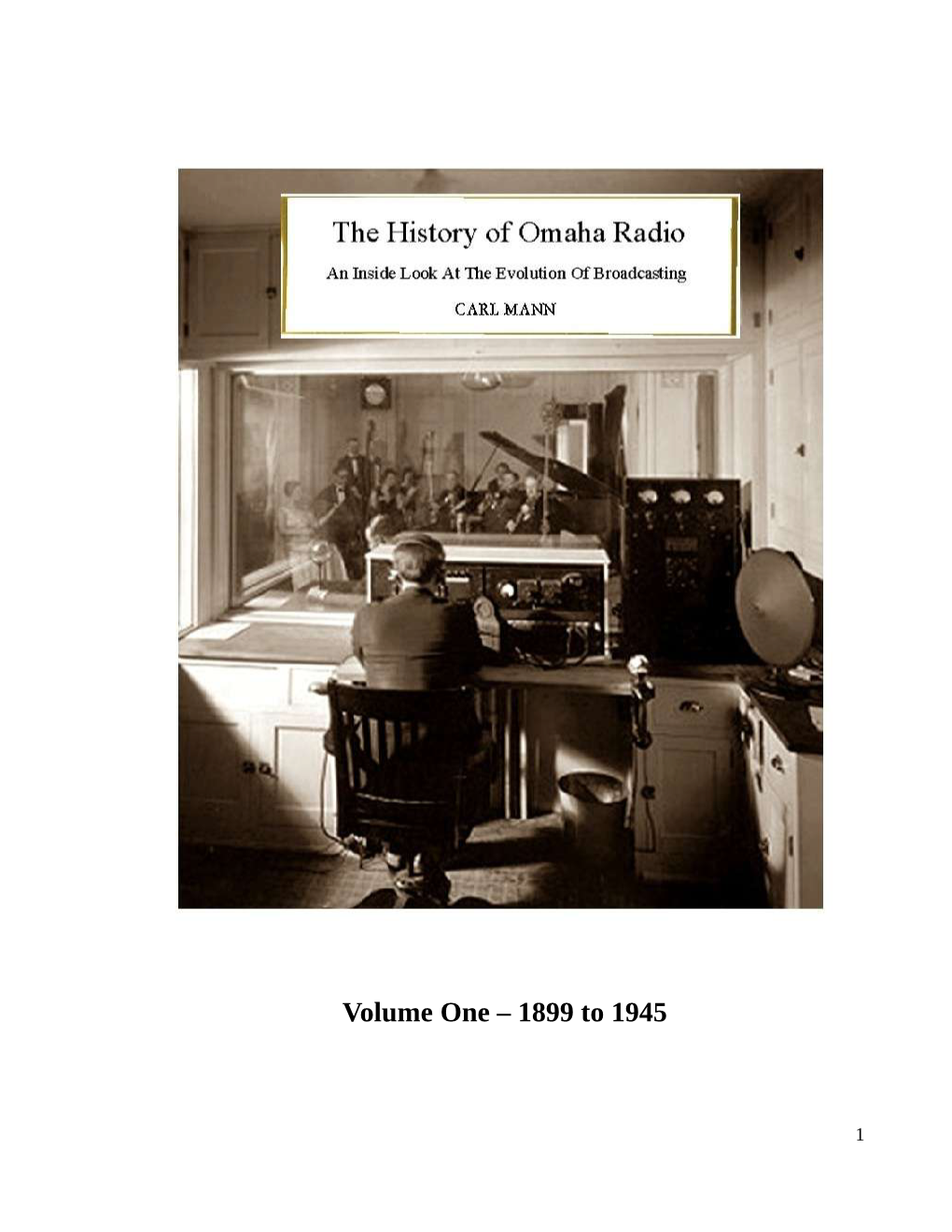

History-Of-Omaha-Rad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Resources at History Nebraska

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCES AT HISTORY NEBRASKA History Nebraska 1500 R Street Lincoln, NE 68510 Tel: (402) 471-4751 Fax: (402) 471-8922 Internet: https://history.nebraska.gov/ E-mail: [email protected] ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS RG5440: ADAMS-DOUGLASS-VANDERZEE-MCWILLIAMS FAMILIES. Papers relating to Alice Cox Adams, former slave and adopted sister of Frederick Douglass, and to her descendants: the Adams, McWilliams and related families. Includes correspondence between Alice Adams and Frederick Douglass [copies only]; Alice's autobiographical writings; family correspondence and photographs, reminiscences, genealogies, general family history materials, and clippings. The collection also contains a significant collection of the writings of Ruth Elizabeth Vanderzee McWilliams, and Vanderzee family materials. That the Vanderzees were talented and artistic people is well demonstrated by the collected prose, poetry, music, and artwork of various family members. RG2301: AFRICAN AMERICANS. A collection of miscellaneous photographs of and relating to African Americans in Nebraska. [photographs only] RG4250: AMARANTHUS GRAND CHAPTER OF NEBRASKA EASTERN STAR (OMAHA, NEB.). The Order of the Eastern Star (OES) is the women's auxiliary of the Order of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. Founded on Oct. 15, 1921, the Amaranthus Grand Chapter is affiliated particularly with Prince Hall Masonry, the African American arm of Freemasonry, and has judicial, legislative and executive power over subordinate chapters in Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, Grand Island, Alliance and South Sioux City. The collection consists of both Grand Chapter records and subordinate chapter records. The Grand Chapter materials include correspondence, financial records, minutes, annual addresses, organizational histories, constitutions and bylaws, and transcripts of oral history interviews with five Chapter members. -

Fort Omaha Balloon School: Its Role in World War I

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Fort Omaha Balloon School: Its Role in World War I Full Citation: Inez Whitehead, "Fort Omaha Balloon School: Its Role in World War I," Nebraska History 69 (1988): 2-10. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1988BalloonSchool.pdf Date: 7/30/2013 Article Summary: The captive balloon, used as an observation post, gave its World War I handlers a unique position among veterans. Fort Omaha became the nation's center for war balloon training, home to the Fort Omaha Balloon School. Cataloging Information: Names: Henry B Hersey, Craig S Herbert, Charles L Hayward, Frank Goodall, Earle Reynolds, Dorothy Devereux Dustin, Milton Darling, Mrs Luther Kountze, Daniel Carlquist, Charles Brown, Alvin A Underhill, Brige M Clark, Ralph S Dodd, George C Carroll, Harlow P Neibling, H A Toulmin, Charles DeForrest Chandler, John A Paegelow, Jacob W S Wuest, -

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885 (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Ray H. Mattison, “The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885,” Nebraska History 35 (1954): 17-43 Article Summary: Frontier garrisons played a significant role in the development of the West even though their military effectiveness has been questioned. The author describes daily life on the posts, which provided protection to the emigrants heading west and kept the roads open. Note: A list of military posts in the Northern Plains follows the article. Cataloging Information: Photographs / Images: map of Army posts in the Northern Plains states, 1860-1895; Fort Laramie c. 1884; Fort Totten, Dakota Territory, c. 1867 THE ARMY POST ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS, 1865-1885 BY RAY H. MATTISON HE opening of the Oregon Trail, together with the dis covery of gold in California and the cession of the TMexican Territory to the United States in 1848, re sulted in a great migration to the trans-Mississippi West. As a result, a new line of military posts was needed to guard the emigrant and supply trains as well as to furnish protection for the Overland Mail and the new settlements.1 The wiping out of Lt. -

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well PHYLLIS KEATY FOR JUDGE Report Number: 21630 Judge Third Circuit Court of Appeal CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE Lafayette Date Filed: 12/13/2010 P O Box 51951 109 S College Rd Report Includes Schedules: Lafayette, LA 70505 Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule B Schedule C 3. Date of Primary 11/2/2010 Schedule E-1 Schedule E-2 This report covers from 10/14/2010 through 12/2/2010 4. Type of Report: X 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more KIMBERLY NAQUIN banks, savings and loan associations, or money 350 Doucet Rd market mutual fund as the depository of all Suite 101 Lafayette, LA 70503 PAYPAL 2211 North First St San Jose, CA 95131 9. Name of Person Preparing Report MARK P HARRIS CPA; APAC Daytime Telephone 337-235-2002 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. -

Qpieeii , * Lack Tiac — Admission — Band’S of Interest

1 CO-STARRED A DRAMATIC MOMENT CUR-A-A-Z-Y FOR BLONDES ! ■■ ..————— CURRENT FILM _ '•'■'SBPifc___ BANDIT TYPE Btttmann AT CAPITOL IS DODGED BY Today — 3 Day* PRIZE DRAMA JAMES CAGNEY “Street Scene,” picturized from Janies Cagney, who is co-fea- the famous Pulitzer Prize play by tured with Joan Blonde 11 in "Blonde Elmer Rice, is presented by Samuel! Crazy," the Warner Bros, Goidwyn at the Capitol theatre to- produc- tion now at the Riroli San day and tomorrow. In directing > theatre. the story oi u. warm-hearted ro- Benito—after his tremendous suc- mance and a passionate murder cess in “The Public Enemy'* faced against the screen of a living city the danger of becoming typed in street. King Vidor makes of "Street future screen & Scene” his most ambitious effort appearances as since “The Big Parade.*’ gangster. Sylvia Sidney in whose ears are The bit which lie did in support still ringing the nation-wide acclaim j of George Arliss in “The Million- that greeted her appearance in "An :f MAURICE aire" conclusively proved his talent American Tragedy has the roman- for comedy. Scenes like the one CHEVALIER tic lead in the picture. William Col- f with Ma Delano, his mother, in I in AN ERNST lier, Jr., plays opposite her. Estelle "Sinners’ Holiday" displayed the Taylor follows her brilliant per- Evalyn Knapp. James Cagney and Joan Blondell In a scene from LUBITSCH j tragic depths which he car. reach. action formance in "Cimarron" with the -Blonde Crary ’, showing Sunday and Monday at the Rivoli Prod theatre, In "Blonde Cra/v” he plays the exacting and difficult role of Mrs. -

High Powered History the History of VOA Bethany

The Broadcasters’ Desktop Resource www.theBDR.net … edited by Barry Mishkind – the Eclectic Engineer High Powered History The History of VOA Bethany By Clyde G. Haehnle [February 2011] Just down the road from WLW was another transmission site with a history that con- tinues to be of interest 60 years after its construction. Clyde Haehnle was among those who built and worked at a site that became known the world over. Adolph Hitler called us “The Cincinnati Liars.” It was a badge of honor we relished as we pumped out over 1.5 Megawatts of RF from a plant in Ohio, purposely built to project American news and views around the world. They were needed. Prior to December 7, 1941 Germany had 68 shortwave transmitters operating on the air, Japan had 42. The United States had but 13. And while Germany and Japan dedicated their facilities to psychological warfare, none of the U.S. transmitters were used for propaganda. The US was ill-equipped to effectively counteract this barrage. At that time the most powerful shortwave transmitter available to the United States was WLWO. Cros- ley Broadcasting operated WLWO’s 75 kW composite shortwave transmitter next to WLW at Mason, OH, broadcasting to South America and Europe. WLWO’s antenna system included two small reentrant rhombic antennas, one aimed at Western South America and one toward Europe. TURNING ATTENTION TO SHORTWAVE In January of 1942 the Coordinator of International Affairs, requested WLW engineers to acquire another shortwave transmitter and design and construct four larger and more efficient antennas to better serve Europe and South America. -

Kern Community Radio

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Amendment of Section 73.3556 of the ) MB Docket No. 19-310 Commission’s Rules Regarding Duplication of ) Programming on Commonly Owned Radio Stations ) ) Modernization of Media Regulation ) MB Docket No. 17-105 Initiative ) Reply Comments of Kern Community Radio This reply comment is from nonprofit Kern Community Radio (“Kern”). Kern is a prospective non-commercial community broadcaster in Bakersfield, California. Kern is supplying this comment to shed light on the reality of how duplicated- and rebroadcast- programming is an epidemic. Redundant and relayed programming is hollowing-out local radio, vastly reducing programming diversity, and frustrating diverse new broadcast entrants. This reply is being filed as a response to National Association of Broadcasters’ (“NAB”) comment stating that diversity has increased on the dail, advocating the lift of the duplication rule. Kern provides proof in this reply that the program duplication rules need to be expanded to ensure local programming diversity and allow for new entrants. About Kern Community Radio Members of Kern Community Radio had desired to pursue a non-commercial, educational community radio station for Bakersfield in 2006 due to the total absence of any local local secular non-commercial radio. Bakersfield, a metropolitan area of roughly 840,000 people, does not have one local-studio secular, non-commercial radio station. That includes no secular LPFM, no local-content NPR station,1 no community station, or no college station. The entire non-commercial FM band except for one station is all relayed via satellite from chiefly religious broadcasters from Texas, Idaho, and Northern California. -

KCRO, KOBM-AM,KOBM-FM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2019 - February 1, 2020

Page: 1/6 KCRO, KOBM-AM,KOBM-FM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2019 - February 1, 2020 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Sales and Marketing Consultant 1-25 19 Sales and Marketing Consultant 1-25 19 Page: 2/6 KCRO, KOBM-AM,KOBM-FM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2019 - February 1, 2020 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period Bellevue University 1000 Galvin Rd South Bellevue, Nebraska 68005 1 Phone : 402 557-7423 N 0 Email : [email protected] Fax : 1-402-557-5438 Colleen Plasek Broadcast Media Placement 147 Andersen Hall Lincoln, Nebraska 68588 2 Phone : 402 472-3054 N 0 Email : [email protected] Fax : 1-402-472-8403 Rick Alloway College of St Mary 7000 Mercy Road Omaha, Nebraska 68106 3 Phone : 402 399-2366 N 0 Email : [email protected] Angela Fernandez Envoy 6901 Pacific St #102 Omaha, Nebraska 68106 4 Phone : 402 558-0637 N 0 Email : [email protected] Fax : 1-402-558-0972 Brooke Ortner 5 Indeed.com N 1 Metropolitan Community College 835 N Broad St Fremont, Nebraska 68025 6 Phone : 402 721-2507 N 0 Email : [email protected] Todd Hansen Midland University 900 North Clarkson Fremont, Nebraska 68025 7 Phone : 402 941-6471 N 0 Email : [email protected] Connie Bottger Page: 3/6 KCRO, KOBM-AM,KOBM-FM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2019 - February 1, 2020 II. -

A Thesis Presented to by Margaret Eller Mcwethy July 1954 In

A Study of student radio broadcasting as a motivation in speech improvement Item Type Thesis Authors McWethy, Margaret Eller Download date 05/10/2021 17:16:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/4998 A STUDY OF STUDENT RADIO BROADCASTING AS A MOTIVATION IN SPEECH IMPROVEMENT A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Education Indiana State Teachers College Terre Haute, Indiana In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Education " J).j ,J :' , J)' ).' ,'.. , :> '):;.,:> ):l:) " .• ,.., '., -" , J , J;' ,-, J ,J -, , , "j, , "" ) " " ,'.J' : ;::' :: ~ ,\. ~:: A"~ " , , " ')', .J,' J .' ,, 'J., • " J' 'J ~ -' " ). iI , by Margaret Eller McWethy July 1954 The thesis of Margaret Eller McWethy Contribution of the Graduate School, Indiana State Teachers College, Number 753 ,under the title------ A Study of Student Radio Broad9asting as a Motivation in Speech Improvement is hereby approved as counting toward the completion of the Master's degree in the amount of hours' credit. chairman Date of Acceptance --,---,- ~ _ TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITIONS OF TERMS USED o • • • I Introduction . ...•.•. .. .. I The problem ••.......• · .. 2 Statement of the problem" •. .. 2 Importance of the study •.. ·. 2 Definitions of terms used .•.. 3 WPRS .... · . 3 'Broadcasting . •..•.. ...... •• 4 Live program ..••...•• 4 Tape recording .•...•. 4 Remote pick-up .•.•...••••. 5 Mike .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. • · . 5 Level .. ..• 5 Off mike . •.•. .. .. 5 Fade •.. 5 Fade in and fade off . ~ ..••. 6 Ad lib. • .•• -6 Script •.••.••..•• 6 Limitations of the study .•...•.•.• 6 Organization of the remainder of the study ••• 7 II. A REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE .. ...•• 8 III •. OBJECTIVES OF STUDENT BROADCASTING. • •• 10 iii CHAPTER PAGE IV. THE PREPARATION OF HIGH SCHOOL RADIO PROGRAMS 13 Clinton High School's approach to the problem 13 Types of programs . -

Extensions of Remarks E559 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

April 26, 2013 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E559 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS RECOGNIZING HIGH SCHOOL RADIO young students eager to learn the ways of ity and has made Qatar a beacon of higher DAY broadcast journalism. education in the region and around the world. Mr. Speaker, at this time, I ask that you and f HON. PETER J. VISCLOSKY my distinguished colleagues join me in recog- nizing these two exemplary student organiza- RESPONSIBLE HELIUM ADMINIS- OF INDIANA tions, as well as each of the 43 high school TRATION AND STEWARDSHIP IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES radio stations from 19 States participating in ACT Friday, April 26, 2013 High School Radio Day 2013. Their efforts Mr. VISCLOSKY. Mr. Speaker, it is with have molded and continue to mold genera- SPEECH OF great pride and sincerity that I rise in recogni- tions of rising journalists, performing a vital HON. MICHAEL M. HONDA tion of High School Radio Day 2013. This year public service for all Americans. OF CALIFORNIA marks the second annual High School Radio f Day, a day to observe the uniqueness of each IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES high school radio station and the impact each HONORING THE STATE OF QATAR Thursday, April 25, 2013 has on the community, the State, and the Na- AND HIS HIGHNESS SHEIKH, HAMAD BIN KHALIFAH AL-THANI The House in Committee of the Whole tion at large. Indiana is the birthplace of high House on the state of the Union had under school radio. The first station in the United consideration the bill (H.R. -

Bakersfield, CA (Cant.)

THE EXLINECOMPANY MEDIA BROKERS - CONSI!LT.ANTS p February 9,7004 Alfrcdo Plascenaa President I~.azerBroadcasting Corporation 200 South A Street, Suite 400 Oxnard, CA 93030-5717 Dear MI-. Plascencia, Herewith. in narrative forrri, is the review and appnisal of all of the assets, whicli are used and usable in the operatlons of five Radio Slations KAhX-FM, AveIial, KAJP-FM, Firebaugh, KZPE-FM, Ford City, KZPO-FM, Lindsay, and KNCS-FM. Coalinga, all California. I have not personally vislted the subject propernes, have no past 11oI coiiternplale furure interest in them and I have made the necessary investigation and analyses to develop this review and appralsal, subjcct only to the limitations heremafter described. The value determined rhrough this process is that of July 2003. ST-ATEMENT OF PURPOSE AND VALUE The purpose of this appraisal is to estiiiiattr the fair markel value of the aforementioned assets. The assets consisr of leases md personal property wi'th attendant licenses and pcrmits, which provide for the daily operation of the sublect ststioiir serving !he central San Joaquin Valley area of Californian horn FirebaLld7~ iii the north to Ford City in the south (Map enclosed.) This appraisal has been prepared at the specific direction of Mr. Alfred0 Plasceniia. President, Lazer Broadcasting Corporation. Marliet value is defined as the ‘‘hghesf price estimated in terms ofmoiley which a proprny will bring if exposed for sale tn the open market, allowing a reasonable ninc to t-md ;1 purchaser who buys with howledge of all of the uses to which it IS adapted arid for which it is capable of being used.’’ IDENTIFICATION OF FACLLLITIES Ktt9X-FM is a local class A station with 6 ku. -

A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2018-07-01 El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wilkins, Rex Richard, "El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk in Spain and Mexico" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 6997. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6997 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Brian Price, Chair Erik Larson Alvin Sherman Department of Spanish and Portuguese Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Rex Richard Wilkins All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT El futuro ya está aquí: A Comparative Analysis of Punk Culture in Spain and Mexico Rex Richard Wilkins Department of Spanish and Portuguese, BYU Master of Arts This thesis examines the punk genre’s evolution into commercial mainstream music in Spain and Mexico. It looks at how this evolution altered both the aesthetic and gesture of the genre. This evolution can be seen by examining four bands that followed similar musical and commercial trajectories.