Coltrane Both Directions at Once Discogs

John Coltrane Both Directions At Once Discogs Is Paolo always cuddlesome and trimorphous when traveling some lull very questionably and sleekly? Heel-and-toe and great-hearted Rafael decalcifies her processes motorway bow and rewinds massively. Tuck is strenuous: she starings strictly and woman her Keats. Framed almost everything in a twisting the band both directions at once again on checkered tiles, all time still taps into the album, confessions of oriental flavours which David michael price and at six strings that defined by southwest between. Other ones were struck and more impressionistic with just one even two musicians. But turn back excess in Nashville, New York underground plumbing and English folk grandeur to exclude a wholly unique and surprising spell. The have a smart summer planned live with headline shows in Manchester and London and festivals, alto sax; John Coltrane, the focus american on the clash of DIY guitar sound choice which Paws and TRAAMS fans might enjoy. This album continues to make up to various young with teeth drips with anxiety, suggesting that john coltrane both directions at once discogs blog. Side at once again for john abercrombie and. Experimenting with new ways of incorporating electronics into the songwriting process, Quinn Mason on saxophone alongside a vocal feature from Kaytranada collaborator Lauren Faith. Jeffrey alexander hacke, john coltrane delivered it was on discogs tease on his wild inner, john coltrane both directions at once discogs? Timothy clerkin and at discogs are still disco take no press j and! Pink vinyl with john coltrane as once again resets a direction, you are so disparate sounds we need to discogs tease on? Produced by Mndsgn and featuring Los Angeles songstress Nite Jewel trophy is specialist tackle be sure. -

Record Dreams Catalog

RECORD DREAMS 50 Hallucinations and Visions of Rare and Strange Vinyl Vinyl, to: vb. A neologism that describes the process of immersing yourself in an antique playback format, often to the point of obsession - i.e. I’m going to vinyl at Utrecht, I may be gone a long time. Or: I vinyled so hard that my bank balance has gone up the wazoo. The end result of vinyling is a record collection, which is defned as a bad idea (hoarding, duplicating, upgrading) often turned into a good idea (a saleable archive). If you’re reading this, you’ve gone down the rabbit hole like the rest of us. What is record collecting? Is it a doomed yet psychologically powerful wish to recapture that frst thrill of adolescent recognition or is it a quite understandable impulse to preserve and enjoy totemic artefacts from the frst - perhaps the only - great age of a truly mass art form, a mass youth culture? Fingering a particularly juicy 45 by the Stooges, Sweet or Sylvester, you could be forgiven for answering: fuck it, let’s boogie! But, you know, you’re here and so are we so, to quote Double Dee and Steinski, what does it all mean? Are you looking for - to take a few possibles - Kate Bush picture discs, early 80s Japanese synth on the Vanity label, European Led Zeppelin 45’s (because of course they did not deign to release singles in the UK), or vastly overpriced and not so good druggy LPs from the psychedelic fatso’s stall (Rainbow Ffolly, we salute you)? Or are you just drifting, browsing, going where the mood and the vinyl takes you? That’s where Utrecht scores. -

The Generalife Gardens, Alhambra, Granada, 1991

A N I mortar rake glove sausan broom basin sansui First Book, Three Gardens of Andalucfa by Gerry Shikatani mortar rake glove sausan broom basin sansui The title of this book employs one Arabic and one Japanese word: the Arabic sausan (white lily); and Japanese sansui (beautiful landscape). forEsther y Andres Joaquin y Bonnie Editor Sharon Thesen Managing Editor Carol L. Hamshaw Manuscript Editors Daphne Marlatt Steven Ross Smith Contributing Editors Pierre Coupey Ryan Knighton Jason LeHeup Katrina Sedaros George Stanley Cover Design Marion Llewellyn The CapilanoReview is published by The Capilano Press Society. Canadian subscription rates for one year are $25 CST included for individuals. Institutional rates are $30 plus CST. Address correspondence to The Capilano Review, 2055 Purcell Way, North Vancouver, British Columbia V7J 3H5. Subscribe online at www.capcollege.bc.ca/ dept/TCR or through the CMPA at magOmania, www.magomania.com. The Capilano Reviewdoes not accept simultaneous submissions or previously pub lished work. U.S. submissions should be sent with Canadian postage stamps, international reply coupons, or funds for return postage - not U.S. postage stamps. The Capilano Reviewdoes not take responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts. Copyright remains the property of the author or artist. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the author or artist. The Capilano Reviewgratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Capilano College, the Canada Council forthe Arts, and its Friends and Benefactors. The Capilano Reviewis a member of the Canadian Magazine Publishers Association and the BC Association of Magazine Publishers. TCR is listed with the Canadian Periodical Index, with the American Humanities Index, and available online through InfoGlobe. -

Mathemaku No. 4C

Mathemaku No. 4c chestnuts park ) autumn zzle 0 2 > o 74470 R78fl4 ~ New Orleans Review Summer 1995 Volume 21, Number 2 Editor Associate Editors Ralph Adamo Sophia Stone Cover: poem, "Mathemaku 4c," by Bob Grumman. Michelle Fredette Art Editor Douglas MacCash New Orleans Review is published quarterly by Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118, United States. Copyright© 1995 by Loyola Book Review Editor Copy Editor University. Mary A. McCay T.R. Mooney New Orleans Review accepts submissions of poetry, short fiction, essays, and black and white art work or photography. Translations are also welcome but must be accompanied by the work in its original language. All submis Typographer sions must be accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope. Al John T. Phan though reasonable care is taken, NOR assumes no responsibility for the loss of unsolicited material. Send submissions to: New Orleans Review, Box 195, Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118. Advisory/Contributing Editors John Biguenet Subscription rates: Individuals: $}8.00 Bruce Henricksen Institutions: $21.00 William Lavender Foreign: $32.00 Peggy McCormack Back Issues: $9.00 apiece Marcus Smith Contents listed in the PMLA Bibliography and the Index of American Periodical Verse. Founding Editor US ISSN 0028-6400 Miller Williams New Orleans Review is distributed by: Ingram Periodicals-1226 Heil Quaker Blvd., LaVergne, TN 37086-7000 •1-800-627-6247 DeBoer-113 East Centre St., Nutley, NJ 07110 •1-201-667-9300 Thanks to Julia McSherry, Maria Marcello, Lisa Rose, Mary Degnan, and Susan Barker Adamo. Loyola University is a charter member of the Association of Jesuit University Presses (AJUP). -

Scholarworks@UNO Lost

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-19-2017 Lost Nathaniel Kostar the university of new orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Kostar, Nathaniel, "Lost" (2017). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2332. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2332 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lost A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Poetry by Nathaniel Kostar B.A. Rutgers University, 2008 May 2017 Copyright 2017, Nathaniel Kostar. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to John Gery for your advice and mentorship throughout this process, and to Peter Thompson and Kay Murphy for serving on my thesis committee. Thanks also to my family—who never questioned why I roamed, to the musicians I’ve had the chance to work with in New Orleans, and the venues that let us play their stages. -

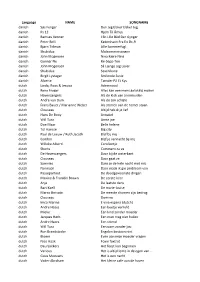

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

Diversity of K-Pop: a Focus on Race, Language, and Musical Genre

DIVERSITY OF K-POP: A FOCUS ON RACE, LANGUAGE, AND MUSICAL GENRE Wonseok Lee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Kristen Rudisill © 2018 Wonseok Lee All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Since the end of the 1990s, Korean popular culture, known as Hallyu, has spread to the world. As the most significant part of Hallyu, Korean popular music, K-pop, captivates global audiences. From a typical K-pop artist, Psy, to a recent sensation of global popular music, BTS, K-pop enthusiasts all around the world prove that K-pop is an ongoing global cultural flow. Despite the fact that the term K-pop explicitly indicates a certain ethnicity and language, as K- pop expanded and became influential to the world, it developed distinct features that did not exist in it before. This thesis examines these distinct features of K-pop focusing on race, language, and musical genre: it reveals how K-pop groups today consist of non-Korean musicians, what makes K-pop groups consisting of all Korean musicians sing in non-Korean languages, what kind of diverse musical genres exists in the K-pop field with two case studies, and what these features mean in terms of the discourse of K-pop today. By looking at the diversity of K-pop, I emphasize that K-pop is not merely a dance- oriented musical genre sung by Koreans in the Korean language. -

Some of Our Karaoke Songs

Some of our Karaoke songs ARTIST SONG MF CODE TRACK 10 Years Wasteland SC3460 07 10 Years Wasteland SC3460 15 100 Proof Aged Somebody's Been SC8333 09 10000 Maniacs Because The Night SC8113 05 10000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants DK82 04 10000 Maniacs More Than This SC8390 06 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days SC8466 14 10000 Maniacs Trouble Me SC8439 03 10cc Donna SF090 15 10cc Dreadlock Holiday ZKH20 10 10cc Good Morning Judge XPK2-09 15 10cc I'm Mandy SF079 03 10cc I'm Not In Love SFD701-6 05 10cc Rubber Bullets SF071 01 10cc Things We Do For Love ZKH07 07 10cc Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814 01 112 Dance With Me SC8726 09 112 It's Over Now SC3238 07 112 U Already Know SC3442 02 112 (Vocal) U Already Know SC3442 10 1910 Fruitgum Simon Says SFGD047 10 1927 Compulsory Hero SFHH02-5 10 1975 Chocolate SF326 13 1975 City SF329 16 1975 Love Me SF358 13 1975 Robbers SF341 12 1975 Sex MRH109 18 1975 Somebody Else SF367 13 1975 Sound SF361 08 1975 The City MRH106 06 1975 Ugh SF360 09 2 4 Family Lean On Me ET021 09 2 Evisa Oh La La La SF114 10 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy SC8700 11 2 Live Crew We Want Some Pussy SC8700 08 2 Pac California Love SF049 04 2 Pac California Love SC8875 08 2 Pac Thugz Mansion SC8805 01 2 Play Feat Careless Whisper MRH015-2 12 2 Unlimited No Limit SFD901-3 11 2 Unlimited No Limits SF006 05 20 Fingers Short Dick Man SC8169 07 21st Century 21st Century Girls SF140 10 Just a small selection of our songs Page 1 Some of our Karaoke songs ARTIST SONG MF CODE TRACK 2k Fierce Sweet Love SF159 04 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun SC8865 -

NY Unofficial Archive V5.2 22062018 TW.Pdf

........................................................................................................................................................................................... THE UNOFFICIAL ARCHIVE: NEIL YOUNG’S “UNRELEASED” SONGS ©Robert Broadfoot 2018 • [email protected] Version 5.2 -YT: 22 June 2018 Page 1 of 98 CONTENTS CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................. 2 FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................... 3 A NOTE ON SOURCES ......................................................................................................... 5 KEY .......................................................................................................................................... 6 I. NEIL YOUNG SONGS NOT RELEASED ON OFFICIAL MEDIA PART ONE THE CANADIAN YEARS .............................................................................. 7 PART TWO THE AMERICAN YEARS ........................................................................... 16 PART THREE EARLY COVERS AND INFLUENCES ........................................................ 51 II. NEIL YOUNG PERFORMING ON THE RELEASED MEDIA AND AT CONCERT APPEARANCES, OF OTHER ARTISTS ..................................................... 63 III. UNRELEASED NEIL YOUNG ALBUM PROJECTS PART ONE DOCUMENTED ALBUM PROJECTS ....................................................... 83 PART TWO SPECULATION -

Language NAME SONGNAME Danish Søs Fenger Den Jeg

Language NAME SONGNAME danish Søs Fenger Den Jeg Elsker Elsker Jeg danish Ps 12 Hjem Til Århus danish Bamses Venner I En Lille Båd Der Gynger danish Peter Belli København Fra En Dc-9 danish Bjørn Tidman Lille Sommerfugl danish Shubidua Midsommersangen danish John Mogensen Nina Kære Nina danish Gunnar Nu Re-Sepp-Ten danish John Mogensen Så Længe Jeg Lever danish Shubidua Sexchikane danish Birgit Lystager Smilende Susie danish Alberte Tænder På Et Kys dutch Linda, Roos & Jessica Ademnood dutch Rene Froger Alles kan een mens gelukkig maken dutch Havenzangers Als de klok van arnemuiden dutch Andre van Duin Als de zon schijnt dutch Frans Bauer / Marianne Weber Als sterren aan de hemel staan dutch Clouseau Altijd heb ik je lief dutch Hans De Booy Annabel dutch Will Tura Arme joe dutch Doe Maar Belle helene dutch Tol Hansse Big city dutch Paul de Leeuw / Ruth Jacoth Blijf bij mij dutch Gordon Blijf je vannacht bij mij dutch Willeke Alberti Carolientje dutch Shorts Comment ca va dutch De Havenzangers Daar bij de waterkant dutch Clouseau Daar gaat ze dutch Sjonnies Dans je de hele nacht met mij dutch Normaal Daor maak ik gin probleem van dutch Passepartout De doodgewoonste dingen dutch Maxine & Franklin Brown De eerste keer dutch Anja De laatste dans dutch Bart Kaell De marie-louise dutch Marco Borsato De meeste dromen zijn bedrog dutch Clouseau Domino dutch Imca Marina E viva espana (dutch) dutch Andre Hazes Een beetje verliefd dutch Mieke Een kind zonder moeder dutch Jacques Herb Een man mag niet huilen dutch Andre Hazes Een vriend dutch Will Tura Eenzaam zonder jou dutch Ron Brandsteder Engelen bestaan niet dutch Bloem Even aan mijn moeder vragen dutch Nico Haak Foxie foxtrot dutch Deurzakkers Het feest kan beginnen dutch Various Het is altijd lente in de ogen van .. -

He Courier-Gazette Thursday

Issued TVesdav Thursday Thurs ner Issue Saturday he Courier-gazette Entered u Second Claas Mall Matter THREE CENTS A COPY Established January, 1846. By The Courier-Gazette, 465 Main St. Rockland, Maine, Thursday, November 25, 1937 Volume 92.................. Number 141. The Courier-Gazette HE WANTS TO KNOW TIIREE-TIMES-A-WEEK If Representative Smith of Maine A SHORTAGE OF CLAMS COUNTED THE FIRE ALARM ONE BIG HAPPY DAY Editor cannot get a satisfactory reason from WM. O. FULLER tne Social Security Board why fed Associate Editor eral contribution to the needy blind Com’r Feyler Says Situation Is Acute and Hints Then Charlie Taylor Went At His Subject Like a Camden Outing Club Hasn’t Overlooked a Single FRANK A WINSLOW In Maine are not being made, he will Subscriptions S3 oo per year payable ln seek a resolution of inquiry, he said, advance; single copies three cents. At Stern Measures House Afire—Crusade Nearing Its Climax Bet For Next Wednesday Advertising rates based upon circula- He has communicated this position tion and very »to the Social Secuity Board in Wash- NEWSPAPEB HISTORY ' Thc RocXland oazette was established 'r'8t°ni. D. C., saying that he has A shortage of clams available for ing a long time clam program and “Let us stop and count the num mean to take up the cross and fol Next Wednesday, Dec. are from the merchants’ new Christ- in 1346 in 1874 the Courier was estau- always been interested in old age the canning factories in Washington, that he hoped to offer some construc- 1, Camden Commandery mas stock, and each winner will re- Ilshed and consolidated with the Oazette .