Indian Law for Local Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 225/Tuesday, November 21, 2000

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 225 / Tuesday, November 21, 2000 / Notices 69963 Mohican Indians of Wisconsin, the Band of Mohawk Indians of New York, Dated: November 14, 2000. Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians of the Stockbridge-Munsee Community of John Robbins, New York, and the Tuscarora Nation of Mohican Indians of Wisconsin, the Assistant Director, Cultural Resources New York. Representatives of any other Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians of Stewardship and Partnerships. Indian tribe that believes itself to be New York, and the Tuscarora Nation of [FR Doc. 00±29810 Filed 11±20±00; 8:45 am] culturally affiliated with these human New York. BILLING CODE 4310±70±F remains and associated funerary objects In 1961±1962, partial human remains should contact Connie Bodner, NAGPRA Liaison, Rochester Museum representing 25 individuals were DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR and Science Center, 657 East Avenue, recovered from the Pen site (Tly 003) in Rochester, NY 14607±2177, telephone Lafayette, Onondaga County, NY, by National Park Service (716) 271±4552, extension 345, before Peter Pratt and other unnamed Notice of Inventory Completion for December 21, 2000. Repatriation of the individuals. These were donated to the Rochester Museum and Science Center Native American Human Remains and human remains to the St. Regis Band of Associated Funerary Objects in the Mohawk Indians of New York may in 1979. No known individuals were identified. No associated funerary Possession of the Rochester Museum begin after that date if no additional and Science Center, Rochester, NY claimants come forward. objects are present. Dated: November 14, 2000. Based on skeletal morphology, these AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Federal Register/Vol. 80, No. 23/Wednesday, February 4, 2015

6120 Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 23 / Wednesday, February 4, 2015 / Notices determined they are of Native American Indian Tribe of Oklahoma, subject to Liaison, History Colorado, 1200 ancestry. No known individuals were forthcoming conditions imposed by the Broadway, Denver, CO 80203, telephone identified. No associated funerary Secretary of the Interior. On May 15–16, (303) 866–4531, email sheila.goff@ objects are present. 2008, the responses from the Jicarilla state.co.us by March 6, 2015. After that In May 2014, human remains Apache Nation, New Mexico, and the date, if no additional requestors have representing, at minimum, one Kiowa Indian Tribe of Oklahoma were come forward, transfer of control of the individual were inadvertently submitted to the Review Committee. On human remains to the Southern Ute discovered at the bottom of a slope on September 23, 2008, the Assistant Indian Tribe of the Southern Ute private property near Grand Mesa, CO. Secretary for Fish and Wildlife and Reservation, Colorado, and the Ute The Mesa County Coroner investigated Parks, as the designee for the Secretary Mountain Tribe of the Ute Mountain and ruled out forensic interest. The of the Interior, transmitted the Reservation, Colorado, New Mexico & exact location from which the human authorization for the disposition of Utah may proceed. remains originated could not be located, culturally unidentifiable human History Colorado is responsible for but it is presumed they eroded from remains according to the Process and notifying The Consulted and Invited higher ground. The human remains NAGPRA, pending publication of a Tribes that this notice has been were transferred to History Colorado, Notice of Inventory Completion in the published. -

Ogden Land Company

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 2-25-1897 Ogden Land Company. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation S. Doc. No. 154, 54th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1897) This Senate Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 54TH CONGRESS,} SENATB. DocuMENT 2r7 Sess·ion. { No. 154. OGDEN LA~D COMPANY. FEBRUARY 25, 1897.-Laid on the table and ordered to be printed. Mr. O.A.LL presented the following MEMORIAL OF THE SENECA NATION OF INDIANS, PROTESTING AGAINST THE PROPOSED PURCHASE BY THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR OF THE TITLE OR INTEREST OF THE OGDEN LAND COMPANY, SO CALLED, IN' AND TO THE LANDS EMBRACED WITHIN THE AI,LEGANY AND CATTARAUGUS INDIAN RESER VATIONS, IN THE S 'TATE OF NEW YORK. EXECUTIVE DEP.A.RTMENT, SENECA N A'l'ION OF INDIANS, Salamanca,, N. Y., -----, 1897. Know all men by these presents: That the Seneca Nation of Indians in council assembled have duly made and appointed W. C. Hoag, A. L. Jimerson, Frank Patterson, W. W. Jimerson, and W. S. Kennedy to be our delegates to go to Washington, D. -

In the Recent Dear Colleague Letter 99-30, OCSE Notified You of A

Location Codes Workgroup FIPS Coding Scheme Recommendation Summary Position 1 Position 2 Positions 3-5 Interstate Case FIPS State Identifier County/Functional Entity 9 0 BIA Tribe Identifier Tribal Case (Federally recognized) 8 0 ISO Country Identifier International Case Exception 0-9, A-Z (Canada – sub- jurisdiction) Tribal and International Case Location Codes 1 OCSE Case Locator Code Data Standards Tribal locator codes coding scheme Tribal Case Locator Codes • Classification code - 9 in position 1 • “0”(zero) in position 2 • Tribe Identification - BIA code in positions 3-5 Example: Chickasaw Nation 90906 • Addresses for tribal grantees– provided by tribes to IRG staff List of current tribal grantees: http://ocse.acf.hhs.gov/int/directories/index.cfm?fuseaction=main.tribalivd • Link to tribal government addresses web site: http://www.doi.gov/leaders.pdf 11/15/2006 2 OCSE Case Locator Code Data Standards Tribal Identification Codes Code Name 001 Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians of North Carolina 006 Onondaga Nation of New York 007 St. Regis Band of Mohawk Indians of New York 008 Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians of New York 009 Tuscarora Nation of New York 011 Oneida Nation of New York 012 Seneca Nation of New York 013 Cayuga Nation of New York 014 Passamaquoddy Tribe of Maine 018 Penobscot Tribe of Maine 019 Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians of Maine 020 Mashantucket Pequot Tribe of Connecticut 021 Seminole Tribe of Florida, Dania, Big Cypress, Brighton, Hollywood & Tampa Reservations 026 Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida 027 Narragansett -

Notice of Intent to Repatriate Cultural Items: New York State Museum

74866 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 243 / Tuesday, December 18, 2012 / Notices connecting the two substations, an comments resulted in the addition of History and Description of the Cultural electrical interconnection facility/ clarifying text, but did not significantly Items switchyard owned and operated by change the proposed alternatives. The cultural items are eight wampum Western, an operations and belts. Seven of the wampum belts are on maintenance building, and temporary Vanessa Hice, Assistant Field Manager, Division of Lands. loan to the Seneca National Museum in and long-term laydown areas. Three Salamanca, NY, and one wampum belt meteorological towers would remain on Authority: 40 CFR 1506.6, 40 CFR 1506.10. is housed at the New York State the site to measure the wind speed and [FR Doc. 2012–30537 Filed 12–14–12; 4:15 pm] Museum in Albany, NY. direction across the site over the life of BILLING CODE 4310–HC–P The Five Nations Alliance Belt, also the project. known as the Mary Jamison Belt, is The applicant (SWE) has requested to composed of seven rows of dark purple interconnect its proposed project to the DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR beads with three open white diamonds. electrical transmission grid via The belt measures 161⁄4 inches long and Western’s Davis-Mead 230-kilovolt National Park Service two inches wide. It is a portion of an transmission line. Western, a Federal original belt that measured two feet long agency, is participating in the EIS [NPS–WASO–NAGPRA–11793; 2200–1100– and contained five diamonds process as a cooperating agency and 665] representing the Five Iroquois Nations. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 27/Friday, February 8, 2019/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 27 / Friday, February 8, 2019 / Notices 2911 Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, University on April 18, 1874. The The Invited Tribes that this notice has Michigan and Indiana; Saginaw human remains are grouped together been published. Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan, and thus cannot be linked to any of the Dated: December 11, 2018. and the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of specific three locations listed as the Melanie O’Brien, Chippewa Indians, Michigan, hereafter sources. Analysis of the human remains Manager, National NAGPRA Program. referred to as ‘‘The Consulted Tribes.’’ suggests that between twelve and Additional invitations to consult were eighteen individuals are represented. [FR Doc. 2019–01610 Filed 2–7–19; 8:45 am] sent to the Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Sex cannot be determined due to the BILLING CODE 4312–52–P Indians of Oklahoma; Bad River Band of lack of pelves or intact crania. At least the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa one individual was in early childhood DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Indians of the Bad River Reservation, (from 2–6 years old), at least one was an Wisconsin; Chippewa Cree Indians of adolescent (from 16–21 years old), and National Park Service the Rocky Boy’s Reservation, Montana the remainder were adults. No known (previously listed as the Chippewa-Cree individuals were identified. No [NPS–WASO–NAGPRA–NPS0027191; Indians of the Rocky Boy’s Reservation, associated funerary objects are present. PPWOCRADN0–PCU00RP14.R50000] Montana); Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Oklahoma; Delaware Nation, Oklahoma; Determinations Made by Princeton Notice of Intent To Repatriate Cultural Delaware Tribe of Indians; Eastern University Items: U.S. -

Table-12.Pdf

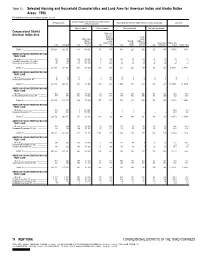

Table 12. Selected Housing and Household Characteristics and Land Area for American Indian and Alaska Native Areas: 1990 [For definitions of terms and meanings of symbols, see text] Occupied housing units with American Indian, Eskimo, All housing units or Aleut householder Households with American Indian, Eskimo, or Aleut householder Land area Owner occupied Renter occupied Family households Nonfamily households Congressional District Mean con- American Indian Area tract rent (dollars), Female Mean value specified house- (dollars), renter Married- holder, no specified paying cash couple husband Householder Square kilo- Total Occupied Total owner Total rent Total family present Total living alone meters Square miles ------------------------ District 1 239 124 192 807 313 139 800 176 637 364 224 109 125 105 1 650.6 637.3 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 219 180 139 95 800 13 400 108 72 24 44 44 3.6 1.4 Poospatuck Reservation, NY (state)-------- 46 45 29 175 200 2 313 23 13 6 8 8 .2 .1 Shinnecock Reservation, NY (state)-------- 173 135 110 86 100 11 458 85 59 18 36 36 3.4 1.3 ----------------------- District 23 243 283 211 591 264 63 700 234 286 331 228 77 167 128 15 504.1 5 986.1 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 20 1211–1363104421.2.1 Oneida (East) Reservation, NY------------ 20 1211–1363104421.2.1 ----------------------- District 24 261 036 202 380 934 46 900 489 264 1 055 734 234 368 291 32 097.8 12 393.0 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 754 634 561 45 000 64 184 485 342 106 140 124 49.2 19.0 St. -

Niagara Falls National Heritage Area Commission

Niagara Falls National Heritage Area Part II – Management Plan Niagara Falls National Heritage Area Commission July 2012 NIAGARA FALLS NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA Part II - Management Plan Submitted to: The Niagara Falls National Heritage Area Commission U.S. National Park Service and Ken Salazar U.S. Secretary of the Interior Consulting team: John Milner Associates, Inc. Heritage Strategies, LLC National Trust for Historic Preservation Bergmann Associates July 2012 NIAGARA FALLS NATIONAL HERITAGE A REA MANAGEMENT PLAN Part II – Implementation Plan ii NIAGARA FALLS NATIONAL HERITAGE A REA MANAGEMENT PLAN Table of Contents PART II ─ MANAGEMENT PLAN CHAPTER 1 ─ CONCEPT AND APPROACH 1.1 What is a National Heritage Area? ................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Designation of the Niagara Falls National Heritage Area ................................ 1-2 1.3 Vision, Mission, and Goals of the National Heritage Area .............................. 1-3 1.4 The Heritage Area’s Preferred Alternative ....................................................... 1-4 1.5 National Signifi cance of the Heritage Area ......................................................1-6 1.6 The National Heritage Area Concept ............................................................... 1-8 1.6.1 Guiding Principles................................................................................... 1-8 1.6.2 Using the Management Plan ................................................................... 1-9 1.6.3 Terminology ............................................................................................1-9 -

![[Nps-Waso-Nagpra-Nps0032391; Ppwocradn0-Pcu00rp14.R50000]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0941/nps-waso-nagpra-nps0032391-ppwocradn0-pcu00rp14-r50000-1720941.webp)

[Nps-Waso-Nagpra-Nps0032391; Ppwocradn0-Pcu00rp14.R50000]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 08/11/2021 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2021-17065, and on govinfo.gov 4312-52 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service [NPS-WASO-NAGPRA-NPS0032391; PPWOCRADN0-PCU00RP14.R50000] Notice of Inventory Completion: New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation, Waterford, NY AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation (NYSOPRHP) has completed an inventory of human remains, in consultation with the appropriate Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian organizations, and has determined that there is a cultural affiliation between the human remains and present-day Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian organizations. Lineal descendants or representatives of any Indian Tribe or Native Hawaiian organization not identified in this notice that wish to request transfer of control of these human remains should submit a written request to the NYSOPRHP. If no additional requestors come forward, transfer of control of the human remains to the lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, or Native Hawaiian organizations stated in this notice may proceed. DATES: Lineal descendants or representatives of any Indian Tribe or Native Hawaiian organization not identified in this notice that wish to request transfer of control of these human remains should submit a written request with information in support of the request to the NYSOPRHP at the address in this notice by [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Andrew Farry (Scientist/Archaeology), Division for Historic Preservation, P.O. -

Federal Register/Vol. 82, No. 170/Tuesday

41984 Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 170 / Tuesday, September 5, 2017 / Notices human cranial bone, which was Between A.D. 1450 and 1600, diagnostic 2017. After that date, if no additional contained together with the dentition in characteristics indicative of the Seneca requestors have come forward, transfer a display case. culture begin to become evident in the of control of the human remains and On an unknown date, human remains archeological record. Seneca occupation associated funerary object to the Seneca consisting of 22 loose teeth, of Ontario County, NY, is well- Nation of Indians (previously listed as representing, at minimum, 5 individuals documented. From the early 16th the Seneca Nation of New York); (seizure-item number 817890–2) were century until the American Revolution, Seneca-Cayuga Nation (previously listed removed from an unknown location in the Seneca occupied a region between as the Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of the Finger Lakes region of New York, the Genesee River and Canandaigua Oklahoma); and Tonawanda Band of and more likely than not in Ontario Lake, which includes Livingston and Seneca (previously listed as the County, NY. Adults and children of Ontario Counties, NY, as well as the Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians of both sexes are represented. The age of southern portion of Monroe County, NY. New York) may proceed. one child is 9 or 10 years. Five teeth, Today, the Seneca are represented by The USFWS OLE is responsible for which represent two individuals, have three federally recognized Indian Tribes: notifying the Cayuga Nation; Oneida green copper oxide staining. This type The Seneca Nation of Indians Nation (previously listed as the Oneida of staining is often seen in Protohistoric (previously listed as the Seneca Nation Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin); Oneida and historic burials.