Brown Pigmentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mcoa Report Final

REPORT TO ROCKY MOUNTAIN HORSE ASSOCIATION GENETIC SURVEY OF THE PMEL17/ SILVER MUTATION WHICH CAUSES MULTIPLE CONGENITAL OCULAR ANOMALIES (MCOA) Final Draft accepted by RMHA Board: 3 October 2020 Prepared by Noah Anderson Chair, Genetics Committee RMHA Assistant Professor of Biology Winona State University Acknowledgements: Our understanding of MCOA results from the efforts of many people. This disorder has been a part of our breed since the beginning. When reading this report, it would be all too easy to forget that the first study happened over 20 years ago with the cooperation of many bold members of the RMHA and the RMHA itself. Rather than letting politics or popularity of their decisions paralyze them, they chose to face MCOA head on. We owe those people a debt of gratitude for doing the right thing by the horse. This study could have stalled out before it even began if it wasn’t for the dogged determination of David Swan and Steve Autry. David and Steve kept us (the genetics committee) corralled until we understood how important understanding MCOA is to the future of our breed. Steve developed the proposal and laid out the experimental design for this project, then carefully shepherded the project until it was near completion. We are fortunate that Steve is continuing to be a guiding light in our genetics committee, as we work to continue the tradition of doing the right thing by the Rocky Mountain Horse. David passed away while this study was being conducted; we will miss his leadership. Mik Fenn kept me swimming in data from our pedigree database of which he is the expert custodian. -

I . the Color Gene C

THE ABC OF COLOR INHERITANCE IN HORSES W. E. CASTLE Division of Genetics, University of California, Berkeley, California Received October, 27, 1947 HE study of color inheritance in horses was begun in the early days of Tgenetics. Indeed many facts concerning it had already been established earlier, by DARWINin his book on “Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication.” At irregular inteivals since then, new attempts have been made to collect and classify in terms of genetic factors the records contained in stud books concerning the colors of colts in relation to the colors of their sires and dams. A full bibliography is given by CREWand BuCHANAN-SMITH (19301. By such studies, we have acquired very full information as to what color a colt may be expected to have, when the color of its parents and grandparents is known. This knowledge is empirical rather than experimental in nature. For horses being slow breeding and expensive are rarely available for direct experi- mental study, such as can be made with the small laboratory mammals, mice, rats, rabbits and guinea pigs. We have definite information that color inheritance in horses involves the existence of mutant genes similar to those demonstrated by experimental studies to be involved in color inheritance of other mammals. But the horse genes have been given special names, as they were successively discovered, and it is difficult at present to correlate them with the better known names and geneic symbols used by the experimental breeders. The present paper is an attempt to make such a correlation. Just as in morphological studies comparative anatomy was found useful and still is used to establish homologies between systems of organs, so in mammalian genetics, a comparative study of gene action in the production of coat colors and color patterns may also be of value. -

Use of Genomic Tools to Discover the Cause of Champagne Dilution Coat Color in Horses and to Map the Genetic Cause of Extreme Lordosis in American Saddlebred Horses

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Veterinary Science Veterinary Science 2014 USE OF GENOMIC TOOLS TO DISCOVER THE CAUSE OF CHAMPAGNE DILUTION COAT COLOR IN HORSES AND TO MAP THE GENETIC CAUSE OF EXTREME LORDOSIS IN AMERICAN SADDLEBRED HORSES Deborah G. Cook University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cook, Deborah G., "USE OF GENOMIC TOOLS TO DISCOVER THE CAUSE OF CHAMPAGNE DILUTION COAT COLOR IN HORSES AND TO MAP THE GENETIC CAUSE OF EXTREME LORDOSIS IN AMERICAN SADDLEBRED HORSES" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Veterinary Science. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gluck_etds/15 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Veterinary Science at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Veterinary Science by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Cob Or Chimera?

Cob or Chimera? UK Expat Sarah Redstone Lee explains why she believes the Cob Normand to be the most versatile cob of them all nce we had decided to take the The origins of the Normandy Cob can be To this day, the Chateau of Versailles is still plunge, sell up, pack up and traced back to Great Britain, the first ‘Norman’ surrounded by carriage driving Normandy make the move to Normandy; horse, to arrive on our shores was during the Cobs in homage to his passion for the breed. code named Operation transportation of a herd of around 2- 3,000, in The National Stud and home of the Overseas ( as but a small preparations for the battle of Hastings of 1066. Normandy Cob was founded by Napoléon in homage to operation Overlord in Normandy, Much of the success of the invasion depended 1806. By 1840, some of the cobs were crossed Owhich formed part of the D-Day landings), it on the horses that were bred for the endurance with King Henry the VIII’s favourite breed, was not long before my husband and I were required in order to carry the weight of the now extinct Norfolk trotter. This further enjoying la belle vie Francaise. We have been armoured suits, weapons and chain mail, yet the enhanced the look of elegance combined here for almost 10 years now, and, aside from superior among them also possessed great speed. with speed. The standard was set and the benefitting from the usual attractions that The Normans, are even to this day well Normandy Cob was then divided in to two France has to offer, that needs no form of known for their breeding of the Percheron groups; heavier horses for work, and lighter introduction, I have been very privileged to and the French Trotter. -

The Occurrence of Silver Dilution in Horse Coat Colours

ISSN 1392-2130. VETERINARIJA IR ZOOTECHNIKA (Vet Med Zoot). T. 60 (82). 2012 THE OCCURRENCE OF SILVER DILUTION IN HORSE COAT COLOURS Erkki Sild, Sirje Värv and Haldja Viinalass Institute of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences, Estonian University of Life Sciences Kreutzwaldi 1, 51014 Tartu, Estonia; Tel: +372 731 3469; Fax: +372 742 2344; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The MC1R allele “e” in the homozygous state leads to the production of pheomelanin and is responsible for inhibition of expression of the silver dilution gene (PMEL17 “Z” allele). Horse coat colour is one of the traits breeders select for. A total of 133 horses representing Estonian Native (48), Estonian Heavy Draught (40) and Tori (45) breeds were genotyped for key polymorphisms at C901T in MC1R, the 11 bp deletion in ASIP and C1457T in PMEL17 to determine horse coat colour variation and selection possibilities to increase silver-diluted colours. Our genotyping results showed the “ee” genotype frequency in the MC1R gene to be as follows: Estonian Native 45.8%, Estonian Heavy Draught 65.0%, and Tori 77.8%, and the “Z_” genotype in PMEL17 to be 10.4%, 12.5%, and 0.0%, respectively. Six of total 133 horses with silver dilution were examined for MCOA. No eye abnormalities were detected. Considering the PMEL17 gene singly, silver coat colour could be expressed phenotypically in 12% of genotyped Estonian Heavy Draught horses, but due to unfavourable covariation with the MC1R “e” allele, it only occurred in two per cent of horses. Keywords: ASIP, horse coat colour, MC1R, MCOA, PMEL17, silver phenotype. -

19/07/2018 Page 1 of 9 Genetic Screening Tests Available Symbol

Genetic Screening Tests available Symbol Name Description of variant effects Genetic Disease Testing CA is a neurological disorder that affects the cells in the cerebellum, causing head tremors, ataxia and other effects. Affected horses are more likely to fall and are generally not safe to ride. Symptoms appear from 6 weeks to around 4 months old. CA has been linked to a mutation in the TOE1 Cerebellar CA gene and is a recessive disorder, meaning that a horse must Abiotrophy be homozygous (CA/CA) to be affected. If a horse is a carrier (CA/n), it will not show any clinical signs of CA, but it will pass the variant on to approximately half its offspring. Mating to other carriers should be avoided to prevent the birth of an affected foal. LFS causes neurological dysfunction in foals. The symptoms include seizures, hyperextension of the limbs, neck and back, leg paddling, and inability to stand. As the name suggests, LFS also dilutes to the coat to a pale lavender pink or silver colour. The foal will not improve and will die, so it should be euthanised. LFS is a recessive disorder so two copies of the Lavender Foal defective version of the MYO5A gene must be inherited LFS Syndrome (LFS/LFS) for a foal to be affected. If a horse is a carrier (LFS/n), it will not show any clinical signs of LFS. However, there is a 50% chance it will pass the variant to its offspring, so mating to other carriers should be avoided to prevent the birth of an affected foal. -

The Show of Colours

THE SHOW OF COLOURS Celebration of every horse SHOWING CLASSES FOR ALL colour – classes for all WITH EVENING PERFORMANCE SPECTACULAR Sunday 7th July 2019 CLASSES FOR ALL HORSES AND PONIES COLOURED, TWO TONE AND SOLID £13.00 Pre entry £15.00 entry on the day Fun classes £10.00 – pre entry and on the day EVENING PERFORMANCE INCLUDING COLOUR PARADE, CLASS AND COLOUR CHAMPIONSHIPS QUALIFYING SHOW FOR CHAPS (UK) OPPORTUNITY TO GAIN POINTS FOR THE HOWE GRAND FINALE AND STEP TOWARDS THE CHANCE TO WIN £500 FOR YOURSELF AND £500 FOR YOU CHOSEN CHARITY QUALIFYING SHOW FOR OUR NEW ECOSSE ELITE TROPHY FOR SCOTTISH BREEDS THE CHANCE TO WIN £100 FOR YOURSELF AND £100 FOR YOU CHOSEN CHARITY QUALIFYING SHOW FOR THE CALEDONIAN SHOWING CHAMPIONSHIPS Please be aware that “Not Before Times” are only as a guide, classes will not start before these times but may start considerably later depending on entries Pre enter on Equo Pre entries close on 3rd July 2019 THE SHOW OF COLOURS – SUNDAY 7th JULY 2019 Welcome to the schedule of the Show of Colours which run in four rings; Ring 1 - Coloured Ring – for all Skewbald and Piebald Ring 2 -Two Tone Ring – for all Roan, Palomino, Spotted and Dun/Buckskin Ring 3 - Solid Ring – for all Black, Grey, Chestnut and Bay Ring 4 - Fun Ring - for all colours Ring 5 - TGCA Scottish Regional Show - The day of showing classes for all horses and ponies of all breeds and types will culminate in an Evening Performance Spectacular. EVENING PERFORMANCE (not before 4.30pm) CONCOURS DE ELEGANCE COLOUR PARADE Free entry – open to all please take part in hand or ridden, details on next page. -

Horse Coat Color Test Results Dt34839

HORSE COAT COLOR TEST RESULTS TONI PERDEW Case: DT34839 3005 LEXINGTON CT Date Received: 05-Aug-2013 BEDFORD, IA 50833 Report Date: 07-Aug-2013 Report ID: 3263-6964-9709-4059 Verify report at https://www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/myvgl/verify.html Horse: HI JACD SILVER Reg: 5220615 DOB: 05/31/2009 Breed: QH Sex:M Alt. ID: Sire: MAINLY MERLIN Reg: Dam: BAILEYS BADLAND BUCK Reg: W10 DOMINANT RED FACTOR Not requested. Not requested. WHITE SPLASHED AGOUTI Not requested. Not requested. WHITE CREAM Not requested. TOBIANO Not requested. PEARL Not requested. LEOPARD Not requested. SILVER Not requested. GRAY Not requested. Horse is homozygous for the Dun gene. All DUN ROAN Not requested. D/D offspring should be dun dilute. CHAMPAGNE Not requested. LETHAL WHITE Not requested. OVERO SABINO 1 Not requested. For more details on horse coat color tests, please visit: www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/services/coatcolorhorse.php Tests for Gray, Leopard/Appalossa and Lethal White Overo are performed under license. Horse Coat Color Results with Explanations Red Factor Silver e/e - Only the red factor detected. Basic color is sorrel or chestnut in the absence of other N/N - No evidence of the altered sequence detected. modifying genes. N/Z - One copy of the altered sequence detected. Black-based horses will be chocolate with flaxen E/e - Both black and red factors detected. Either E or e transmitted to offspring. Basic color is or lightened mane and tail. Bay-based horses will have lightened black pigment on lower legs, mane black, bay or brown in the absence of other modifying genes. -

Fcanfeun Simon &

Sntngraour* fltrtur* Serttnn (Jfjj Nftll sork ©tttUß fcuniUQ. (irtotu-r fi. iai ADVKBTIMMKNT ADVERTISEMENT. ADVERTISEMENT ADVERTISEMENT ADVERTISEMENT ADVERTISEMENT ADVERTISEMENT fcanfeUn Simon & Co. A Store of Individual Shops Fifth Avenue, 37th and 38th Sts., New York Exclusive Fashions At Special Prices For WOMEN, MISSES and GIRLS ?31?Women'* Fur Trimmed Suit of 47?Women's Fur Trimmed Coat c Duvet de Laine, in navy, brown, taupe, del- phlne, Duvetyn Wool Velour, in navy, bisor reindeer or black; convertible collar brown or reindeer; large draped collar o and pockets with Hudson seal fur (dved natural nutria fur; silk lined, interlinec 79.50 muskrat). 69.50 49?Women's Wrap-Coat (fur trimmed 33?Women'* Fur Trimmed Suit of of Evora Cloth,?in gunmetal, copper Rayonner Silvertone Wool Velour, in naw, seal brown, Congo, navy or black; collar brown, Burgundy or Oxford; TuxuJo cuffs and bands of Hudson seal fur {dyei collar of Hudson seal fur (dyed muskrat). 98.50 muskrnt); silk lined, interlined. 115.00 35 51?Girls' Three-pieceDress navy am Women I Emb'd Georgette Waist plaid Wool of ?navy and bisque, taupe and copen, Serge, coatee of navy serge beaver and or black white pique waist, side-pleated plaid serg copen, and bisque: silk skirt. 12 to years. 15.75 embroidered in self and contrasting color. 14.50 16 53? Girls' Velveteen Dress in naw 37?Women'* Georgette Waist?in new brown or black, two-piece belted mode two-color effects?navy and henna, naw trimmed with black silk braid and coverei and gray, or brown and bisque, emb'd in buttons. -

Quantitative Genetic Analysis of Melanoma and Grey Level in Lipizzan Horses

7th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, August 19-23, 2002, Montpellier, France QUANTITATIVE GENETIC ANALYSIS OF MELANOMA AND GREY LEVEL IN LIPIZZAN HORSES I. Curik1, M. Seltenhammer2 and J. Sölkner3 1Animal Science Department, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Croatia 2Clinic of Surgery and Ophthalmology, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Austria 3Department of Livestock Science, University of Agricultural Sciences Vienna, Austria INTRODUCTION Changes of coat colour in which the "dark (non-grey)" colour present in foals is progressively replaced by grey is a known phenomenon in horses. A similar process is present in humans. The grey coat colour is inherited as a dominant trait and is the characteristic, although not exclusive, colour for some horse breeds (Bowling, 2000). The Lipizzan horse, originally bred for show and parade at the Imperial Court in Vienna, is among those breeds. Unfortunately, melanomas (skin tumours) are more prevalent in grey than in non-grey horses (e.g. Seltenhammer, 2000). The causative relationship for this positive association as well as the molecular basis for both traits (melanoma and grey level) are not known (Rieder, 1999 ; Seltenhammer, 2000). The inheritance of coat colour in horses has been always studied from a qualitative view (Sponenberg, 1996 ; Bowling, 2000). In the present study we quantified the grey level (shade) and estimated the proportion of additive genetic component (heritability in the narrow sense) of this trait. Further, we estimated the genetic relationship between melanoma stages and grey level as well as the additive inheritance of melanoma stages. MATERIAL AND METHODS Horses. Data for this study was collected from 351 grey Lipizzan horses of four national studs (Djakovo – Croatia ; 64 horses, Piber – Austria ; 160 horses, Szilvesvarad – Hungary ; 67 horses and Topol'cianky – Slovakia ; 60 horses). -

Horse Sale Update

Jann Parker Billings Livestock Commission Horse Sales Horse Sale Manager HORSE SALE UPDATE August/September 2021 Summer's #1 Show Headlined by performance and speed bred horses, Billings Livestock’s “August Special Catalog Sale” August 27-28 welcomed 746 head of horses and kicked off Friday afternoon with a UBRC “Pistols and Crystals” tour stop barrel race and full performance preview. All horses were sold on premise at Billings Live- as the top two selling draft crosses brought stock with the ShowCase Sale Session entries $12,500 and $12,000. offered to online buyers as well. Megan Wells, Buffalo, WY earned the The top five horses averaged $19,600. fast time for a BLS Sale Horse at the UBRC Gentle ruled the day Barrel Race aboard her con- and gentle he was, Hip 185 “Ima signment Hip 106 “Doc Two Eyed Invader” a 2009 Billings' Triple” a 2011 AQHA Sorrel AQHA Bay Gelding x Kis Battle Gelding sired by Docs Para- Song x Ki Two Eyed offered Loose Market On dise and out of a Triple Chick by Paul Beckstead, Fairview, bred dam. UT achieved top sale position Full Tilt A consistant 1D/ with a $25,000 sale price. 486 Offered Loose 2D barrel horse, the 16 hand The Beckstead’s had gelding also ran poles, and owned him since he was a foal Top Loose $6,800 sold to Frank Welsh, Junction and the kind, willing, all-around 175 Head at $1,000 or City OH for $18,000. gelding was a finished head, better Affordability lives heel, breakaway horse as well at Billings, too, where 69 head as having been used on barrels, 114 Head at $1,500+ of catalog horses brought be- poles, trails, and on the ranch. -

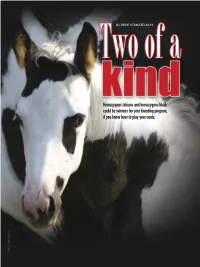

Homozygous Tobiano and Homozygous Black Could Be Winners for Your Breeding Program, If You Know How to Play Your Cards

By IRENE STAMATELAKYS Homozygous tobiano and homozygous black could be winners for your breeding program, if you know how to play your cards. L L I T S K C O T S N N A Y S E T R U O C n poker, a pair is not much to brag gets one of the pair from the sire and the in equine color genetics. If your goal about. Two pairs are just a hair bet - other of the pair from the dam.” is a black foal, and you’ve drawn the ter. But in equine color genetics, a Every gene has an address—a spe - Agouti allele, you’re out of luck. pair—or, even better, two—could cific site on a specific chromosome. be one of the best hands you’ll ever We call this address a locus—plural The Agouti effect hold. We’re talking about a sure bet— being loci. Quite often, geneticists use Approximately 20 percent of horses a pair of tobiano or black genes. the locus name to refer to a gene. registered with the APHA are bay. If Any Paint breeder will tell you that When a gene comes in different you also include the colors derived producing a quality foal that will forms, those variations are called alle - from bay—buckskin, dun, bay roan bring in top dollar is a gamble. In this les. For example, there is a tobiano and perlino—almost one-quarter of business, there are no guarantees. But allele and a non-tobiano allele. Either registered Paints carry and express the what if you could reduce some of the one can occur at the tobiano locus, Agouti allele, symbolized by an upper - risk in your breeding program as well but each chromosome can only carry case A.