Need Brodock Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Newsletter for Columbus Audubon Programming

Delaware County Bird Club NEWSLETTER Vol. 35 No. 7 Delaware County Bird Club Newsletter March 2021 DELAWARE COUNTY BIRD brood parasitism of Brown-headed Cowbirds (Molothrus CLUB PROGRAMS ater) on Least Bell’s Vireos (Vireo bellii pusillus). Bryan also holds a Master’s in Educational For the Winter of 2021, the DCBC will continue Administration and has been a teacher or principal for 19 going virtual - Zoom meetings instead of in-person years. Other jobs he has held include banding birds of programs. We will hold them in the same time slot - on prey for a season in the Florida Keys, being a summer the fourth Monday of each month at 7:00 PM. If you camp counselor in North Carolina and Colorado, would be interested in joining such Zoom meetings, conducting point counts of birds in a riparian restoration please send an email message to Rich Bradley from the area, sequencing avian DNA and as a Park Ranger and account you would use for the Zoom registration. Your later a Naturalist with Franklin County Metro Parks in email will then be added to a list for use in sending Columbus, Ohio. He has also volunteered as an ecology Zoom links about the meetings. Please send your sign-up and bird guide at parks in San Diego, CA and Durango, message to Rich Bradley at his alternate email Mexico where he lived for five and 11 years, address under the name Alan Bradley respectively. He is the compiler of the Christmas Bird ([email protected]). Count for the latter city. -

Gear for a Big Year

APPENDIX 1 GEAR FOR A BIG YEAR 40-liter REI Vagabond Tour 40 Two passports Travel Pack Wallet Tumi luggage tag Two notebooks Leica 10x42 Ultravid HD-Plus Two Sharpie pens binoculars Oakley sunglasses Leica 65 mm Televid spotting scope with tripod Fossil watch Leica V-Lux camera Asics GEL-Enduro 7 trail running shoes GoPro Hero3 video camera with selfie stick Four Mountain Hardwear Wicked Lite short-sleeved T-shirts 11” MacBook Air laptop Columbia Sportswear rain shell iPhone 6 (and iPhone 4) with an international phone plan Marmot down jacket iPod nano and headphones Two pairs of ExOfficio field pants SureFire Fury LED flashlight Three pairs of ExOfficio Give- with rechargeable batteries N-Go boxer underwear Green laser pointer Two long-sleeved ExOfficio BugsAway insect-repelling Yalumi LED headlamp shirts with sun protection Sea to Summit silk sleeping bag Two pairs of SmartWool socks liner Two pairs of cotton Balega socks Set of adapter plugs for the world Birding Without Borders_F.indd 264 7/14/17 10:49 AM Gear for a Big Year • 265 Wildy Adventure anti-leech Antimalarial pills socks First-aid kit Two bandanas Assorted toiletries (comb, Plain black baseball cap lip balm, eye drops, toenail clippers, tweezers, toothbrush, REI Campware spoon toothpaste, floss, aspirin, Israeli water-purification tablets Imodium, sunscreen) Birding Without Borders_F.indd 265 7/14/17 10:49 AM APPENDIX 2 BIG YEAR SNAPSHOT New Unique per per % % Country Days Total New Unique Day Day New Unique Antarctica / Falklands 8 54 54 30 7 4 100% 56% Argentina 12 435 -

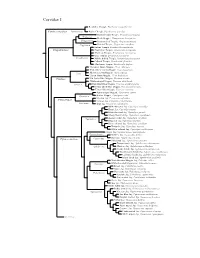

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

The White-Throated Magpie-Jay

THE WHITE-THROATED MAGPIE-JAY BY ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH ORE than 15 years have passed since I was last in the haunts of the M White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa) . During the years when I travelled more widely through Central America I saw much of this bird, and learned enough of its habits to convince me that it would well repay a thorough study. Since it now appears unlikely that I shall make this study myself, I wish to put on record such information as I gleaned, in the hope that these fragmentary notes will stimulate some other bird- watcher to give this jay the attention it deserves. A big, long-tailed bird about 20 inches in length, with blue and white plumage and a high, loosely waving crest of recurved black feathers, the White-throated Magpie-Jay is a handsome species unlikely to be confused with any other member of the family. Its upper parts, including the wings and most of the tail, are blue or blue-gray with a tinge of lavender. The sides of the head and all the under plumage are white, and the outer feathers of the strongly graduated tail are white on the terminal half. A narrow black collar crosses the breast and extends half-way up each side of the neck, between the white and the blue. The stout bill and the legs and feet are black. The sexes are alike in appearance. The species extends from the Mexican states of Colima and Puebla to northwestern Costa Rica. A bird of the drier regions, it is found chiefly along the Pacific coast from Mexico southward as far as the Gulf of Nicoya in Costa Rica. -

Avian Survey Report

Spring/Summer 2010 Avian Survey Report Stony Creek Wind Farm Wyoming County, New York January 24, 2011 PREPARED FOR: Stony Creek Energy LLC 51 Monroe St. Suite 1604 Rockville, MD 20850 PREPARED BY: Lackawanna Executive Park 239 Main Street, Suite 301 Dickson City, PA 18519 www.shoenerenvironmental.com Stony Creek Wind Farm Avian Survey January 24, 2011 Table of Contents I. Summary and Background .................................................................................................1 Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Project Description ........................................................................................................1 Project Review Background ..........................................................................................2 II. Bald Eagle Survey .............................................................................................................3 Bald Eagle Breeding Status in New York ......................................................................3 Daily Movements of Bald Eagle in New York ...............................................................4 Bald Eagle Conservation Status in New York ................................................................4 Bald Eagle Survey Method ............................................................................................5 Analysis of Bald Eagle Survey Data ..............................................................................6 -

Western Mexico

Cotinga 14 W estern Mexico: a significant centre of avian endem ism and challenge for conservation action A. Townsend Peterson and Adolfo G. Navarro-Sigüenza Cotinga 14 (2000): 42–46 El endemismo de aves en México está concentrado en el oeste del país, pues entre el 40 al 47% de las aves endémicas de México están totalmente restringidas a la región. Presentamos un compendio de estos taxones, tanto siguiendo el concepto biológico de especie como el concepto filogenético de especie, documentando la región como un importante centro de endemismo. Discutimos estrategias de conservación en la región, especialmente la idea de ligar reservas para preservar transectos altitudinales de hábitats continuos, desde las tierras bajas hasta las mayores altitudes, en áreas críticas. Introduction and Transvolcanic Belt of central and western Mexico has been identified as a megadiverse coun Mexico were identified as major concentrations of try, with impressive diversity in many taxonomic endemic species. This non-coincidence of diversity groups20. Efforts to document the country’s biologi and endemism in Mexican biodiversity has since cal diversity are at varying stages of development been documented on different spatial scales13,17 and in different taxa17,19,20 but avian studies have ben in additional taxonomic groups17. efited from extensive data already accumulated18 In prior examinations, however, western Mexico and have been able to advance to more detailed lev (herein defined as the region from Sonora and Chi els of analysis6,12,17. huahua south to Oaxaca, including the coastal In the only recent countrywide survey of avian lowlands, the Sierra Madre Occidental and Sierra diversity and endemism6, the south-east lowlands Madre del Sur, and Pacific-draining interior basins were identified as important foci of avian species such as the Balsas Basin) has not been appreciated richness. -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania. -

A Taxonomic Revision of the New World Jays

A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE NEW WORLD JAYS JOHN WILLIAM HARDY Moore Laboratory of Zoology Occidental College Los Angeles, California 90041 The generic and sub-generic classification of list of North American birds (including Mex- the New World jays employed by Blake (in ice and Central America), I feel it necessary Mayr and Greenway X%2:266-228) perpetu- to state my views formally on the taxonomy ates a system largely similar to that of the of New World jays, even though the habits of earliest authoritative works on New World many species in the assemblage are still poorly birds (e.g., Sharpe 1877). Blake does sub- known. merge Uroleuca Temminck and Xanthoura The following annotated arrangement ex- Nelson, which were still recognized by Hell- cludes’ the genera Gymnorhinus and Perisoreus, mayr (1934:29,30) but does not follow recom- which I do not consider to be a part of the mendations for mass lumping of genera pro- New World assemblage otherwise considered posed by Amadon ( 1944a). Phillips et al. here. The former contains only one species, (1964:106) have since also recommended which is not a jay at all by any standard except large scale amalgamation of genera in this that its plumage is blue in color. It is probably assemblage. Amadons’ recommendations were derived from Old World corvines such as premature; information on these jays gathered Nucifraga (Hardy 1961:113) which it re- and published during the past two decades sembles, except in color. Perisoreus consists of has negated some of his conclusions. Phillips two Asiatic species, one (infaustus) wide- et al. -

The Azure Jay May Reproduce in Plantations of Araucaria Angustifolia in Southern Brazil

Bird Conservation International (2012) 22:205–212. © BirdLife International, 2012 doi:10.1017/S0959270911000529 The Azure Jay may reproduce in plantations of Araucaria angustifolia in southern Brazil ANDREA LARISSA BOESING and LUIZ DOS ANJOS Summary We undertook field observations of the Azure Jay Cyanocorax caeruleus in Araucaria plantations and a secondary forest in southern Brazil from 2007 to 2010. During the breeding season, the territory and the flock sizes in Araucaria plantations (31.6–42.2 ha; 2–3 individuals) seemed to be smaller than in the secondary forest (64.5–72.6 ha; 5–6 individuals). One active nest was monitored in October–November 2009 and indicated cooperative breeding by the Azure Jay, as for the majority of American jays. The fact that reproduction was documented in Araucaria plantations may be positive for the conservation of this species, since natural areas of mixed rainforest are becoming increasingly scarce. Introduction The Azure Jay Cyanocorax caeruleus is the most endangered of the South American species in the Cyanocorax genus, and is classified as ‘Near Threatened’ (BirdLife International 2008). Field observations have suggested that this species is undergoing a substantial decline in numbers, particularly in western areas of its range, where mixed rainforest (a type of southern temperate forest) occurs (Ridgely and Tudor 1989, Stotz et al. 1996, BirdLife International 2000). The Azure Jay population decline is probably caused by the fragmentation and degradation of this forest type (Anjos 1991). The conifer Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze is classified as ‘Critically Endangered’ (IUCN 2010) and comprises around 40% of the trees in mixed rainforest, with the result that the canopy is almost exclusively composed of this species (Schäffer and Prochnow 2002). -

Status and Conservation of Old-Growth Forests and Endemic Birds in the Pine-Oak Zone of the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico

VERSLAGEN EN TECHNISCHE GEGEVENS Institute for Systematics and Population Biology (Zoological Museum) University of Amsterdam P.O. Box 94766, 1090 GT Amsterdam The Netherlands No. 69, October 1996 Status and conservation of old-growth forests and endemic birds in the pine-oak zone of the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico J.M. Lammertink J.A. Rojas-Tome F.M. Casillas-Orona and R.L. Otto ISSN 1385-3279 Status and conservation of old-growth forests and endemic birds in the pine-oak zone of the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico Estatus y conservacion de los bosques maduros y las aves endemicas en la zona de pino-encino de Ia Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico by J.M. Lammertink, J.A. Rojas-Tome, F.M. Casillas-Orona and R.L. Otto cartography: Hubert Kivit photography: Martjan Lammertink addresses: Martjan Lammertink Institute for Systematics and Population Biology P.O. Box 94766 1090 GT Amsterdam, The Netherlands fax:(## 31) 20 525 7238 e-mail: [email protected] Jorge Rojas-Tome Departamento de Zoologia Instituto de Biologia UNAM Apartado Postal 70-153 04510 Mexico D.F. Del. Coyoacan, Mexico fax:(## 52) 5 550 0164 e-mail: [email protected] Federico Casillas-Orona SEMARNAP Durango Calle Pasteur 620 nte 34000 Durango, Durango, Mexico fax(## 52) 18 12 72 26 Roger Otto Calle Tecnologico 205-1 Col. Olga Margarita 34000 Durango, Durango, Mexico tel. (##52) 18 176924 or: 420 E-main Pierce, Nebraska 68767 USA © Institute for Systematics and Population Biology University of Amsterdam P.O. Box 94766 1090 GT Amsterdam, The Netherlands ISSN 1385-3279 Table of contents Summary..................................................................................... -

Vocal Repertoire and Its Possible Evolution in the Black and Blue Jays (Cissilopha)

WilsonBull., 91(Z), 1979, pp. 187-201 VOCAL REPERTOIRE AND ITS POSSIBLE EVOLUTION IN THE BLACK AND BLUE JAYS (CZSSZLOPHA) JOHN WILLIAM HARDY The 4 allopatric Middle American jays of the taxon Cissilopha, which I treat as a subgenus of Cyanocorax (Hardy 1969)) are communally social year round (Hardy 1976, Raitt and Hardy 1976). The species are the Yucatan Jay (C. yucatanica), Bushy-crested Jay (C. melanocyanea), San Blas Jay (C. sanblasiana, with 2 distinct races, see Hardy and Raitt 1977)) and the Beechey Jay (C. beecheii) . Their displays as a group are distinctive although not very elaborate (Hardy 197433). Th eir vocal repertoires superficially seem small, as short-term experiences in the wild usually allow the observer to hear only 1 or 2 call types and these mainly from excited groups. Each form has a more extensive vocabulary. In this paper I describe the known vocalizations, assign them to behavioral or motivational contexts, show some context patterns in tabular form, and speculate on the possible nature of evolution of vocabulary in the group. As described in detail elsewhere (Hardy 1973, 1974a, b, 1976; Raitt and Hardy 1976) all these jays were studied in the wild and in captivity. Recordings were analyzed on a Kay Electric Company Sona-Graph, Model 7029A, for sonograms (all wide band) pre- sented here. All recordings or exact copies of them are deposited in the Bioacoustic Archive of the Florida State Museums’ Department of Natural Sciences. The 4 tables showing context and pattern of vocalizations are based entirely upon tape recorded sequences in the Archive.