Nebraska Transit Corridors Study Commuter Rail and Express Bus Options Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 0 1 2 Annualreport

2012 ANNUAL REPORT RECHARGED Served at Retail SERVICE AREA MAP Served at Wholesale Elk City Station Power Station Valley Station Landfill-gas plant Wind Generation Wind Turbine 6.2 megawatts OPPD Headquarters .66 megawatts Elkhorn Ridge Wind Farm 25-megawatt participation agreement Fort Calhoun Station Crofton Bluffs Wind Farm Nuclear plant, 478.6 megawatts 13.6-megawatt participation North Omaha Station agreement Coal & natural-gas plant, 626.7 megawatts OPPD Headquarters Jones Street Station Oil plant, 122.7 megawatts Sarpy County Station Oil & natural-gas plant, 315.3 megawatts Cass County Station Natural-gas plant, 323.2 megawatts Ainsworth Wind Farm Nebraska City Station Unit 1 10-megawatt participation Coal plant, 651.5 megawatts agreement Nebraska City Station Unit 2 Petersburg Wind Farm Coal plant, 684.6 megawatts Broken Bow I Wind Farm 40.5-megawatt participation 18-megawatt participation agreement agreement Flat Water Wind Farm 60-megawatt participation About oppd agreement Omaha Public Power District is a publicly owned electric utility that serves a population of 780,455 people, more than any other electric utility in the state. Founded in 1946 as a public entity, the business-managed utility is governed by an elected board of eight directors. While its headquarters is located in Omaha, Neb., OPPD has several other locations in its 13-county, 5,000-square-mile service area in southeast Nebraska. The majority of OPPD’s power comes from three baseload power plants: North Omaha Station and Nebraska City Station, both coal-fired plants, and Fort Calhoun Station, a nuclear power plant. Additional energy comes from three peaking plants and renewable energy resources, including a landfill-gas plant and wind turbines. -

B-1 John W Barriger III Papers Finalwpref.Rtf

A Guide to the John W. Barriger III Papers in the John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library A Special Collection of the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri St. Louis This project was made possible by a generous grant From the National Historical Publications and Record Commission an agency of the National Archives and Records Administration and by the support of the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri St. Louis © 1997 The St. Louis Mercantile Library Association i Preface and Acknowledgements This finding aid represents the fruition of years of effort in arranging and describing the papers of John W. Barriger III, one of this century’s most distinguished railroad executives. It will serve the needs of scholars for many years to come, guiding them through an extraordinary body of papers documenting the world of railroading in the first two-thirds of this century across all of North America. In every endeavor, there are individuals for whom the scope of their involvement and the depth of their participation makes them a unique participant in events of historical importance. Such was the case with John Walker Barriger III (1899-1976), whose many significant roles in the American railroad industry over almost a half century from the 1920s into the 1970s not only made him one of this century’s most important railroad executives, but which also permitted him to participate in and witness at close hand the enormous changes which took place in railroading over the course of his career. For many men, simply to participate in the decisions and events such as were part of John Barriger’s life would have been enough. -

Historic Flood Contents

Historic Flood Contents On the cover: Fort Calhoun Nuclear Station 2 Safety First shown on June 15. Safety messaging was reinforced heavily as employees fought flooding. 3 Plan Springs from Year 2000 Work Although more than a decade apart, one year impacted the other in ways that no one at OPPD could have predicted. 5 Energized Workers Protect Power Plants 10 T&D and Substation Meet Challenges 13 Counting the Cost Tracking and categorizing OPPD’s flood-related costs in pursuit of FEMA reimbursement is a huge task. 14 Arming Employees to Fight the Flood When rising waters threatened OPPD facilities, a variety of supplies and equipment were brought in to help meet challenges. 16 The Little Dam That Could Gavins Point Dam served as a critical gate to help contain the floodwaters. Without the dam, it could have been much worse. 18 Flood Hardships Can’t Dampen Spirits Sense of family – and humor – bolster OPPD employees amid property loss, lengthy commutes and months of stress. Hey, Carl, let's blow this admin parking lot. 22 News of Flood Spread Across Globe OPPD communicators used many tools to disseminate information, I hear there's more to eat over at the squelch rumors and keep flood fighters on the same track. training center lot. : Vol. 91, No. 6, November/December 2011 Published bimonthly by the Corporate Commu- Contributing Staff Senior Management nications Division, Flash magazine provides OPPD DJ Clarke Chris Cobbs W. Gary Gates ........................................President employees and retirees with strategic industry- and Django Greenblatt-Seay Jeff Hanson Dave Bannister ................................Vice President job-related news, and human-interest articles about Sharon Jefferson Mike Jones Timothy J. -

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 33 • NUMBER 43 Saturday, March 2, 1968 • Washington, D.C

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 33 • NUMBER 43 Saturday, March 2, 1968 • Washington, D.C. Pages 4087-4130 Agencies in this issue— The President Agency for International Development Atomic Energy Commission Business and Defense Services Administration Civil Aeronautics Board Civil Service Commission Commodity Credit Corporation Consumer and Marketing Service Federal Aviation Administration Federal Communications Commission Federal Maritime Commission Federal Trade Commission Fish and Wildlife Service Food and Drug Administration Interior Department Internal Revenue Service Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau Packers and Stockyards Administration Securities and Exchange Commission Detailed list o f Contents appears inside. 2-year Compilation Presidential Documents Code of Federal Regulations TITLE 3, 1964-1965 COMPILATION Contains the full text of Presidential Proclamations, Executive orders, reorganization plans, and other formal documents issued by the President and published in the Federal Register during the period January 1,1964- December 31, 1965. Includes consolidated tabular finding aids and a consolidated index. Price: $3.75 Compiled by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 y a \ Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on Sundays, Mondays, or on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Register, National FEDERALJpEGISTER Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mall address National Area Code 202 A ® ^ Phonepi.«»- 962-8626oao_ ba9a Archives Building, Washington, D.O. 20408), pursuant to the authority contained in tbe Federal Register Act, approved July 26, 1935 (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.O., Ch. -

Students Driven to Succeed Contents

Students Driven to Succeed Contents On the cover: Hundreds of students, teachers, 2 Engineering Model parents and others have been Technical savvy and people skills define Tom Burton, the OPPD Soci- impacted by Power Drive. ety of Engineers’ Engineer of the Year. 4 FCS Receives CAL from NRC Serving as another milestone in the road to restart and recovery at Fort Calhoun Station, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued a 2 Confirmatory Action Letter to OPPD on June 11. 6 Driven to Success For 13 years, the Power Drive program has given students an outlet to showcase their ingenuity and creativity. 10 Rebuilding the Past In retirement, Dick Varner continues in his role as a caretaker for the land and structures of southeastern Nebraska. 12 Running Wild in Warrior Dash A group of OPPD employees were among the 20,000-plus individu- als who participated in Nebraska’s a first-ever Warrior Dash. 15 Graduate Section An impressive number of OPPD employees and their families made fashion statements in caps and gowns at commencement exercises 12 this summer. 23 People Anniversaries, retirements, deaths, sympathies and club notes. Back cover Flood of Memories The one-year anniversary of the Missouri River flood of 2011 served as a reminder of all the hard work by employees. : Vol. 92, No. 4, July/August 2012 Published bimonthly by the Corporate Commu- Contributing Staff Senior Management nications Division, Flash magazine provides OPPD DJ Clarke Paula Lukowski W. Gary Gates ........................................President employees and retirees with strategic industry- and Django Greenblatt-Seay Lisa Olson Dave Bannister ................................Vice President job-related news, and human-interest articles about Jeff Hanson Althea Pietsch Timothy J. -

2017 CSO Annual Report WORKING

Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................................................... I-5 II. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... II-7 A. Nine Minimum Controls (NMC) ................................................................................................................................ II-7 B. LTCP Documentation ............................................................................................................................................. II-10 C. Compliance Schedule ............................................................................................................................................ II-13 D. CSO Outfall Monitoring .......................................................................................................................................... II-14 E. In-stream Monitoring .............................................................................................................................................. II-14 F. Performance Report ............................................................................................................................................... II-14 G. Other Information ................................................................................................................................................... II-15 III. Nine Minimum Controls ......................................................................................... -

1 Last Stop Eau Claire: the Discontinuation of the Twin Cities

1 Last Stop Eau Claire: The Discontinuation of the Twin Cities 400 Matthew Bardwell History 489 Capstone Advisor—Robert Gough Cooperating Professor—James Oberly Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. 2 Abstract This paper will discuss the history of transportation in the United States from the national, state, and local view. This paper‟s primary focus is on the Twin Cities 400, a passenger train that ran through Eau Claire from Chicago on its way to Minneapolis. The paper will focus on the process of the discontinuation, the arguments from the city‟s point of view as well as the Chicago and North Western Railroad Company‟s point of view, and the ruling by the Interstate Commerce Commission on the proposed discontinuation. The paper will conclude talking about the possible future of passenger railroads in Eau Claire. 3 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………i I. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..1 II. History of Passenger Transportation in America…………………………………………5 III. History of Passenger Transportation in Wisconsin………………………………………10 IV. History of Passenger Transportation in Eau Claire………………………………………12 V. The Interstate Commerce Commission…………………………………………………..17 VI. The Discontinuation of the Twin Cities 400: Eau Claire‟s Opposition …………………21 VII. The Chicago and North Western Railroad Company‟s Position……………………….25 VIII. The Twin Cities 400 Discontinued………..…………………………………………....29 IX. Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….31 Appendixes A. Transportation Map of Wisconsin in 1962: Courtesy of Chicago and North Western Railway Company: Twin Cities 400 Records…………………………..............35 B. Summary of Average Daily Revenues and Expenses for the years 1959, 1960, and first 5 months of 1961: Courtesy of Chicago and North Western Railway Company: Twin Cities 400 Records………………………….............36 C. -

The US Access Board Complaints Database, 1976 - 2011

Description of document: The US Access Board complaints database, 1976 - 2011 Requested date: 01-May-2011 Released date: 10-May-2011 Posted date: 16-May-2011 Date/date range of document: 06-October-1976 – 29-April-2011 Source of document: FOIA Officer U.S. Access Board 1331 F Street NW, Suite 1000 Washington, DC 20004 Fax: 202-272-0081 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. From: "Fairhall, Lisa" <[email protected]> Date: Tue, 10 May 2011 10:01:55 -0400 Subject: Request under the Freedom of Information Act This is in response to your letter dated May 1, 2011, requesting certain Access Board documents under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). -

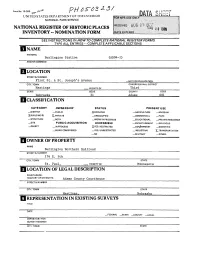

Lililiiiim^^ STREET ANCINUMBER: - *T 925 Sntrbf Lf)Th St.Rppt CITY OR TOWN:

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Nebraska COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Douglas INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) /iUfi 7 W4 lii;;!i;t!;^ COMMON: Thd Burlington Station AND/OR HISTORIC: HlililiiiiM^^ STREET ANCINUMBER: - *t 925 SntrBf lf)th St.rppt CITY OR TOWN: ....... CO NGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Omaha . Second- ST * TE CODE COLJ NTY: CO p-E Nebraska 31 Douglas 055 ;:^:::;::':::J!^:jfc:i:;;£:^:t;t:i& &&:£:^;™^i?^?:^$$^ STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSH.P (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC •Z f"~l District Qg Building l~] Public Public Acquisition: 53 Occupied Yes: 0 i —i it .1 ["I Restricted Q Site CD Structure (XI Private D '" Process ( _| Unoccupied jj-.-j . —. _ . [yi Unrestricted CD Object D Botfl D Bein 9 Cons idered Q Preservation work W " h- in progress ' —' ^° U PREjSENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 1 1 Agricultural Q] Government | | Park ^(~1 Transportation , i | ED Comments i—i ^ L ••'' v- •'•••J.-J-'-V'' / .'X K] .Commercial CD Industrial f~| Private Residence 1 1 Other (Sbet-Jfvr ^ < / ,-^.\ 1- |~1 Educational CD Military [~[ Religious CD Entertainment CD Museum [~| Scientific 10 ...... ^m «, ,; ~, _7 • ' \ ._ ' z OWNER'S NAME: (- —— 1 fv ^' l '- ' ~ 1 STATE' Burlington Northern Inc. Nebraska UJ STREET AND NUMBER: UJ 1815 Capitol Plaza Building \%^. ° ^-^y^ en CJTY OR TOWN: STATE: ^Cl^J. ' PjJ> ^ODF . _, Omaha Nebraska 31 •3SSS::3&^ [in .;:S:S:SS:¥S:5;:;:5:;:i^i;::::S;:i:^^ COURTHOUSE, -

Tailspin Template

OMAHA NEBRASKA AMA 857 TAILSPIN NEWSLETTER April 2018 Issue President: Rick Miller Treasurer: Dean Copeland email: [email protected] Phone: 402-624-2530 email: [email protected] Address: 15668 Fountain Drive, Omaha 68118 Phone: 402-334-2787 Vice President: Rick Haneline Secretary: Tim Peters Phone: email: [email protected] Phone: 402-880-1508 email: [email protected] Tailspin Editor: Nelson Carpenter Phone: 402-709-3651 email: [email protected] A Word from the President Next Meeting: TBD How about this weather that we’ve been getting lately? If you are like me, you’re getting the itch to be out at the field flying. Are your winter projects done? If we’re lucky, the spring thaw won’t amount to much. Meaning the runway will not end up being water logged from snowmelt, and be free of rutting. Be sure to keep that in mind when driving out to the field. Including the pit area if you can avoid soft areas that could end up in deep ruts. Thanks! Note that our club no longer maintains its own website. Refer to Keith Paskewitz Metro RC website Vice-President’s Corner (http://www.metrorcflying.com) for current and back issues of Tailspin as well as club’s schedule of events. I've been out 3 or 4 times with an electric. It was nice to get in the air again. There is a nice video of my Valiant Your club dues can be sent in anytime now that we are being chased around at Hawk Field by an well into the New Year. -

REGISTER V O LU M E 33 • NUMBER 71 Thursday, April 11, 1968 ..• Washington, D.C

FEDERAL REGISTER V O LU M E 33 • NUMBER 71 Thursday, April 11, 1968 ..• Washington, D.C. Pages 5607-5653 Agencies in this issue— The President Agricultural Research Service Atomic Energy Commission Civil Aeronautics Board Civil Service Commission Consumer and Marketing Service Customs Bureau Federal Aviation Administration Federal Highway Administration Federal Maritime Commission Federal Power Commission Fish and Wildlife Service Food and Drug Administration Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau National Park Service National Transportation Safety Board Patent Office Post Office Department Securities and Exchange Commission State Department Detailed list o f Contents appears inside. Jüst Released CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS (As of January 1, 1968) Title 7—Agriculture (Parts 1060-1089) (Revised)____ $1. 00 Title 22— Foreign Relations (Revised)_________________ 1.25 Title 24—Housing and Housing Credit (Revised)______ 1.25 [A. cumulative chechlist of CFR issuances for 1968 appears in the first issue of the Federal Register each month under Title 1 ] Order from Superintendent of Documents, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on Sundays, Mondays, or on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Register, National FEDEML®REGISTERArchives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mail address National Area Code 202 »34 Phone 962-8626 <4VITEO’ Archives Building, Washington, D.C. 20408), pursuant to the authority contained in the Federal Register Act, approved July 26, 1936 (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.C., Ch. 8B ), under regulations prescribed by the Admin istrative Committee of the Federal Register, approved by the President (1 CFR Ch. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 ^ \Q-' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Burlington Station (AD04-1) AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER First St. & St. JosephT s Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Hastings _ VICINITY OF Third STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Nebraska 31 Adams 001 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM XBUILDING(S) 3LPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL X-TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Burlington Northern Railroad STREET & NUMBER 176 E. 5th CITY. TOWN STATE St. Paul, VICINITY OF Minnesota LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Adams County Courthouse STREETS. NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Hastings, Nebraska REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONIDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED JCORIGINALSITE ^GOOD —RUINS MOVER DATF —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Hastings Burlington Station is situated on First Street where St. Joseph's.Avenue meets the Burlington tracks from the north. The station terminates the vista of St. Joesph's Avenue at this point (see photo #2)., one block south of Second Street, Hastings 1 main business street. The Victory Building (Dutton-Lainson), a major Hastings land mark, stands at the corner of St.