Quareia—The Initiate Module I—Core Initiate Skills Lesson 4: Using Mythic Constructs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter Additional Learning Needs and Inclusion

Newsletter Additional Learning Needs and Inclusion FOR THE ATTENTION OF: HEADTEACHERS AND ALN&I CO-ORDINATORS Welcome to the Easter Edition (2017) of the ALN&I Co-ordinators Newsletter. A key objective of the ALN&I Review is improving Communication. It is therefore intended that this newsletter provides you with an up-date of any changes that occur in this field in Gwynedd & Anglesey or nationally. yh ADYaCh d I. 1. General Up-date (Strategy and Legislation) I. The Additional Learning Needs and Inclusion Strategy (ALN&I) Meetings have been held with the staff who are involved in the re-structuring to establish the New ALN&I Service for Gwynedd and Isle of Anglesey. Over 100 staff of the relevant Services attended the 2 open meetings held on 5 October and 6 December 2016; meetings with the relevant Unions were also held during the same period. We are now in the working through the appointments process, and as already confirmed, Gwern ap Rhisiart has been appointed Senior Inclusion Manager and Dr Einir Thomas as Senior ALN Manager; to work across both LEA’s. From the 1st April 2017, we kindly request that you refer matters pertaining to Inclusion matters in Gwynedd and Isle of Anglesey schools to Gwern and ALN related matters to Einir. Gwern ap Rhisiart: 01286 679007 [email protected] Dr Einir Thomas: 01248 752970 [email protected] ALN Responsibility (Einir) Inclusion Responsibility (Gwern) 4 new ALN&I Quality Officers have also been appointed, these officers will support the 2 Senior Managers to implement the ALN&I strategies, and provide managerial advice and support for headteachers and governing bodies. -

“The Prophecies of Fferyll”: Virgilian Reception in Wales

“The Prophecies of Fferyll”: Virgilian Reception in Wales Revised from a paper given to the Virgil Society on 18 May 2013 Davies Whenever I make the short journey from my home to Swansea’s railway station, I pass two shops which remind me of Virgil. Both are chemist shops, both belong to large retail empires. The name-boards above their doors proclaim that each shop is not only a “pharmacy” but also a fferyllfa, literally “Virgil’s place”. In bilingual Wales homage is paid to the greatest of poets every time we collect a prescription! The Welsh words for a chemist or pharmacist fferyllydd( ), for pharmaceutical science (fferylliaeth), for a retort (fferyllwydr) are – like fferyllfa,the chemist’s shop – all derived from Fferyll, a learned form of Virgil’s name regularly used by writers and poets of the Middle Ages in Wales.1 For example, the 14th-century Dafydd ap Gwilym, in one of his love poems, pic- tures his beloved as an enchantress and the silver harp that she is imagined playing as o ffyrf gelfyddyd Fferyll (“shaped by Virgil’s mighty art”).2 This is, of course, the Virgil “of popular legend”, as Comparetti describes him: the Virgil of the Neapolitan tales narrated by Gervase of Tilbury and Conrad of Querfurt, Virgil the magician and alchemist, whose literary roots may be in Ecl. 8, a fascinating counterfoil to the prophet of the Christian interpretation of Ecl. 4.3 Not that the role of magician and the role of prophet were so differentiated in the medieval mind as they might be today. -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

ROBERT GERAINT GRUFFYDD Robert Geraint Gruffydd 1928–2015

ROBERT GERAINT GRUFFYDD Robert Geraint Gruffydd 1928–2015 GERAINT GRUFFYDD RESEARCHED IN EVERY PERIOD—the whole gamut—of Welsh literature, and he published important contributions on its com- plete panorama from the sixth to the twentieth century. He himself spe- cialised in two periods in particular—the medieval ‘Poets of the Princes’ and the Renaissance. But in tandem with that concentration, he was renowned for his unique mastery of detail in all other parts of the spec- trum. This, for many acquainted with his work, was his paramount excel- lence, and reflected the uniqueness of his career. Geraint Gruffydd was born on 9 June 1928 on a farm named Egryn in Tal-y-bont, Meirionnydd, the second child of Moses and Ceridwen Griffith. According to Peter Smith’sHouses of the Welsh Countryside (London, 1975), Egryn dated back to the fifteenth century. But its founda- tions were dated in David Williams’s Atlas of Cistercian Lands in Wales (Cardiff, 1990) as early as 1391. In the eighteenth century, the house had been something of a centre of culture in Meirionnydd where ‘the sound of harp music and interludes were played’, with ‘the drinking of mead and the singing of ancient song’, according to the scholar William Owen-Pughe who lived there. Owen- Pughe’s name in his time was among the most famous in Welsh culture. An important lexicographer, his dictionary left its influence heavily, even notoriously, on the development of nineteenth-century literature. And it is strangely coincidental that in the twentieth century, in his home, was born and bred for a while a major Welsh literary scholar, superior to him by far in his achievement, who too, for his first professional activity, had started his career as a lexicographer. -

Everyone Can Help! Found Signs of a Stowaway?

PROTECT OUR ISLANDS FROM NON-NATIVE PREDATORS Martin’s Haven is the gateway to the spectacular seabird islands of Skomer, Skokholm, Middleholm and Grassholm. Everyone can help! During the breeding season Skomer, Skokholm and Middleholm hold HOW DO NON-NATIVE SPECIES internationally important populations of seabirds including puffin, storm petrel REACH OUR ISLANDS? and nearly half a million breeding pairs of Manx Shearwaters. These birds nest Are you travelling to, between or around islands? in burrows or crevices to protect them from avian predators. Grassholm is also Make sure you don’t take any stowaways with you! of global significance for its seabirds and is the only Northern Gannet colony in Wales. It is so jam packed with gannets that the island appears white from a CHECK YOUR BOAT distance. If non-native land predators, like rats, were to reach our islands they would decimate bird populations. Please help us to keep our seabirds safe. CHECK YOUR CARGO CHECK YOUR BAGGAGE Vulnerable species include: Found signs of a stowaway? ATLANTIC EUROPEAN NORTHERN MANX PUFFIN STORM-PETREL GANNET SHEARWATERS Dangerous non-native predators include: DROPPINGS GNAW ENTRANCE NESTING MARKS HOLES MATERIAL DON’T TRAVEL TO AN ISLAND DON’T THROW OVERBOARD RAT MOUSE MINK HEDGEHOG FUNDED BY A PARTNERSHIP WITH ADDITIONAL FUNDING FROM: Thank you for helping to protect our native island wildlife! NatureScot, Natural England, Natural Resources Wales, and Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (Northern Ireland) Find out more at biosecurityforlife.org.uk. -

Introduction

introduction The Pembrokeshire Coast National 10 Park has some of the most unspoilt 11 seals and spectacular coastal scenery Goodwick in the UK. It is an area rich in Fishguard We are very fortunate to share our waters with grey seals. They wildlife and is designated as being are sensitive to disturbance and are protected by law. They haul internationally and nationally out to pup on the Pembrokeshire coastline and offshore islands important for marine habitats usually from August to the end of November.Although there may be and species. 9 4 gatherings of large groups at any time of year. St. Davids seabirds The maps and codes of conduct 1. Do not land on pupping beaches from 1st August to the end of November The 1st March to the 31st July is a particularly sensitive time as in this leaflet highlight the existing Bishops and do not disturb mothers nursing pups. Adult females often rest about & Clerks birds come ashore to nest. Sensitive sites include steep cliffs and Ramsey 10-30m away from the shore and their pup. Avoid coming between them. Agreed Access Restrictions Island zawns. The Pembrokeshire coastline and offshore islands have St. Bride’s 2. Avoid creeping up on seals or approaching them bow on. They may that have been drawn up by Bay nationally and internationally important populations of seabirds. Haverfordwest perceive you as a predator. conservation experts and coastal Skomer Island 6 Narberth 6 3. Keep your distance and keep at least 20m away from seals unless they 1. Plan trips carefully and with respect to users. -

The Thirteenth Mt Haemus Lecture

THE ORDER OF BARDS OVATES & DRUIDS MOUNT HAEMUS LECTURE FOR THE YEAR 2012 The Thirteenth Mt Haemus Lecture Magical Transformation in the Book of Taliesin and the Spoils of Annwn by Kristoffer Hughes Abstract The central theme within the OBOD Bardic grade expresses the transformation mystery present in the tale of Gwion Bach, who by degrees of elemental initiations and assimilation becomes he with the radiant brow – Taliesin. A further body of work exists in the form of Peniarth Manuscript Number 2, designated as ‘The Book of Taliesin’, inter-textual references within this material connects it to a vast body of work including the ‘Hanes Taliesin’ (the story of the birth of Taliesin) and the Four Branches of the Mabinogi which gives credence to the premise that magical transformation permeates the British/Welsh mythological sagas. This paper will focus on elements of magical transformation in the Book of Taliesin’s most famed mystical poem, ‘The Preideu Annwfyn (The Spoils of Annwn), and its pertinence to modern Druidic practise, to bridge the gulf between academia and the visionary, and to demonstrate the storehouse of wisdom accessible within the Taliesin material. Introduction It is the intention of this paper to examine the magical transformation properties present in the Book of Taliesin and the Preideu Annwfn. By the term ‘Magical Transformation’ I refer to the preternatural accounts of change initiated by magical means that are present within the Taliesin material and pertinent to modern practise and the assumption of various states of being. The transformative qualities of the Hanes Taliesin material is familiar to students of the OBOD, but I suggest that further material can be utilised to enhance the spiritual connection of the student to the source material of the OBOD and other Druidic systems. -

Mabinogion Mélodrame Gallois, Pour Quatuor À Cordes Et Voix

DOSSIER D’ACCOMPAGNEMENT Mabinogion Mélodrame gallois, pour quatuor à cordes et voix Quatuor Béla, Elise Caron Ma 13 déc 14:30 / me 14 déc 19:30 je 15 déc 14:30 Théâtre Charles Dullin Espace Malraux scène nationale de Chambéry et de la Savoie Espace Malraux scène nationale de Chambéry et de la Savoie – Saison 2016-2017 Mabinogion Durée 1h01 Chant, récit Elise Caron, violons Julien Dieudegard, Frédéric Aurier, alto Julian Boutin, violoncelle Luc Dedreuil, texte Arthur Lestrange, composition Frédéric Aurier, sonorisation Emile Martin production L’Oreille Droite / Quatuor Béla coproduction Espace Malraux scène nationale de Chambéry et de la Savoie, le Festival d’Ile de France Espace Malraux scène nationale de Chambéry et de la Savoie – Saison 2016-2017 Mabinogion Le spectacle Les Manibogion ou Les quatre Branches du Manibogion sont une série de quatre contes dont on trouve la trace dans deux manuscrits, rédigés en langue galloise au quatorzième siècle. Leur origine est sans doute bien plus ancienne encore que cela. Ces histoires faisaient partie du corpus de légendes que les bardes médiévaux (car la fonction de barde s’est conservée très longtemps au pays de Galles), poètes de cour et détenteurs officiels de la tradition se devaient d’avoir à leur répertoire. On trouve dans ces récits les traces et le parfum de personnages mythologiques, de divinités des anciens celtes, peut-être même de grands archétypes indo- européens. Tombés petit à petit dans l’oubli, il faudra attendre le XIXème siècle pour que des érudits passionnés comme Lady Charlotte Guest, redonnent une vie à ces histories et les traduisent en anglais. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it. -

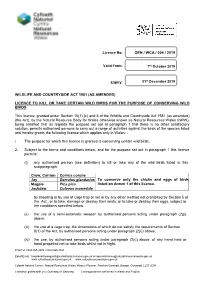

Licence to Kill Or Take Certain Wild Birds for the Purpose of Conserving Wild Birds

Licence No: GEN / WCA / 004 / 2019 Valid From: th 7 October 2019 Expiry: 31st December 2019 WILDLIFE AND COUNTRYSIDE ACT 1981 (AS AMENDED) LICENCE TO KILL OR TAKE CERTAIN WILD BIRDS FOR THE PURPOSE OF CONSERVING WILD BIRDS This licence, granted under Section 16(1) (c) and 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (as amended) (the Act), by the Natural Resource Body for Wales otherwise known as Natural Resources Wales (NRW), being satisfied that as regards the purpose set out at paragraph 1 that there is no other satisfactory solution, permits authorised persons to carry out a range of activities against the birds of the species listed and hereby grants the following licence which applies only in Wales: - 1. The purpose for which this licence is granted is conserving certain wild birds. 2. Subject to the terms and conditions below, and for the purpose set out in paragraph 1 this licence permits: (i) any authorised person (see definition) to kill or take any of the wild birds listed in this subparagraph Crow, Carrion Corvus corone Jay Garrulus glandarius To conserve only the chicks and eggs of birds Magpie Pica pica listed on Annex 1 of this licence. Jackdaw Coloeus monedula by shooting or by use of cage trap or net or by any other method not prohibited by Section 5 of the Act ; or to take, damage or destroy their nests; or to take or destroy their eggs, subject to the conditions specified below. (ii) the use of a semi-automatic weapon by authorised persons acting under paragraph (2)(i) above; (iii) the use of a cage trap, the dimensions of which do not satisfy the requirements of Section 8(1) of the Act, by authorised persons acting under paragraph (2)(i) above; (iv) the use, by authorised persons acting under paragraph (2)(i) above, of any hand held or hand propelled net to take birds whilst not in flight.